Few insects inspire quite the same visceral reaction as the yellow jacket. At summer picnics and backyard barbecues, their distinctive black-and-yellow forms hovering near soda cans and hamburgers trigger an almost universal wave of anxiety. Yet beneath their aggressive reputation lies a creature of remarkable complexity—a highly intelligent social insect that plays a crucial role in maintaining ecological balance. These aerial predators are master architects, sophisticated communicators, and devoted defenders of their colonies. While their painful stings have earned them few admirers, yellow jackets deserve recognition as one of nature’s most effective pest controllers and misunderstood marvels of the insect world.

Facts

- Colony suicide mission: Unlike honeybees, yellow jacket workers can sting repeatedly without dying, making them far more dangerous when defending their nest. Each worker can sting multiple times because their stinger lacks the barbed structure that causes honeybees to die after a single sting.

- Underground metropolises: The largest yellow jacket nests can contain over 5,000 workers and reach the size of a basketball, with most of the structure hidden underground in abandoned rodent burrows.

- Facial recognition experts: Yellow jackets can recognize individual faces of their colony members and remember human faces that have threatened their nest for days afterward, targeting those individuals preferentially.

- Chemical warfare specialists: When a yellow jacket stings, it releases alarm pheromones that can persist for hours, marking the threat and summoning nestmates to join the attack—this is why disturbing a nest can result in mass stinging events.

- Seasonal personality change: Yellow jackets become significantly more aggressive in late summer and fall because their natural food sources dwindle and the colony begins to break down, making workers more desperate and irritable.

- Speed demons of the insect world: These wasps can fly up to 30 miles per hour and are capable of making sharp turns and hovering with remarkable precision, making them formidable hunters.

- Scavenger cleanup crew: Yellow jackets consume enormous quantities of dead insects, rotting fruit, and carrion, making them important decomposers in addition to their role as predators of living pests.

Species

Yellow jackets belong to the genus Vespula and Dolichovespula within the taxonomic hierarchy:

- Kingdom: Animalia

- Phylum: Arthropoda

- Class: Insecta

- Order: Hymenoptera

- Family: Vespidae

- Genus: Vespula (most common species) and Dolichovespula

- Species: Multiple, including Vespula vulgaris (common yellow jacket)

There are approximately 16 species of yellow jackets in North America alone, with dozens more worldwide. The most frequently encountered species include the Eastern yellow jacket (Vespula maculifrons), the Western yellow jacket (Vespula pensylvanica), the German yellow jacket (Vespula germanica), and the common yellow jacket (Vespula vulgaris). The German yellow jacket, an invasive species introduced to North America, has become particularly problematic due to its adaptability and aggressive nature.

Closely related species in the Dolichovespula genus, such as the bald-faced hornet (Dolichovespula maculata), are sometimes grouped with yellow jackets despite their different coloring. These aerial nesters build the familiar paper nests seen hanging from trees and building eaves.

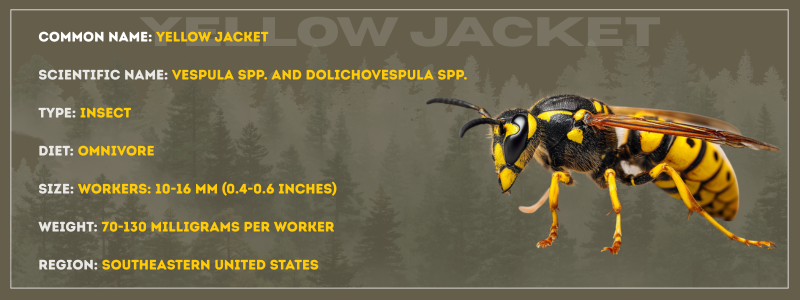

Appearance

Yellow jackets are robust wasps with the iconic warning coloration that gives them their name. Workers, the most commonly encountered caste, measure between 10 to 16 millimeters in length—roughly half an inch. Their bodies feature bold alternating bands of bright yellow and deep black, though the exact pattern varies by species. Some species display more yellow coloring, while others appear predominantly black with yellow markings.

The exoskeleton is smooth and shiny, lacking the fuzzy hair characteristic of bees—a key distinguishing feature. Their bodies follow the classic wasp architecture: a distinctive narrow “waist” connecting the thorax to the abdomen, creating the familiar pinched silhouette. They possess two pairs of translucent wings that fold longitudinally when at rest, another trait that separates them from bees.

Yellow jackets have large compound eyes, typically dark amber or black, positioned on either side of their triangular heads. Their antennae are segmented and constantly in motion, sampling chemical signals from their environment. Queens are noticeably larger than workers, reaching up to 20 millimeters in length, with a more robust abdomen to accommodate their reproductive organs. Males, or drones, are similar in size to workers but can be identified by their longer antennae and lack of a stinger.

The weight of a yellow jacket worker ranges from 70 to 130 milligrams—light enough to land on your skin without you noticing until they sting. Their coloration serves as aposematic warning to potential predators, advertising their defensive capabilities.

Behavior

Yellow jackets are quintessentially social insects, living in highly organized colonies with a sophisticated division of labor. Each colony operates with a strict caste system comprising a single queen, sterile female workers, and males produced later in the season. The queen controls her empire through chemical signals called pheromones, which regulate worker behavior and suppress their reproductive capabilities.

Workers display remarkable behavioral flexibility, transitioning through different roles as they age. Younger workers tend to remain inside the nest, caring for larvae, building comb, and maintaining optimal temperature and humidity. Older workers venture outside as foragers, hunters, and nest defenders. These aerial predators hunt other insects with stunning efficiency, paralyzing prey like caterpillars, flies, and aphids with precise stings before carrying them back to the nest to feed developing larvae.

Communication within the colony occurs primarily through chemical signals and tactile interactions. When workers discover food sources, they return to the nest and perform what scientists call “jostling runs”—rapid movements through the nest that attract other workers and transfer scent information. Unlike honeybees, yellow jackets do not perform elaborate dances, instead relying on more direct chemical communication.

Their defensive behavior is legendary and strategic. Guard workers patrol near nest entrances, screening incoming traffic and assessing potential threats. When danger approaches, guards release alarm pheromones that rapidly recruit other workers to the defense. This chemical signal can linger in the area, causing yellow jackets to remain aggressive for extended periods after an initial disturbance. Their stings are not only painful but also deliver venom that can trigger the release of more alarm pheromones from the victim’s body, intensifying the attack.

Yellow jackets demonstrate impressive learning abilities and memory. They can navigate complex environments using visual landmarks, remember the locations of productive food sources, and recognize specific individuals—both nestmates and threats. Research has shown they can even solve simple puzzles to access food rewards.

Evolution

Yellow jackets belong to the family Vespidae, a lineage of social wasps that emerged during the Cretaceous period, approximately 100 million years ago. The Vespidae family likely evolved from solitary hunting wasps, with social behavior developing as a successful evolutionary strategy for raising offspring and defending resources.

The transition from solitary to social living represents one of evolution’s major innovations. Early wasp ancestors probably displayed primitive social behaviors, with females guarding their nests and provisioning their young. Over millions of years, these behaviors became more elaborate, eventually leading to the complex societies seen in modern yellow jackets.

The genus Vespula itself is relatively young in evolutionary terms, diversifying primarily during the Miocene epoch, around 20 million years ago. During this period, expanding temperate forests and seasonal climates created ideal conditions for social wasps that could build large colonies during warm months and overwinter as solitary queens.

Fossil evidence of wasps is relatively rare due to their delicate bodies, but preserved specimens in amber have provided glimpses into their ancient forms. These fossils reveal that the basic body plan of wasps—narrow waist, folding wings, and powerful mandibles—has remained remarkably stable over tens of millions of years.

The evolutionary success of yellow jackets stems from their behavioral flexibility and adaptability. Their ability to exploit diverse food sources, from nectar and insects to human refuse, has allowed them to thrive in varied environments. The development of sophisticated chemical communication and nest defense systems enabled colonies to grow large and productive, increasing reproductive success.

Habitat

Yellow jackets are remarkably adaptable insects found across much of the Northern Hemisphere. Their geographic range spans North America, Europe, Asia, and parts of North Africa. Some species, particularly the German yellow jacket, have been introduced to other regions including Australia, New Zealand, and South America, where they’ve established invasive populations.

In North America, different species occupy distinct ranges. The Eastern yellow jacket dominates the eastern United States and Canada, while the Western yellow jacket prevails from the Pacific Coast to the Rocky Mountains. The German yellow jacket has spread throughout the continent, thriving particularly in urban and suburban areas.

These wasps favor temperate climates with distinct seasons, though they can adapt to a range of conditions. They inhabit forests, meadows, grasslands, gardens, parks, and urban areas—essentially any environment that provides suitable nesting sites and food resources. They show a particular affinity for edge habitats where forests meet clearings, as these areas offer both shelter and abundant insect prey.

Nesting site selection varies by species. Most yellow jackets nest underground, appropriating abandoned rodent burrows, hollow logs, or cavities beneath tree roots. These subterranean locations provide stable temperatures and protection from weather and predators. The workers excavate and expand the cavity to accommodate their growing paper nest, sometimes removing several liters of soil in the process.

Some species, particularly those in the Dolichovespula genus, build aerial nests attached to tree branches, building eaves, or other protected overhangs. These nests are constructed from wood fiber mixed with saliva to create a papery material—yellow jackets were making paper long before humans invented it.

The ideal habitat provides three essential resources: shelter for nesting, water for nest construction and cooling, and abundant food sources including flowering plants for nectar and populations of other insects for protein.

Diet

Yellow jackets are omnivorous opportunists with dietary needs that shift throughout the season and colony life cycle. Their feeding habits make them both beneficial predators and frustrating pests, depending on the context.

Adult yellow jackets primarily consume sugars and carbohydrates, which fuel their high-energy lifestyle. They feed on nectar from flowers, honeydew produced by aphids, tree sap, and ripe or rotting fruit. This sweet-seeking behavior explains their notorious attraction to sodas, fruit juices, and desserts at outdoor gatherings. As the season progresses and natural sugar sources diminish, they become increasingly bold in their pursuit of human food and beverages.

The protein requirements of yellow jackets center on feeding their developing larvae. Workers are voracious hunters, capturing flies, caterpillars, spiders, beetles, and other insects. They use their powerful mandibles to chew prey into a paste, which they carry back to the nest and distribute to hungry larvae. In return, the larvae produce a sugary secretion that the adult workers consume—a mutualistic exchange called trophallaxis that strengthens the social bonds within the colony.

Yellow jackets also scavenge protein from carrion, dead fish, and discarded meat. At picnics and outdoor events, they aggressively pursue hamburgers, hot dogs, and other protein-rich foods. This scavenging behavior intensifies in late summer when the colony reaches peak size and hundreds or thousands of larvae demand constant feeding.

Their foraging range extends up to 1,000 feet from the nest, though workers typically stay within a few hundred feet if resources are abundant. They are visual hunters, spotting movement and honing in on potential prey or food sources with remarkable accuracy.

Predators and Threats

Despite their formidable defenses, yellow jackets face predation from various animals that have developed strategies to overcome their stings. Bears are perhaps the most famous yellow jacket predators, raiding underground nests to consume larvae and pupae. Their thick fur and tough skin provide substantial protection against stings, and the nutritional payoff from a large nest justifies the temporary discomfort.

Skunks employ a different strategy, digging up nests at night and using their thick fur and quick reflexes to minimize stings while consuming brood and adult wasps. Raccoons, opossums, and badgers also raid nests opportunistically. Several bird species, including tanagers, kingbirds, and certain flycatchers, catch yellow jackets in flight, though they typically prefer drones and young workers with less developed venom glands.

Parasites pose significant threats to yellow jacket colonies. Several species of parasitic wasps and flies lay eggs inside yellow jacket nests, with their larvae consuming wasp larvae or parasitizing adults. Certain fungi can infect yellow jackets, altering their behavior and eventually killing them. Nematode worms can also parasitize queens, reducing their reproductive success.

Anthropogenic threats to yellow jackets are relatively minimal compared to many other species, as these adaptable insects often thrive in human-modified landscapes. However, widespread pesticide use can impact local populations, particularly when insecticides are applied indiscriminately. Climate change may alter their geographic ranges and seasonal activity patterns, potentially expanding their distribution into previously unsuitable areas.

The primary human impact is intentional nest destruction. Thousands of yellow jacket nests are eliminated annually around homes, schools, and public spaces due to safety concerns. While individual nest removal has limited impact on overall populations, it reflects the challenging relationship between humans and these beneficial but potentially dangerous insects.

Interestingly, yellow jackets in some regions face threats from invasive species. In areas where the Asian giant hornet has been introduced, these massive predators can devastate yellow jacket colonies, killing adults and raiding nests for brood.

Reproduction and Life Cycle

The yellow jacket reproductive cycle follows an annual pattern synchronized with seasonal changes. The story begins in spring when a solitary mated queen emerges from hibernation. She survived the winter by finding shelter in protected locations like hollow trees, leaf litter, or building cavities, entering a state of dormancy called diapause while all her nestmates from the previous year perished.

Upon awakening, the queen immediately begins searching for a suitable nesting site. Once she locates an appropriate cavity, she constructs the initial comb structure—a small paper nest she creates by chewing wood fibers and mixing them with saliva. This founding queen performs all tasks herself initially: building comb, laying eggs, and foraging for food. Her first batch of eggs develops into sterile female workers over approximately three to four weeks.

The queen’s eggs undergo complete metamorphosis. She deposits them in hexagonal cells, where they hatch into legless, grub-like larvae after four to five days. The queen feeds these larvae masticated insects and other proteins. After about two weeks, the larvae pupate within their cells, transforming into adults over another two weeks.

Once the first generation of workers emerges, they assume all duties except egg-laying. The queen becomes solely dedicated to reproduction, remaining inside the nest and laying eggs continuously. The colony enters an exponential growth phase, with the worker population doubling and redoubling as summer progresses.

By late summer or early fall, the colony switches its reproductive strategy. The queen begins laying unfertilized eggs that develop into males (drones) and fertilized eggs that receive special nutrition to develop into new queens rather than workers. These reproductive individuals leave the nest to mate. Males, having no other purpose, die shortly after mating. Newly mated queens gorge themselves on food to build fat reserves, then seek hibernation sites.

As temperatures drop and food becomes scarce, the colony deteriorates. The old queen’s egg-laying declines, worker production ceases, and the social order collapses. Workers become more aggressive and desperate, leading to their notorious late-season behavior. Eventually, cold weather kills all remaining workers, drones, and the old queen. Only the newly mated queens survive to restart the cycle the following spring.

The entire colony lifespan spans just one season in most temperate species, though some tropical species maintain perennial colonies. Individual workers live only four to six weeks during summer, while queens can survive up to one year from emergence to death.

Population

Yellow jackets are not globally assessed by the IUCN Red List as a single entity because the designation encompasses multiple species with varying population statuses. However, most yellow jacket species are considered common and abundant, falling under what would be classified as “Least Concern” if evaluated individually.

Population estimates for yellow jackets are challenging to determine precisely due to their widespread distribution and the annual nature of their colonies. In suitable habitats, nest density can reach impressive levels—studies have documented 10 to 50 nests per acre in favorable environments. Considering that a single mature nest may contain 1,000 to 5,000 workers at peak season, local populations can number in the hundreds of thousands within a small geographic area.

Population trends vary by species and region. Native yellow jacket species generally maintain stable populations, with natural fluctuations driven by weather patterns, resource availability, and predation pressure. Mild winters and warm, wet springs typically lead to population booms, as more queens survive hibernation and colonies develop successfully.

Invasive yellow jacket species, particularly the German yellow jacket, have shown dramatic population increases in areas where they’ve been introduced. In New Zealand and Australia, these invaders have reached pest proportions, with nests containing tens of thousands of workers—far exceeding typical colony sizes in their native range. The lack of co-evolved natural enemies and abundant food resources has enabled these explosive population growth patterns.

Climate change may influence yellow jacket populations in complex ways. Warmer winters could increase queen survival rates, potentially leading to larger populations in temperate regions. However, extreme weather events, shifts in plant flowering times, and changes in prey insect populations could negatively impact colony success.

Urban and suburban areas often support robust yellow jacket populations due to abundant nesting sites, water sources, and food availability from human activities. This proximity to people increases conflict but also demonstrates the remarkable adaptability of these insects.

Q and A:

Q. How do Yellow Jackets help the environment?

A. While yellow jackets are often known for being uninvited guests at picnics, they are actually vital “environmental custodians.” They provide natural pest control, assist with pollination, and even help clean up the environment.

Here is how yellow jackets contribute to a healthy ecosystem:

1. Natural Pest Control (The “Garden Guard”)

Yellow jackets are highly efficient predators. While the adults mostly eat sugar for energy, they hunt meat to feed their larvae.

- Target Pests: They voraciously hunt insects that humans consider garden or agricultural pests, including caterpillars, flies, beetle grubs, and spiders.

- Volume: A single yellow jacket colony can capture over 2 pounds of insects from a 2,000-square-foot garden plot in a single season. Without them, these pest populations could explode and destroy crops or ornamental plants.

2. Pollination Support

Although not as famous as honeybees, yellow jackets are “secondary pollinators.”

- Flower Visits: As adults seek out nectar and tree sap for energy, they move from flower to flower.

- Effectiveness: Because they have smoother bodies than fuzzy bees, they don’t carry as much pollen. However, they are still important, especially in late summer when they become more active in seeking out sugar sources.

3. Environmental Cleanup (Detritivores)

Yellow jackets are one of nature’s cleanup crews. They are scavengers that help decompose organic matter.

- Carrion: They will feed on dead animals, roadkill, and insects, helping to recycle nutrients back into the soil and removing decaying matter from the environment.

- Waste Management: In urban areas, they frequent trash cans, which—while annoying to humans—is part of their natural drive to scavenge and recycle waste.

4. A Critical Food Source

They occupy a middle spot in the food chain. Their nests and larvae provide a high-protein meal for several larger animals:

- Bears and Skunks: These animals will frequently dig up underground yellow jacket nests to eat the protein-rich larvae (the “brood”).

- Raccoons and Birds: Other opportunistic predators also rely on them as a seasonal food source.

Summary Table: Yellow Jackets vs. Honeybees

| Role | Yellow Jackets | Honeybees |

| Primary Diet | Insects (larvae) & Sugar (adults) | Nectar & Pollen |

| Pollination | Secondary (less efficient) | Primary (highly efficient) |

| Pest Control | Excellent (predators) | None |

| Stinger | Smooth (can sting multiple times) | Barbed (dies after one sting) |

Q. What are the purpose of Yellow Jackets?

A. In nature, nothing exists without a reason, and yellow jackets are no exception. While humans primarily interact with them as aggressive “picnic crashers,” their biological purpose is to act as environmental balancers.

They serve three primary purposes in the ecosystem:

1. Apex “Pest” Control

The most significant purpose of yellow jackets is to keep other insect populations in check. They are highly efficient hunters that feed on many of the insects we consider nuisances or crop-destroyers.1

- The Diet: While adult yellow jackets eat sugar, they hunt meat to feed their larvae.2

- The Impact: A single colony can remove over 2 pounds of insects from a small garden area in a single season.3

- Target Species: They actively hunt caterpillars, aphids, flies, beetle grubs, and spiders.4 Without yellow jackets, these populations could explode, leading to the destruction of forests and agricultural crops.

2. Nature’s Cleanup Crew (Sanitation)

Yellow jackets are scavengers and detritivores.5 Their purpose is to help recycle nutrients back into the ecosystem by breaking down organic matter.

- Scavenging: They feed on dead animals (carrion), fallen fruit, and decaying organic waste.6

- The Result: By consuming these items, they help speed up the process of decomposition and prevent the buildup of rotting material that could spread disease.

3. A Link in the Food Chain

Yellow jackets provide a critical source of high-protein food for other wildlife.7 Despite their stingers, they are a preferred meal for several “wasp-specialist” predators:

- Bears and Skunks: These animals will dig up entire underground nests to eat the protein-rich larvae (the “brood”).8

- Birds and Reptiles: Various bird species and lizards rely on catching adult yellow jackets as a staple part of their diet.

Summary of Roles

| Role | Environmental Function |

| Predator | Naturally suppresses populations of garden and crop pests. |

| Pollinator | Provides backup pollination services when visiting flowers for nectar. |

| Scavenger | Cleans up dead insects and animal remains from the forest floor. |

| Prey | Acts as a vital protein source for mammals and birds. |

Note on Behavior: Their “purpose” shifts by the season. In the spring and summer, they are predators focused on gathering protein (meat) for their young.9 In late autumn, their purpose shifts to survival, as they search for sugar to fuel the new queens for winter—which is usually when they become most aggressive toward humans and our soda cans.

Q. Are Yellow Jackets aggressive to humans?

A.Yes, yellow jackets are among the most aggressive and territorial stinging insects. Unlike honeybees, which are generally docile unless their hive is attacked, yellow jackets can be provoked by very minor disturbances.

Here is a breakdown of why they are so aggressive and what triggers them:

1. Fierce Territorial Defense

Yellow jackets are social insects that will vigorously defend their colony.

- Vibration Sensitivity: Many yellow jackets nest in the ground. They are extremely sensitive to vibrations. Walking too close to a nest or running a lawnmower or weed whacker nearby can trigger a “swarm” response where hundreds of wasps emerge to attack.

- Alarm Pheromones: When a yellow jacket stings or is crushed, it releases a chemical scent (pheromone) that signals every other wasp in the vicinity to join the attack. This is why one sting often quickly leads to many.

2. Multi-Sting Capability

- Smooth Stingers: Unlike honeybees, which have barbed stingers that pull out (killing the bee), yellow jackets have smooth stingers. This allows a single individual to sting you repeatedly without being harmed.

- Biting and Stinging: They will often use their mandibles (jaws) to bite and “anchor” themselves to your skin or clothing so they can pump in more venom through multiple stings.

3. The “Hangry” Phase (Late Summer/Fall)

Yellow jackets become significantly more aggressive as the year progresses.

- Dietary Shift: In the spring, they focus on protein (insects) to feed their larvae. By late summer, the larvae are gone, and the adults are “out of work.” They develop a desperate craving for sugar.

- Proximity to Humans: This sugar craving brings them to trash cans, soda cans, and picnics. Because they are hungry and competing for scarce resources, they are much more likely to be “pushy” and sting if you try to swat them away.

4. Persistence

If they decide to attack, they are famously persistent. They have been known to chase people for long distances. Unlike some other insects, they won’t necessarily stop if you run; they will continue the pursuit until you are well away from their territory or you find shelter in a car or building.

How to Stay Safe

Wear Neutral Colors: Bright floral patterns or very dark colors (which look like predators) can sometimes attract or agitate them.

Don’t Swat: If one lands on you, try to remain still or gently brush it off. Rapid movements like swatting are seen as a threat.

Check Your Cans: In Florida, always check the rim of your soda or beer can before taking a sip, as they often crawl inside.

Q. Is a Yellow Jacket an insect?

A. Yes, a yellow jacket is most definitely an insect.

Specifically, it belongs to a group of social wasps. To qualify as an insect, an animal must meet several biological criteria, all of which the yellow jacket fits perfectly:

Why a Yellow Jacket is an Insect

- Three Body Segments: Like all insects, their body is divided into a head, a thorax (the middle section), and an abdomen (the striped back section).

- Six Legs: They have exactly three pairs of jointed legs attached to the thorax.

- Exoskeleton: They don’t have bones; instead, they have a hard outer shell made of chitin that protects their internal organs.

- Antennae: They have one pair of prominent antennae used for smelling and sensing vibrations.4

- Wings: Most insects have wings, and yellow jackets have two pairs of membranous wings.

Scientific Classification

In the scientific world, they are classified under the class Insecta. Here is their full “address” in the tree of life:

| Rank | Classification |

| Kingdom | Animalia (Animals) |

| Phylum | Arthropoda (Arthropods) |

| Class | Insecta (Insects) |

| Order | Hymenoptera (Ants, Bees, and Wasps) |

| Family | Vespidae (Wasps) |

| Genus | Vespula or Dolichovespula |

Common Misconceptions

People often mistake yellow jackets for bees because of their yellow and black stripes. However, while both are insects, they are different:

Yellow jackets have smooth, shiny bodies and are predatory hunters.

Bees are usually fuzzy (to collect pollen) and are generally less aggressive.

Q. Do Yellow Jackets attack unprovoked?

A. Technically, “unprovoked” is a matter of perspective. From a human perspective, it often feels like they attack for no reason. From a yellow jacket’s perspective, they are almost always responding to a perceived threat—though that “threat” can be something as small as you walking 10 feet away from their hidden nest.

Here is the breakdown of why they might seem to attack unprovoked:

1. Vibration Sensitivity (The Most Common Trap)

Yellow jackets are extremely sensitive to ground vibrations. Because they often nest underground, they can sense a “threat” long before you even see the nest.

- The “Invisible” Trigger: Walking, running, or especially mowing the lawn near a nest can feel like an earthquake to the colony.

- The Response: They will swarm and attack whoever or whatever is causing the vibration, even if you are several feet away and haven’t actually touched the nest.

2. Behavioral Shifts (The “Hangry” Phase)

In late summer and fall, yellow jackets undergo a biological shift that makes them appear more “unprovoked” in their aggression.

- Food Scarcity: As their natural food sources (insects) disappear, they become desperate for sugar to fuel the next generation of queens.

- Irritability: During this time, they are often described as “drunk” or “hangry.” They are much more likely to sting someone just for being near a food source (like a soda can or trash bin) because they are in a high-stress survival mode.

3. Alarm Pheromones

If you swat at a single yellow jacket and happen to hit it (or worse, crush it), it releases a chemical alarm pheromone.5

- The “Call to Arms”: This scent tells every other yellow jacket in the area that there is a battle happening. Other wasps will fly in from downwind and attack you immediately, even if they weren’t even looking at you a moment before.

4. Facial Targeting and Pursuit

Yellow jackets are one of the few insects that will actually chase you.

- The Chase: If you run, they may pursue you for 50 yards or more.

- Targeting: They are biologically programmed to target the face and head of “predators” (which, to them, includes you), which makes the attack feel much more personal and aggressive.

Comparison: Are they more aggressive than others?

| Insect | Aggression Level | Typical Trigger |

| Honeybee | Low | Direct physical contact or nest destruction. |

| Paper Wasp | Medium | Usually only if you are within 1–2 feet of their nest. |

| Yellow Jacket | High | Vibrations, scents, or just being “in the way” of food. |

In short: While they rarely sting if you are standing perfectly still in an open field, their “defensive zone” is so large and their triggers are so sensitive that their attacks frequently feel unprovoked to humans.

Conclusion

The yellow jacket stands as a testament to the power of social cooperation and evolutionary adaptation. While their painful stings and aggressive defense of nesting sites have earned them a fearsome reputation, these remarkable insects fulfill essential ecological roles as predators of pest insects and as scavengers that help decompose organic matter. Their sophisticated societies, impressive hunting abilities, and remarkable behavioral flexibility deserve our respect and fascination.

Understanding yellow jackets—their biology, behavior, and ecological importance—can transform our relationship with them from one of simple antagonism to grudging appreciation. They are not merely pests to be eradicated, but complex creatures navigating their world with the same determination to survive and reproduce that drives all life on Earth.

As we continue to modify landscapes and expand human settlements, yellow jackets will undoubtedly remain our neighbors, testing our tolerance and reminding us that we share this planet with countless other species pursuing their own evolutionary imperatives. Perhaps the next time a yellow jacket investigates your picnic, you might pause before swatting—and recognize it as a skilled hunter, devoted colony member, and evolutionary success story millions of years in the making.

Scientific Name: Vespula spp. and Dolichovespula spp.

Diet Type: Omnivore (adults consume sugars and carbohydrates; larvae are fed proteins from insects and carrion)

Size: Workers: 10-16 mm (0.4-0.6 inches); Queens: up to 20 mm (0.8 inches)

Weight: 70-130 milligrams per worker

Region Found: Northern Hemisphere including North America, Europe, Asia, and North Africa; introduced populations in Australia, New Zealand, and South America