In the kaleidoscopic world beneath Caribbean waves, few creatures command attention quite like the queen angelfish. Adorned with electric blue scales edged in brilliant yellow and crowned with a distinctive sapphire spot on its forehead, this regal reef dweller glides through coral gardens like aquatic royalty. But there’s far more to this stunning fish than its jewel-toned appearance. The queen angelfish plays a crucial role in maintaining the delicate balance of coral reef ecosystems, acting as both a selective grazer and an unwitting architect of reef health.

What makes this species truly fascinating is not just its beauty, but its remarkable adaptations: from juveniles that operate underwater “cleaning stations” to remove parasites from larger fish, to adults that can consume toxic sponges that would sicken most other creatures. The queen angelfish represents a perfect example of how evolution has sculpted a species to thrive in one of Earth’s most competitive and colorful habitats.

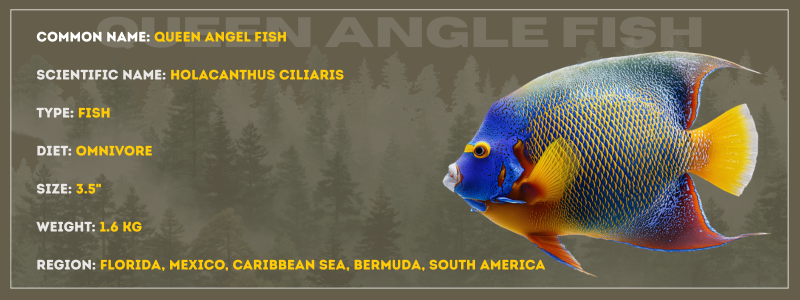

Facts

Here are seven intriguing facts about the queen angelfish that showcase its unique nature:

- Crown Jewel Identification: The species gets its royal name from a distinctive cobalt blue “crown” spot on its forehead, encircled by electric blue and dotted with bright blue speckles, which distinguishes it from its close relative, the Bermuda blue angelfish.

- Hybrid Royalty: Queen angelfish can interbreed with Bermuda blue angelfish to produce fertile hybrids called Townsend angelfish, which can themselves reproduce with either parent species or with other hybrids.

- Prolific Reproducers: A single female can release between 25,000 to 75,000 eggs each evening, producing up to ten million eggs during one spawning cycle.

- Toxic Diet: Adult queen angelfish primarily eat sponges, with studies showing that 90% of their diet consists of these organisms, many of which contain compounds toxic to other fish.

- Color Morphs: Seven distinct color variations have been recorded off Brazil’s Saint Peter and Saint Paul Archipelago, including bright orange, all white, and predominantly blue specimens.

- Juvenile Janitors: Young queen angelfish establish cleaning stations on the reef where larger fish come to have parasites and dead scales removed, creating temporary truces between predators and prey.

- Lightning-Fast Development: After eggs hatch in just 15 to 20 hours, the larvae develop functional eyes, fins, and digestive systems within 48 hours.

Species

The queen angelfish belongs to a taxonomic lineage that places it among the most ornate marine fish:

- Kingdom: Animalia

- Phylum: Chordata

- Class: Actinopterygii (ray-finned fishes)

- Order: Perciformes

- Family: Pomacanthidae (marine angelfishes)

- Genus: Holacanthus

- Species: Holacanthus ciliaris

Carl Linnaeus first described the species in 1758 as Chaetodon ciliaris, then moved to the genus Holacanthus in 1802 by French naturalist Bernard Germain de Lacépède. The genus name derives from Ancient Greek words meaning “full spine,” while the species name “ciliaris” means “fringed,” referring to the fish’s ciliate scales.

The genus Holacanthus includes several closely related species. The queen angelfish’s nearest relative is the Bermuda blue angelfish (Holacanthus bermudensis), which shares much of its range and appearance but lacks the distinctive crown marking. Other members of the genus include the Guinean angelfish (Holacanthus africanus) off West Africa and several species in the Eastern Pacific that diverged when the Isthmus of Panama closed approximately 3 million years ago.

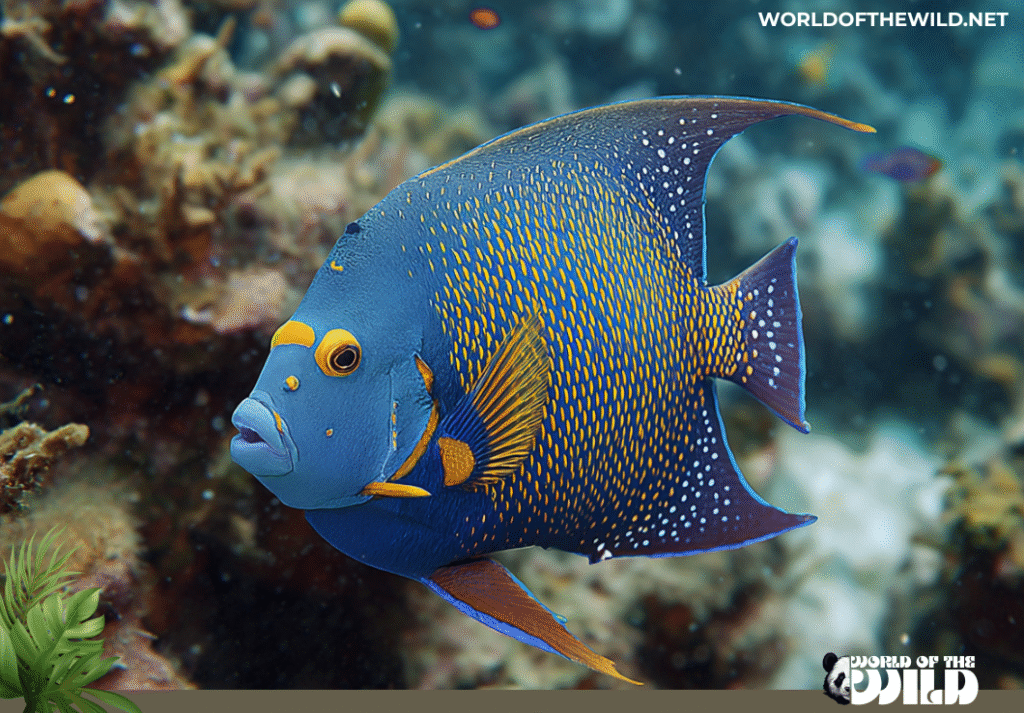

Appearance

The queen angelfish is a living masterpiece of marine evolution, designed to dazzle and deceive in equal measure. These fish can grow up to 18 inches in length and weigh up to three and a half pounds, making them fairly large for reef-dwelling fish.

Their body is dramatically flattened from side to side, creating an oval profile that allows them to navigate through narrow coral crevices. The body features electric blue coloring with blazing yellow tails and light purple and orange highlights. Individual scales on the body are rimmed in yellow, creating a delicate lattice pattern over the blue-green base. The face is predominantly yellow except for the blue lips and the characteristic crown.

The fish possesses elongated dorsal and anal fins that trail behind the body like flowing robes, while the tail fin is truncate and solid yellow. The dorsal fin contains 9 to 15 spines with 15 to 17 soft rays, and there’s a strong spine at the angle of the gill cover that helps protect the fish.

Perhaps most striking is how juvenile coloration differs from adults. Juveniles display dark blue bodies with curved, brilliant blue vertical stripes and yellow in the pectoral area and tail. As they mature, these patterns gradually transition through intermediate stages before achieving the full adult coloration.

Behavior

Queen angelfish exhibit complex social behaviors that reflect their adaptation to reef life. Their social structure consists of harems which include one male and up to four females, living within a territory where females forage separately and are tended to by the male. Despite this harem structure, mating pairs appear to form long-term bonds, as they’re typically observed in consistent pairs year-round.

These fish are generally shy and wary, though they occasionally show curiosity toward divers, observing them from a safe distance. They use their pectoral fins for precise swimming movements, allowing them to dart in and out of coral formations with remarkable agility when threatened.

Communication in queen angelfish is sophisticated and largely visual. They can temporarily change their coloration to communicate, particularly during mating and territorial displays. Their lateral line system—a series of fluid-filled ducts running along their body—detects pressure changes and vibrations in the water, alerting them to approaching predators or prey.

Juveniles exhibit distinctly different behaviors from adults. Rather than feeding on sponges, they establish and defend cleaning stations where they remove ectoparasites from larger fish. This cleaning behavior provides both food and protection, as predatory fish seeking parasite removal typically don’t attack their cleaners.

Evolution

Marine angelfish of the genus Holacanthus likely emerged between 10.2 and 7.6 million years ago during the late Miocene epoch. The evolutionary story of these fish is intimately connected with major geological events that shaped ocean basins and isolated populations.

The most basal species is the Guinean angelfish off West Africa, indicating that the lineage colonized the Atlantic from the Indian Ocean. This suggests an ancient migration pattern before the Atlantic and Indian Oceans were separated by landmasses.

The closure of the Isthmus of Panama approximately 3.5 to 3.1 million years ago led to the splitting of Tropical Eastern Pacific species, creating distinct populations on either side of Central America. This geological event is one of the most important in recent Earth history for marine speciation.

The queen angelfish split from its sister species, the Bermuda blue angelfish, around 1.5 million years ago. Despite this divergence, the two species remain compatible for breeding, producing fertile hybrid offspring. This suggests they are still in the relatively early stages of speciation, where reproductive isolation is incomplete.

The evolution of the queen angelfish’s ability to feed primarily on sponges represents a significant adaptive achievement. Sponges contain compounds that are toxic or deterrent to most fish, but queen angelfish have developed specialized digestive systems that can process these organisms safely, allowing them to exploit a food source with relatively little competition.

Habitat

Queen angelfish are creatures of warm, tropical waters with very specific habitat requirements. They are found in tropical and subtropical areas of the Western Atlantic Ocean around the coasts and islands of the Americas, occurring from Florida along the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean Sea down to Brazil. Their range extends eastward to Bermuda and the remote Saint Peter and Saint Paul Archipelago.

Queen angelfish are benthic or bottom-dwelling and occur from shallow waters close to shore down to 70 meters (230 feet). They show a strong preference for coral reef environments, particularly areas with soft corals, sea fans, and abundant sponge growth. They favor mature reef systems surrounding offshore islands rather than coastal reefs.

The species is most abundant throughout the Caribbean, where water temperatures remain warm year-round and coral reefs provide the complex three-dimensional structure these fish require. The reefs offer numerous hiding spots from predators, rich feeding grounds, and suitable surfaces for territorial establishment.

Queen angelfish don’t migrate, maintaining residence in specific reef areas throughout their lives. They establish and defend territories where they forage, with males maintaining larger territories that encompass the foraging areas of multiple females in harem-based social structures.

The health of coral reef habitats directly impacts queen angelfish populations. These fish depend on the abundance and diversity of sponges and other reef invertebrates that thrive in healthy coral ecosystems. As coral reefs face increasing stress from climate change and other factors, the habitats available to queen angelfish are increasingly threatened.

Diet

Queen angelfish are selective omnivores with a diet that evolves dramatically as they mature. Their feeding behavior plays an important role in maintaining the ecological balance of coral reefs.

Adult queen angelfish are specialized sponge-eaters. Studies off St. Thomas Island and Salvador, Bahia, found that 90% of adult diet consists of sponges. They possess small, beak-like mouths equipped with comb-like teeth perfectly adapted for grazing on sponge tissue. Their ability to digest sponges, which contain compounds that deter most other fish, gives them access to an abundant food source with minimal competition.

Beyond sponges, adult queen angelfish also consume tunicates, jellyfish, hydroids, bryozoans, soft corals, sea fans, algae, and plankton. Research at the Saint Peter and Saint Paul Archipelago documented more than 30 prey species, with 68% being sponges, 25% algae, and 5% bryozoans.

Juvenile queen angelfish have completely different dietary habits. Before settling on the reef, larvae feed exclusively on plankton floating in the water column. Once they establish themselves on the reef floor, juveniles feed on filamentous algae and operate as cleaner fish, removing ectoparasites and dead scales from larger fish that visit their cleaning stations.

This dietary specialization—both the shift from cleaning to sponge-eating and the ability to consume toxic sponges—represents a sophisticated evolutionary adaptation that allows queen angelfish to exploit different ecological niches throughout their life cycle.

Predators and Threats

Queen angelfish face threats from both natural predators and human activities, though predation in the wild remains poorly documented in scientific literature.

Natural predators include larger reef fish such as groupers, snappers, and barracudas that are capable of consuming adult queen angelfish. The fish’s laterally compressed body allows them to shimmy between corals to escape predators, while their vibrant coloration—though eye-catching to humans—actually helps them blend into the colorful reef environment. The crown marking may also serve as a false eye, making predators misjudge the fish’s size or orientation.

Human-caused threats pose more significant challenges to queen angelfish populations. The aquarium trade represents the primary human impact on this species. Queen angelfish are highly sought after for private and public aquariums due to their spectacular coloration. From 1995 to 2000, 43,730 queen angelfish were traded at Fortaleza in northeast Brazil, and in 1995, 75% of marine fish sold were queen and French angelfish combined. Brazil has implemented harvest management plans limiting collection to 10,000 specimens, though enforcement varies.

Climate change and coral reef degradation present growing threats. As ocean temperatures rise and coral bleaching events become more frequent, the reef habitats queen angelfish depend on are deteriorating. The loss of coral structure reduces available habitat and diminishes sponge populations, directly impacting the fish’s food supply.

Human consumption of this fish has been implicated in cases of ciguatera poisoning, caused by the bioaccumulation of ciguatoxins in the flesh. This naturally limits fishing pressure on the species, as they’re not targeted commercially for food.

Pollution, particularly coastal development and runoff, also degrades reef quality and can harm queen angelfish populations by reducing water quality and destroying essential habitat features.

Reproduction and Life Cycle

Queen angelfish exhibit fascinating reproductive behaviors that maximize their chances of successful offspring production in the challenging reef environment.

The species practices a harem-based mating system where dominant males court and mate with multiple females. Courtship involves elaborate displays where males perform what observers describe as “dancing,” extending their pectoral fins repeatedly to attract females. When a female responds positively, both fish swim upward through the water column together.

Breeding in the species occurs near a full moon, with spawning typically happening within minutes of sunset. The male and female ascend together, bringing their bellies close without actually touching. They release clouds of sperm and eggs simultaneously in the water column above the reef—a strategy called broadcast spawning that increases fertilization success while reducing predation on eggs.

Females can release anywhere from 25,000 to 75,000 eggs each evening and as many as ten million eggs during each spawning cycle. The eggs are transparent, buoyant, and pelagic, floating in the water column.

Eggs hatch after 15 to 20 hours into larvae that lack effective eyes, fins, or even a gut, with a large yolk sac that is absorbed after 48 hours. During this period, the larvae rapidly develop the physical characteristics needed for swimming. They remain in the planktonic stage for approximately three to four weeks, feeding on plankton and growing quickly.

At about 15-20mm in length, juvenile fish descend to the reef bottom and begin their benthic lifestyle. They settle among finger sponges and coral colonies that provide protection. As they mature, they transition through several color phases before achieving adult coloration at sexual maturity.

Average lifespan in the wild is up to 15 years, though individuals in well-maintained aquariums can reach similar ages with proper care. Queen angelfish reach sexual maturity within two to three years.

Once eggs are fertilized and released, there is no parental care—the young must survive independently from the moment of hatching, facing high mortality from predation and environmental challenges during their vulnerable larval stage.

Population

The queen angelfish currently enjoys a relatively secure conservation status, though localized pressures exist in some areas.

In 2010, the queen angelfish was assessed as Least Concern by the International Union for Conservation of Nature, as the wild population appeared to be stable. This assessment reflects the species’ wide distribution throughout the Caribbean and Western Atlantic, abundant populations in many areas, and the fact that most threats haven’t significantly impacted overall numbers.

While precise global population estimates aren’t available, queen angelfish remain relatively common throughout most of their range, particularly in the Caribbean. They’re frequently observed by divers and researchers in protected reef areas. However, population trends vary by location.

Some areas have experienced localized depletion, particularly where collection for the aquarium trade has been intense or sustained. The Saint Peter and Saint Paul Archipelago population faces particular vulnerability due to its unique color morphs, which command premium prices in the aquarium trade, though the remote location provides some protection.

Scientists believe that capture for aquariums and displays has not significantly affected queen angelfish populations in most places, but they have been depleted in some areas. Ongoing monitoring is essential to ensure collection remains sustainable.

The species faces no immediate extinction risk, though the broader threats facing coral reefs globally—including climate change, ocean acidification, and habitat destruction—could impact future populations. As obligate reef specialists highly dependent on healthy coral ecosystems, queen angelfish populations will likely track the health of Caribbean and Western Atlantic reef systems.

Marine protected areas throughout the Caribbean provide refuges where queen angelfish populations can thrive without fishing pressure or collection, serving as source populations that can replenish adjacent areas.

Conclusion

The queen angelfish stands as one of the Caribbean’s most iconic marine species, a living jewel that exemplifies both the beauty and complexity of coral reef ecosystems. From the distinctive crown that gives this fish its royal name to its remarkable ability to thrive on a diet that would poison most other creatures, every aspect of the queen angelfish reflects millions of years of evolutionary refinement.

These fish are far more than ornamental reef residents. As specialized sponge-eaters, they help regulate sponge populations and prevent these organisms from overwhelming corals in the competition for reef space. Juveniles provide cleaning services that benefit dozens of other reef species. In countless subtle ways, queen angelfish contribute to the intricate ecological web that keeps coral reefs healthy and diverse.

While current populations remain stable, the future of queen angelfish is inextricably linked to the fate of coral reefs. As climate change intensifies and reef ecosystems face mounting pressures, we must recognize that protecting these habitats protects not just the charismatic queen angelfish, but entire communities of marine life. Supporting marine protected areas, choosing sustainable seafood, using reef-safe products, and addressing climate change aren’t just conservation abstractions—they’re concrete actions that will determine whether future generations can witness these regal fish gliding through Caribbean waters. The queen angelfish has ruled the reef for over a million years; whether it continues to wear its crown depends largely on the choices we make today.

Quick Reference Guide: Queen Angelfish

Scientific Name: Holacanthus ciliaris

Diet Type: Omnivore (primarily spongivore – specialized sponge-eater)

Size: Up to 18 inches (45 cm) in length

Weight: Up to 3.5 pounds (1.6 kg)

Region: Western Atlantic Ocean, including:

- Florida and the Gulf of Mexico

- Caribbean Sea

- Bermuda

- Eastern coast of Central and South America down to Brazil

- Saint Peter and Saint Paul Archipelago

Habitat Depth: Shallow waters to 70 meters (230 feet) deep in coral reef environments