Introduction

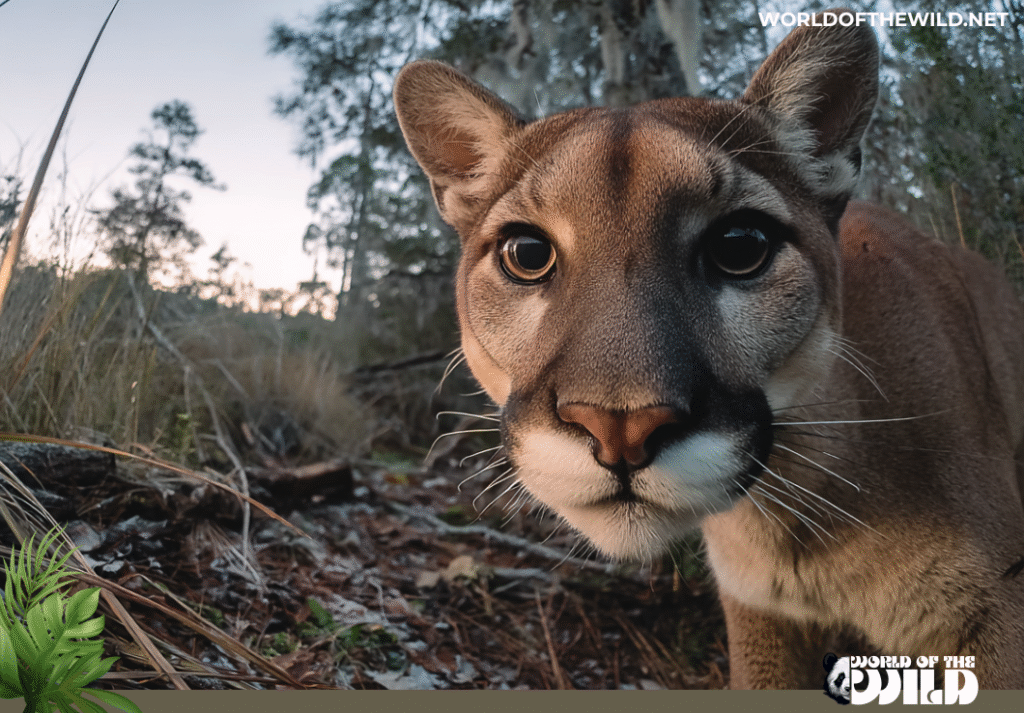

Imagine a ghost moving through the dense cypress swamps and thick pinelands of South Florida, an apex predator whose presence is felt more than it is seen. This phantom of the forest is the Florida Panther (Puma concolor coryi), the last remaining big cat in the eastern United States. With its piercing eyes and muscular frame, it embodies the wild, untamed spirit of the Everglades and Big Cypress ecosystems.

This animal is not just fascinating; it is profoundly significant as a crucial umbrella species. By protecting the panther and its vast habitat, we inadvertently protect countless other plant and animal species that share its range, making its survival a barometer for the health of Florida’s most precious natural areas. Its story is one of dramatic decline, a heroic comeback, and an ongoing fight for its rightful place in the wilderness.

Facts

Here are a few quick facts that showcase the Florida Panther’s unique nature:

- Spotless Kittens: Panther kittens are born with dark spots that provide excellent camouflage in their dens, but they lose these spots as they mature, developing the uniform tawny color of an adult.

- A Kinked Tail and Cowlick: Almost all Florida Panthers have a distinctive, harmless kink at the end of their tail and a whorl of fur, or “cowlick,” in the middle of their back—traits caused by inbreeding before conservation efforts intervened.

- Sound of a Squeak: Unlike the “true” big cats (lions, tigers, jaguars, and leopards) in the genus Panthera, panthers (which are technically cougars/mountain lions) cannot roar. They communicate through a variety of calls, including chirps, purrs, hisses, growls, and an almost bird-like peep or squeak.

- Long-Distance Travelers: A single male panther can have a home range of 200 square miles or more (over $500 \text{ km}^2$), necessitating the protection of vast, interconnected tracts of land.

- Record Holders: A male panther can jump up to 15 feet (nearly 4.6 meters) horizontally and are known for their powerful sprint, though they are ambush predators and not built for long chases.

Sounds of the Florida Panther

Species

The Florida Panther is a distinct subspecies of a widely distributed New World cat.

| Classification Level | Scientific Name |

| Kingdom | Animalia |

| Phylum | Chordata |

| Class | Mammalia |

| Order | Carnivora |

| Family | Felidae |

| Genus | Puma |

| Species | Puma concolor |

| Subspecies | Puma concolor coryi |

The Florida Panther (Puma concolor coryi) is one of several subspecies of the cougar (Puma concolor), which is also known as the mountain lion, catamount, or simply “panther” across its immense range from Canada to South America. All these names refer to the same species, with the Florida Panther being the only population remaining in the eastern US. It is most closely related to the cougar populations of the Western Hemisphere.

Appearance

The Florida Panther is a medium-sized cat, significantly smaller than the South American jaguar, but larger than the bobcat.

- Size and Weight: Males are larger, typically measuring 7 feet (about 2.1 meters) from nose to tail tip and weighing between 100 and 160 pounds (45–72 kg). Females are smaller, averaging about 6 feet (1.8 meters) long and weighing 65 to 100 pounds (30–45 kg).

- Coloration: Their coat is uniformly tawny, beige, or rusty brown across the back, with a creamy white or buff underside. This coloration provides excellent camouflage in the shadows and sawgrass of their environment.

- Distinctive Features: The most notable features include their small head, large paws, and a relatively long, thick tail which aids in balance when running or jumping. As mentioned earlier, many have a characteristic kink at the tip of the tail and a whorl of fur on the back, used by researchers to help identify individuals. They have sharp, amber-colored eyes and powerful, muscular legs built for explosive acceleration.

Behavior

Florida Panthers are famously solitary and nocturnal animals.

- Daily Life: They are most active at dawn and dusk (crepuscular) but may hunt throughout the night, using the day to rest and groom in dense cover. They are highly territorial, especially males, who use scent markings (scrapes and urine) and vocalizations to communicate their presence and avoid confrontation.

- Social Structure: Interactions are generally limited to breeding, or a mother raising her kittens. They are exceptionally elusive and avoid humans, with attacks on people being virtually unheard of.

- Intelligence and Adaptation: Their behavior showcases high intelligence, particularly in their mastery of stealth. They are highly effective ambush predators, relying on camouflage and patience to stalk prey before a sudden, powerful attack. They are also known to be able to swim across canals and swamps, a necessary adaptation for navigating the watery landscape of the Everglades.

Evolution

The Florida Panther shares its evolutionary history with the larger cougar species (Puma concolor).

- Ancestry: Cougars are part of the Felinae subfamily, which split off from the “true big cats” (Pantherinae) about 6.7 million years ago. The ancestors of modern cougars migrated into North America approximately 8 to 9 million years ago.

- Global Extinction Event: Around 10,000 years ago, at the end of the last Ice Age, a massive extinction event wiped out many large mammals in North America, including other large cat species like the American lion and the saber-toothed cat. Genetic evidence suggests that all modern North American cougars descended from a small population of cougars that survived this event, likely in a southern refuge.

- Subspecies Isolation: The Florida Panther evolved into a distinct subspecies due to geographic isolation in the southeastern swamps and forests. For centuries, this isolation led to the development of unique genetic traits (and unfortunately, in the 20th century, severe inbreeding issues). Conservation efforts in the 1990s introduced eight female cougars from Texas to restore genetic diversity, a move that genetically “rescued” the subspecies.

Habitat

The Florida Panther’s geographic range has been drastically reduced but is intensely protected in the southern part of the state.

- Geographic Range: Historically, panthers roamed across the entire southeastern U.S. Today, the only confirmed breeding population is restricted to a small area of South Florida, south of the Caloosahatchee River.

- Specific Environment: The panther is a habitat generalist, but it prefers large, connected tracts of forested uplands (like pine flatwoods and hardwood hammocks) for denning and resting, which are often interspersed with freshwater marshlands, cypress swamps, and sawgrass prairies for hunting. The crucial element is the size and connectivity of the habitat, as each cat requires a vast, uninterrupted range to thrive.

Diet

The Florida Panther is an obligate carnivore—it eats only meat.

- Primary Food Sources: The majority of their diet consists of white-tailed deer and feral hogs (wild pigs), which are their preferred and most common large prey.

- Secondary Food Sources: They also opportunistically prey on smaller animals, including raccoons, armadillos, rabbits, alligators, and birds.

- Hunting: Panthers hunt by stealth and ambush. They stalk their prey, often for a long time, using thick cover to get as close as possible before making a rapid, fatal leap, typically aiming for the neck or head. They usually drag their kill to a hidden spot and may feed on it for several days, covering the carcass with vegetation between meals to protect it from scavengers.

Predators and Threats

As an apex predator, the adult Florida Panther has virtually no natural predators.

- Natural Predators: The only animals that pose a threat are large alligators, which may occasionally prey on kittens, or other, larger male panthers who may attack smaller individuals over territory.

- Anthropogenic Threats (Human-Caused): The biggest threats are entirely human-caused, and they are severe:

- Habitat Loss and Fragmentation: This is the number one threat. Development, agriculture, and urban sprawl continually chew away at and break up the forests and swamps the panthers need.

- Vehicle Collisions (Road Mortality): Panthers are frequently killed trying to cross busy South Florida roads and highways that slice through their territories, making this the leading cause of death.

- Inbreeding and Disease: While genetic rescue helped, the tiny population remains vulnerable to genetic defects and disease outbreaks like the Feline Leukemia Virus (FeLV) or the unknown neurological disorder that has recently affected some panthers.

Reproduction and Life Cycle

Panthers typically reach sexual maturity around two to three years old.

- Mating: Mating can occur year-round, but a peak is seen in late fall to early winter. A male may associate with a female for several days during courtship.

- Gestation: The gestation period is approximately 90 to 95 days.

- Offspring: A female gives birth to a litter of one to four spotted kittens in a den made in a thicket, under a fallen tree, or in dense saw palmetto.

- Parental Care: The mother is the sole caretaker, aggressively protecting the kittens and weaning them at about 10 weeks. They will remain with her, learning to hunt and survive, for up to 1.5 to 2 years before dispersing to find their own territory.

- Lifespan: The average lifespan in the wild is around 12 to 15 years, though some individuals have been documented living slightly longer.

Population

The conservation story of the Florida Panther is a testament to the power of human intervention.

- Conservation Status: The Florida Panther is listed as Endangered under the U.S. Endangered Species Act.

- Global Population: Due to intensive conservation and genetic rescue efforts, the population has slowly recovered from a historical low of fewer than 20 individuals in the 1970s. The current population estimate is between 120 and 230 adult and subadult panthers in the wild.

- Population Trends: The trend is currently stable or slightly increasing, a hard-won victory for conservationists. However, the population is not biologically recovered, and they have not successfully established a second breeding population outside of South Florida, a key goal for their de-listing. The limited size of the population makes them perpetually vulnerable to major threats.

Q and A

Q. What is the Lifecycle of a Florida Panther?

A. The lifecycle of a Florida panther is a journey of transition from a vulnerable, spotted kitten to a solitary, wide-ranging apex predator. On average, they live 8 to 12 years in the wild, though some reach their late teens.

The process is generally broken down into the following stages:

1. Birth and Infancy (0–2 Months)

- Gestation: After a mating season that peaks between November and March, females give birth following a 90 to 95-day pregnancy.

- The Den: Kittens (usually 1 to 3 per litter) are born in dense saw palmetto thickets or scrub.

- Appearance: At birth, kittens are blind and weigh only about 1 pound. They have blue eyes and dark spots on their fur—camouflage that mimics the dappled sunlight of the forest floor to hide them from predators while their mother hunts.

- Nursing: They rely entirely on their mother’s milk for the first 6–8 weeks.

2. The Learning Phase (2–18 Months)

- Leaving the Den: Around 2 months old, kittens begin to follow their mother and eat meat.

- Physical Changes: By 6 months, their spots begin to fade, and their blue eyes turn golden-brown or hazel.

- Hunting Skills: At 9 months, they start hunting small prey (like raccoons or armadillos) on their own. However, they still rely on their mother for protection and larger kills, like deer or feral hogs.

3. Dispersal and Adolescence (1.5–3 Years)

- Independence: Between 18 and 24 months, young panthers leave their mother. This is the most dangerous time in their lives.

- Seeking Territory: * Females often stay close to their mother’s home range.

- Males (the “dispersers”) may travel over 100 miles to find their own territory, often crossing dangerous highways.

- Sexual Maturity: Females are ready to breed at about 2 years old, while males typically wait until they are 3 years old and have established a territory.

4. Adulthood (3+ Years)

- Solitary Life: Adults are highly territorial and solitary. A single male’s territory (up to 200 square miles) may overlap with those of several females.

- Reproduction: Females typically have a litter every two years. If a litter is lost early, she may breed again sooner.

Comparison of Male vs. Female Lifecycles

| Feature | Female Panther | Male Panther |

| Maturity | ~2 years | ~3 years |

| Territory Size | ~75 sq. miles | ~200 sq. miles |

| Dispersal | Stays near birth site | Travels long distances |

| Parental Role | Sole provider for kittens | None (may even be a threat to kittens) |

Conclusion

The Florida Panther, the shadow of the Sunshine State, is a powerful symbol of successful conservation but also a stark reminder of the sacrifices required to protect what little wilderness we have left. From their distinguishing tail-kinks to their elusive, nocturnal hunts, they embody the last wild heartbeat of the American Southeast.

The panther’s future is inextricably tied to ours. As development continues to pressure their small range, every mile of protected land and every wildlife underpass built offers them a chance at survival. We must remain committed to safeguarding the vast, interconnected ecosystems they need—for when the panther thrives, so too does the wild heart of Florida. Its fate rests not in the swamps, but in our hands.

Hungry for More? The hunt doesn’t end here. Dive into our complete collection of Big Cat guides and articles.