On a warm summer afternoon, a flash of yellow and black streaks through the air with military precision, its low hum sending shivers down the spines of picnickers and gardeners alike. The hornet—nature’s most formidable wasp—commands respect and often fear wherever it appears. These powerful insects are far more than aggressive stingers, however. They are sophisticated architects, devoted parents, and essential pest controllers that have perfected the art of social living over millions of years. Despite their fearsome reputation, hornets represent one of nature’s most fascinating success stories, combining engineering prowess with complex social structures that rival any insect society on Earth. Understanding these remarkable creatures reveals not a monster to be feared, but a marvel of evolution worthy of our admiration and protection.

Facts

- Paper pioneers: Hornets invented paper long before humans—they create their nests by chewing wood fibers mixed with saliva, producing a material that predates Chinese papymaking by millions of years.

- Thermal regulation experts: Japanese giant hornets can generate heat with their flight muscles to cook enemy bees alive, vibrating their bodies to raise temperatures above 115°F (46°C) while staying just below their own lethal limit.

- Solar-powered insects: The Oriental hornet’s yellow tissue contains a pigment called xanthopterin that converts sunlight into electrical energy, making it the only known animal that can harvest solar power.

- Sophisticated navigation: Hornets can remember and recognize individual faces of their nestmates and use the sun’s position combined with internal timing mechanisms to navigate back to nests from miles away.

- Alcohol tolerance: European hornets are attracted to fermenting fruit and can consume alcohol concentrations that would kill most insects, often becoming visibly intoxicated but recovering without harm.

- Nighttime hunters: Unlike most wasps and bees, many hornet species are active after dark, with some equipped with enhanced vision that allows them to hunt in near-total darkness.

- Colony suicide mission: When a hornet colony is threatened beyond defense, workers may deliberately destroy their own nest and kill developing larvae rather than let predators benefit from their resources.

Species

Kingdom: Animalia

Phylum: Arthropoda

Class: Insecta

Order: Hymenoptera

Family: Vespidae

Genus: Vespa

Species: Approximately 22 recognized species

The genus Vespa encompasses all true hornets, distinguishing them from their smaller yellowjacket cousins in the genus Vespula and Dolichovespula. The most notable species include:

Asian Giant Hornet (Vespa mandarinia): The world’s largest hornet, reaching up to 2 inches (5 cm) in length with a wingspan of 3 inches (7.6 cm). Native to East and Southeast Asia, this species gained notoriety as the “murder hornet” when detected in North America in 2019.

European Hornet (Vespa crabro): The only hornet species native to Europe and the most widely distributed, now also established across much of North America after being introduced in the 1800s. These are notably less aggressive than their Asian relatives.

Oriental Hornet (Vespa orientalis): Recognizable by its reddish-brown coloring with distinctive yellow stripes, this species thrives in arid and semi-arid regions across the Middle East, Mediterranean, and parts of Africa.

Yellow-Legged Hornet (Vespa velutina): Also called the Asian hornet, this invasive species has spread rapidly across Europe since 2004, posing significant threats to honeybee populations.

Black-Bellied Hornet (Vespa basalis): A medium-sized species native to Southeast Asia, recognized by its distinctive black abdomen with minimal yellow markings.

Each species has evolved specific adaptations to its environment, from the giant hornet’s ability to hunt in large raiding parties to the Oriental hornet’s unique solar-energy harvesting capabilities.

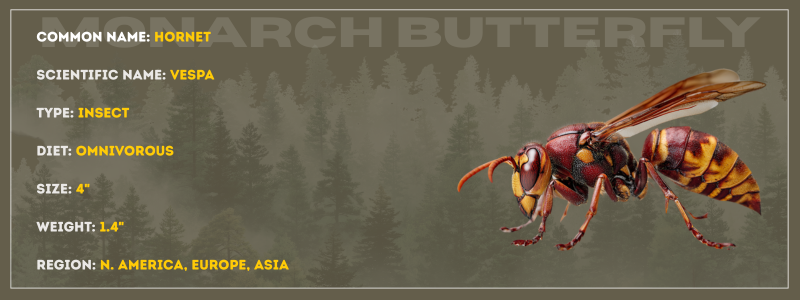

Appearance

Hornets are the giants of the wasp world, with most species substantially larger than common wasps or yellowjackets. Size varies dramatically by species and caste: Asian giant hornet queens can reach a staggering 2.2 inches (5.5 cm) in length, while European hornet workers typically measure 0.8-1.4 inches (2-3.5 cm). Workers are always smaller than queens but larger than males (drones).

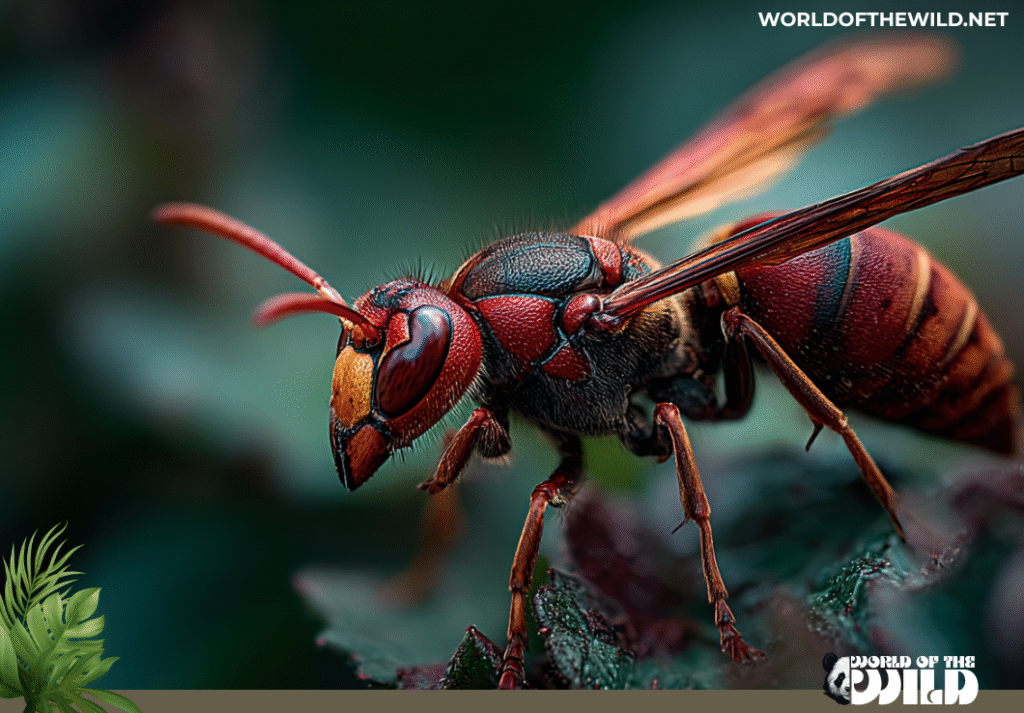

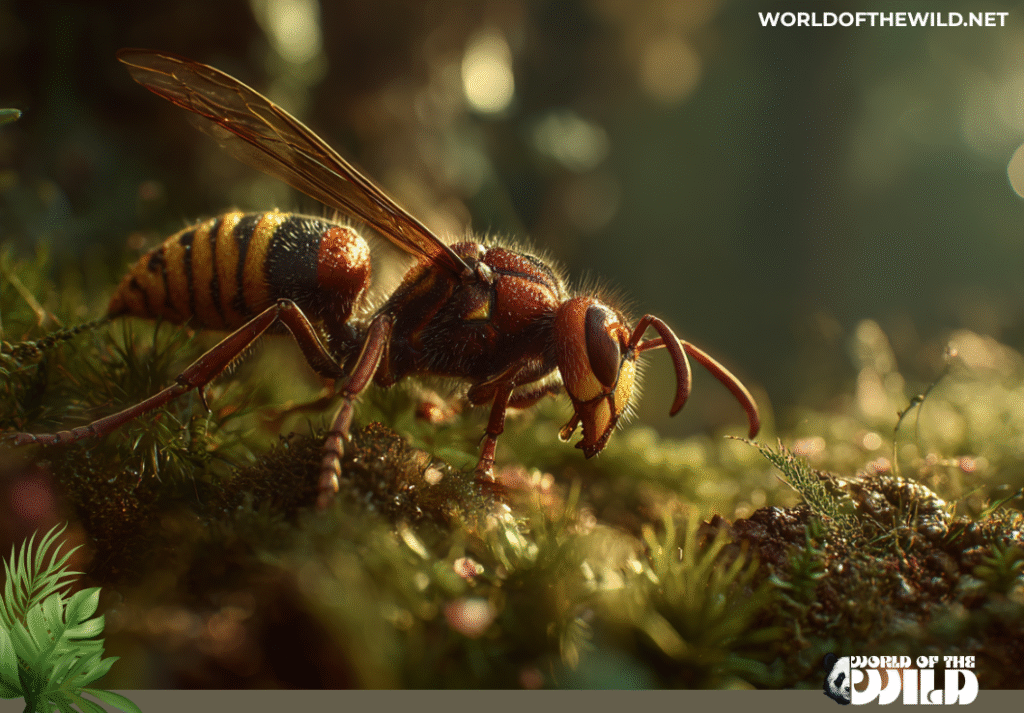

The classic hornet appearance features bold warning coloration—nature’s way of advertising danger. Most species display striking patterns of yellow or orange alternating with black or dark brown bands across their abdomens. The European hornet sports a reddish-brown thorax with yellow and black abdominal stripes, while the Asian giant hornet presents an intimidating orange head with a dark brown thorax and yellow-orange banded abdomen.

Their bodies are divided into three distinct segments: the head houses large compound eyes (often brown or reddish), powerful mandibles for chewing wood and prey, and relatively short antennae with 12 segments in females and 13 in males. The thorax is robust and muscular, supporting two pairs of transparent, amber-tinted wings and six powerful legs. The abdomen tapers to a pointed end, where the infamous stinger—a modified ovipositor—remains sheathed when not in use.

Hornets are covered in fine hairs that give them a slightly fuzzy appearance, and their exoskeletons have a waxy coating that provides waterproofing. Their wings, when at rest, fold longitudinally along the body, a characteristic that distinguishes them from bees. Perhaps most striking are their large, prominent eyes that provide excellent vision and their substantial, downward-facing mandibles capable of decapitating prey insects in a single bite.

Behavior

Hornets are highly social insects living in sophisticated matriarchal societies where a single queen rules over hundreds or even thousands of sterile female workers. Their behavioral complexity rivals that of honeybees and ants, with distinct castes performing specialized roles throughout the colony’s annual cycle.

The daily rhythm of a hornet nest begins at dawn, when workers emerge to hunt protein-rich prey including flies, caterpillars, grasshoppers, and even other bees and wasps. Hornets are apex predators in the insect world, using their powerful mandibles to capture, kill, and dismember prey before carrying muscle tissue back to feed developing larvae. Unlike bees, adult hornets primarily consume liquids—nectar, tree sap, and the nutritious secretions that larvae produce in exchange for solid food, creating a unique reciprocal feeding relationship between generations.

Communication within the colony occurs through multiple channels. Hornets employ chemical signals (pheromones) to mark territory, signal danger, coordinate attacks, and maintain social cohesion. When a hornet stings a threat, it releases an alarm pheromone that can trigger aggressive responses from nestmates up to 15 feet away. They also use tactile communication through antennation (touching antennae) and perform sophisticated dances similar to honeybees to communicate food source locations.

Social hierarchy is strictly maintained. The queen, largest of all colony members, focuses exclusively on egg-laying during the productive season, producing up to 200-300 eggs daily at peak times. Workers perform age-related tasks: younger workers maintain the nest, feed larvae, and regulate temperature by fanning wings or collecting water for evaporative cooling, while older workers transition to foraging, hunting, and nest defense.

Hornets demonstrate remarkable intelligence and learning capacity. They can recognize individual nestmates, remember complex landscape features for navigation, and even exhibit what appears to be play behavior in controlled settings. European hornets uniquely forage at night, using enhanced vision and exceptional spatial memory to navigate in darkness. Some species show primitive tool use, employing mud or plant material to repair or modify nests.

Defensive behavior is where hornets’ fearsome reputation originates. Unlike honeybees that die after stinging, hornets can sting repeatedly, injecting venom that causes intense pain and, in sensitive individuals, potentially fatal allergic reactions. However, most species are defensive rather than aggressive—they attack when they perceive threats to the nest, not out of mere proximity. The exception is when colonies are hunting, particularly the Asian giant hornet’s spectacular mass raids on honeybee hives, where dozens of hornets can destroy an entire colony of 30,000 bees in a few hours.

Evolution

Hornets belong to the ancient order Hymenoptera, which emerged during the Triassic period approximately 240 million years ago, long before the first flowers appeared. The lineage that would eventually produce modern hornets diverged from other wasps during the Cretaceous period (145-66 million years ago), a time of explosive diversification for flowering plants and their insect pollinators.

The family Vespidae, which includes hornets, yellowjackets, and paper wasps, evolved from solitary hunting wasps. Fossil evidence suggests that social behavior in wasps emerged multiple times independently, with the ancestor of true hornets developing eusociality (complex colonial living with reproductive division of labor) roughly 75-100 million years ago. This evolutionary innovation coincided with the rise of angiosperm forests, which provided both the wood fibers for nest construction and abundant prey insects.

The genus Vespa likely originated in Southeast Asia during the Oligocene epoch (34-23 million years ago), where the greatest diversity of hornet species still exists today. From this tropical crucible, hornets radiated outward, with different lineages adapting to temperate climates, arid environments, and high-altitude regions. The European hornet (Vespa crabro) represents one such successful colonization of temperate zones, having spread across Europe and later, through human introduction, to North America.

Molecular phylogenetic studies reveal that hornets’ closest relatives are the tropical Provespa wasps, night-flying species that share the hornets’ large size and predatory lifestyle. The evolution of hornets’ distinctive traits—including their size, nocturnal capabilities in some species, and sophisticated paper-making abilities—represents adaptations to predatory efficiency and competitive superiority in insect communities.

Key evolutionary innovations include the development of powerful venom with both paralytic and pain-inducing compounds, enhanced visual systems for low-light hunting, and increasingly complex social structures that allowed colonies to grow larger and defend more effectively against vertebrate predators. The Oriental hornet’s solar-energy-harvesting yellow pigment represents one of evolution’s most unusual experiments, though its exact adaptive advantage remains debated among scientists.

Climate fluctuations during the Pleistocene ice ages (2.6 million to 11,700 years ago) shaped current hornet distributions, fragmenting populations and creating the distinct species we recognize today. As glaciers advanced and retreated, hornet populations contracted to refuge areas and then recolonized, occasionally hybridizing where ranges overlapped and creating the complex genetic patterns researchers now study.

Habitat

Hornets occupy diverse habitats across much of the Northern Hemisphere, with their range centered in temperate and subtropical regions of Europe, Asia, and North Africa. A few species extend into tropical areas, while human introduction has established populations in North America and, more recently, parts of South America.

The European hornet (Vespa crabro) ranges from Britain and Scandinavia eastward through Russia to the Ural Mountains and south to the Mediterranean. Introduced populations thrive in eastern North America from Ontario to Georgia. These hornets prefer deciduous and mixed forests, forest edges, parks, and suburban areas where mature trees provide nesting cavities and abundant prey.

Asian hornets show the greatest habitat diversity. The Asian giant hornet inhabits forests and mountains from India through China, Korea, and Japan to the Russian Far East, favoring temperate forests at elevations up to 6,000 feet (1,800 m). The Oriental hornet has adapted to arid and semi-arid environments, thriving in Mediterranean scrublands, desert oases, and even urban areas across North Africa, the Middle East, and southern Europe. The yellow-legged hornet occupies subtropical forests of Southeast Asia and has successfully invaded urban and agricultural areas across Western Europe.

Hornets require specific habitat features: mature trees or structures with cavities for nest sites, accessible water sources, abundant flying insect populations for prey, and flowering plants or sap-producing trees for carbohydrate nutrition. European hornets particularly favor oak, beech, and willow trees, often nesting in hollow trunks, abandoned buildings, or even large bird boxes. Asian giant hornets typically excavate underground nests or occupy rodent burrows, while some tropical species build exposed aerial nests suspended from tree branches.

Microhabitat selection is critical for colony success. Hornets choose nest sites with specific temperature and humidity characteristics, typically locations that remain relatively cool and moist during summer. Foraging ranges extend 500-1,000 meters from the nest, though scouts may travel up to 2-3 kilometers when searching for resources.

Climate change is currently shifting hornet distributions northward and to higher elevations. Warmer winters increase queen survival rates, allowing species like the yellow-legged hornet to colonize previously unsuitable regions. Urban heat islands create artificial habitats where hornets thrive year-round in some cities, even as their natural forest habitats shrink.

Diet

Hornets are carnivorous hunters as workers and nectar-feeding adults, occupying a unique ecological niche as both predators and pollinators. This dual dietary strategy supports their large colonies’ enormous energy demands and protein requirements.

Adult hornets primarily consume carbohydrates in liquid form: flower nectar, honeydew (sugary secretions from aphids), tree sap, and fermenting fruit juices. They show particular attraction to oak and birch sap, often stripping bark to access flowing sap in spring. Late-season hornets become frequent visitors to rotting fruit, where they consume fermented juices and occasionally become intoxicated. While feeding on these sugar sources, adult hornets inadvertently pollinate flowers, though they are less efficient pollinators than bees due to their smoother bodies and more aggressive demeanor.

The protein requirements for feeding larvae drive hornets’ hunting behavior. Workers are tireless predators, hunting from dawn until dusk (or through the night in nocturnal species). They prey primarily on other insects: flies, beetles, caterpillars, grasshoppers, crickets, moths, bees, and smaller wasps. Hunting hornets use visual cues to detect movement, then strike with remarkable speed, grasping prey with their legs and delivering a killing bite with powerful mandibles that can sever an insect’s head in seconds.

Large prey items are butchered on-site. A hunting hornet will remove wings, legs, and other indigestible parts, creating compact “meat balls” from the protein-rich flight muscles and soft tissues to carry back to the nest. A single large hornet colony may consume 500-1,000 insects daily at peak season, making them significant predators in their ecosystems.

The most dramatic hunting behavior belongs to the Asian giant hornet, which conducts organized raids on honeybee colonies. Scout hornets mark beehives with pheromones, recruiting dozens of nestmates for coordinated attacks. These hornets can kill 40 bees per minute, decimating entire colonies of 30,000 bees in just a few hours. They then occupy the hive, feeding on bee larvae and pupae for days or weeks. This devastating efficiency has made them a serious threat to both wild and managed bee populations.

Upon returning to the nest, hunting workers distribute protein to larvae, which cannot consume solid food. In exchange, larvae secrete a clear, protein-rich fluid called vespa amino acid mixture (VAAM) that adult workers eagerly consume. This trophallaxis—reciprocal feeding between adults and larvae—creates a sophisticated food-sharing network that efficiently distributes nutrients throughout the colony.

Hornets also exhibit opportunistic scavenging, feeding on carrion, fish scraps, and even raw meat at butcher shops or picnic sites, though hunting live prey remains their primary protein-acquisition strategy.

Predators and Threats

Despite their formidable defenses, hornets face numerous predators and mounting anthropogenic threats that challenge their survival across many regions.

Natural predators vary by geographic location but typically include vertebrates with adaptations to deal with stinging insects. Birds are primary hornet predators: bee-eaters, European honey buzzards, and shrikes regularly prey on hornets, with honey buzzards specialized for raiding wasp and hornet nests. These raptors have thick facial feathers that protect against stings and can destroy entire colonies. Mammals including badgers, bears, and raccoons raid nests for protein-rich larvae and pupae, seemingly tolerating hundreds of stings to access this nutritious food. Asian black bears in Japan specifically target Asian giant hornet nests despite the extreme danger.

Insect predators also take their toll. Dragonflies catch hornets in flight, while robber flies ambush them at flowers. Parasitic flies and wasps target hornet larvae, and certain beetles invade nests to consume brood. Hornets themselves are cannibalistic toward weak or injured colony members, and rival hornet species will occasionally raid each other’s nests.

The most sophisticated predator-prey relationship exists between Asian honeybees and giant hornets. Japanese honeybees have evolved a remarkable defense called “heat-balling”: when a hornet scout approaches, hundreds of bees surround it and vibrate their flight muscles, raising the temperature to 115°F (46°C)—just below the bees’ thermal death point but above the hornet’s tolerance. This cooperative defense can kill attacking hornets before they mark the hive for mass attack.

Anthropogenic threats pose increasingly severe challenges to hornet populations:

Habitat destruction leads the list of human-caused threats. Deforestation, agricultural intensification, and urbanization eliminate the mature trees with cavities that hornets require for nesting. Forest fragmentation isolates populations and reduces prey diversity.

Pesticide exposure causes both direct mortality and sublethal effects that impair navigation, learning, and reproduction. Neonicotinoid insecticides, while primarily targeting agricultural pests, accumulate in hornets through contaminated prey insects. Hornets that forage in agricultural areas face particularly high exposure risks.

Direct persecution by humans remains substantial. In many regions, people destroy hornet nests on sight, driven by fear rather than actual threat. In Asia, hornet nests are harvested for traditional medicine and food (larvae are considered a delicacy), creating harvest pressure on wild populations.

Invasive species introductions work both ways. The yellow-legged hornet’s invasion of Europe has sparked massive eradication campaigns, while the Asian giant hornet’s appearance in North America triggered similar responses. However, hornets also suffer from competition with introduced species like European paper wasps and from diseases spread by managed honeybees.

Climate change presents complex challenges. While warming temperatures may expand ranges northward, they also disrupt synchronization between hornets’ emergence and peak prey availability. Extreme weather events—intense storms, droughts, and heat waves—can destroy nests or deplete food sources at critical times.

Ironically, some hornet species face persecution as invasive pests in some regions while suffering population declines in their native ranges, creating a conservation paradox that complicates management strategies.

Reproduction and Life Cycle

The hornet life cycle follows an annual pattern in temperate regions, beginning and ending with a single inseminated queen. This remarkable reproductive strategy builds massive colonies from a single individual, only to collapse each autumn in a carefully orchestrated process.

Spring: Colony Founding

The cycle begins in early spring when queens emerge from hibernation. These queens—the sole survivors of the previous year’s colony—mated in autumn before their natal nest died off. After overwintering in leaf litter, tree bark crevices, or building spaces, queens must quickly find suitable nest sites and begin construction.

Working alone, a founding queen chews wood fibers from dead trees, fence posts, or woody stems, mixing them with saliva to create the first paper envelope and a few initial brood cells. She lays her first eggs—typically 10-20—in these cells and must simultaneously construct, hunt, and incubate. Early spring is the most vulnerable period; queens face high mortality from cold, starvation, or predation.

Early Summer: Worker Emergence

After 5-8 days, eggs hatch into larvae. The queen feeds them masticated insects for approximately 10-14 days through multiple larval instars. Larvae then pupate for another 10-14 days before emerging as adult workers. This first generation consists entirely of small female workers, sterile daughters of the queen.

Once workers emerge, the colony enters exponential growth. The queen ceases all tasks except egg-laying, while workers assume foraging, nest construction, brood care, and defense. Workers build additional layers of paper envelope around expanding comb structures, sometimes creating nests containing 3,000-5,000 cells by season’s end.

Mid to Late Summer: Colony Peak

By mid-summer, successful colonies contain hundreds to thousands of workers (European hornets: 300-500; Asian giant hornets: 100-1,000; smaller species: 100-300). The queen reaches peak egg-laying productivity, producing 200-300 eggs daily. The nest hums with activity 24 hours a day as nocturnal species continue foraging after dark.

Late Summer to Autumn: Reproductive Phase

As days shorten and autumn approaches, the colony’s priorities shift dramatically. The queen begins laying unfertilized eggs in larger cells. These develop into males (drones), as Hymenoptera use haplodiploidy—males develop from unfertilized eggs and carry only maternal genes. Simultaneously, workers construct special large cells where the queen lays fertilized eggs that receive abundant food and develop into new queens rather than workers. The mechanism behind caste determination remains partially understood but involves both genetic factors and differential feeding.

New queens and males emerge in late summer to early autumn. Males do not work but instead leave the nest to congregate at landmarks where they await virgin queens. Mating typically occurs during these congregation flights, often involving multiple males per queen. Males die shortly after mating, having fulfilled their sole biological purpose.

Autumn: Colony Decline

As temperatures drop and prey becomes scarce, the old queen stops laying. Workers become less coordinated; some abandon nest duties to feed on fermenting fruit. Remarkably, workers may even begin destroying remaining larvae and pupae, an apparent adaptation to prevent resources from being wasted on individuals that cannot survive winter.

The old queen dies, as do all workers and any males still alive. Only the newly mated queens survive, dispersing to find hibernation sites where they’ll remain dormant for 6-8 months until spring triggers the cycle anew.

Lifespan: Queens live approximately one year, though they spend 6-8 months hibernating. Workers live 3-6 weeks during the active season. Males live only a few weeks, just long enough to mate.

Some tropical hornet species maintain perennial colonies where queens live multiple years, but temperate species invariably follow this annual pattern—a complete societal rise and fall compressed into a single season.

Population

Assessing global hornet populations presents significant challenges as most species lack comprehensive monitoring programs. Unlike charismatic vertebrates, invertebrate conservation status often relies on limited data, indirect indicators, and expert assessments rather than systematic censuses.

Conservation Status:

Most hornet species are not formally evaluated by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List. The European hornet (Vespa crabro) and several Asian species are presumed to have stable populations and would likely qualify as Least Concern if assessed. However, the absence of formal assessments should not be confused with security—many species may be declining without detection.

Population Trends:

Evidence suggests mixed trends across different species and regions:

Declining populations: Several European studies document significant declines in hornet observations over the past 30-50 years, particularly in intensively farmed landscapes. German and Dutch surveys show 30-60% reductions in hornet nest density in agricultural areas compared to forests. These declines mirror broader patterns of insect decline documented across Europe and North America, where flying insect biomass has decreased by 75% or more in some protected areas over recent decades.

Stable populations: In intact forest habitats and well-managed suburban areas, European hornet populations appear relatively stable. Protected areas with mature forests maintain healthy hornet populations, suggesting that habitat protection can ensure persistence.

Expanding populations: Some species show range expansions and population increases, particularly invasive species in non-native ranges. The yellow-legged hornet has exploded across Western Europe since its introduction around 2004, now established in France, Spain, Portugal, Italy, Belgium, Netherlands, and southern England. Asian giant hornets have recently established in the Pacific Northwest of North America, though aggressive eradication efforts may have eliminated this foothold.

Population Estimates:

Precise global population numbers remain unknown for any hornet species. Population estimation for social insects typically focuses on nest density rather than individual counts. European hornet densities in favorable habitats range from 1-10 nests per square kilometer, while more common yellowjackets may achieve 50-100 nests per square kilometer. Extrapolating conservatively, European hornets probably number in the tens of millions of colonies across their range, translating to billions of individual hornets during peak season (though most are workers that live only weeks).

Asian giant hornets, despite their fearsome reputation, appear to be less common, with some Japanese studies suggesting declining populations in certain regions, possibly due to climate change affecting synchronization with prey species, habitat loss, and harvesting pressure.

Monitoring Challenges:

Several factors complicate hornet population assessment. Their cryptic nests (often hidden in tree cavities or underground), annual colony cycles that make year-to-year comparisons difficult, and the lack of standardized monitoring protocols all contribute to uncertainty. Most data comes from opportunistic observations, pest control records, or citizen science projects rather than systematic surveys.

Regional Variation:

Population health varies dramatically by region. Southeast Asian hornets face habitat loss from palm oil plantations and logging but benefit from traditional agroforestry systems. European hornets decline in agricultural areas but adapt well to suburban environments with mature trees. This patchwork pattern makes overall assessment difficult.

Conclusion

Hornets stand as testament to evolution’s power to craft sophisticated solutions to life’s challenges. These magnificent insects—far from being mere dangerous pests—are ecological engineers, master architects, devoted parents, and remarkably intelligent creatures whose complex societies rival our own in organizational sophistication. From the paper-inventing European hornet maintaining night vigils over its colony to the solar-powered Oriental hornet harvesting sunlight in desert heat, each species reveals unique adaptations refined over millions of years.

Yet hornets face an uncertain future. Habitat destruction, pesticide exposure, climate disruption, and human persecution threaten populations while our understanding of their conservation needs remains incomplete. The same insects that help control agricultural pests and pollinate flowers are often destroyed on sight, victims of fear and misunderstanding rather than genuine threat.

Perhaps the most important lesson hornets teach is humility. These creatures we casually dismiss or destroy without thought are marvels of biological engineering, exhibiting behaviors—tool use, facial recognition, complex communication, coordinated hunting—that hint at forms of intelligence we’re only beginning to understand. A hornet nest represents the collaborative achievement of thousands of individuals working in harmony, building beauty from wood fibers and spit, defending their family with fearless dedication.

As we stand at a crossroads for insect conservation, with global populations declining at alarming rates, we must decide whether hornets and countless other “unloved” species deserve protection. The answer should be clear: every species has intrinsic value, and hornets in particular serve essential roles in maintaining healthy ecosystems. By learning to coexist with these powerful insects—respecting their space, protecting their habitats, and appreciating their ecological contributions—we enrich both the natural world and our own understanding of life’s magnificent diversity.

The next time you encounter a hornet, pause before reacting with fear. Watch it hunt with precision, navigate with purpose, or carefully tend its paper nest. You’re witnessing not a monster but a miracle—a small but fierce testament to nature’s genius, deserving of our wonder and our protection.

Hornet Quick Reference Guide

Scientific Name

Genus: Vespa

Common Species:

- Asian Giant Hornet: Vespa mandarinia

- European Hornet: Vespa crabro

- Oriental Hornet: Vespa orientalis

- Yellow-Legged Hornet: Vespa velutina

- Black-Bellied Hornet: Vespa basalis

Size

Length:

- Queens: 1.2–2.2 inches (3–5.5 cm)

- Workers: 0.8–1.4 inches (2–3.5 cm)

- Males (Drones): 0.8–1.6 inches (2–4 cm)

Wingspan:

- Up to 3 inches (7.6 cm) in the largest species

Weight:

- Queens: 0.2–0.35 ounces (6–10 grams)

- Workers: 0.07–0.14 ounces (2–4 grams)

Note: The Asian Giant Hornet is the largest species, while the European Hornet is medium-sized. Size varies considerably by species and caste.

Region

Geographic Range:

- Europe: Western Europe to the Ural Mountains, Scandinavia to Mediterranean

- Asia: India through China, Korea, Japan, Southeast Asia to the Russian Far East

- North Africa: Mediterranean coast, Middle East regions

- North America: Eastern United States and southeastern Canada (introduced European Hornet)

Habitat Types:

- Deciduous and mixed forests

- Forest edges and clearings

- Suburban areas with mature trees

- Mediterranean scrublands (Oriental Hornet)

- Mountains up to 6,000 feet (1,800 m) elevation

- Desert oases (Oriental Hornet)

Diet

Adult Hornets (Workers & Queens):

- Primary: Carbohydrates from nectar, tree sap, honeydew, and fermenting fruit juices

- Secondary: Protein-rich secretions from larvae (vespa amino acid mixture)

Larvae:

- Exclusive: Protein from insects hunted and processed by workers

Prey Items (Hunted by Workers):

- Flies, beetles, and moths

- Caterpillars and grasshoppers

- Crickets and other wasps

- Honeybees and smaller wasp species

- Occasionally: carrion and raw meat (opportunistic scavenging)

Feeding Classification:

- Adults: Omnivorous (primarily nectarivorous with opportunistic protein consumption)

- Larvae: Carnivorous (exclusively insectivorous)

- Colony Overall: Predatory with significant impact on local insect populations (500–1,000 insects consumed daily per colony at peak season)