Slicing through tropical waters with lightning speed, the barracuda is one of the ocean’s most formidable predators. With a mouth full of razor-sharp teeth, a streamlined body built for explosive acceleration, and an intimidating stare that seems to pierce straight through you, this fish commands both respect and fascination. Often feared by swimmers and revered by anglers, the barracuda represents the perfect marriage of predatory efficiency and evolutionary refinement. These fearsome hunters have patrolled the world’s warm seas for millions of years, adapting to become one of the most successful ambush predators in marine ecosystems. Understanding the barracuda offers us a window into the complex dynamics of ocean food webs and the remarkable adaptations that allow certain species to dominate their ecological niches.

Facts

- Barracudas can swim at speeds exceeding 35 miles per hour in short bursts, making them one of the fastest fish in the ocean.

- Their lower jaw protrudes beyond the upper jaw, and their teeth are so sharp and numerous that they cannot fully close their mouths.

- Barracudas have been known to live for more than 14 years in the wild, with some species potentially reaching 20 years.

- Young barracudas are sometimes found in brackish estuaries and mangrove forests, while adults prefer deeper open waters and coral reefs.

- These fish rely primarily on sight rather than smell to hunt, possessing exceptionally keen eyesight that helps them detect the slightest movements.

- Barracudas occasionally suffer from ciguatera toxin accumulation by eating smaller fish that feed on toxic algae, making large specimens potentially dangerous for human consumption.

- Despite their fearsome reputation, unprovoked barracuda attacks on humans are extremely rare, with most incidents resulting from the fish mistaking shiny objects for prey.

Species

Kingdom: Animalia

Phylum: Chordata

Class: Actinopterygii (ray-finned fishes)

Order: Carangiformes

Family: Sphyraenidae

Genus: Sphyraena

Species: Multiple species, with Sphyraena barracuda being the most well-known

The genus Sphyraena contains approximately 28 recognized species of barracuda, distributed throughout tropical and subtropical oceans worldwide. The great barracuda (Sphyraena barracuda) is the largest and most infamous species, known for its size and aggressive hunting behavior. Other notable species include the Pacific barracuda (Sphyraena argentea), which inhabits the eastern Pacific Ocean, and the European barracuda (Sphyraena sphyraena), found in the Mediterranean Sea and eastern Atlantic. The pickhandle barracuda (Sphyraena jello) is distinguished by dark vertical bars along its body, while the yellowtail barracuda (Sphyraena flavicauda) features a distinctive yellow tail fin. Each species has adapted to its particular geographic range and ecological niche, though all share the characteristic elongated body, powerful jaws, and predatory lifestyle that define the barracuda family.

Appearance

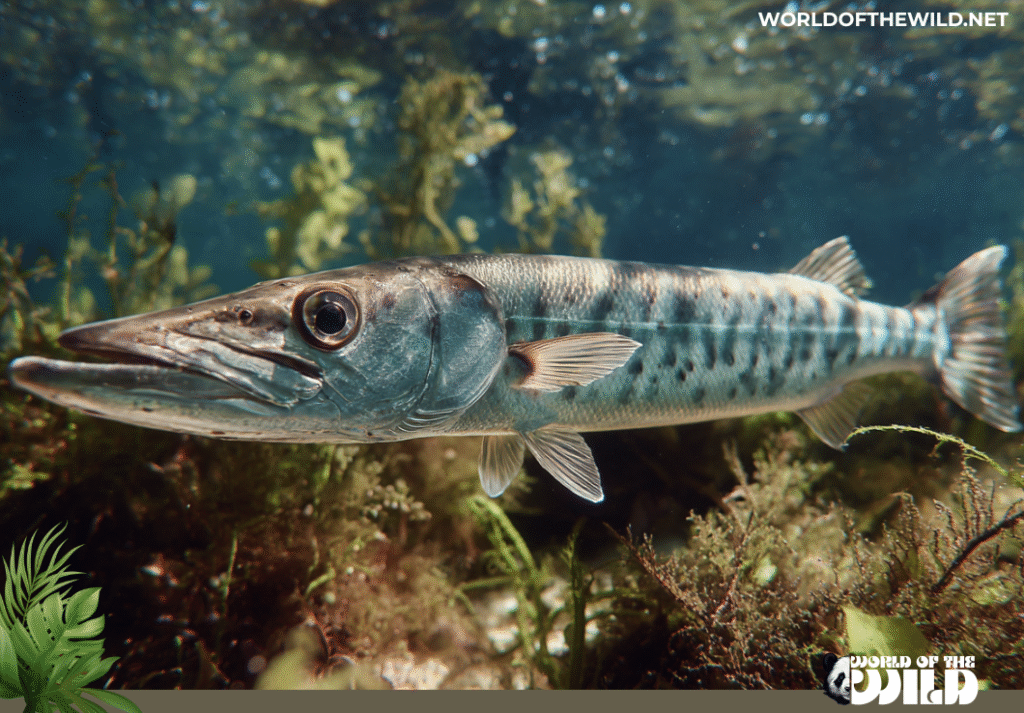

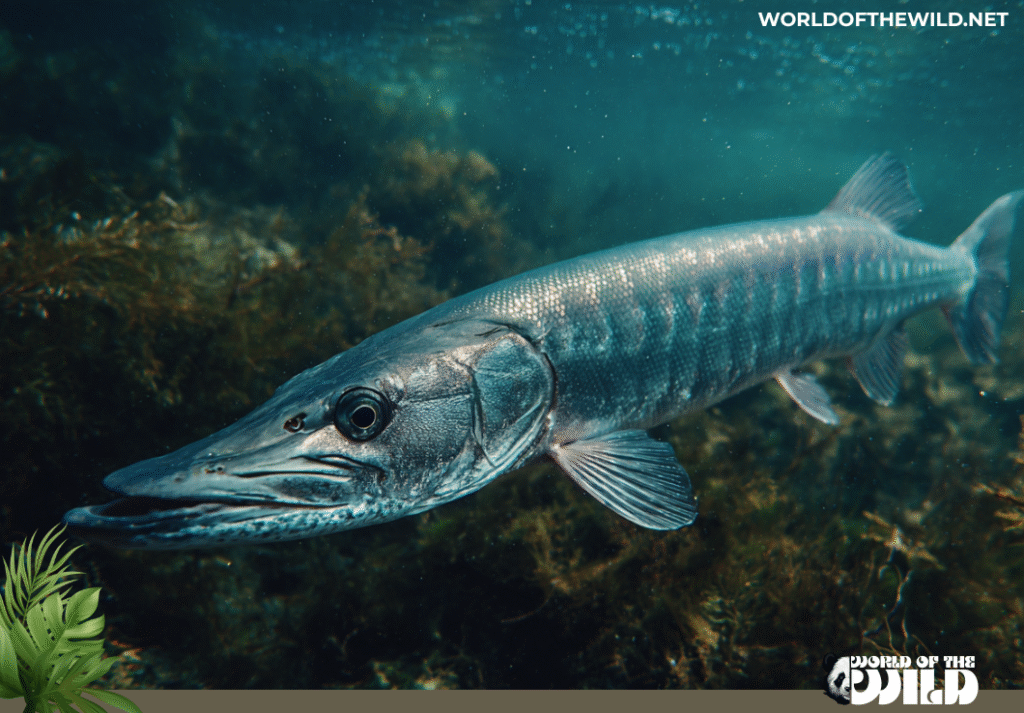

The barracuda’s appearance is nothing short of intimidating. These fish possess an elongated, torpedo-shaped body covered in small, smooth scales that create a sleek, hydrodynamic profile. Their coloration typically features a silver or gray body with a white or yellowish belly, though some species display darker backs ranging from bluish-gray to greenish-brown. This counter-shading provides excellent camouflage, making them difficult to spot from both above and below in the water column.

The most striking feature of any barracuda is undoubtedly its mouth. Lined with two sets of razor-sharp teeth, the outer row consists of small, pointed teeth designed for gripping, while the inner row features larger, fang-like teeth meant for tearing and slashing. These teeth are so prominent that they remain visible even when the fish’s mouth is closed. The lower jaw extends slightly beyond the upper jaw, creating an underbite that adds to the fish’s menacing appearance.

Size varies considerably among species. The great barracuda can reach lengths of up to six feet and weigh as much as 110 pounds, though specimens of four to five feet weighing 20 to 50 pounds are more common. Smaller species like the Pacific barracuda typically reach lengths of three to four feet. The barracuda’s large eyes are positioned far forward on the head, providing binocular vision that aids in judging distances when striking at prey. Two dorsal fins sit atop the body—the first short and spiny, the second soft-rayed and positioned near the tail—while the caudal fin is deeply forked, a design feature that contributes to their explosive swimming speed.

Behavior

Barracudas exhibit fascinating behavioral patterns that reflect their role as apex predators in many reef ecosystems. Adult great barracudas are typically solitary hunters, patrolling their territories with a slow, deliberate swimming pattern that can erupt into startling bursts of speed when prey is detected. They often hover motionless in the water, using their excellent eyesight to scan for potential meals, then accelerate with remarkable quickness to strike.

Interestingly, some species display different social structures depending on their life stage and species type. Juvenile barracudas and some smaller species form large schools that can number in the hundreds. These schools move in coordinated formations, creating swirling, tornado-like patterns that are spectacular to observe. The schooling behavior likely provides protection from larger predators and may also facilitate hunting by corralling prey fish into tight groups.

Barracudas are visual predators with exceptional eyesight adapted for detecting movement and the flash of light reflecting off fish scales. This adaptation makes them particularly attracted to shiny, reflective objects, which explains why they occasionally investigate divers wearing jewelry or watches. Their hunting strategy typically involves stealth and ambush rather than prolonged pursuit. A barracuda will position itself strategically, often near structural features like coral heads or rocky outcrops, waiting for unsuspecting prey to venture within striking range.

Communication among barracudas appears to be primarily visual, with body language and positioning conveying information between individuals. When threatened or during territorial disputes, barracudas may display aggressive posturing, including opening their mouths wide to showcase their impressive dentition. They are intelligent fish capable of learning and adapting their hunting strategies based on experience and environmental conditions.

Evolution

The evolutionary history of barracudas stretches back millions of years, though the fossil record for the family Sphyraenidae remains somewhat sparse compared to other fish families. The earliest recognizable barracuda fossils date from the Eocene epoch, approximately 50 million years ago, indicating that these fish have maintained their basic body plan and predatory lifestyle for an extraordinarily long time.

Barracudas belong to the order Carangiformes, which also includes jacks, pompanos, and amberjacks. This order emerged during the late Cretaceous period, though barracudas themselves likely diverged later, during the Paleogene period as ocean conditions changed following the mass extinction event that ended the age of dinosaurs. The warming of ocean waters and the proliferation of coral reefs created new ecological niches that barracudas exploited with their speed and predatory adaptations.

The evolution of the barracuda’s distinctive morphology represents a masterclass in adaptive design. The elongated body plan evolved to reduce drag and maximize swimming efficiency, allowing for the rapid acceleration necessary to catch fast-moving prey. The development of their formidable dentition reflects a specialization for capturing and consuming other fish, with the dual-row tooth arrangement being particularly effective at preventing prey from escaping once caught.

Molecular studies suggest that the various species of barracuda diversified relatively recently in evolutionary terms, possibly within the last 10 to 15 million years, as populations became isolated in different ocean basins. This diversification occurred during a period of significant oceanographic change, including the closure of the Tethys Sea and the formation of the Isthmus of Panama, events that created barriers to gene flow and allowed distinct species to evolve in different regions.

Habitat

Barracudas are predominantly creatures of warm, tropical and subtropical waters, inhabiting oceans worldwide within a band roughly extending from 30 degrees north to 30 degrees south latitude. The great barracuda, being the most widespread species, ranges throughout the western Atlantic Ocean from Massachusetts to Brazil, including the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean Sea, as well as the eastern Atlantic from Sierra Leone to the Mediterranean Sea, and into the Indo-Pacific region.

These fish show a strong preference for coastal waters, particularly around coral reefs, seagrass beds, and mangrove forests. Adults typically patrol reef edges and drop-offs where the continental shelf meets deeper water, positioning themselves at depths ranging from just below the surface to about 100 feet, though they occasionally venture deeper. The structural complexity of coral reefs provides ideal ambush points for hunting, while the abundance of prey fish in these ecosystems ensures a reliable food supply.

Juvenile barracudas often occupy different habitats than adults, utilizing shallow, protected environments such as mangrove estuaries, lagoons, and seagrass meadows. These nursery areas offer protection from larger predators while providing ample opportunities to hunt small fish and invertebrates. As barracudas mature, they gradually move into deeper, more open waters.

Water temperature plays a crucial role in barracuda distribution. They thrive in waters ranging from 74 to 82 degrees Fahrenheit, though they can tolerate slight variations. During seasonal temperature changes, some populations undertake limited migrations, moving to warmer waters or deeper depths to maintain optimal conditions. The Pacific barracuda, for instance, migrates northward along the California coast during summer months when water temperatures rise, then returns south as waters cool in autumn.

Diet

Barracudas are strict carnivores, sitting high on the marine food chain as voracious predators of smaller fish. Their diet consists primarily of various fish species including anchovies, sardines, mullet, groupers, snappers, grunts, and even smaller barracudas. They will also consume squid and occasionally larger crustaceans when the opportunity arises, though fish make up the vast majority of their diet.

The hunting strategy of a barracuda is built around sudden, overwhelming force. Using their exceptional eyesight, they identify potential prey from distances of up to 70 feet. Once a target is selected, the barracuda employs one of two primary hunting methods. In open water, they may accelerate rapidly toward their prey, reaching their target in a fraction of a second and striking with devastating precision. Their attack speed creates a shockwave that can stun smaller fish, making them easier to capture.

Alternatively, barracudas are masters of the ambush. They position themselves alongside coral formations, rocks, or even in open water, remaining nearly motionless as they wait for prey to wander within striking distance. Their counter-shaded coloration makes them difficult for prey fish to detect until it’s too late. When the moment is right, they explode forward in a burst of speed, opening their large jaws to seize their victim.

The barracuda’s teeth are perfectly designed for their predatory lifestyle. The outer row of small, sharp teeth pierce and grip the prey, preventing escape, while the larger inner fangs cut and tear flesh. When attacking larger prey, a barracuda may not swallow its catch whole but instead bite chunks from its victim. They typically swallow smaller prey head-first, using the fish’s streamlined shape to ease swallowing and prevent scales or spines from catching in the throat.

Barracudas are opportunistic feeders with hearty appetites, often consuming prey up to half their own body length. They hunt primarily during daylight hours when their visual advantage is greatest, though they may continue feeding during twilight periods.

Predators and Threats

Despite their position near the top of the marine food chain, barracudas face threats from both natural predators and human activities. Larger marine predators view barracudas as potential meals, particularly when the barracudas are young or of smaller species. Sharks, including tiger sharks, bull sharks, and great hammerheads, readily prey upon barracudas. Large groupers also pose a threat, especially to juvenile barracudas occupying reef environments. Dolphins have been observed hunting barracudas, using their superior intelligence and echolocation to overcome the fish’s speed advantage. In some regions, killer whales include barracudas as part of their varied diet.

Human-caused threats present increasingly significant challenges to barracuda populations. Overfishing represents the most direct threat, as barracudas are targeted both commercially and recreationally. While they are prized game fish due to their size and fighting ability, concerns about ciguatera toxin accumulation have reduced commercial fishing pressure in some areas, though this provides only partial protection.

Habitat degradation poses an equally serious problem. Coral reef destruction through climate change, ocean acidification, pollution, and physical damage eliminates critical hunting grounds and reduces prey availability. The loss of mangrove forests and seagrass beds destroys vital nursery habitats where juvenile barracudas grow and develop. Coastal development, including marina construction, dredging, and pollution from agricultural runoff, degrades water quality and eliminates the complex habitat structures barracudas require.

Climate change presents multifaceted threats to barracuda populations. Rising ocean temperatures may expand their range in some areas while making traditional habitats inhospitable in others. Changes in ocean currents and water chemistry affect prey fish populations, potentially disrupting the food web that barracudas depend upon. More frequent and severe storm events can damage critical reef and coastal habitats.

Reproduction and Life Cycle

Barracuda reproduction follows patterns typical of many reef-associated fish species, though specific details vary among the different species. Sexual maturity is reached at different ages depending on the species and environmental conditions, but great barracudas typically mature between two and four years of age, at lengths of approximately two to three feet.

Spawning occurs in offshore waters, often near reef edges or in open ocean areas away from coastal regions. The timing of reproduction is influenced by water temperature and varies geographically. In tropical regions, barracudas may spawn year-round with peak activity during warmer months, while populations in subtropical areas typically have more defined spawning seasons, usually occurring in spring and early summer.

Mating behavior involves aggregations of adult barracudas congregating in specific spawning areas. Males and females engage in courtship displays, though the specifics are not as well documented as in some other species. Fertilization is external, with females releasing eggs into the water column while males simultaneously release sperm. A large female can produce upwards of 300,000 eggs during a single spawning event, though not all will survive to adulthood.

The eggs are pelagic, meaning they drift in ocean currents, developing as they travel. Hatching occurs within 24 to 48 hours depending on water temperature. The larvae are tiny, transparent, and completely helpless, drifting with plankton while feeding on microscopic organisms. This larval stage is extremely vulnerable, with predation rates exceeding 99 percent.

As larvae develop into juveniles over several weeks, they begin to resemble adult barracudas, though they remain translucent. Young barracudas instinctively seek out protected coastal habitats like mangrove forests and estuaries, where they find shelter among roots and vegetation. Here they feed on small fish and invertebrates, growing rapidly if conditions are favorable.

Growth rates vary by species and environmental factors, but barracudas are relatively fast-growing fish. Juveniles may gain several inches per month during their first year. As they mature, growth slows considerably. Adult barracudas can live for 10 to 15 years in most species, with larger species like the great barracuda potentially reaching ages of 15 to 20 years or more under optimal conditions.

Population

The conservation status of barracudas varies depending on the species, but most are currently listed as “Least Concern” by the International Union for Conservation of Nature. This designation indicates that, overall, barracuda populations remain relatively stable and widespread, without immediate risk of extinction. However, this status masks regional variations and concerning trends in specific areas.

Estimating precise global population numbers for barracudas is challenging due to their wide distribution and the difficulty of conducting comprehensive surveys in marine environments. Populations are generally considered healthy in protected marine areas and regions with effective fisheries management, but significant declines have been documented in heavily fished areas and regions experiencing severe habitat degradation.

The great barracuda, being the most widely distributed and studied species, appears to maintain stable populations across much of its range. However, localized depletions have occurred in areas with high fishing pressure, particularly in the Caribbean and parts of the western Atlantic. Some Caribbean islands have reported noticeable decreases in both the number and average size of barracudas encountered on reefs, suggesting overfishing of larger, older individuals.

Population trends for most barracuda species are difficult to assess due to limited long-term monitoring data. Unlike some commercially important species that are carefully tracked, recreational catch limits and commercial fishing records for barracudas are often incomplete or inconsistent. This data gap makes it challenging to identify population problems before they become severe.

Factors supporting relatively stable populations include the barracuda’s wide geographic range, adaptability to various habitat types, high reproductive output, and the fact that ciguatera concerns limit consumption in many areas. Additionally, their role as top predators means they naturally occur at lower population densities than prey species, and their populations can be sustained with relatively modest reproductive success.

Conclusion

The barracuda stands as a testament to millions of years of evolutionary refinement, a predator perfectly adapted to life in tropical and subtropical seas. From their streamlined, torpedo-shaped bodies to their intimidating arrays of razor-sharp teeth, every aspect of their biology speaks to their role as efficient hunters. These remarkable fish maintain crucial ecological balance in reef ecosystems, controlling prey fish populations and contributing to the complex web of interactions that keeps marine communities healthy and diverse.

While current conservation assessments suggest most barracuda populations remain stable, we cannot afford complacency. The combined pressures of overfishing, habitat destruction, and climate change threaten the ocean ecosystems these magnificent predators call home. Protecting coral reefs, mangrove forests, and seagrass beds isn’t just about saving beautiful landscapes—it’s about preserving the intricate habitats that support barracudas throughout their life cycles. By supporting marine protected areas, practicing sustainable fishing, and taking action on climate change, we can ensure that future generations will continue to witness the silver flash of a barracuda hunting through crystal-clear tropical waters, a sight that has captivated ocean observers for millennia.

Scientific Name: Sphyraena barracuda (great barracuda) and related species in genus Sphyraena

Diet Type: Carnivore

Size: Up to 6 feet (1.8 meters); commonly 3-5 feet (0.9-1.5 meters)

Weight: Up to 110 pounds (50 kg); commonly 20-50 pounds (9-23 kg)

Region Found: Tropical and subtropical waters worldwide, including western Atlantic, Caribbean, Gulf of Mexico, Indo-Pacific, and Mediterranean Sea