In the heart of summer, a flash of brilliant yellow darts across a meadow, its undulating flight pattern resembling a feathered roller coaster ride. This is the American Goldfinch, a bird so vibrantly colored it seems almost tropical, yet it thrives in backyards and wild spaces across North America. Unlike most birds that don their finest plumage for spring courtship, the male American Goldfinch saves his most dazzling transformation for the height of summer, earning him the affectionate nickname “wild canary.” This charismatic songbird captivates birdwatchers and casual observers alike, not just for its stunning appearance, but for its fascinating lifestyle that defies many avian conventions. From its vegetarian diet to its late breeding season, the American Goldfinch represents a remarkable example of evolutionary adaptation and ecological specialization.

Facts

- Late Bloomers: American Goldfinches are among the latest breeders of all North American birds, often not nesting until July or August when thistle seeds become abundant—some pairs don’t even start until September.

- Strict Vegetarians: They are one of the strictest vegetarians in the bird world, feeding almost exclusively on seeds even during breeding season when most birds switch to protein-rich insects for their young.

- Feather Fashion: Male goldfinches undergo two complete molts per year (most birds molt once), dramatically changing from brilliant yellow breeding plumage to drab olive-brown winter colors.

- Water-Resistant Nests: Female goldfinches weave their nests so tightly that they can hold water like a cup, occasionally drowning nestlings during heavy rainstorms.

- Nomadic Tendencies: Unlike many songbirds that return to the same territory each year, American Goldfinches are nomadic, wandering widely in search of abundant seed sources and rarely breeding in the same location twice.

- Acrobatic Feeders: Their feet are so strong and adapted for seed feeding that they can hang upside down from seedheads while extracting seeds, a behavior unusual among finches.

- Musical Range: Males can sing more than a dozen different song types, with songs lasting several seconds and containing complex phrases that vary by region, creating distinct “dialects.”

Species

The American Goldfinch belongs to the following taxonomic classification:

- Kingdom: Animalia

- Phylum: Chordata

- Class: Aves

- Order: Passeriformes

- Family: Fringillidae

- Genus: Spinus

- Species: Spinus tristis

The American Goldfinch has four recognized subspecies that vary primarily in size, bill dimensions, and the intensity of yellow coloration:

- Spinus tristis tristis: The nominate subspecies, found throughout most of the eastern and central range from southern Canada to the Gulf Coast.

- Spinus tristis pallidus: The pale goldfinch, inhabiting the Great Plains and western interior regions, slightly paler with a larger bill adapted for larger seeds.

- Spinus tristis jewetti: Found along the Pacific Coast from British Columbia to California, this subspecies is darker and more intensely colored with a smaller bill.

- Spinus tristis salicamans: The willow goldfinch, restricted to the southwestern United States, particularly California’s Central Valley, with intermediate characteristics.

The American Goldfinch is closely related to Lawrence’s Goldfinch (Spinus lawrencei) and the Lesser Goldfinch (Spinus psaltria), both found in western North America. These three species occasionally hybridize where their ranges overlap, though the American Goldfinch remains the most widespread and abundant.

Appearance

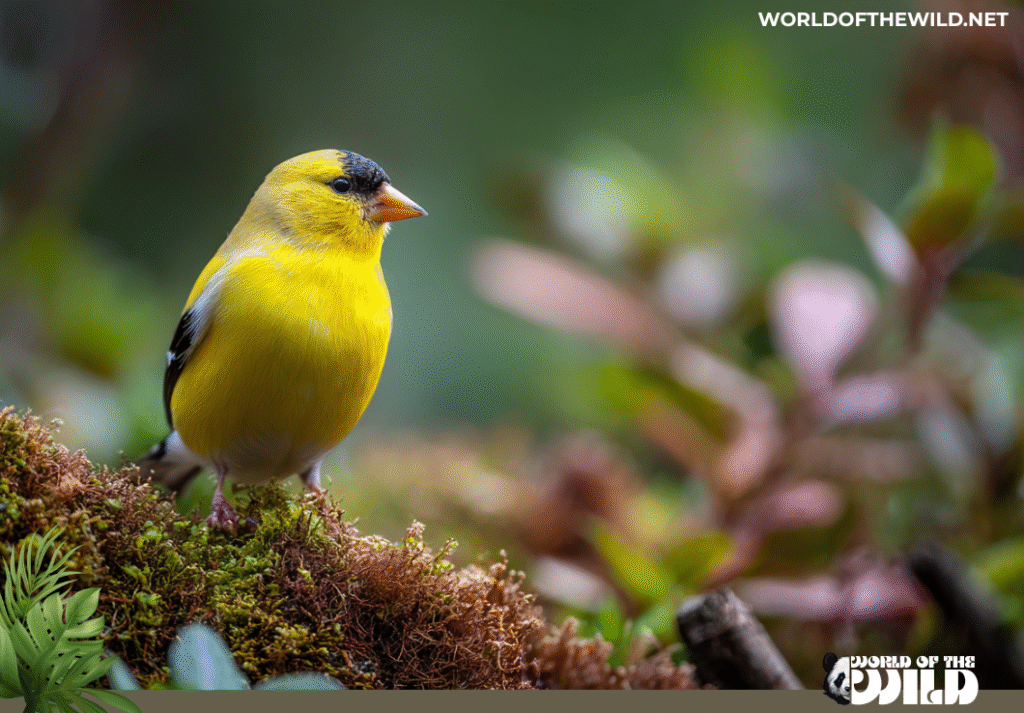

The American Goldfinch is a small, compact songbird measuring 11 to 14 centimeters (4.3 to 5.5 inches) in length with a wingspan of 19 to 22 centimeters (7.5 to 8.7 inches). Adults typically weigh between 11 and 20 grams (0.39 to 0.71 ounces), roughly equivalent to five U.S. quarters.

The species exhibits dramatic seasonal plumage changes, particularly in males. During the breeding season (late spring through early fall), adult males display brilliant lemon-yellow bodies with a striking black forehead patch, or “cap,” that extends from the bill to the crown. Their wings are black with bold white wingbars that create a striking contrast in flight. The tail is also black with white edges, and the bill transforms from its winter brown to a vibrant orange color.

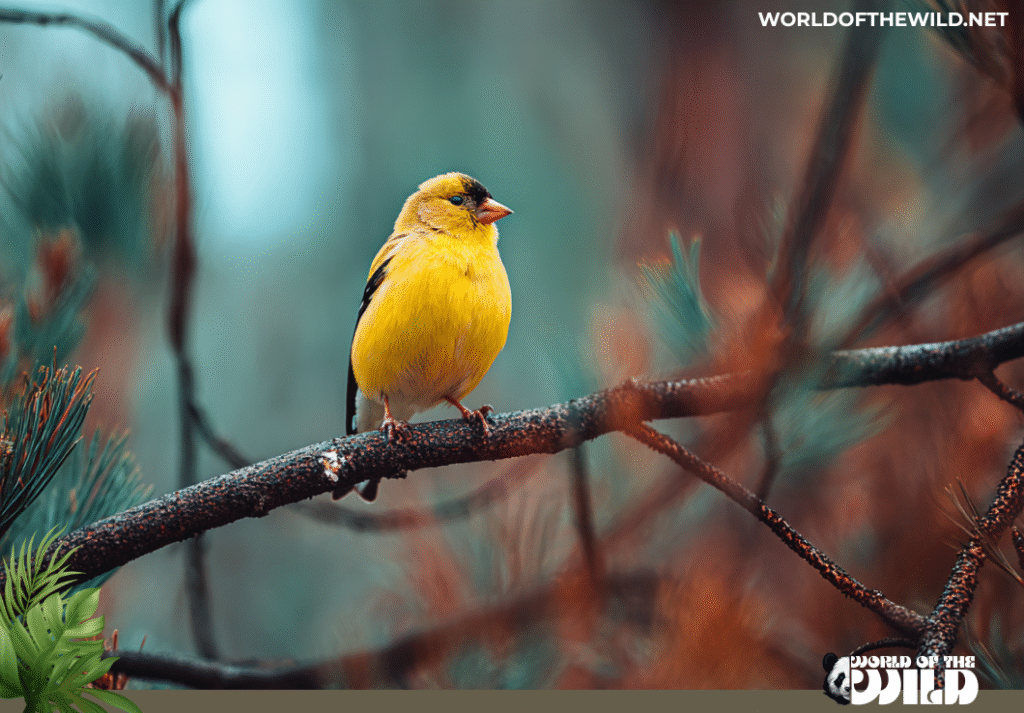

In winter, both sexes adopt more subdued plumage. Males lose their bright yellow coloration, becoming olive-brown above and pale yellow below, though they retain their distinctive black wings with white wingbars. The black cap disappears entirely during this season.

Females are less dramatically colored year-round, displaying olive-yellow to olive-brown plumage on their upperparts and paler yellow underparts. They lack the black cap even during breeding season but share the characteristic black wings with white wingbars. Juvenile birds resemble winter females but have brownish wingbars instead of white until their first molt.

The American Goldfinch has a short, conical bill perfectly adapted for extracting seeds from tightly packed seedheads. Their feet are relatively small but surprisingly strong, allowing them to perch on thin stems and even hang upside down while feeding—an ability rare among birds of their size.

Behavior

The American Goldfinch exhibits highly social behavior throughout most of the year, traveling in loose flocks that can number from a dozen to several hundred individuals, especially during winter and migration. These flocks often mix with other finch species, Pine Siskins, and Common Redpolls, creating diverse feeding aggregations. Their flight is distinctively undulating, with a characteristic “po-ta-to-chip” call given with each bound, creating a wavelike pattern as they alternately flap and glide.

Communication among goldfinches is complex and varied. Males are accomplished singers with a long, twittering song that includes canary-like trills, ascending notes, and musical warbles lasting several seconds. These songs are primarily used to establish territories and attract mates during the breeding season. Beyond song, goldfinches employ numerous calls for different situations: contact calls keep flock members together, aggressive calls ward off competitors at feeders, and alarm calls alert others to predators.

During the breeding season, which uniquely occurs in mid-to-late summer, males become territorial and perform elaborate courtship displays. The male flies in exaggerated, looping circles above a female while singing vigorously, then perches nearby and performs a “butterfly flight”—flying with slow, deliberate wingbeats while singing. If the female is receptive, she solicits feeding, and the male responds by regurgitating seeds to her, a bonding behavior that continues throughout nesting.

American Goldfinches demonstrate remarkable intelligence in problem-solving, particularly when accessing food. They learn to use bird feeders of various designs and can remember productive feeding sites over long periods. Their foraging technique is sophisticated: they carefully select seeds at peak ripeness, using their bill to hull seeds with remarkable efficiency, discarding the shell while consuming only the nutritious kernel.

One of their most distinctive behavioral adaptations is their strict adherence to a vegetarian diet. Unlike most songbirds that switch to insects during breeding season, goldfinches feed thistle and other seeds to their nestlings—a behavior made possible by timing their breeding to coincide with peak seed production. This dietary specialization has led to numerous behavioral adaptations, including their late breeding season and nomadic lifestyle.

During winter, goldfinches become even more gregarious, forming large flocks that roam widely in search of food sources. They exhibit a pecking order at feeders but are generally less aggressive than many other birds. Their social nature extends to roosting, where they gather in dense vegetation, sometimes huddling together on particularly cold nights for warmth.

Evolution

The American Goldfinch belongs to the family Fringillidae, the true finches, which originated approximately 20 million years ago during the early Miocene epoch. The family likely evolved in the mountain forests of Central Asia before diversifying and spreading across the Northern Hemisphere. Finches are characterized by their specialized seed-eating adaptations, including powerful jaw muscles and conical bills designed to crack tough seed coats.

The genus Spinus, which includes the goldfinches and siskins, represents a more recent evolutionary radiation within the finch family. Molecular studies suggest this genus diverged from other finches roughly 10 to 15 million years ago during the Miocene, a period of significant global cooling and grassland expansion that created new ecological niches for seed-eating specialists.

The American Goldfinch itself is thought to have evolved in North America within the last few million years, during the Pliocene and Pleistocene epochs. During this time, the continent experienced dramatic climate fluctuations and the expansion of open habitats—grasslands, meadows, and weedy areas—that provided abundant seed resources. These environmental changes drove the evolution of the goldfinch’s specialized adaptations, including its strict vegetarian diet, nomadic lifestyle, and late breeding season timed to thistle seed production.

The close relationship between American Goldfinches and plants in the Asteraceae family (particularly thistles) suggests a long coevolutionary history. As these plants proliferated in disturbed and open habitats, goldfinches evolved increasingly specialized anatomical and behavioral traits to exploit this reliable food source. Their tightly woven nests, constructed with thistle down, and their late breeding season both reflect this deep evolutionary relationship.

Fossil evidence for specific goldfinch evolution is limited, as small passerine bones rarely fossilize well. However, genetic studies comparing the American Goldfinch with its closest relatives—Lawrence’s Goldfinch and Lesser Goldfinch—indicate these species diverged relatively recently, likely within the last one to two million years as populations became geographically isolated and adapted to different regional conditions.

The evolutionary success of the American Goldfinch can be attributed to its flexibility in exploiting disturbed habitats created both naturally and by human activity. Their ability to thrive in agricultural areas, suburban gardens, and roadsides—environments that have expanded dramatically in recent centuries—demonstrates how their evolutionary history has pre-adapted them to benefit from human landscape modification.

Habitat

The American Goldfinch occupies an extensive range across North America, from southern Canada to northern Mexico. During the breeding season, they are found from coast to coast in southern Canada and throughout the United States, except for the extreme southern states along the Gulf Coast and into Texas. Their breeding range extends from Newfoundland in the east to British Columbia in the west, and south through the northern two-thirds of the United States.

In winter, northern populations migrate southward, with the species’ range contracting primarily to the United States and northern Mexico. Winter populations are densest across the southern and central United States, though some individuals remain year-round in milder regions, particularly along the Pacific Coast and in the Mid-Atlantic states.

American Goldfinches are habitat generalists that thrive in open and semi-open environments with scattered trees and shrubs. Their preferred habitats include weedy fields, overgrown pastures, meadows, floodplains, agricultural edges, orchards, and suburban gardens. They are particularly abundant in areas with plenty of composite flowers (Asteraceae family), especially thistles, sunflowers, and asters, which provide both food and nesting materials.

During the breeding season, goldfinches require three key habitat features: nearby water sources, scattered trees or large shrubs for nesting (particularly willows, maples, and other deciduous trees), and abundant seed-producing plants. They show strong preference for areas with multiple thistle species, as thistle seeds constitute their primary food during breeding, and thistle down provides essential nesting material. Riparian areas—habitats along streams and rivers—are particularly attractive because they offer dense shrubs for nesting and abundant moisture-loving plants that produce seeds.

These birds readily adapt to human-modified landscapes and have actually benefited from certain types of land use change. They thrive along roadsides where mowing prevents woody succession but allows annual and perennial forbs to flourish. Suburban areas with bird feeders, native plantings, and unmowed sections have become important habitats, and many homeowners specifically plant seed-producing flowers to attract goldfinches.

At higher elevations, American Goldfinches can be found in mountain meadows, aspen groves, and the edges of coniferous forests, though they generally avoid dense, unbroken forest. In winter, their habitat use becomes even more flexible, and they congregate wherever food is abundant—including weedy fields, agricultural areas with leftover crop seeds, and residential areas with bird feeders stocked with niger (thistle) seed or sunflower hearts.

The key to understanding goldfinch habitat preference is recognizing their dependence on herbaceous seed-producing plants. Unlike many songbirds that require specific forest types or structural features, goldfinches are following the seeds, making them nomadic and opportunistic in their habitat use.

Diet

The American Goldfinch is remarkable among North American birds for its almost exclusively vegetarian diet, maintained throughout the entire year including the breeding season. This dietary specialization distinguishes them from the vast majority of songbirds, which rely heavily on insects, especially when feeding nestlings.

Seeds form approximately 95% of the American Goldfinch’s diet, with the remaining 5% consisting of occasional insects (often consumed accidentally with seeds) and small amounts of berries and plant buds. Their strongly conical bill and powerful jaw muscles are perfectly adapted for cracking open tough seed coats and extracting the nutritious kernels inside.

Among seeds, goldfinches show strong preferences for plants in the Asteraceae (composite) family. Thistle seeds are particularly favored and nutritionally important; in fact, the bird’s scientific name tristis (meaning “sad”) may reference the association with thistle, historically viewed as a “sad” or undesirable weed. Beyond thistles, they consume seeds from dandelions, sunflowers, asters, ragweed, and coneflowers. Other important food plants include seeds from birch trees, alder, elm, and various grasses and weeds like lamb’s quarters, pigweed, and knotweed.

The goldfinch’s feeding technique is sophisticated and efficient. When foraging on composite flowers, they perch on the seedhead—or hang acrobatically upside-down—and use their bill to systematically extract seeds. They manipulate each seed with their tongue, crack the hull with precise pressure from their bill, and discard the shell while swallowing only the kernel. This process, called “hulling,” allows them to maximize nutritional intake while minimizing the consumption of indigestible material.

Their foraging behavior changes seasonally based on seed availability. In spring and early summer, before most herbaceous plants have gone to seed, goldfinches feed heavily on tree seeds, particularly from birch, alder, and elm. By mid-summer, as thistles and other composites mature, these become the primary food source. In fall and winter, they exploit seeds from a wider variety of plants, including dried flower heads, weed seeds in agricultural fields, and seeds held in trees.

At bird feeders, American Goldfinches show strong preferences for niger seed (Guizotia abyssinica), often called “thistle seed” though it’s actually from a plant native to Ethiopia. They also readily consume hulled sunflower hearts (sunflower chips) and occasionally nyjer and other small seeds. Their feeder behavior demonstrates learned preferences, and they quickly adapt to new feeder designs.

The vegetarian lifestyle of goldfinches creates interesting nutritional challenges, particularly during breeding. Most birds feed protein-rich insects to their growing nestlings because insect protein contains essential amino acids needed for rapid growth. Goldfinches overcome this limitation in two ways: first, by timing their breeding to coincide with peak seed production when seeds are at their most nutritious, and second, by selecting seeds with relatively high protein content. Thistle seeds, for instance, contain about 20% protein—higher than many other seeds.

This strict seed diet also explains the goldfinch’s late breeding season. By waiting until July and August, when thistle and other preferred seeds are abundant and nutritionally optimal, goldfinches ensure their nestlings receive adequate nutrition despite the all-seed diet. This remarkable adaptation demonstrates how diet can shape fundamental aspects of a species’ life history.

Predators and Threats

Despite their bright coloration during breeding season, American Goldfinches face predation throughout their life cycle, from eggs to adults. The most significant natural predators vary by life stage and season.

Nest predators pose the greatest threat to goldfinch reproductive success. Common nest raiders include Blue Jays, which systematically search shrubs for nests and consume both eggs and nestlings; American Crows, which are opportunistic and intelligent nest predators; and various snake species, particularly rat snakes and garter snakes, which can climb into shrubs and trees to access nests. Small mammals including raccoons, squirrels, and domestic cats also prey on goldfinch nests when they can reach them.

Adult goldfinches face predation primarily from aerial hunters. Sharp-shinned Hawks and Cooper’s Hawks are perhaps their most significant avian predators, specializing in catching small songbirds in flight or at feeders. American Kestrels occasionally take goldfinches, particularly during migration when finches are crossing open areas. Merlins also prey on goldfinches during migration periods. On the ground, domestic and feral cats represent a substantial threat, particularly in suburban and rural areas where goldfinches visit feeders and forage on low vegetation.

Beyond natural predation, American Goldfinches face several anthropogenic threats, though none currently threaten the species’ overall population. Habitat loss and degradation represent ongoing concerns, particularly the elimination of weedy fields and meadows through intensive agriculture and suburban development. The widespread use of herbicides eliminates the native and non-native “weed” species that goldfinches depend upon for food, while the trend toward manicured lawns and tidy gardens reduces available habitat.

Pesticide use poses both direct and indirect threats. While goldfinches’ vegetarian diet insulates them somewhat from direct pesticide poisoning (compared to insect-eating birds), they can still be exposed through treated seeds. More significantly, pesticides reduce the abundance and diversity of seed-producing plants in agricultural and suburban landscapes.

Window collisions kill thousands of goldfinches annually, particularly at residential buildings with bird feeders nearby. The combination of reflective glass and the birds’ frequent movement between feeders and nearby cover makes them vulnerable to these strikes.

Climate change presents emerging concerns for goldfinch populations. Shifts in temperature and precipitation patterns could alter the timing of plant seed production, potentially disrupting the synchrony between goldfinch breeding and peak seed availability. Changes in plant community composition could also affect food availability across their range.

During winter, severe weather events can cause mortality, particularly ice storms that encase seed sources in ice, making them inaccessible. Prolonged periods of deep snow can similarly make ground-level seeds unavailable, though goldfinches are generally more resilient to winter weather than many other small songbirds due to their ability to exploit seeds from standing dead plants and trees.

Despite these various threats, American Goldfinch populations remain stable and robust. Their adaptability to human-modified landscapes, their popularity among bird feeding enthusiasts (who provide supplemental food), and their wide geographic range all contribute to the species’ continued success. Unlike many grassland birds that have experienced severe declines, goldfinches have actually benefited from certain types of habitat disturbance that create the early successional habitats they prefer.

Reproduction and Life Cycle

The American Goldfinch follows an unusual breeding timeline that sets them apart from virtually all other North American songbirds. While most temperate-zone birds breed in spring or early summer, goldfinches delay breeding until mid-to-late summer, with most pairs not initiating nests until July or August—some even as late as September. This remarkable adaptation synchronizes their breeding with the peak abundance of thistle and other composite seeds, ensuring optimal nutrition for their vegetarian offspring.

The breeding season begins with males molting into their brilliant yellow plumage and establishing territories through song. Male goldfinches perform elaborate courtship displays, flying in wide circles 20 to 30 feet above a prospective mate while singing continuously. This “circle flight” is accompanied by the distinctive “perchickery” song. Males also perform shorter flights between perches, flying with exaggerated, moth-like wingbeats while singing. Once paired, the male feeds the female in a bonding ritual that continues throughout incubation.

Nest building is exclusively the female’s responsibility, though the male accompanies her and may indicate potential nest sites. The female selects a location typically 4 to 30 feet above ground in the fork of a deciduous shrub or tree, with willows, maples, and other broadleaf species preferred. She constructs a remarkably compact cup nest over 6 to 10 days, using grass, bark strips, and plant fibers for structure, and lining it with plant down—especially thistle down—which creates a soft, insulated interior. The nest is woven so tightly that it can hold water, which occasionally becomes problematic during heavy rains.

The female lays 4 to 6 pale blue eggs (occasionally 2 to 7) over consecutive days, typically producing one egg each morning. Once the clutch is complete, she begins incubation, which lasts 12 to 14 days. During this period, the male brings food to the female on the nest, feeding her through regurgitation. Unlike many bird species where males share incubation duties, male goldfinches never incubate; the female alone maintains the eggs’ temperature.

Nestlings hatch altricial—blind, naked, and completely helpless. Both parents feed the chicks by regurgitating a paste of partially digested seeds mixed with saliva. The vegetarian diet means goldfinch chicks develop more slowly than insect-fed young of other species; they remain in the nest for 11 to 17 days, longer than many similarly sized songbirds. Even after fledging, the young remain dependent on their parents for another 3 weeks while they learn to forage efficiently.

American Goldfinches frequently raise two broods per season, with the female sometimes beginning construction of a second nest while the male continues feeding the first brood’s fledglings. Some pairs even attempt three broods in particularly favorable conditions, though this is less common. Remarkably, pairs often choose new mates for second broods, making goldfinches relatively unusual among songbirds in their flexible pair bonds.

Juvenile goldfinches molt into their first winter plumage by early fall and are virtually indistinguishable from adult females during their first winter. They reach sexual maturity at one year of age and typically breed in their first summer.

In the wild, American Goldfinches have an average lifespan of 3 to 6 years, though the maximum recorded lifespan is 10 years and 11 months for a wild individual (based on bird banding data). Annual survival rates for adults are estimated at 40-60%, typical for small songbirds. The greatest mortality occurs during the first year of life, with nest predation and the vulnerability of recently fledged birds representing the most critical periods.

One fascinating aspect of goldfinch reproduction is their apparent ability to assess environmental conditions and adjust breeding effort accordingly. In years with poor seed production, they may skip breeding entirely or produce smaller clutches, demonstrating a flexible reproductive strategy that helps ensure their survival through variable environmental conditions.

Population

The American Goldfinch is currently classified as Least Concern by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), reflecting its large population, extensive range, and stable or increasing population trends across most of its distribution. This favorable conservation status makes the American Goldfinch one of North America’s most secure songbird species.

Global population estimates for the American Goldfinch range from 42 to 72 million individuals, with Partners in Flight, a consortium of conservation organizations, estimating approximately 57 million mature individuals. This abundance ranks the species among the more numerous landbirds in North America. The species is also rated relatively low in terms of conservation concern, scoring 8 out of 20 on Partners in Flight’s Continental Concern Score, where higher scores indicate greater conservation need.

Long-term population trends for American Goldfinches are complex and vary by region. According to data from the North American Breeding Bird Survey (BBS), which has monitored bird populations since 1966, the continental population has remained relatively stable overall, with perhaps a slight decline of less than 1% per year cumulatively over the past 50+ years. However, regional trends show more variation: populations have increased in some areas of the western United States and southern Canada while declining modestly in parts of the northeastern and midwestern United States.

Several factors contribute to the American Goldfinch’s population stability. Their adaptability to human-modified landscapes has allowed them to thrive in suburban and agricultural areas that would be unsuitable for many other grassland and edge-dependent species. The popularity of bird feeding, particularly the widespread offering of niger seed, provides supplemental food that may enhance winter survival, especially during harsh weather. Additionally, their wide dietary flexibility allows them to exploit various seed sources, buffering them against localized food shortages.

The species has benefited from certain landscape changes, particularly the creation of early successional habitats along roadsides, utility corridors, and in suburban areas where maintained but unmowed spaces allow weedy seed-producing plants to flourish. Paradoxically, while intensive agriculture has harmed many grassland bird species, the weedy edges of agricultural fields and the seeds from certain crop plants have provided new food sources for goldfinches.

However, the species is not without population challenges. In some regions, particularly portions of the Northeast, declines have been attributed to habitat loss from suburban sprawl, increased use of herbicides that eliminate food plants, and changes in agricultural practices that reduce field borders and hedgerows. The trend toward tidy, manicured landscapes in residential areas reduces the “weedy” plants goldfinches depend upon.

Christmas Bird Count data, which tracks winter bird populations, shows that American Goldfinch numbers fluctuate considerably from year to year in response to food availability and weather, but without strong directional trends. This suggests that the species’ population dynamics are driven more by annual environmental variation than by systematic declines.

Looking forward, conservation priorities for American Goldfinches focus on maintaining habitat quality rather than preventing extinction. Key recommendations include preserving weedy fields and meadow habitats, maintaining hedgerows and field borders in agricultural landscapes, reducing herbicide use in non-crop areas, and encouraging native wildflower plantings in residential and public spaces. Many conservation organizations promote leaving seed heads standing through winter rather than cutting them down in fall, providing both food for goldfinches and other seed-eating birds.

The species’ abundance and widespread distribution across North America mean that many people regularly encounter American Goldfinches, making them excellent ambassadors for conservation. Their presence at bird feeders creates opportunities for public engagement with nature, and their popularity among birdwatchers ensures ongoing monitoring and interest in their population status.

Conclusion

The American Goldfinch stands as a testament to the power of evolutionary specialization and ecological adaptation. This brilliant yellow bird has carved out a unique niche in North American ecosystems by becoming a strict vegetarian that breeds in late summer, defying the conventional wisdom that governs most temperate songbirds. From its remarkable seasonal plumage transformations to its intricate relationship with thistle and other seed-producing plants, the goldfinch exemplifies how species can thrive through specialized adaptations.

Despite facing predation, habitat loss, and environmental changes, American Goldfinch populations remain robust, a success story in an era when many bird species face decline. Their ability to adapt to human-modified landscapes—suburban gardens, agricultural edges, and even urban parks—demonstrates a flexibility that has served them well in our changing world. Yet their success depends on maintaining the diverse, seed-rich habitats they require.

As we continue to shape the landscapes around us, the American Goldfinch reminds us of an essential truth: conservation doesn’t always require vast wilderness areas. Sometimes it’s as simple as letting a patch of native wildflowers grow, leaving seed heads standing through winter, or planting coneflowers and sunflowers in our gardens. Every unmowed field edge, every thistle allowed to bloom, and every bird feeder stocked with niger seed contributes to the survival of these captivating birds. In protecting the habitat and resources that goldfinches need, we create spaces that benefit countless other species—from native bees that pollinate those same flowers to other seed-eating birds that share the goldfinch’s dietary preferences. The next time you see that flash of yellow bounding through the summer sky, remember: you’re witnessing millions of years of evolution in action, and you have the power to ensure this natural wonder continues brightening our world for generations to come.