In the quiet hum of a summer garden lies one of nature’s most extraordinary achievements: the honey bee. These tiny aviators, weighing less than a paperclip, are responsible for pollinating approximately one-third of the food we eat. From the almonds in your morning cereal to the apples in your lunchbox, honey bees work tirelessly behind the scenes, orchestrating an intricate dance between flowers and fruit that has sustained ecosystems for millions of years. Yet these remarkable insects are far more than agricultural workers—they are sophisticated communicators, master navigators, and architectural geniuses who construct mathematically perfect cities in the air. As both ancient survivors and modern marvels, honey bees offer us a window into the complexity of evolution, the fragility of our ecosystems, and the profound interconnectedness of all life on Earth.

Facts

Here are some captivating insights into the world of honey bees:

- A honey bee’s wings beat an astonishing 200 times per second, creating the distinctive buzzing sound we associate with their flight, while allowing them to reach speeds of up to 15 miles per hour when unburdened by pollen.

- The waggle dance is a precise form of communication where foraging bees perform figure-eight movements to tell their hivemates the exact distance and direction to flowers, essentially creating a map through choreography.

- A single colony can fly the equivalent of traveling around the Earth three times to produce just one pound of honey, with individual bees visiting up to 5,000 flowers in a single day.

- Honey bees have five eyes—two large compound eyes made up of thousands of tiny lenses, and three simple eyes on top of their heads that detect light intensity and help with navigation.

- Worker bees are all female and perform different jobs throughout their six-week lifespan, starting as nurse bees caring for larvae, then moving to construction, guard duty, and finally foraging—a progression determined by age and pheromone signals.

- Bees can recognize human faces using the same pattern recognition techniques they employ to identify different flowers, demonstrating cognitive abilities once thought impossible for insects.

- The hexagonal cells in honeycomb represent one of nature’s most efficient structures, using the least amount of wax to create the maximum storage space—a mathematical principle known as the honeycomb conjecture that wasn’t formally proven until 1999.

Species

Honey bees belong to the genus Apis within a fascinating taxonomic framework that reveals their evolutionary relationships. Their complete classification is: Kingdom Animalia, Phylum Arthropoda, Class Insecta, Order Hymenoptera (which they share with wasps and ants), Family Apidae, Genus Apis.

Within the Apis genus, scientists recognize eight distinct species of honey bees, though the Western honey bee (Apis mellifera) is by far the most widespread and economically important. This species alone contains more than 25 recognized subspecies, including the Italian bee (A. m. ligustica), known for its gentle temperament and productivity; the Carniolan bee (A. m. carnica), prized for its hardiness in cold climates; and the African honey bee (A. m. scutellata), infamous for its defensive behavior.

The Eastern honey bee (Apis cerana) ranges across southern and eastern Asia and is the original host of the devastating Varroa mite. The giant honey bee (Apis dorsata) builds massive single-comb nests suspended from tree branches and cliff faces across South and Southeast Asia. Meanwhile, the dwarf honey bee (Apis florea) constructs tiny exposed combs barely larger than a hand. Other species include Apis laboriosa (the Himalayan giant honey bee), Apis nigrocincta, Apis koschevnikovi, and Apis andreniformis—each adapted to specific ecological niches across Asia.

Appearance

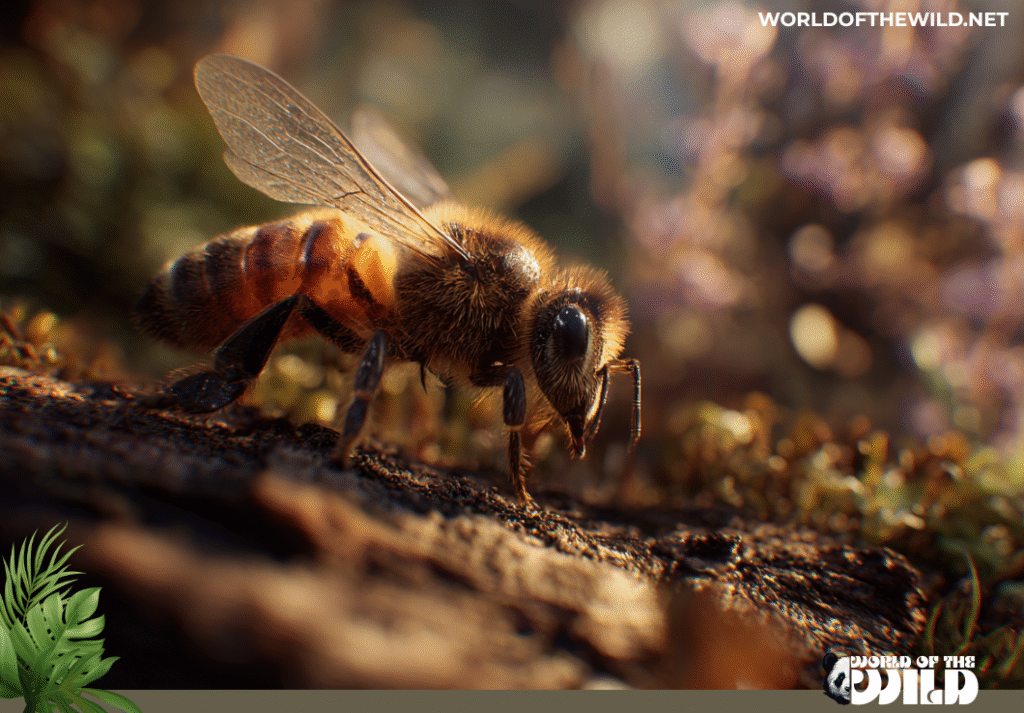

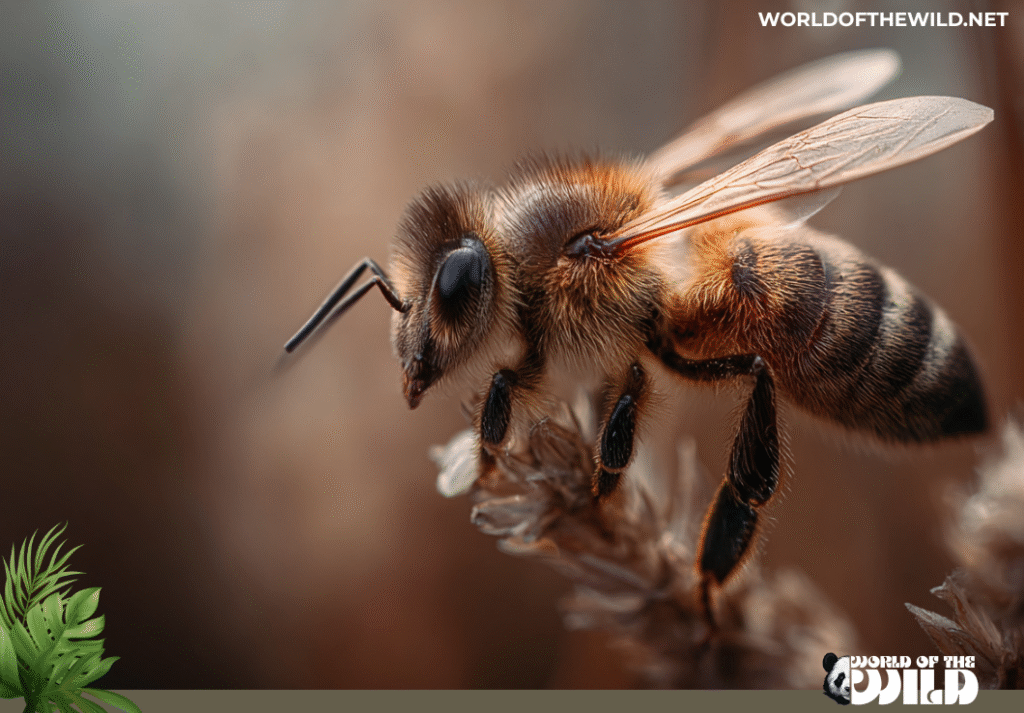

The honey bee is a masterpiece of miniature engineering, typically measuring between 12 to 15 millimeters in length, though this varies by caste. Queens, the largest members of the colony, can reach up to 20 millimeters, while male drones fall somewhere between workers and queens in size. A worker bee weighs approximately 100 milligrams—so light that it would take roughly 4,500 bees to equal one pound.

Their bodies display the classic three-part insect structure: head, thorax, and abdomen. The coloration varies by subspecies, but most honey bees exhibit distinctive bands of golden-yellow to dark brown or black across their abdomens, with fine hairs covering much of their bodies. These hairs aren’t merely decorative—they’re electrostatically charged structures that attract and hold pollen grains as the bee moves between flowers.

The head houses those five remarkable eyes, along with two segmented antennae containing thousands of sensory receptors for smell and touch. The thorax supports two pairs of translucent wings that hook together during flight and six jointed legs. The hind legs feature specialized structures called pollen baskets or corbiculae—concave areas surrounded by stiff hairs where bees pack and transport pollen back to the hive.

Perhaps most famously, female honey bees possess a barbed stinger connected to venom sacs. Unlike wasps, which can sting repeatedly, a honey bee’s barbed stinger typically remains lodged in mammalian skin, tearing away from the bee’s body along with the venom sac and parts of the digestive tract—a fatal sacrifice in defense of the colony.

Behavior

Honey bee behavior represents one of nature’s most sophisticated examples of social organization and collective intelligence. Within the hive, a rigid caste system governs the lives of three distinct types of bees: the queen, workers, and drones. Yet this hierarchy functions not through domination but through chemical communication and instinctive cooperation.

The queen’s primary role is reproduction, laying up to 2,000 eggs daily during peak season while releasing pheromones that maintain colony cohesion and suppress the reproductive capabilities of worker bees. Workers—sterile females comprising the vast majority of the colony—perform virtually all other tasks. Their job progression follows a remarkable age-based pattern: young bees clean cells and feed larvae, middle-aged bees build comb and process nectar, and older bees venture outside as foragers and guards. This division of labor emerges spontaneously from simple rules rather than central planning.

Communication among honey bees is extraordinarily complex. Beyond the famous waggle dance that communicates food source locations, bees use vibrations, sounds, and an elaborate chemical language of pheromones to coordinate activities. When a forager discovers a rich flower patch, she returns to perform her dance on the vertical comb, with the angle of her dance relative to the sun’s position indicating direction, and the duration of the waggle indicating distance.

Honey bees also demonstrate impressive cognitive abilities. They can count up to four, understand the concept of zero, recognize patterns and symmetry, and even engage in basic forms of abstract thinking. During flight, they navigate using the sun, landmarks, and Earth’s magnetic field, mentally mapping their territory across several square miles. When temperatures drop, worker bees cluster around the queen and brood, vibrating their flight muscles to generate heat and maintaining a steady 93°F at the cluster’s center even when outside temperatures plunge below freezing.

Evolution

The evolutionary story of honey bees stretches back approximately 100 million years to the Cretaceous period, when flowering plants were beginning their explosive diversification across the planet. The earliest bee ancestors were likely predatory wasps that began visiting flowers for nectar, gradually transitioning from hunters to pollen collectors as flowering plants became increasingly abundant.

Fossil evidence, including a remarkable 100-million-year-old specimen preserved in Burmese amber, shows primitive bees that display characteristics intermediate between wasps and modern bees. These ancient insects already possessed branched body hairs for carrying pollen, marking their evolutionary shift toward plant-pollinator mutualism—one of the most successful partnerships in natural history.

The genus Apis itself is relatively young in evolutionary terms, emerging approximately 25 to 30 million years ago during the Oligocene epoch. The ancestral honey bee likely originated in Southeast Asia, where the greatest diversity of Apis species still exists today. From this center of origin, honey bees radiated outward, with Apis mellifera eventually colonizing Europe, Africa, and the Middle East.

The evolution of social behavior in bees represents one of nature’s most fascinating puzzles. Scientists believe eusociality—the complex social structure where most individuals forgo reproduction to support a single breeding female—evolved through kin selection. Because of a quirk in bee genetics called haplodiploidy, where females develop from fertilized eggs and males from unfertilized eggs, worker bees are more closely related to their sisters than they would be to their own offspring. This creates a genetic incentive for cooperation that has shaped millions of years of evolution.

Climate fluctuations during the Pleistocene ice ages further shaped honey bee evolution, creating isolated populations that developed into the subspecies we recognize today, each adapted to specific regional conditions from the Mediterranean warmth to Northern European cold.

Habitat

Honey bees have achieved nearly global distribution, inhabiting every continent except Antarctica. Their natural range originally encompassed Europe, Africa, the Middle East, and western Asia, but human introduction has established populations in the Americas, Australia, and eastern Asia where they weren’t historically present. This remarkable adaptability speaks to their evolutionary flexibility and the universality of their relationship with flowering plants.

In the wild, honey bees are cavity nesters, seeking out hollow trees, rock crevices, or caves that provide protection from the elements and predators. The ideal natural hive location offers a cavity of approximately 40 liters in volume, positioned several meters above ground with a small entrance opening facing away from prevailing winds. Inside these spaces, bees construct their characteristic vertical wax combs, creating a three-dimensional city suspended in darkness.

Different honey bee species and subspecies have adapted to remarkably diverse environments. Apis mellifera thrives in habitats ranging from temperate forests and Mediterranean scrublands to African savannas and semi-arid regions. European subspecies have evolved tolerance for long, cold winters and brief flowering seasons, while African subspecies exhibit adaptations for heat, drought, and year-round activity. Some subspecies, like the Caucasian bee, have developed extra-long tongues to access nectar from deep flowers prevalent in their mountainous homeland.

The habitat requirements for honey bees extend beyond nesting sites to include adequate forage areas. A single colony requires access to diverse flowering plants across a radius of up to three miles, with different species blooming throughout the active season. Ideal habitats provide a succession of blooms from early spring through late fall, offering both nectar for energy and pollen for protein.

While honey bees adapt well to human-modified landscapes, they thrive best in areas with high floral diversity—something increasingly rare in modern agricultural landscapes dominated by monocultures. Urban environments, surprisingly, often provide excellent habitat, with gardens, parks, and flowering trees offering diverse, pesticide-reduced forage throughout the growing season.

Diet

Honey bees are specialized herbivores, feeding exclusively on nectar and pollen from flowering plants. This diet represents one of nature’s perfect nutritional packages: nectar provides carbohydrates for energy, while pollen supplies proteins, lipids, vitamins, and minerals essential for growth and development.

A foraging worker bee visits between 50 and 100 flowers during a single collection trip, using her long, tube-like tongue (proboscis) to reach deep into blossoms and lap up nectar. She stores this liquid in her honey stomach—a specialized crop separate from her digestive stomach—where enzymes begin breaking down complex sugars. Back at the hive, she regurgitates this nectar to house bees, who continue the process of enzymatic transformation and water evaporation, eventually converting it into honey.

Pollen collection requires different techniques. As bees crawl over flowers seeking nectar, pollen grains stick to their fuzzy bodies. They use specialized leg structures to comb pollen from their body hairs, moistening it with nectar and packing it into the pollen baskets on their hind legs. A single pollen load might contain four to five million grains representing multiple plant species.

Honey bees demonstrate sophisticated foraging strategies, with individual bees showing flower fidelity—visiting the same species of flower repeatedly during a single trip to maximize efficiency. Scout bees search for new food sources, evaluating flowers based on nectar quality, quantity, and accessibility before communicating their findings to the colony through the waggle dance.

The colony’s nutritional needs vary throughout the year. During spring buildup, when the queen is laying thousands of eggs daily, protein demand skyrockets and foragers prioritize pollen collection. In late summer and fall, bees focus on gathering nectar to stockpile honey reserves for winter survival. A typical colony might consume 200 to 300 pounds of honey annually, with winter clusters slowly consuming their stores to generate warmth and survive until spring flowers bloom again.

Water also plays a crucial role in the honey bee diet, used to dilute honey, cool the hive through evaporation, and feed developing larvae. Foragers collect water from streams, puddles, and dew, transporting it back to the hive where it’s distributed to meet various needs.

Predators and Threats

Honey bees face threats from numerous natural predators that have evolved alongside them for millions of years. Bears are perhaps the most formidable, willing to endure hundreds of stings to access protein-rich larvae and energy-dense honey. Skunks visit hives at night, scratching at entrances to lure out defending bees and consuming them. Birds, including bee-eaters and shrikes, pluck bees from the air, while smaller predators like spiders and dragonflies also take their toll on foragers.

The Asian hornet and its massive relative, the Asian giant hornet, represent particularly devastating predators. A single hornet can kill dozens of honey bees, and coordinated attacks by hornet groups can destroy entire colonies, decapitating bees and feeding the thoraxes to their own larvae. European honey bees have no evolved defense against these predators, though Asian honey bees have developed a remarkable counter-strategy: surrounding attacking hornets and vibrating their flight muscles to generate lethal heat.

Yet today’s most serious threats to honey bees come not from natural predators but from human activities and their cascading consequences. The Varroa destructor mite, accidentally spread globally through human commerce, parasitizes bees and transmits viruses, devastating colonies worldwide. These tiny external parasites feed on bee hemolymph (blood) and reproduce within brood cells, weakening bees and making them susceptible to diseases.

Industrial agriculture presents multiple challenges. Monoculture farming eliminates the floral diversity bees need for balanced nutrition, while fields bloom for brief periods and provide nothing for the rest of the season. Pesticides, particularly neonicotinoids and other systemic insecticides, contaminate the nectar and pollen bees collect, impairing navigation, reproduction, and immune function even at sublethal doses.

Habitat loss fragments bee populations and eliminates nesting sites as forests are cleared and natural areas are developed. Climate change disrupts the synchronized timing between flower blooming and bee emergence, creates extreme weather events that stress colonies, and allows parasites and diseases to expand into previously unsuitable regions.

Colony Collapse Disorder—a phenomenon where worker bees abandon their queen and brood—has periodically devastated beekeeping operations, though scientists believe it results from multiple stressors acting in combination rather than a single cause. The cumulative impact of poor nutrition, pesticide exposure, parasites, diseases, and management stress appears to overwhelm colonies’ ability to cope.

Reproduction and Life Cycle

The reproductive strategy of honey bees is as complex as their social structure, involving three distinct castes with dramatically different life cycles. The story begins with the queen, who mates just once in her lifetime during a dramatic nuptial flight. She leaves the hive as a virgin, flying high into the air where she attracts drones from multiple colonies through pheromone release. In rapid succession, she mates with 10 to 20 drones during this single flight, storing their sperm in her spermatheca—a specialized organ that keeps sperm viable for her entire life, potentially five years or more.

Following this mating flight, the queen never leaves the hive again unless the colony swarms. She lays eggs continuously, depositing a single egg into each carefully prepared wax cell. In an extraordinary demonstration of control, she determines each egg’s sex: fertilized eggs become female (workers or potential queens), while unfertilized eggs become males (drones). The queen can lay up to 2,000 eggs per day during peak season—more than her own body weight.

The fate of female larvae depends entirely on their diet. All female larvae initially receive royal jelly, a protein-rich secretion from nurse bees’ glands. After three days, most larvae transition to a diet of honey and pollen, developing into workers. However, larvae destined to become queens continue receiving royal jelly exclusively, triggering dramatic physiological changes through epigenetic mechanisms. These special larvae are raised in larger, vertically oriented queen cells, and this royal treatment transforms them into reproductive females with fully developed ovaries and dramatically extended lifespans.

The development from egg to adult takes 21 days for workers, 24 days for drones, and just 16 days for queens. Newly emerged workers immediately begin their progression through different jobs, living approximately six weeks during active seasons. Summer workers literally work themselves to death, their wings becoming tattered from constant flight. Winter workers, by contrast, can live four to six months, clustering quietly through cold weather to emerge and restart the colony in spring.

Drones lead remarkably different lives. Larger and stouter than workers, they perform no work within the hive, existing solely to mate. They loiter around hive entrances and congregate at “drone congregation areas”—mysterious locations where drones from multiple colonies gather in hopes of encountering a virgin queen. Successful mating comes at the ultimate price: the act of copulation tears away the drone’s reproductive organs, causing immediate death.

Colonies reproduce through swarming, one of nature’s most spectacular phenomena. When a hive becomes crowded, workers begin raising new queens. Before these virgin queens emerge, the old queen leaves with approximately half the colony’s workers in a massive, swirling cloud. This swarm clusters temporarily on a tree branch while scout bees search for a suitable cavity. Through a consensus-building process involving multiple scouts dancing to advertise different sites, the swarm eventually agrees on a new home and relocates en masse, establishing a daughter colony while the original hive continues with a new queen.

Population

The conservation status of managed honey bee colonies presents a complex and somewhat paradoxical picture. The Western honey bee (Apis mellifera) is not classified as endangered—in fact, there are more honey bee colonies globally today than at any point in history, with approximately 90 to 100 million managed hives worldwide. Beekeeping continues to expand, particularly in developing nations, and A. mellifera has successfully established feral populations on every continent except Antarctica.

However, these numbers mask serious underlying problems. While the species isn’t at risk of extinction, colony health has declined dramatically. Beekeepers in North America and Europe report annual losses of 30 to 40 percent—unsustainable rates that require constant colony replacement. These losses represent a significant economic burden and signal ecosystem stress that extends beyond managed bees to wild pollinators.

The situation for other Apis species varies considerably. Most wild honey bee species have not been comprehensively assessed for conservation status due to limited research in their native ranges. The giant honey bee (Apis dorsata) and Eastern honey bee (Apis cerana) remain relatively widespread, though habitat loss threatens local populations. Some subspecies of A. mellifera, particularly those adapted to specific ecological niches, face pressure from hybridization with introduced subspecies and loss of native habitat.

Wild or feral populations of honey bees—those living without human management—have declined substantially in many regions. In North America, feral colonies largely disappeared following the arrival of Varroa mites in the 1980s, though some resistant populations have since emerged. European populations face similar pressures, though wild colonies persist in some areas.

Population trends also reveal concerning geographic patterns. Developing nations in Africa, Asia, and South America are seeing growth in beekeeping, while industrialized nations struggle to maintain stable colony numbers despite increasing beekeeper effort. This divergence likely reflects differences in agricultural intensity, pesticide use, and landscape diversity.

The economic value of honey bee pollination services underscores their importance: estimates suggest bees contribute over $15 billion annually to U.S. agriculture alone and more than $200 billion globally. Yet this economic dependence has transformed beekeeping into an industrial activity, with colonies trucked thousands of miles to pollinate monoculture crops—a practice that stresses bees and facilitates disease spread.

Conclusion

The honey bee embodies one of nature’s most profound truths: that the smallest creatures often wield the greatest influence. These insects, individually insignificant and ephemeral, collectively shape ecosystems, nourish civilizations, and demonstrate the intricate interdependence that binds all living things. They are simultaneously ancient and fragile, abundant and threatened, familiar and profoundly mysterious.

Understanding honey bees means grappling with complexity—there are no simple villains or easy solutions to their decline. Rather, their struggles reflect the cumulative weight of a thousand human choices: the pesticides we spray, the habitats we pave, the climate we alter, and the simplified landscapes we create. Yet in this complexity also lies hope, for there are a thousand ways to help.

The honey bee’s story need not end in decline. By planting diverse flowers, reducing pesticide use, supporting sustainable agriculture, and protecting wild spaces, each of us can contribute to a future where these remarkable insects continue their ancient work. The choice before us is clear: we can continue down a path that treats nature as an inexhaustible resource to be exploited, or we can embrace the wisdom that honey bees have embodied for 100 million years—that cooperation, diversity, and attention to the needs of the whole create resilience and abundance for all.

The hum of bees in a summer garden is more than a pleasant sound. It is the music of life itself, a reminder that we are all connected in a web of mutual dependence. Protecting honey bees means protecting that web, and ultimately, protecting ourselves. The question is not whether we can afford to save the bees—it is whether we can afford not to.

Honey Bee – Quick Reference

Scientific Name: Apis mellifera (Western honey bee – the most common and widespread species)

Size:

- Worker bees: 12-15 mm (0.47-0.59 inches) in length

- Queen bees: Up to 20 mm (0.79 inches) in length

- Drones: 15-17 mm (0.59-0.67 inches) in length

- Weight: Approximately 100 mg (0.0035 oz) for worker bees

Region:

- Native Range: Europe, Africa, Middle East, and western Asia

- Introduced Range: Now found on every continent except Antarctica, including North America, South America, Australia, and eastern Asia

- Habitat Preference: Highly adaptable; found in temperate forests, Mediterranean regions, savannas, grasslands, semi-arid zones, agricultural areas, and urban environments across a wide range of climates from subarctic to tropical regions