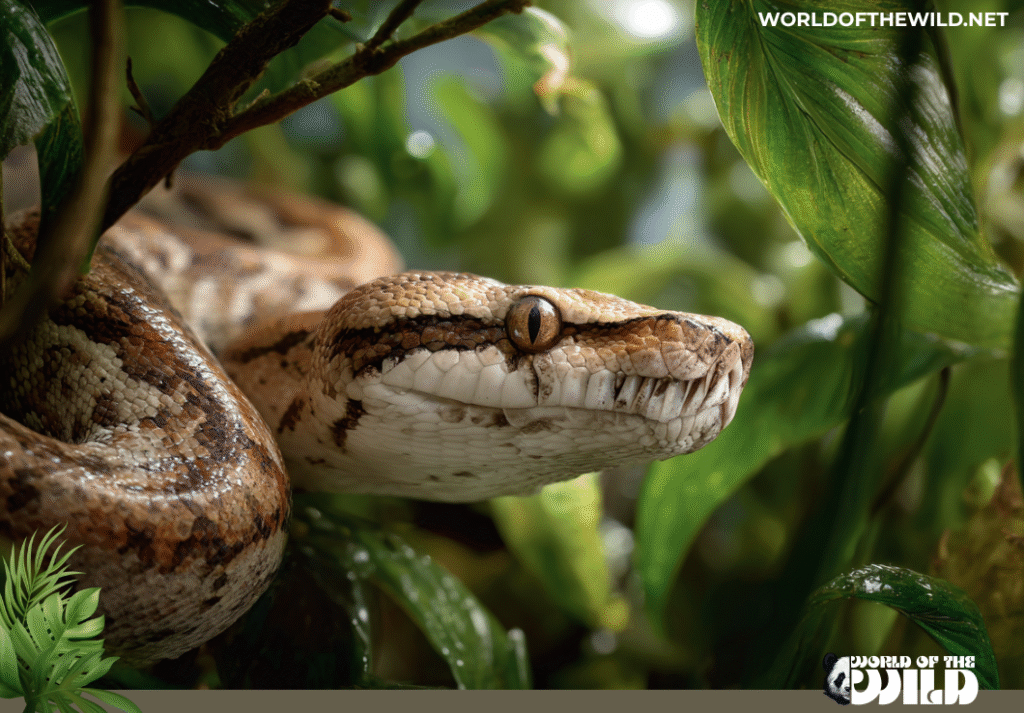

High in the emerald labyrinth of South America’s rainforests, a serpent coils around a moss-draped branch, its body perfectly camouflaged among the dappled shadows and tropical foliage. The Amazon Tree Boa is a creature of remarkable elegance and adaptability, a predator that has transformed the forest canopy into its personal hunting ground. Unlike its larger, more famous cousin the anaconda, this slender arboreal snake represents one of nature’s most successful experiments in vertical living. What makes this reptile truly fascinating is not just its stunning color variations—from vivid orange to deep charcoal—but its complete mastery of three-dimensional space in one of Earth’s most complex ecosystems. In a world where most boas are associated with the forest floor, the Amazon Tree Boa has written its own evolutionary story in the branches above.

Facts

- Color-Changing Chameleons: Amazon Tree Boas undergo dramatic color shifts between day and night, with many individuals appearing significantly darker during daylight hours and lighter at night—a phenomenon thought to aid in thermoregulation.

- Heat-Seeking Missiles: These serpents possess specialized heat-sensing pits along their jaw line that allow them to detect the infrared radiation from warm-blooded prey, making them deadly accurate hunters even in complete darkness.

- Athletic Strikers: Unlike many ambush predators, Amazon Tree Boas can strike across remarkable distances—sometimes launching nearly half their body length through the air to snatch birds and bats in mid-flight.

- Living Anchors: Their prehensile tail functions as a fifth limb, capable of supporting the snake’s entire body weight while it hangs suspended to reach prey or traverse between branches.

- Baby Giants: Newborn Amazon Tree Boas are surprisingly large compared to their parents, often measuring 15-20 inches at birth—a size that allows them to immediately hunt substantial prey.

- Polymorphic Populations: Within a single geographic area, Amazon Tree Boas can display an astounding array of color morphs, from brilliant reds and oranges to yellows, grays, and browns, with scientists still debating the evolutionary advantages of this variety.

- Jaw-Dropping Flexibility: Their highly kinetic skulls feature loosely connected jaw bones that can separate widely, allowing them to consume prey nearly as thick as their own body diameter.

Species

The Amazon Tree Boa belongs to a taxonomic classification that places it firmly within the constrictor family:

Kingdom: Animalia

Phylum: Chordata

Class: Reptilia

Order: Squamata

Family: Boidae

Genus: Corallus

Species: Corallus hortulanus

The genus Corallus contains several closely related arboreal boa species, all adapted for life in the trees of Central and South America. The most notable relatives include the Emerald Tree Boa (Corallus caninus), famous for its brilliant green coloration and striking white markings, and the Annulated Tree Boa (Corallus annulatus), found in Central America and parts of northern South America. While the Amazon Tree Boa was once considered to have several subspecies, modern molecular analysis suggests Corallus hortulanus may actually represent a complex of several cryptic species that are nearly identical in appearance but genetically distinct. The Cook’s Tree Boa (Corallus cookii) and the Cropan’s Boa (Corallus cropanii), both from Brazil’s Atlantic Forest, were once lumped with the Amazon Tree Boa but are now recognized as separate species. This taxonomic complexity reflects the vast distribution and environmental diversity across the Amazon Tree Boa’s range, where isolated populations have developed subtle but significant differences over millennia.

Appearance

The Amazon Tree Boa is a study in graceful proportion and chromatic diversity. Adults typically measure between 5 to 7 feet in length, with females generally outgrowing males—a common pattern in snakes known as sexual size dimorphism. Despite their impressive length, these are remarkably slender serpents, rarely exceeding 2 inches in diameter at their thickest point. Their weight reflects this lean build, with most adults ranging from 2 to 3 pounds, though particularly robust females may approach 4 pounds.

What truly sets this species apart is its bewildering array of color variations. Individual Amazon Tree Boas can be found in shades of orange, red, yellow, brown, gray, olive, or nearly black, often adorned with darker blotches, diamonds, or irregular patterns along their backs and sides. Some populations in Suriname are famous for producing stunning “garden phase” morphs with vibrant orange or red-orange coloration, while others display more cryptic earth tones. This variation isn’t simply regional—wildly different colors can appear within the same locality, even among siblings.

The head is distinctly wider than the neck, with a relatively narrow, elongated profile when viewed from above. The eyes are large and prominent with vertical, elliptical pupils—the hallmark of a nocturnal hunter. Along the upper and lower jaws, subtle labial pits create small indentations; these are the snake’s thermal sensors, appearing as small dark holes between the scales. The body scales are smooth and glossy, giving the snake an almost polished appearance, while the ventral scales (belly scales) are relatively narrow compared to terrestrial species, an adaptation for arboreal life. The tail is notably long and muscular, tapering to a fine point, perfectly engineered for gripping branches with precision. When coiled at rest, the Amazon Tree Boa arranges its body in a series of parallel, horseshoe-shaped loops draped over branches—a characteristic resting posture that distinguishes tree boas from other arboreal snakes.

Behavior

The Amazon Tree Boa is predominantly nocturnal, spending daylight hours coiled motionless on branches or tucked into tree hollows, where its coloration provides exceptional camouflage against bark and foliage. As darkness falls, these serpents become active hunters, slowly traversing the canopy network with deliberate, fluid movements. They navigate their three-dimensional world with remarkable spatial awareness, using their prehensile tail as both anchor and rudder.

These are solitary creatures outside of breeding season, maintaining territories within their vertical domains. Communication is limited and primarily chemical; like most snakes, they use their forked tongues to sample airborne particles, drawing them back to the Jacobson’s organ in the roof of their mouth to detect prey, predators, and potential mates. During breeding season, females may release pheromones that males can detect across considerable distances.

Amazon Tree Boas are ambush predators with extraordinary patience. A hunting individual will position itself strategically along a branch or vine, often near gaps in the canopy where birds and bats travel, and remain absolutely motionless for hours. Their heat-sensing pits allow them to create a thermal map of their surroundings, detecting the subtle warmth of approaching prey long before visual contact. When opportunity arrives, the strike is explosive—a lightning-fast lunge that can intercept a flying bat in mid-air or snatch a roosting bird before it registers danger.

One of their most remarkable adaptations is their ability to bridge significant gaps between trees. By anchoring their tail securely and extending their body outward, they can span distances that seem impossibly far, effectively fishing through empty air for the next handhold. This arboreal agility is complemented by an unexpected defensive behavior: when threatened, Amazon Tree Boas are quick to bite and can be surprisingly aggressive. Unlike many snakes that rely primarily on bluff displays, these boas will readily defend themselves with repeated strikes, though their bites, while painful, are not venomous.

Young Amazon Tree Boas display different behavior than adults, often hunting during daylight hours and targeting smaller prey like lizards and tree frogs. As they mature, they gradually shift to nocturnal habits and larger prey items. The species shows considerable learning ability, with individuals in human care quickly recognizing feeding schedules and even individual caretakers, suggesting a level of cognitive sophistication often underestimated in reptiles.

Evolution

The evolutionary history of the Amazon Tree Boa is written in the ancient emergence of the boa family and the specialized adaptations that allowed certain lineages to conquer the rainforest canopy. The family Boidae has roots stretching back to the Cretaceous period, over 70 million years ago, when snakes themselves were relatively young as a group. Fossil evidence suggests that early boas were terrestrial and semi-aquatic, inhabiting the supercontinent of Gondwana before its fragmentation.

The genus Corallus, to which the Amazon Tree Boa belongs, represents a more recent evolutionary innovation—the transition to arboreal life. This shift likely occurred during the Cenozoic era as South America’s tropical forests expanded and diversified. The development of the prehensile tail, enlarged eyes for nocturnal vision, heat-sensing labial pits, and a slender body profile all represent key evolutionary adaptations that allowed these boas to exploit the rich prey resources available in the forest canopy, particularly the abundance of roosting birds and fruit bats.

Molecular clock analyses suggest that the Corallus lineage diverged from other boa groups perhaps 30-40 million years ago, during a period of significant ecological diversification in Neotropical forests. The remarkable color polymorphism seen in Corallus hortulanus populations presents an evolutionary puzzle that scientists continue to investigate. Unlike the adaptive coloration seen in many species where color matches specific habitats, Amazon Tree Boas display multiple color morphs within the same environment, suggesting that this variation may relate to other factors such as thermoregulation, individual camouflage strategies across different microhabitats, or perhaps even predator confusion.

The species’ closest evolutionary relative appears to be the Emerald Tree Boa (Corallus caninus), which shares the arboreal lifestyle but has evolved the distinctive bright green coloration common in many canopy dwellers. Interestingly, the Emerald Tree Boa and the Green Tree Python of Australia represent a striking example of convergent evolution—unrelated snakes that independently evolved nearly identical body forms and behaviors for life in tropical trees, demonstrating that the arboreal niche consistently favors certain physical solutions.

Habitat

The Amazon Tree Boa ranges across a vast expanse of northern South America, including the Amazon Basin and surrounding regions. Its distribution encompasses countries including Brazil, Venezuela, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, Bolivia, Guyana, Suriname, French Guiana, and Trinidad and Tobago. This extensive range reflects the snake’s adaptability to various forested environments, though it shows a strong preference for areas with dense canopy coverage.

Within this broad geographic range, Amazon Tree Boas inhabit primarily tropical and subtropical rainforests, where they occupy the lower to mid-canopy layers, typically between 6 to 50 feet above the ground. They show particular affinity for areas near water sources—riverbanks, streams, and seasonally flooded forests—where prey concentrations are highest. The snakes are equally at home in primary old-growth rainforest and secondary growth forests, as long as sufficient tree cover exists.

The specific microhabitats they select reveal their precise ecological requirements. Amazon Tree Boas favor areas with dense vine tangles, clusters of bromeliads and other epiphytes, and networks of horizontal and diagonal branches that create three-dimensional travel corridors. These structural features provide not only hunting perches but also refuges from their own predators and shelter from the elements. During the day, they often coil in tree hollows, beneath bark, or among thick vegetation where dappled light and shadow enhance their camouflage.

The species demonstrates tolerance for habitat edges and disturbed forests better than many rainforest specialists, occasionally appearing in plantations, gardens, and rural areas adjacent to forest fragments, though these represent marginal habitats. In some parts of their range, particularly in the Guianas, they’ve been documented in flooded forests and mangrove swamps, showcasing their ecological flexibility.

Temperature and humidity are critical factors. Amazon Tree Boas thrive in environments where temperatures remain relatively stable between 75-85°F, with humidity levels consistently above 60%. The rainforest canopy provides this stable microclimate, buffering against the temperature extremes that would stress these cold-blooded reptiles. During seasonal dry periods, they may descend closer to ground level or seek areas near water where humidity remains higher.

Diet

The Amazon Tree Boa is a dedicated carnivore, specializing in warm-blooded prey that inhabits or passes through the forest canopy. Their diet consists primarily of birds, bats, and small mammals, though juveniles also consume lizards and tree frogs until they grow large enough to tackle more substantial quarry.

Birds represent a significant portion of the adult diet, including species that roost, nest, or forage in the trees. They’re opportunistic hunters, taking whatever avian prey presents itself—from tanagers and parrots to doves and nightjars. Their heat-sensing abilities and nocturnal habits make them particularly effective at locating roosting birds in complete darkness, detecting the subtle warmth radiating from a sleeping songbird tucked beneath its wing.

Bats, however, may be their most important prey item in many ecosystems. The Amazon Basin hosts spectacular bat diversity, and these flying mammals represent concentrated protein sources that Amazon Tree Boas have become expert at exploiting. Using their thermal sensors, the snakes can detect bats returning to roosts or commuting through regular flight corridors. Some individuals position themselves near cave entrances or hollow trees where bat colonies emerge at dusk, striking at the stream of animals as they exit.

Small mammals round out the diet, including rodents, opossums, and occasionally young primates when opportunity allows. Tree-dwelling rodents like spiny rats and climbing mice are particularly vulnerable, as they share the snake’s arboreal realm.

The hunting strategy relies on stealth and the element of surprise. Amazon Tree Boas are constrictors, meaning they kill by wrapping coils around their prey and tightening until the victim suffocates from the pressure preventing inhalation. Contrary to popular myth, they don’t crush bones but rather create a python-like grip that prevents the chest from expanding. The process is remarkably efficient; prey typically loses consciousness within seconds and dies within minutes. The snake’s heat pits allow it to monitor the prey’s declining body temperature, confirming death before beginning the lengthy process of swallowing the animal whole.

Digestion is a slow, energy-intensive process. After consuming a meal—which may weigh 25% or more of the snake’s own body weight—an Amazon Tree Boa will seek a secure perch and remain largely immobile for days or even weeks while digestive enzymes break down the prey. During this vulnerable period, they’re less responsive and more exposed to predation, which is why they’re particularly selective about post-feeding refuges.

Feeding frequency varies with prey availability, temperature, and the individual snake’s condition. A healthy adult might feed every 10-14 days during peak activity seasons, though they can survive months without food if necessary—a common adaptation in environments where prey availability fluctuates.

Predators and Threats

Despite their position as effective predators, Amazon Tree Boas face threats from multiple sources throughout their lives. Natural predators vary by the snake’s age and size, creating a shifting landscape of danger as they mature.

Juvenile Amazon Tree Boas, measuring under 2 feet in length, are vulnerable to a wide array of predators. Large spiders, tree-dwelling snakes including other Corallus species, predatory birds such as hawks, falcons, and the Harpy Eagle, opossums, tayras, coatis, and even large tree frogs may prey upon young boas. Their small size and developing hunting skills make these early years particularly perilous, with mortality rates highest during the first year of life.

As they grow, the list of potential predators narrows but never disappears entirely. Adult Amazon Tree Boas still face threats from larger raptors, particularly the formidable Harpy Eagle, which specializes in canopy prey and possesses the strength to kill even sizeable snakes. Large cats including ocelots, margays, and occasionally jaguars will consume tree boas when encountered, though these snakes are not primary targets. Perhaps surprisingly, other snakes pose threats too—larger boa species and the venomous Bushmaster have been documented consuming tree boas.

Human-caused threats represent an escalating challenge that overshadows natural predation. Habitat destruction stands as the primary anthropogenic threat, with deforestation rates in the Amazon Basin reaching alarming levels. Logging, agricultural expansion for cattle ranching and soy production, mining operations, and infrastructure development fragment and eliminate the continuous forest canopy that Amazon Tree Boas require. Unlike ground-dwelling species that might traverse gaps between forest patches, arboreal specialists struggle when trees are removed, effectively isolating populations.

The international pet trade creates additional pressure on wild populations. Amazon Tree Boas, particularly the vibrant color morphs, are sought after by reptile enthusiasts. While captive breeding programs now produce many specimens for the pet market, wild collection continues in some areas, with smugglers targeting particularly colorful individuals. This selective pressure could theoretically alter the genetic diversity of wild populations over time.

Climate change introduces new, less quantifiable threats. Altered rainfall patterns, increased drought frequency, and temperature shifts affect both the snakes directly and the prey populations they depend upon. More frequent and intense forest fires, often started by humans but exacerbated by climate-driven drought, destroy habitat and kill snakes that cannot escape the flames.

Local persecution by humans who fear or misunderstand snakes contributes to mortality, though this is less systematic than the threats above. Road mortality affects populations near human settlements, and pollution from agricultural runoff and mining operations degrades habitat quality in some regions.

Reproduction and Life Cycle

Amazon Tree Boas follow a reproductive pattern common among boas: they are ovoviviparous, meaning females retain eggs internally and give birth to live young rather than laying eggs. This reproductive strategy offers significant advantages in the arboreal environment, where finding safe incubation sites for eggs would be challenging.

The breeding season typically occurs during the cooler, drier months, varying by geographic location but generally falling between May and August in much of their range. Males become more active during this period, traveling greater distances through the canopy in search of receptive females. When a male detects a female’s pheromone trail, he follows it with determined persistence, sometimes traveling for several nights to locate her.

Courtship is a prolonged affair involving tactile stimulation. The male crawls along the female’s body, flicking his tongue constantly to assess her readiness, while using his vestigial spurs—tiny remnants of hind legs found in all boas—to scratch and stimulate her sides. If receptive, the female will allow the male to align his tail with hers, and copulation may last several hours. A female may mate with multiple males during a single breeding season.

Following successful mating, the female’s body undergoes dramatic changes. The gestation period lasts approximately 5 to 7 months, during which she becomes noticeably thicker as the developing young grow within her. Pregnant females thermoregulate carefully, seeking warm perches during the day to optimize embryonic development, and they typically cease feeding during the latter stages of pregnancy.

Birth is a remarkable event. A typical litter contains 5 to 20 offspring, though clutches as large as 30 have been documented. The newborns emerge encased in transparent membranes which they immediately rupture, emerging as fully formed, miniature replicas of their parents. These neonates measure 15 to 20 inches in length—impressively large for newborn snakes—and are capable of independent survival from their first breath.

Parental care is nonexistent in this species. Once birth is complete, the female shows no further interest in her offspring, and the young immediately disperse into the surrounding vegetation. This lack of parental investment is compensated for by the advanced development of the neonates, who possess fully functional heat pits, hunting instincts, and constricting ability.

The early life of a juvenile Amazon Tree Boa is precarious. They shed their skin for the first time within days of birth, and must successfully hunt within their first few weeks or face starvation. Initial prey consists of small lizards, tree frogs, and occasionally nestling birds. Growth is relatively rapid in the first few years, with juveniles reaching 3 to 4 feet within their first two years under optimal conditions.

Sexual maturity arrives at different times for males and females. Males typically reach breeding condition at around 3 to 4 years of age, when they measure approximately 4 to 5 feet in length. Females mature later, generally at 4 to 5 years, needing to achieve the larger body size necessary to successfully carry developing young.

The lifespan of wild Amazon Tree Boas is difficult to determine precisely, as tracking individual snakes through dense rainforest canopy over decades presents obvious challenges. However, based on growth rates, sexual maturity timing, and observations of captive individuals, experts estimate wild specimens may live 12 to 20 years under favorable conditions. In captivity, where predation, disease, and food scarcity are eliminated, Amazon Tree Boas regularly reach 20 to 25 years, with exceptional individuals documented living beyond 30 years.

Population

The Amazon Tree Boa currently holds a conservation status of “Least Concern” according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), reflecting its wide distribution across northern South America and its presence in numerous protected areas. This designation suggests the species is not facing immediate extinction risk across its entire range.

However, this overall assessment masks considerable regional variation and emerging concerns. Estimating global population numbers for a cryptic, arboreal snake distributed across millions of square miles of dense rainforest presents enormous methodological challenges. No comprehensive population census exists, and scientists rely instead on encounter rates, habitat modeling, and extrapolation from studied populations to estimate overall numbers.

What data does exist suggests that Amazon Tree Boa populations remain relatively healthy in protected wilderness areas, particularly within large national parks and indigenous reserves where habitat remains intact. In these regions, encounter rates during targeted surveys indicate stable or potentially increasing populations, likely reflecting the snake’s adaptability and generalist prey preferences.

The picture darkens considerably in areas experiencing active deforestation and habitat fragmentation. Studies from the arc of deforestation along the southern and eastern Amazon Basin show declining encounter rates and local extirpations in heavily impacted regions. Forest fragments smaller than several hundred acres may not support viable populations long-term, as the species requires sufficient territory for hunting and genetic exchange with neighboring populations.

Population trends appear stable to slowly declining overall, driven by the relentless pressure of habitat loss. While the Amazon Tree Boa’s extensive range provides a buffer against total collapse, the species faces a death by a thousand cuts as deforestation chips away at continuous forest. Current deforestation rates in the Amazon, if sustained, could eliminate substantial portions of prime habitat within the coming decades.

Some populations face specific local threats. The garden phase color morphs in Suriname, prized for their brilliant coloration, experience targeted collection pressure. Certain island populations, particularly in Trinidad, represent genetically distinct groups with limited range, making them disproportionately vulnerable to localized threats.

Conservation efforts benefit the Amazon Tree Boa indirectly rather than through species-specific programs. The establishment and maintenance of protected areas, indigenous land rights recognition, sustainable forestry initiatives, and broader Amazon conservation campaigns all contribute to preserving the habitat matrix this species requires. International regulations restricting wildlife trade, including CITES appendix listings for related species, create framework for monitoring and regulating any commercial exploitation.

Climate change introduces uncertainty into all population projections. Shifts in rainfall patterns could alter prey availability, while increased fire frequency threatens to fragment habitat in new ways. The species’ broad distribution suggests some populations may prove resilient, but others, particularly those at range edges or in already stressed habitats, face an uncertain future.

Conclusion

The Amazon Tree Boa stands as a testament to evolution’s remarkable creativity, a serpent that abandoned the forest floor to master the complex three-dimensional world of the rainforest canopy. Through specialized adaptations—heat-sensing pits, prehensile tails, explosive striking ability, and bewildering color variation—this species has carved out a unique ecological niche as one of the canopy’s most efficient predators. Yet for all its evolutionary success, the Amazon Tree Boa’s fate remains tied to the larger story of rainforest conservation in an era of unprecedented habitat loss.

While currently not facing immediate extinction, this species serves as an indicator of broader ecosystem health. Its presence signals intact forest structure, abundant prey populations, and the complex ecological relationships that define healthy tropical ecosystems. As deforestation accelerates and climate change introduces new uncertainties, protecting the Amazon Tree Boa means protecting the magnificent forest cathedral it calls home. For those who care about biodiversity, the choice is clear: the preservation of mysterious, beautiful creatures like the Amazon Tree Boa depends on our collective commitment to halting deforestation, supporting indigenous land rights, and recognizing that these forests—and the countless species they harbor—represent irreplaceable treasures whose value transcends economic calculation. The tree boa asks nothing of us except the chance to continue its ancient existence in the branches where it belongs.

Scientific Name: Corallus hortulanus

Diet Type: Carnivore

Size: 5-7 feet (1.5-2.1 meters)

Weight: 2-4 pounds (0.9-1.8 kg)

Region Found: Northern South America (Amazon Basin, including Brazil, Venezuela, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, Bolivia, Guyana, Suriname, French Guiana, and Trinidad and Tobago)