Few creatures inspire such visceral fear from a single word as the piranha. Hollywood has painted these fish as aquatic demons capable of stripping a cow to its skeleton in seconds, while horror stories from the Amazon speak of swimmers disappearing into crimson-frothed waters. Yet the truth about piranhas is far more complex—and fascinating—than their fearsome reputation suggests. These remarkable fish are sophisticated social creatures with surprisingly diverse diets, intricate behaviors, and a crucial role in South American river ecosystems. Far from being mindless killing machines, piranhas represent one of nature’s most successful evolutionary experiments in tropical waters, combining razor-sharp teeth with unexpected intelligence and even moments of surprising timidity. Understanding the real piranha means peeling away decades of myth to reveal an animal that is simultaneously more dangerous and more vulnerable than most people imagine.

Facts

- They bark like dogs: Piranhas produce at least three distinct vocalizations by rapidly contracting their swim bladder muscles, including warning barks, threatening croaks, and aggressive drum-like sounds during confrontations with rivals or predators.

- Vegetarian relatives exist: Despite their carnivorous reputation, piranhas have close cousins called pacus that primarily eat fruits and nuts, and even some piranha species consume significant amounts of plant matter, particularly seeds and aquatic vegetation.

- They’ve survived largely unchanged for 25 million years: Fossil evidence shows that piranha-like fish with similar dental structures existed in the Miocene epoch, making them one of the most successful and evolutionarily stable fish groups in South America.

- Their teeth are self-sharpening: Piranha teeth are arranged so that upper and lower jaws interlock perfectly, causing them to sharpen against each other with every bite, maintaining their legendary razor edge throughout the fish’s life.

- They can live in small home aquariums: Despite their fierce image, piranhas are popular in the aquarium trade and can become surprisingly docile pets, though they’re illegal to own in many jurisdictions due to ecological concerns.

- Theodore Roosevelt exaggerated their danger: The former president witnessed a staged piranha feeding frenzy during a 1913 expedition where locals had starved the fish for days, then his sensationalized account in “Through the Brazilian Wilderness” cemented the piranha’s terrifying reputation in Western culture.

- They’re more afraid of you than you are of them: Piranhas are actually skittish fish that typically flee from large animals, and most human “attacks” occur when people accidentally step on them in murky water or when the fish are trapped in drying pools during drought conditions.

Species

Kingdom: Animalia

Phylum: Chordata

Class: Actinopterygii (ray-finned fishes)

Order: Characiformes

Family: Serrasalmidae

Genus: Pygocentrus (red-bellied piranhas) and Serrasalmus (most other species)

Species: Approximately 30-60 species, depending on taxonomic classification

The term “piranha” doesn’t refer to a single species but rather a group of freshwater fish within the Serrasalmidae family. Taxonomists continue to debate the exact number of species, as new ones are occasionally discovered and others are reclassified. The most well-known and studied species include the red-bellied piranha (Pygocentrus nattereri), which is responsible for most of the piranha’s fearsome reputation. Other notable species include the black piranha (Serrasalmus rhombeus), one of the largest and most solitary species; the wimple piranha (Catoprion mento), which feeds primarily on fish scales; and the San Francisco piranha (Pygocentrus piraya), the largest species that can exceed 50 centimeters in length.

The genus Pygocentrus contains the most social and aggressive species, including P. nattereri, P. piraya, and P. cariba. The genus Serrasalmus includes more than 20 species that tend to be more solitary and opportunistic. Interestingly, piranhas share their family with the pacu, a mostly herbivorous relative with human-like teeth adapted for crushing nuts. This close relationship highlights the diverse evolutionary paths within Serrasalmidae, from plant-eaters to apex predators.

Appearance

Piranhas are laterally compressed fish with deep, muscular bodies designed for quick bursts of speed in their river habitats. Most species range from 15 to 25 centimeters in length, though the largest specimens of certain species can reach up to 50 centimeters. Their bodies are typically silver or gray with varying degrees of metallic scales that reflect light, helping them blend into the dappled shadows of river waters. Many species display brilliant coloration, particularly during breeding season, with vivid orange or red underbellies, throats, and fins—a characteristic that gives the red-bellied piranha its name.

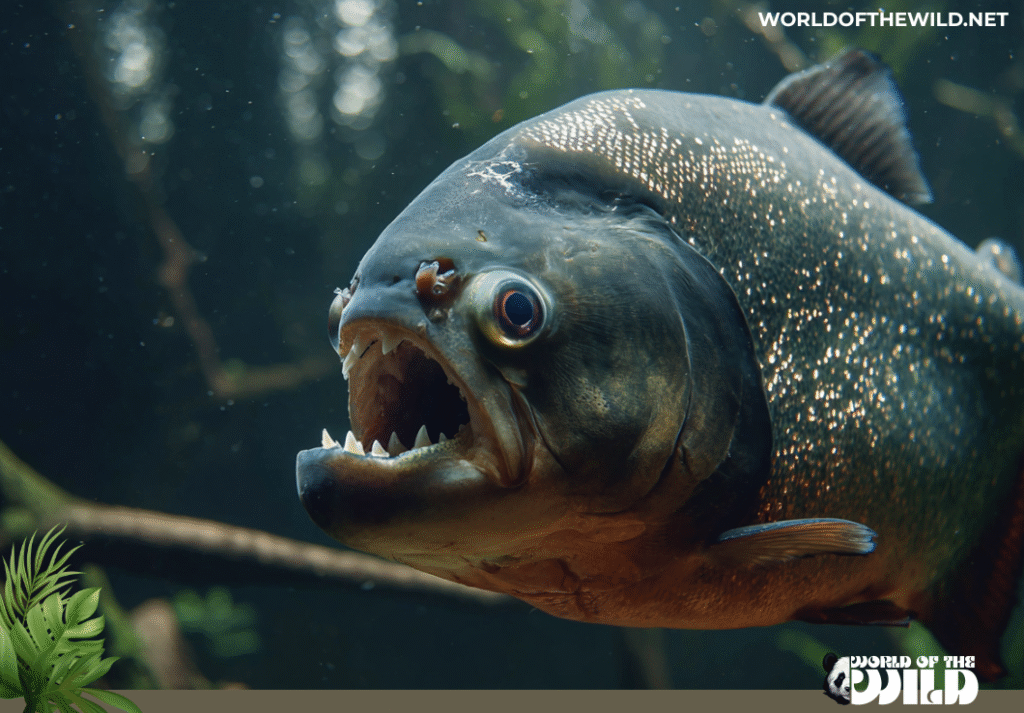

The piranha’s most distinctive feature is undoubtedly its jaw structure and dentition. Their mouths contain a single row of triangular, interlocking teeth on both upper and lower jaws, each tooth measuring up to 4 millimeters in length. These teeth are exceptionally sharp, designed to slice rather than tear, and are replaced throughout the fish’s lifetime. The powerful jaw muscles can generate a bite force of approximately 72 pounds per square inch relative to body size—one of the strongest bites among bony fish and comparable to many large predators.

Piranhas possess large, prominently positioned eyes that provide excellent vision in the often murky waters they inhabit. Their eyes contain a reflective layer called the tapetum lucidum, similar to cats, which enhances their ability to see in low-light conditions. The caudal fin is deeply forked, providing powerful propulsion, while the adipose fin—a small, fleshy fin between the dorsal fin and tail—is characteristic of characiform fish. Coloration varies significantly among species: black piranhas are dark gray to black, while red-bellied piranhas display the characteristic bright red ventral region that intensifies with age and during breeding.

Behavior

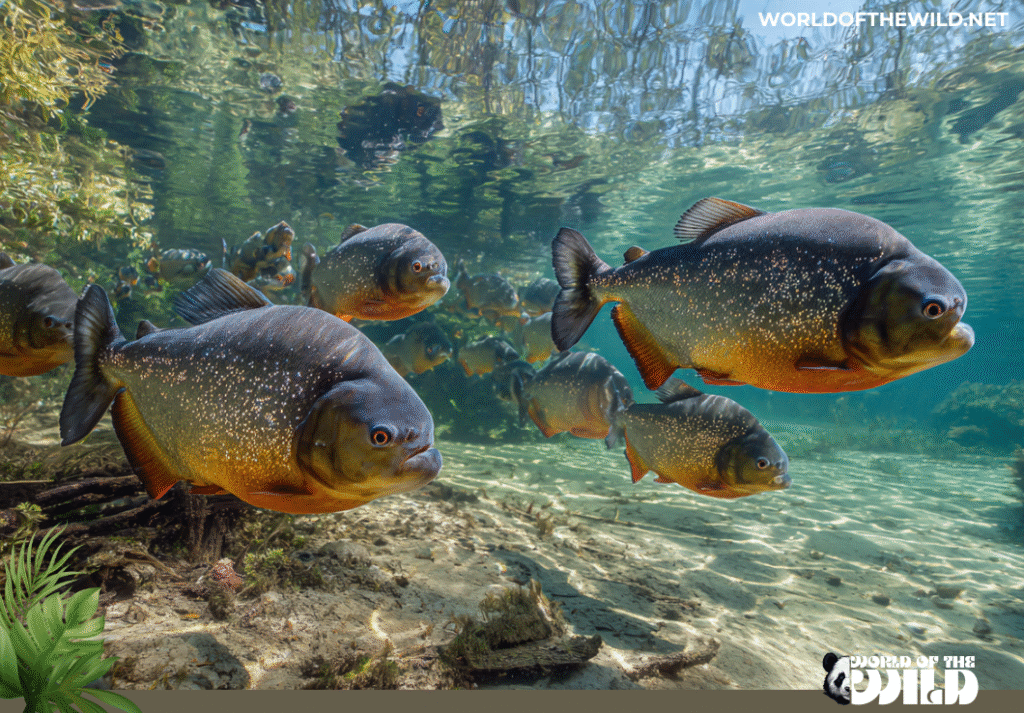

Contrary to popular belief, piranhas spend much of their time behaving like typical schooling fish, swimming in coordinated groups that can number from a few dozen to several hundred individuals. This schooling behavior is primarily defensive rather than offensive—piranhas aggregate to protect themselves from larger predators like caimans, river dolphins, and giant otters. Within these schools, piranhas establish subtle hierarchies based on size and aggression, though they lack the complex social structures found in some other fish species.

Piranhas are most active during daylight hours, particularly during dawn and dusk when they hunt most intensively. They employ a hunting strategy known as “lurk and lunge,” remaining relatively motionless while waiting for prey to approach, then attacking with explosive speed. During feeding on larger prey, multiple individuals may attack simultaneously in what appears to be a coordinated frenzy, though this behavior is actually opportunistic rather than truly cooperative. Each fish attempts to tear away pieces as quickly as possible before competitors arrive, creating the violent feeding spectacle that has captivated and terrified observers.

Communication among piranhas involves sophisticated acoustic signaling. They produce sounds by rapidly contracting muscles around their swim bladder, creating different vocalizations for various situations. Aggressive encounters produce drumming sounds, while threatening displays generate croaking noises, and warning calls resemble barks. These vocalizations help maintain spacing within schools and signal dominance during territorial disputes. Piranhas also exhibit interesting display behaviors, including jaw snapping, circular swimming patterns, and brief physical confrontations that rarely result in serious injury among school members.

Intelligence in piranhas manifests in several ways. They demonstrate learning ability in laboratory settings, can distinguish between individual predators based on threat level, and adjust their behavior based on water conditions and food availability. During the dry season when water levels drop and food becomes scarce, piranhas become more aggressive and may attack larger animals, including humans, particularly if those animals are wounded or thrashing in distress. However, during the wet season when food is abundant and waters are high, piranhas are remarkably timid and will flee from any large disturbance.

Evolution

The evolutionary story of piranhas begins approximately 25 million years ago during the Miocene epoch when South America was experiencing dramatic geological changes. The uplift of the Andes Mountains transformed the region’s drainage patterns, creating the complex river systems that would become the Amazon Basin. These changing waterways provided new ecological niches that ancestral characiform fish began to exploit.

Piranhas evolved from herbivorous or omnivorous ancestors within the Serrasalmidae family, which also includes the modern pacu. The transition from plant-eating to carnivory represents a remarkable evolutionary adaptation to new feeding opportunities. Fossil evidence from the Miocene shows fish with piranha-like dental structures, suggesting that the characteristic triangular, interlocking teeth evolved relatively quickly in geological terms. This rapid evolution was likely driven by competition for food resources and the abundance of fish prey in the expanding river systems.

The development of the piranha’s distinctive bite required several coordinated evolutionary changes. The jaw muscles became more powerful through selective pressure favoring individuals capable of taking larger bites from prey. The teeth evolved to be self-sharpening through precise interlocking, eliminating the need for the constant tooth replacement seen in sharks and other predators. The skull structure changed to accommodate the massive jaw muscles, creating the deep-bodied, powerful-jawed morphology we see today.

Molecular studies suggest that the modern piranha genera diverged approximately 9 million years ago, coinciding with further changes in South American river systems. The split between Pygocentrus (the more social, aggressive species) and Serrasalmus (typically more solitary species) likely reflects adaptation to different ecological niches and feeding strategies. Some researchers hypothesize that the social hunting behavior of Pygocentrus species evolved as a strategy to tackle larger prey that solitary individuals couldn’t handle alone.

The geographic isolation of different river systems during various periods of the Pleistocene ice ages led to speciation events, creating the diversity of piranha species we observe today. Different populations adapted to local conditions, prey availability, and predator pressures, resulting in variations in size, coloration, social behavior, and dietary preferences across species and populations.

Habitat

Piranhas are exclusively freshwater fish endemic to South America, with their range extending from the Orinoco River basin in Venezuela through the Amazon River system in Brazil, Peru, Ecuador, and Colombia, and south into the Paraguay-Paraná River systems in Paraguay, Argentina, and parts of Bolivia. They inhabit one of the world’s largest and most biodiverse freshwater ecosystems, occupying various river types from fast-flowing main channels to slow-moving tributaries, oxbow lakes, flooded forests, and seasonal pools.

The Amazon Basin, which contains the highest diversity and density of piranha species, undergoes dramatic seasonal changes that profoundly affect piranha behavior and distribution. During the wet season, rivers can rise by 9-15 meters, flooding vast areas of forest and creating an aquatic landscape called the várzea. Piranhas disperse into these flooded forests, where they find abundant food in the form of fruits, seeds, insects, and small fish. This seasonal abundance allows populations to grow and juveniles to mature in relative safety from larger predators.

When the dry season arrives and waters recede, piranhas become concentrated in smaller water bodies—permanent river channels, isolated pools, and shrinking lakes. These conditions dramatically increase competition for food and space, making piranhas more aggressive and increasing the likelihood of attacks on larger animals. In some regions, entire populations may become trapped in temporary pools that eventually dry completely, leading to mass mortality events that provide nutrients for the surrounding ecosystem.

Piranhas show preferences for specific microhabitats within their range. They typically favor areas with submerged vegetation, fallen trees, and other structures that provide cover for ambush hunting and protection from predators. Water conditions vary significantly across their range, from the clear, acidic blackwater rivers rich in tannins to the sediment-laden whitewater rivers originating in the Andes, to the greenwater rivers of intermediate chemistry. Piranhas have adapted to all these conditions, though specific species may show preferences for certain water types.

Temperature tolerance ranges from approximately 24 to 35 degrees Celsius, with optimal temperatures for most species between 26 and 30 degrees Celsius. Dissolved oxygen requirements vary by species, but most piranhas prefer well-oxygenated waters, though they can tolerate periods of lower oxygen during dry season conditions. The pH tolerance is similarly broad, ranging from acidic waters around 5.0 to more neutral conditions near 7.5.

Diet

Piranhas are primarily carnivorous opportunistic feeders, though their diet is far more varied and seasonal than their reputation suggests. The composition of their diet changes dramatically based on water level, season, and food availability. During the high-water season, many piranha species consume significant amounts of plant matter, including fruits, seeds, and aquatic vegetation. Studies of stomach contents have revealed that fruits and seeds can comprise up to 40% of the diet for some species during flood season, making them important seed dispersers in várzea ecosystems.

Fish constitute the primary animal protein source for most piranha species, including both living prey and carrion. They hunt smaller fish species, nipping fins and scales from larger fish, and scavenging dead or dying fish they encounter. The wimple piranha has evolved specialized behavior, feeding almost exclusively on scales and mucus scraped from other fish. Some species target the fins of other fish, a feeding strategy called lepidophagy, which allows the prey to survive and regenerate its fins, providing a renewable food source.

Piranhas also consume insects, crustaceans, mollusks, and other aquatic invertebrates, particularly juveniles that lack the jaw power to tackle larger prey. Larger piranha individuals and certain species will attack terrestrial animals that enter the water, including birds, mammals, and reptiles, though this behavior is most common during the dry season when other food sources are scarce. They are particularly attracted to blood and distress signals in the water, homing in on wounded animals with remarkable speed.

The feeding behavior that has spawned countless myths—the frenzied group attack on large animals—does occur but is relatively rare and primarily observed under specific conditions. When a large food source becomes available, piranhas employ a feeding strategy that appears chaotic but is actually individually motivated. Each fish attempts to bite and tear away flesh as quickly as possible, creating a violent spectacle of splashing water and snapping jaws. However, piranhas don’t actually cooperate during these events; they’re simply competing with each other to get as much food as possible before it’s gone.

Hunting strategies vary by species and situation. Some piranhas hunt actively, chasing down prey in open water using their speed and powerful tails. Others are ambush predators, hiding among vegetation or near structures and exploding toward unsuspecting prey. Their sensory systems are highly developed for hunting: excellent vision detects movement and identifies prey, lateral line organs sense vibrations and water displacement from potential meals, and their sense of smell detects blood and body fluids in the water even in low concentrations.

Predators and Threats

Despite being fierce predators themselves, piranhas occupy a middle position in their ecosystem’s food web and face predation from numerous larger animals. River dolphins, particularly the Amazon river dolphin or boto, are significant predators of adult piranhas. Caimans, the South American relatives of alligators, regularly prey on piranhas, as do giant otters, which hunt cooperatively in family groups and can overwhelm even adult piranhas. Large predatory fish, including the arapaima (one of the world’s largest freshwater fish), peacock bass, and various catfish species, consume piranhas of all ages.

Aquatic birds represent another threat, particularly to juvenile piranhas. Herons, cormorants, kingfishers, and the giant jabiru stork wade in shallow waters or dive from above to capture young piranhas. Terrestrial predators like jaguars occasionally catch piranhas when fishing in rivers and streams. Even within their own ranks, larger piranhas sometimes exhibit cannibalistic behavior, particularly toward juveniles and smaller individuals when other food sources are limited.

Human-caused threats to piranha populations have increased significantly in recent decades. Habitat destruction through deforestation, agricultural expansion, and dam construction represents the most severe long-term threat. Dams fragment river systems, preventing migration and gene flow between populations, while deforestation eliminates the flooded forest habitat crucial for feeding and reproduction. Mining operations, both legal and illegal, introduce toxic heavy metals like mercury into river systems, poisoning fish and disrupting ecosystem function.

Climate change poses emerging threats through altered rainfall patterns, extended droughts, and increased water temperatures. Severe droughts reduce available habitat, increase competition, and can lead to mass mortality events. The 2023 Amazon drought, one of the most severe on record, killed millions of fish including piranhas as rivers and lakes dried up completely in some areas. Changes in flooding patterns also affect the seasonal food sources piranhas depend on, particularly the fruits and seeds that become available during high water.

Pollution from agricultural runoff introduces pesticides and fertilizers into waterways, causing algal blooms that deplete oxygen and poison aquatic life. Urban development brings sewage, industrial chemicals, and trash into rivers where piranhas live. While piranhas show some tolerance for degraded conditions, chronic pollution reduces population health, reproductive success, and overall ecosystem quality.

The aquarium trade captures thousands of piranhas annually for export to pet markets worldwide. While this doesn’t threaten overall populations, localized collection pressure can impact specific areas, particularly when combined with other stressors. More concerning is the introduction of piranhas to ecosystems outside their native range through aquarium releases, which has occurred in parts of North America, Asia, and elsewhere, potentially threatening native species.

Reproduction and Life Cycle

Piranha reproduction is closely tied to seasonal water level changes, with most species spawning during the rising water or early flood season, typically between November and March in the southern Amazon Basin. This timing ensures that larvae and juveniles have access to the abundant food resources and protective habitat of flooded forests during their vulnerable early development.

Mating rituals vary among species but generally involve complex courtship behaviors. Males establish and defend breeding territories in shallow water areas with vegetation or sandy substrates. They display to females by swimming in circles, producing vocalizations, and exhibiting their brightest coloration. Males become highly aggressive toward other males during this period, engaging in ritualized combat that involves jaw locking, circling, and attempts to bite each other’s fins. These contests rarely result in serious injury but establish dominance and breeding access.

Once a female accepts a male’s advances, spawning occurs in a prepared nest area. Red-bellied piranhas, the most studied species, typically lay between 1,000 and 5,000 eggs, depending on the female’s size and condition. The male fertilizes eggs externally as the female deposits them on submerged vegetation, roots, or carefully cleaned sections of the substrate. The eggs are adhesive and sticky, attaching firmly to the spawning surface.

Parental care in piranhas is surprisingly extensive for a fish species. Males guard the eggs aggressively, attacking any intruders regardless of size, including animals many times larger than themselves. This protection continues for approximately 10 days until the eggs hatch, with the male constantly fanning the eggs with his fins to ensure adequate oxygenation and removing any that become infected with fungus. During this period, males rarely feed, devoting all their energy to nest defense.

Newly hatched larvae are tiny, approximately 4-5 millimeters long, with a large yolk sac that provides nutrition for the first few days of life. The larvae remain attached to vegetation through an adhesive organ on their heads, absorbing their yolk sac over 3-4 days before becoming free-swimming. At this point, parental care ends, and the juveniles must fend for themselves in the flooded forest habitat.

Juvenile piranhas initially feed on microscopic organisms—zooplankton, insect larvae, and other tiny invertebrates. As they grow, their diet shifts to larger prey items, and their characteristic teeth begin developing. Growth rates vary by species and food availability, but juveniles typically reach 5-8 centimeters in their first year. Sexual maturity is reached between 1 and 2 years of age, with males often maturing slightly earlier than females.

The lifespan of piranhas in the wild is estimated at 8-15 years, though precise aging is difficult and few long-term studies exist. Captive individuals with consistent food and protection from predators have lived up to 20 years, suggesting that predation and environmental stress are major mortality factors in natural populations. Growth continues throughout life, though it slows significantly after sexual maturity is reached.

Mortality is extremely high among eggs and larvae due to predation, disease, and environmental factors. Estimates suggest that fewer than 1% of eggs survive to adulthood. Juvenile survival remains low until fish reach sufficient size to defend themselves or effectively join protective schools, usually at 8-12 centimeters in length.

Population

Assessing piranha populations presents significant challenges due to the vast geographic range, habitat diversity, and logistical difficulties of conducting comprehensive surveys in remote Amazonian regions. Most piranha species are currently classified as Least Concern by the International Union for Conservation of Nature, indicating that they are not currently at immediate risk of extinction. This classification reflects their wide distribution, large overall population numbers, and adaptability to various aquatic habitats.

However, this categorization masks considerable variation among species and populations. Some localized populations have experienced declines due to habitat destruction, pollution, and overfishing. Certain species with more restricted ranges or specialized habitat requirements may face greater vulnerability than the common red-bellied piranha, though insufficient data exists to make definitive assessments for many species.

Estimating total population numbers for piranhas is essentially impossible given the scale of South American river systems and the difficulty of surveying aquatic populations in remote, often inaccessible areas. Scientific studies provide density estimates for specific locations and habitats, which vary enormously depending on season, water level, and local conditions. During dry season low water, densities can reach several hundred individuals per small pool, while during high water, piranhas disperse over vast areas at much lower densities.

Population trends appear stable for most widespread species, though long-term monitoring data is limited. The greatest concerns exist for populations in areas experiencing rapid development, particularly near major cities and in regions with intensive agriculture or mining. Some tributaries and smaller river systems have seen localized population declines or changes in species composition as environmental conditions deteriorate.

The Amazon Basin’s overall health directly determines piranha population viability. Recent research suggests that approximately 17% of the original Amazon rainforest has been lost to deforestation, with another 17% degraded to varying degrees. River systems throughout the basin face increasing pressure from dams, with more than 140 large dams currently in operation and hundreds more proposed or under construction. These changes fragment habitats and alter the seasonal flooding patterns that piranhas and countless other species depend on for survival.

Climate change effects are becoming increasingly apparent, with more frequent and severe droughts like those in 2010, 2015, and 2023 causing mass fish die-offs when rivers and lakes dry up completely. These events can devastate local piranha populations, though recovery typically occurs within a few years if habitat remains intact. However, if droughts become more frequent and severe as climate models predict, recovery periods may prove insufficient, potentially leading to longer-term population declines.

An interesting conservation consideration is the piranha’s ecological importance. They serve as both predators and prey in complex food webs, help control populations of smaller fish, clean water bodies by consuming carrion, and disperse seeds for many plant species during flood season. The loss or decline of piranha populations could have cascading effects throughout their ecosystems, affecting everything from water quality to forest regeneration.

Conclusion

The piranha’s journey from Hollywood villain to misunderstood marvel reveals much about how we perceive the natural world. These remarkable fish are neither the mindless killers of fiction nor helpless victims deserving of our pity—they are sophisticated predators perfectly adapted to one of Earth’s most dynamic ecosystems. With their self-sharpening teeth, acoustic communication, seasonal diet shifts, and surprising timidity, piranhas demonstrate nature’s genius for creating survivors.

The real threat to piranhas comes not from sensationalized stories but from the steady degradation of the rivers and forests they call home. As the Amazon faces unprecedented pressures from development, climate change, and resource extraction, piranhas serve as indicators of ecosystem health. Their continued abundance suggests thriving rivers, while their decline signals broader environmental collapse.

Understanding and appreciating piranhas for what they truly are—complex, ecologically important fish shaped by millions of years of evolution—represents a critical step toward protecting the Amazon Basin and its countless inhabitants. The next time you hear the word “piranha,” remember that behind the myth lies a reality far more fascinating than fiction, and one deserving of our respect and conservation efforts. The fate of these misunderstood predators is inextricably linked to the fate of the world’s greatest rainforest, making their survival a matter of global importance.

Scientific Name: Pygocentrus nattereri (red-bellied piranha) and related species

Diet Type: Carnivorous/Opportunistic omnivore

Size: 15-50 cm (6-20 inches), depending on species

Weight: 0.5-4 kg (1-9 pounds), depending on species

Region Found: South America (Amazon, Orinoco, and Paraguay-Paraná river basins)