Standing atop a fractured ice floe, a massive white bear surveys the frozen seascape with obsidian eyes, its breath crystallizing in the Arctic air. The polar bear is not merely surviving in one of Earth’s most hostile environments—it is thriving as the apex predator of the frozen north. This magnificent creature represents one of nature’s most remarkable adaptations to extreme cold, embodying both raw power and surprising vulnerability. As the ice beneath its paws grows thinner with each passing year, the polar bear has become an unwitting symbol of our changing planet, making it one of the most significant animals of our time.

Facts

- Polar bears are the largest land carnivores on Earth, though they spend most of their lives on sea ice rather than true land.

- Their skin is actually black underneath that iconic white fur, which helps absorb and retain heat from the sun.

- Polar bear fur isn’t truly white—each hair is a hollow, transparent tube that reflects light, creating the white appearance while providing exceptional insulation.

- They can swim continuously for days, with one recorded individual swimming 426 miles over nine days without rest.

- A polar bear’s sense of smell is so acute it can detect a seal nearly a mile away and buried beneath three feet of snow.

- Despite their massive size, polar bears can reach sprinting speeds of 25 miles per hour on ice.

- They have been observed using tools, including throwing blocks of ice at walruses to hunt them—a rare behavior among mammals.

Sounds of the Polar Bear

Species

The polar bear belongs to the following taxonomic classification:

Kingdom: Animalia

Phylum: Chordata

Class: Mammalia

Order: Carnivora

Family: Ursidae

Genus: Ursus

Species: Ursus maritimus

Unlike many other bear species, the polar bear has no recognized subspecies. However, genetic studies have identified distinct subpopulations based on geographic location and genetic variation. Currently, scientists recognize 19 relatively discrete subpopulations scattered across the circumpolar Arctic, ranging from the Chukchi Sea to the Barents Sea. These subpopulations show some genetic differentiation but remain part of the same species.

The polar bear’s closest living relative is the brown bear (Ursus arctos), and the two species can produce fertile hybrid offspring known as “grolar bears” or “pizzly bears,” though this primarily occurs in captivity or in rare instances where their ranges overlap due to climate-induced habitat changes.

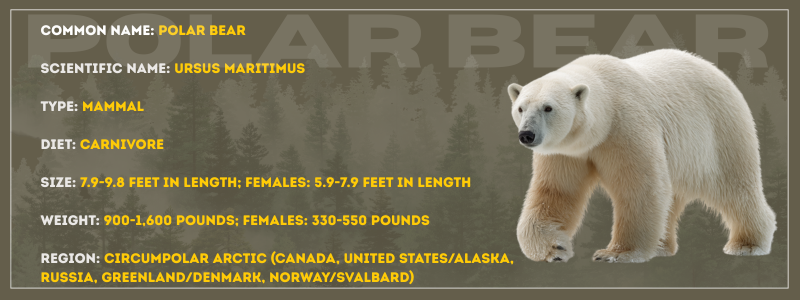

Appearance

The polar bear is an imposing creature built for Arctic survival. Adult males typically measure 7.9 to 9.8 feet in length and stand about 4.3 to 5.3 feet tall at the shoulder when on all fours. Females are considerably smaller, measuring 5.9 to 7.9 feet in length. The sexual dimorphism in polar bears is among the most pronounced in the bear family.

Adult males weigh between 900 and 1,600 pounds, though exceptional individuals may exceed 2,200 pounds, particularly before winter when they’ve accumulated substantial fat reserves. Females typically weigh 330 to 550 pounds, roughly half the mass of males.

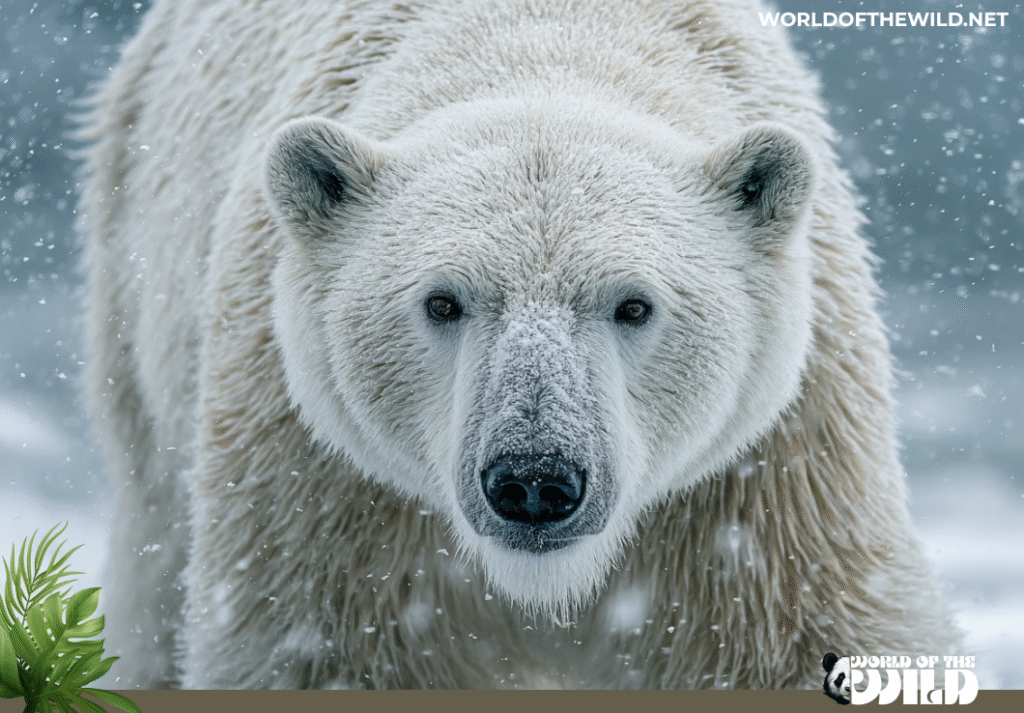

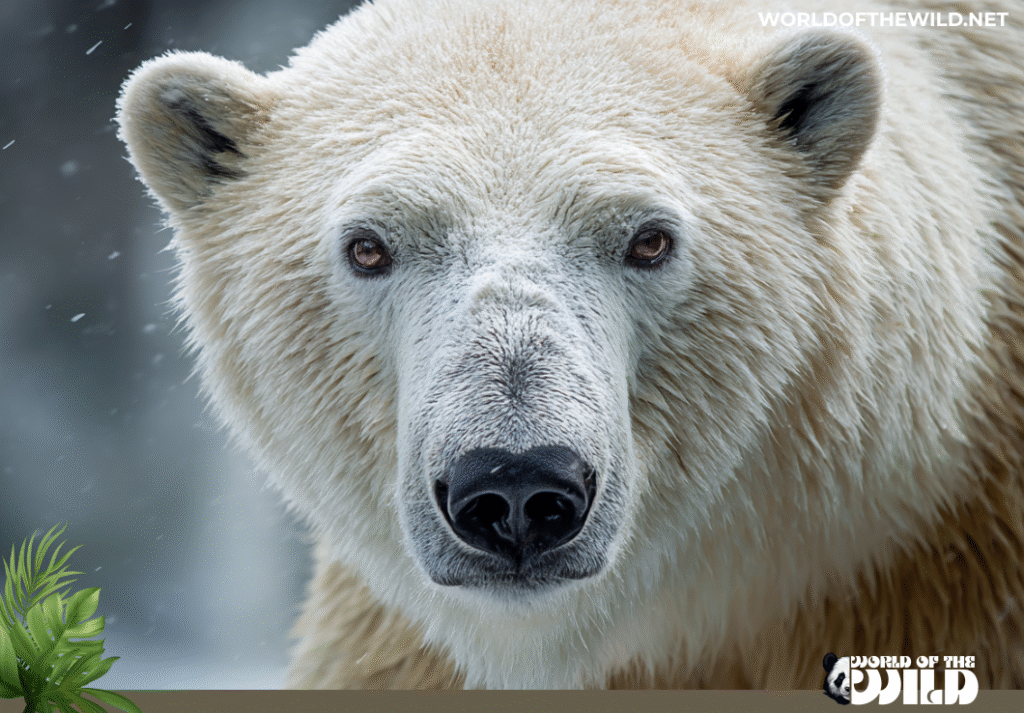

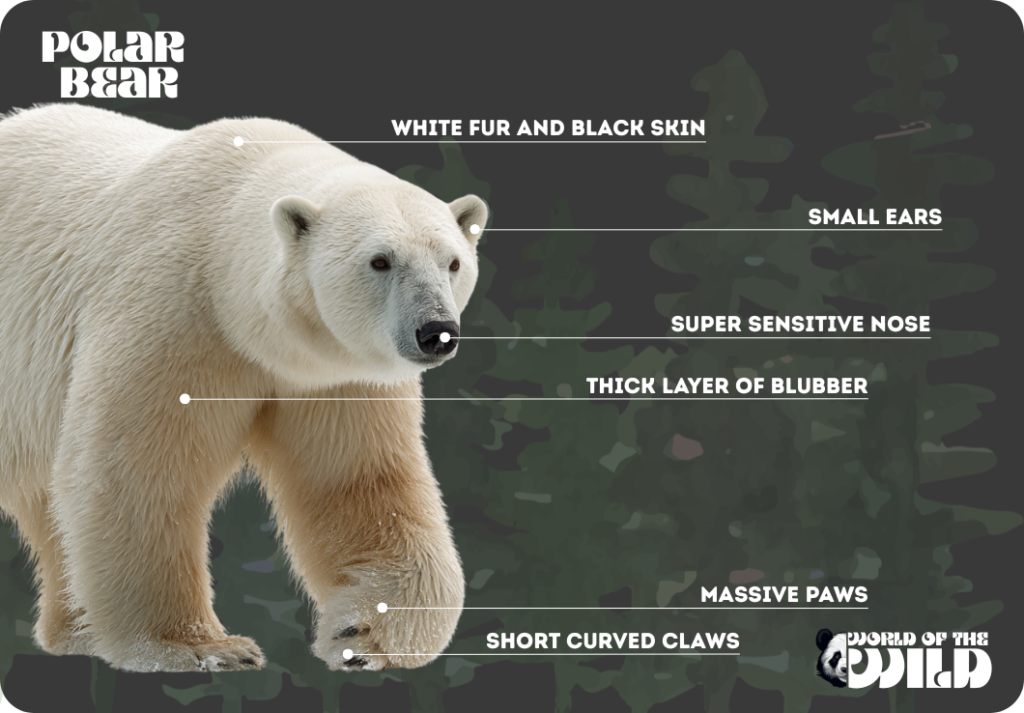

The bear’s coat appears creamy white to yellowish, often taking on a golden hue in summer sunlight due to oxidation and oils from seal prey. Each guard hair is hollow and transparent, scattering and reflecting visible light to create the white appearance while channeling ultraviolet light to the black skin beneath. The dense underfur provides additional insulation, creating an almost impenetrable thermal barrier.

Other distinctive features include a elongated head and neck, ideal for reaching seals in their breathing holes, and enormous paws measuring up to 12 inches across. These massive feet act as snowshoes, distributing the bear’s weight across thin ice and serving as powerful paddles when swimming. The paws are partially webbed, and the foot pads are covered in small, soft papillae that provide traction on ice. Sharp, curved claws measure up to 3.75 inches and are used for gripping ice and prey.

The polar bear’s small ears and short tail minimize heat loss, while its stocky build and thick layer of blubber—up to 4.5 inches thick—provide exceptional insulation against temperatures that can plummet to minus 50 degrees Fahrenheit.

Behavior

Polar bears are primarily solitary animals, with adult males and non-breeding females typically avoiding one another except during mating season. However, they are not aggressively territorial and will sometimes tolerate proximity when food is abundant, such as at whale carcasses where dozens may gather to feed.

These bears are primarily diurnal during spring and summer but can adjust their activity patterns based on prey availability and environmental conditions. They spend more than 50 percent of their time hunting, though actual hunting success rates are relatively low—only about two percent of hunts result in a kill.

The most iconic polar bear hunting technique is still-hunting at seal breathing holes. A bear will locate a breathing hole in the ice using its extraordinary sense of smell, then wait motionless for hours or even days until a seal surfaces. When the seal appears, the bear strikes with explosive speed, using its powerful forequarters to haul the 100-plus pound seal onto the ice.

Communication among polar bears involves a variety of vocalizations, body postures, and chemical signals. They produce chuffing sounds when content, hiss and growl when aggressive, and make loud roars when fighting. Mothers communicate with cubs through a variety of vocalizations, and cubs produce distress calls that bring immediate maternal response.

Polar bears demonstrate remarkable intelligence and problem-solving abilities. They’ve been observed covering their black noses with their paws while stalking seals, using blocks of ice as tools to kill prey, and cooperatively hunting walruses. They have excellent spatial memory, returning to productive hunting areas year after year and remembering the locations of dens across vast territories.

Perhaps most impressive is their swimming ability. Polar bears are classified as marine mammals due to their dependence on the marine environment. They use a dog-paddle motion and can maintain a steady pace of six miles per hour in the water. Their partially webbed feet and streamlined profile make them remarkably efficient swimmers capable of crossing vast stretches of open ocean.

Evolution

The polar bear is a relatively recent evolutionary development, having diverged from brown bears between 350,000 and 6 million years ago, with most genetic evidence supporting a divergence around 500,000 to 600,000 years ago. This makes them one of the newest species of bear, specialized for a niche that only became available during the Pleistocene ice ages.

Recent genetic studies suggest polar bears descended from a population of brown bears that became isolated in Siberia during a glacial period. These ancestral bears gradually adapted to life on sea ice, developing specialized characteristics for hunting marine mammals. Interestingly, DNA evidence shows that polar bears and brown bears interbred during several periods when their ranges overlapped, contributing to genetic diversity in both species.

The evolutionary transition from terrestrial brown bear to marine-adapted polar bear required numerous significant adaptations. These included the development of water-repellent fur, enlarged paws for swimming and ice travel, a more elongated body profile for swimming efficiency, and profound metabolic changes that allow polar bears to process a diet consisting almost entirely of fat-rich seal blubber.

Fossil evidence of polar bear ancestors is sparse, partly because their Arctic habitat is not conducive to fossil preservation. The oldest known polar bear fossil dates to approximately 130,000 to 110,000 years ago, discovered in Svalbard, Norway. This specimen already displayed characteristics typical of modern polar bears, suggesting the species evolved its distinctive features relatively rapidly in evolutionary terms.

The polar bear’s rapid evolution and specialization for Arctic conditions now poses challenges as their environment changes. Having evolved such specific adaptations to ice-based hunting, they lack the flexibility of their more generalist brown bear cousins.

Habitat

Polar bears inhabit the circumpolar Arctic region, with their range extending across five nations: Canada, the United States (Alaska), Russia, Greenland (Denmark), and Norway (Svalbard archipelago). However, calling them truly “terrestrial” is misleading—polar bears are primarily creatures of the sea ice, spending the majority of their lives on frozen ocean surfaces rather than on land.

Their preferred habitat is the annual ice over the continental shelf and the Arctic inter-island archipelagos, where the ice is dynamic and repeatedly forms cracks, leads, and polynyas—areas of open water surrounded by ice. These areas are crucial because they’re where seals surface to breathe, providing prime hunting opportunities. Polar bears show particular preference for ice at the interface between land and sea, where ice dynamics create the most productive seal habitat.

The Arctic sea ice environment is one of extremes. Winter temperatures can plummet to minus 50 degrees Fahrenheit, while summer brings 24-hour daylight and temperatures occasionally rising above freezing. The ice itself is constantly moving, driven by winds and currents, requiring polar bears to be perpetual nomads following their frozen platform.

Different subpopulations occupy distinct regions with varying characteristics. Some live on multiyear pack ice that persists through summer, while others inhabit seasonal ice zones where they must retreat to land when ice melts completely. Bears in areas like Hudson Bay are forced ashore for several months each year when the bay ice melts, surviving on fat reserves accumulated during winter and spring hunting.

Pregnant females require access to denning habitat—typically snowdrifts along coastal areas or on sea ice—where they excavate maternity dens. These dens provide crucial protection for newborn cubs during their first months of life.

As climate change reduces sea ice extent and duration, polar bears are spending increasing time on land, bringing them into greater contact with human communities and forcing them to survive on terrestrial food sources that cannot sustain their energy requirements.

Diet

Polar bears are hypercarnivorous, meaning their diet consists of more than 70 percent meat—in fact, they may be the most carnivorous bear species, with some individuals eating almost exclusively animal matter. They are specialized predators of ice-associated seals, which form the cornerstone of their diet throughout most of their range.

Ringed seals are the primary prey species, comprising the bulk of polar bear diet across the Arctic. These relatively small seals (weighing 100 to 150 pounds) maintain breathing holes in the ice, making them accessible to patient hunters. Bearded seals, which are significantly larger (500 to 800 pounds), are the second most important prey species. A single bearded seal can provide substantially more nutrition than a ringed seal, though they are more difficult to catch.

Polar bears also prey on harp seals, hooded seals, and ribbon seals when available. Opportunistic predation on walruses occurs, though these formidable prey animals are dangerous and typically only young, weak, or dead individuals are consumed. Beluga whales and narwhals trapped in ice pockets occasionally fall victim to polar bears, and the bears will readily scavenge bowhead whale carcasses.

The hunting strategy varies by season and ice conditions. During spring, when seal pups are born, bears enjoy their most abundant feeding period, preying on naïve pups in snow lairs. This is when polar bears accumulate the fat reserves that must sustain them through leaner periods.

Polar bears display a strong preference for seal blubber, which is energy-dense and easier to digest than protein-heavy muscle tissue. An adult bear requires roughly 4.4 pounds of fat per day to meet its energy needs, though they can consume over 150 pounds of food in a single feeding session when prey is available.

When ice-dependent seals are unavailable, polar bears demonstrate opportunistic feeding behaviors. They consume bird eggs, seabirds, small mammals like Arctic foxes and lemmings, vegetation including berries and kelp, and even garbage in communities where human-bear interactions occur. However, these terrestrial food sources cannot provide sufficient calories to maintain healthy body condition over extended periods.

Predators and Threats

As the apex predator of the Arctic, adult polar bears have virtually no natural predators. Their size, power, and aggressive nature when threatened make them formidable opponents for any potential challenger. However, young cubs face predation risks from adult male polar bears, which occasionally practice infanticide, particularly when females with cubs encounter males during the breeding season. Wolves have also been documented killing polar bear cubs in areas where their ranges overlap.

The greatest threats to polar bears are anthropogenic—caused by human activities. Climate change stands as the most significant threat, fundamentally altering the Arctic ecosystem upon which polar bears depend. Rising global temperatures are reducing sea ice extent, thickness, and duration. The ice is forming later in autumn and breaking up earlier in spring, shortening the critical hunting season when polar bears accumulate the fat reserves necessary for survival.

Between 1979 and present, Arctic sea ice extent has declined by approximately 13 percent per decade. Some models predict that the Arctic could experience ice-free summers within decades, which would be catastrophic for polar bear populations dependent on ice for hunting seals.

This loss of sea ice forces bears to fast for longer periods, swim greater distances between ice floes—resulting in increased drowning incidents, particularly among cubs—and spend more time on land where adequate food sources are unavailable. Research shows that bears in several subpopulations have declining body conditions, reduced cub survival, and smaller adult sizes compared to previous decades.

Pollution represents another serious threat. Polar bears accumulate high levels of persistent organic pollutants and heavy metals through their position at the top of the Arctic food web. These contaminants, which biomagnify through the food chain, can affect immune function, reproduction, and hormone systems. Mercury levels in polar bear tissues have been increasing, linked to both industrial emissions and climate-related changes in mercury cycling.

Oil and gas development in the Arctic poses risks through habitat disturbance, potential oil spills, and increased shipping traffic. An oil spill in ice-covered waters would be particularly devastating, as oil matting the bear’s fur would destroy its insulating properties, potentially leading to hypothermia.

Human-bear conflicts are increasing as bears spend more time on land near communities, searching for food. While Indigenous peoples have historically coexisted with polar bears, the combination of increased bear presence on land and growing human populations creates dangerous situations. Conflict often results in bears being killed to protect human safety.

Sport hunting, though regulated, remains controversial. Canada, while protective of polar bears, allows limited hunting by Indigenous peoples and licensed sport hunting. The sustainability of these harvests under changing environmental conditions is debated.

Reproduction and Life Cycle

Polar bears have one of the lowest reproductive rates among mammals, which makes population recovery from declines extremely slow. Sexual maturity is reached at four to five years of age for females and six years for males, though males typically don’t successfully breed until they’re eight to ten years old and large enough to compete with other males.

The breeding season occurs from late March through May, when males actively search for receptive females. Males locate females by following scent trails across vast distances, sometimes traveling over 60 miles to find a mate. When multiple males encounter a female, intense competition ensues, with larger, older males typically winning breeding rights through intimidation or combat.

Mating pairs remain together for several days to a week, mating multiple times. Polar bears exhibit delayed implantation—while fertilization occurs during spring mating, the embryo does not implant in the uterine wall until autumn, around September or October. This delay allows females to assess their body condition and environmental factors before committing to pregnancy. If a female has not accumulated sufficient fat reserves, the embryo may not implant, and pregnancy will not proceed.

Pregnant females enter maternity dens between late October and December, typically in areas with deep snow accumulation. Dens are excavated into snowdrifts on land or sometimes on sea ice, creating an insulated chamber where temperatures can be 40 degrees warmer than outside. The female will not eat, drink, defecate, or urinate during the entire denning period, which lasts three to five months.

Cubs are born between late November and early January after a gestation period of about 60 to 65 days post-implantation (though total time from mating is eight months). Litter sizes range from one to four cubs, with two being most common. At birth, cubs are remarkably underdeveloped—blind, deaf, toothless, and weighing only one to two pounds. They’re covered in fine fur but are entirely dependent on their mother.

Cubs nurse on milk containing up to 35 percent fat, one of the richest milks produced by any terrestrial mammal. They grow rapidly in the den, and by the time the family emerges in late March or April, cubs weigh 20 to 30 pounds. The mother has not eaten for up to eight months and may have lost 45 percent of her body weight.

Families remain together for two to three years, with cubs learning essential survival skills from their mothers, including hunting techniques, ice navigation, and den site selection. Female cubs often establish home ranges overlapping their mother’s territory, while males disperse further.

The inter-birth interval is typically three years, as females won’t mate again while caring for dependent young. This means a female might produce only five litters during her reproductive lifetime, making each reproductive event crucial for population maintenance.

In the wild, polar bears live approximately 15 to 18 years on average, though some individuals reach 30 years. Captive bears typically live longer, with lifespans of 35-plus years documented. Males generally have shorter lifespans than females, partly due to the physical toll of fighting during breeding season and generally riskier behavior.

Population

The polar bear is currently classified as Vulnerable on the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List of Threatened Species. This classification reflects concerns about long-term population viability due to climate change impacts on sea ice habitat.

Global population estimates are challenging due to the polar bear’s remote habitat and wide-ranging behavior, but the best current estimate places the worldwide population at approximately 26,000 individuals, with a plausible range of 22,000 to 31,000. This population is distributed across the previously mentioned 19 subpopulations, which show varying trends.

Population trends differ significantly by subpopulation based on regional ice conditions and other factors. Some subpopulations are stable, some are increasing, but several are declining. The Southern Beaufort Sea subpopulation has shown documented declines, dropping from around 1,500 bears in 2001-2006 to approximately 900 in recent counts. The Western Hudson Bay population has also declined by approximately 30 percent over the past three decades, with bears coming ashore earlier and in poorer condition.

Other subpopulations in areas with more stable ice conditions, such as the Davis Strait population, have remained relatively stable or even increased in recent years, though long-term viability remains uncertain as climate change progresses.

Population monitoring is complicated by the fact that declines may be delayed relative to ice loss. Polar bears can buffer the effects of reduced ice access by relying on accumulated fat reserves, meaning population impacts may not become apparent for years or even decades after habitat degradation begins.

Projections for future populations are concerning. Scientific models suggest that if current greenhouse gas emission trends continue, polar bear numbers could decline by more than 30 percent over the next 35 to 40 years. Some models predict more dramatic declines, with certain subpopulations potentially becoming extinct within this century if summer sea ice disappears from their ranges.

The species is protected under various international and national regulations. The 1973 International Agreement on the Conservation of Polar Bears and their Habitat, signed by all five polar bear range states, was a landmark conservation treaty. Polar bears are listed on Appendix II of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES), regulating international trade. In the United States, polar bears are listed as Threatened under the Endangered Species Act.

Conclusion

The polar bear stands as one of nature’s most magnificent achievements—a creature so perfectly adapted to its frozen world that it reigns unchallenged as the Arctic’s supreme predator. From its hollow, heat-channeling fur to its remarkable ability to fast for months while nursing cubs, every aspect of the polar bear reflects millions of years of evolutionary refinement for a life among the ice.

Yet this same specialization now threatens the species’ survival. As we’ve seen, polar bears are not merely animals living in the Arctic; they are animals of the ice itself, dependent on frozen seas for their very existence. The accelerating loss of sea ice transforms their frozen kingdom into open ocean, eroding the platform upon which their entire life strategy depends. Young cubs drown attempting swims their ancestors never had to make. Mothers emerge from dens unable to reach the seals that would replenish their depleted bodies. Bears wander into human communities, desperately seeking food on land that cannot sustain them.

The polar bear’s fate is being written not in the Arctic but in our cities, our power plants, our choices. They cannot adapt to the rapid pace of change; evolution does not work on human timescales. If we are to ensure that future generations can marvel at these magnificent creatures prowling the northern ice—rather than viewing them as cautionary tales in history books—the time for meaningful action on climate change is now. The polar bear asks nothing of us except that we preserve the frozen world that made them possible. The question is whether we will answer that call before the ice, and the bears, are gone.

Scientific Name: Ursus maritimus

Diet Type: Carnivore (Hypercarnivore)

Size: Males: 7.9-9.8 feet in length; Females: 5.9-7.9 feet in length

Weight: Males: 900-1,600 pounds; Females: 330-550 pounds

Region Found: Circumpolar Arctic (Canada, United States/Alaska, Russia, Greenland/Denmark, Norway/Svalbard)