In the frigid, dark waters of the North Pacific and Bering Sea, a creature of remarkable proportions scuttles across the ocean floor, its spiny legs spanning wider than a bicycle wheel. The Alaskan King Crab, with its formidable appearance and impressive size, has captivated commercial fishermen, seafood enthusiasts, and marine biologists alike. These armored giants are far more than just a delicacy on dinner plates—they are evolutionary marvels that have adapted to thrive in one of Earth’s harshest marine environments. From their complex molting processes to their epic migrations across the seafloor, king crabs represent a fascinating intersection of biological adaptation, ecological importance, and economic significance that makes them one of the most compelling creatures in our oceans.

Facts

- King crabs aren’t true crabs at all—they’re more closely related to hermit crabs, which is why they have a reduced fifth pair of legs tucked inside their shell.

- A single female king crab can carry between 50,000 to 500,000 eggs at once, which she protects beneath her abdomen for nearly a year before they hatch.

- King crabs can regenerate lost limbs over successive molts, though the new limb may be smaller than the original until multiple molting cycles occur.

- These crustaceans communicate with each other by creating vibrations and sounds through stridulation—rubbing body parts together much like crickets do.

- During their annual migration, king crabs have been documented traveling over 100 miles from deep water to shallow breeding grounds, forming massive aggregations that can number in the thousands.

- The blue coloration of king crab blood comes from hemocyanin, a copper-based oxygen-carrying molecule, rather than the iron-based hemoglobin found in human blood.

- Individual king crabs can live for more than 30 years in the wild, though most harvested crabs are between 5 and 10 years old.

Species

Kingdom: Animalia

Phylum: Arthropoda

Class: Malacostraca

Order: Decapoda

Family: Lithodidae

Genus: Paralithodes

Species: Paralithodes camtschaticus (Red King Crab)

The term “Alaskan King Crab” actually encompasses three primary commercial species found in Alaskan waters. The Red King Crab is the largest and most economically important, recognized by its burgundy-red coloration. The Blue King Crab, found in deeper, colder waters around the Pribilof Islands and St. Matthew Island, displays a distinctive blue-brown coloration and commands premium prices due to its sweeter meat and limited availability. The Golden King Crab, also called Brown King Crab, inhabits the deepest waters along the Aleutian Islands and features a golden-orange shell with a more rounded carapace.

Beyond these three commercial species, the Lithodidae family contains over 120 species of king crabs and stone crabs distributed throughout the world’s oceans, though the largest and most iconic species remain concentrated in the North Pacific.

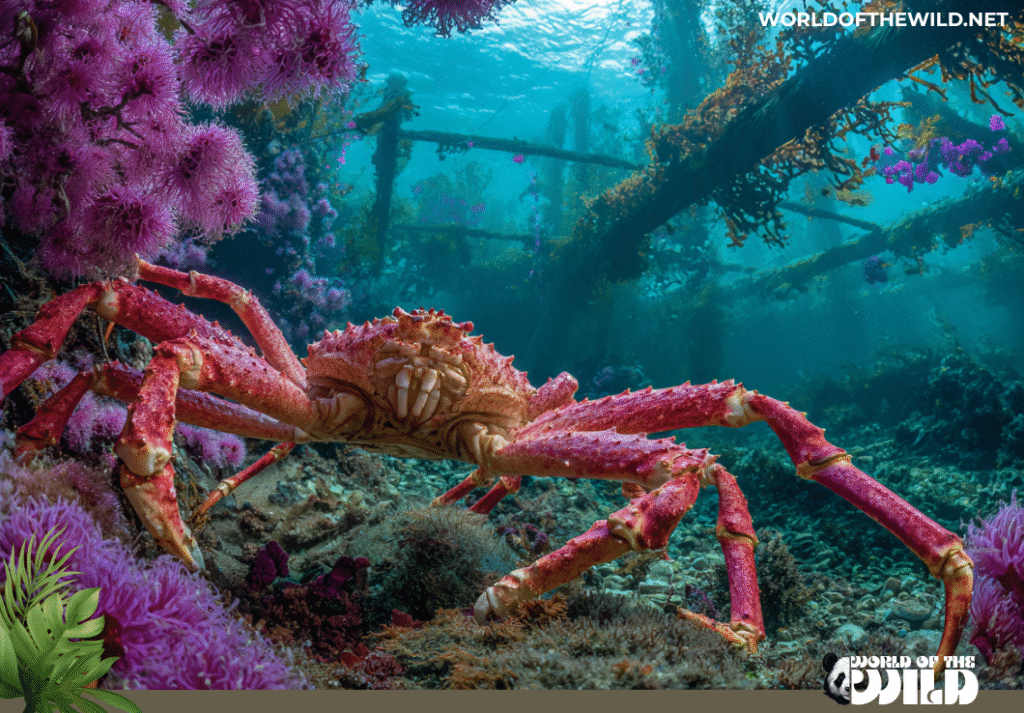

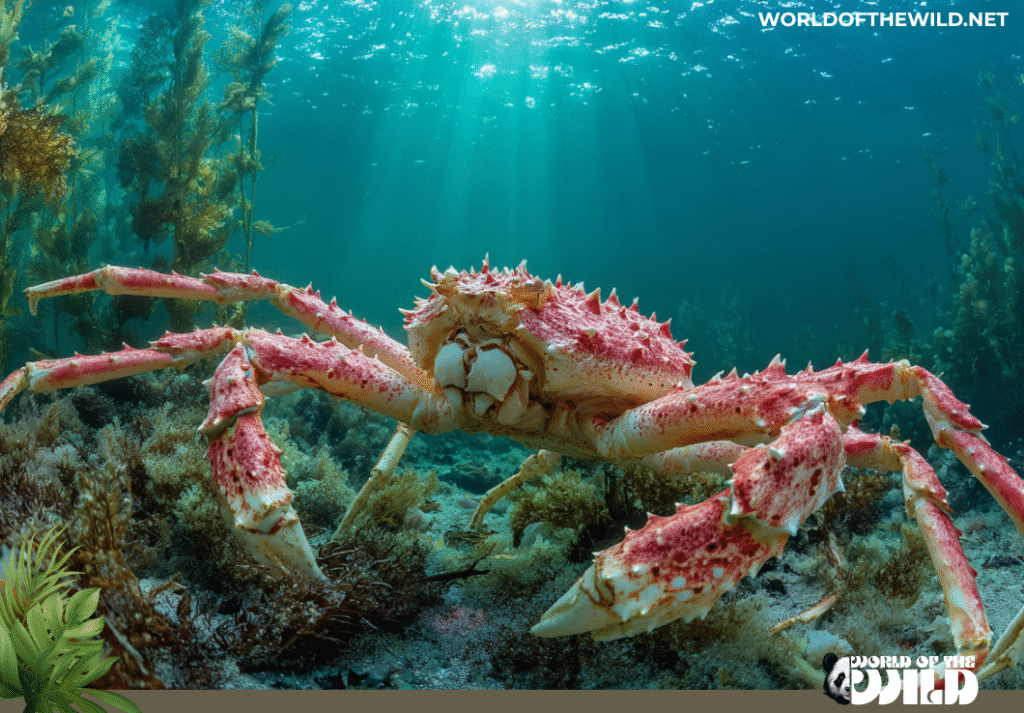

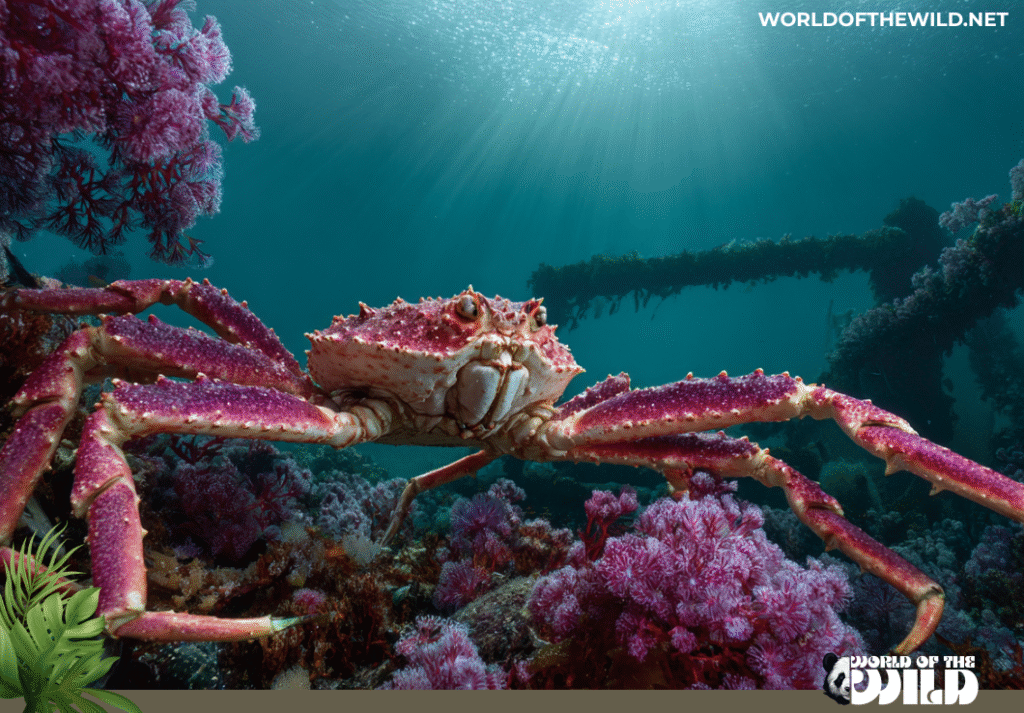

Appearance

The Alaskan King Crab is an imposing arthropod that can reach truly impressive dimensions. Red King Crabs, the largest of the species, can achieve a leg span of up to 6 feet from claw to claw, with their carapace (shell) measuring up to 11 inches across. Males substantially outsize females, with large specimens weighing between 10 to 24 pounds, though exceptional individuals have been recorded at over 28 pounds.

The crab’s exoskeleton is covered with sharp, thorn-like spines that provide protection from predators and give the animal its formidable appearance. The coloration varies by species and can change based on diet and environment, ranging from deep burgundy-red to blue-tinged brown or golden-orange. Their body is divided into the cephalothorax (fused head and thorax) and the asymmetrical, reduced abdomen that curls beneath the body.

King crabs possess five pairs of legs, though the fifth pair is significantly reduced and tucked inside the gill chamber, where it’s used to clean the gills. The first pair of legs has evolved into massive crushing claws, with the right claw typically being larger than the left. These powerful pincers can exert considerable force to crack open mollusks and other hard-shelled prey. Their remaining walking legs are long and sturdy, ending in sharp points that allow them to traverse rocky substrates and resist strong ocean currents.

The crab’s stalked eyes protrude from the carapace, providing good vision in the dim light of their deep-water habitat. Between the eyes, two pairs of antennae extend outward, serving as important sensory organs for detecting chemical signals in the water.

Behavior

Alaskan King Crabs exhibit fascinating behavioral patterns shaped by their harsh environment and life cycle demands. These creatures are primarily solitary for much of the year, spending their time foraging across the seafloor. However, they undergo dramatic behavioral shifts during migration and mating seasons, when they aggregate in massive groups called “pods” that can contain thousands of individuals moving together across the ocean floor.

King crabs are primarily nocturnal, becoming more active during nighttime hours when they forage for food while avoiding visual predators. During daylight, they often seek shelter in rocky crevices or bury themselves partially in sediment. Their movement is distinctive—they walk sideways and forward using their long, pointed legs, and can achieve surprising speed when necessary, though they typically move in a slow, deliberate manner.

Communication among king crabs involves multiple sensory channels. They produce sounds through stridulation, rubbing specialized ridges on their body parts together to create vibrations that travel through the water. They also rely heavily on chemical communication, releasing pheromones that convey information about reproductive status, identity, and territorial boundaries. During competitive encounters, males will engage in combat, using their powerful claws to grapple with rivals over territory or access to females.

One of the most remarkable behaviors is their annual migration. Adult king crabs move from deep wintering grounds to shallower coastal waters for breeding, sometimes traveling over 100 miles. These migrations are timed with seasonal changes and follow predictable routes that crabs seem to navigate using a combination of environmental cues including temperature gradients, substrate type, and possibly geomagnetic fields.

King crabs also demonstrate notable intelligence for invertebrates, showing problem-solving abilities when accessing food and exhibiting learned behaviors that help them avoid fishing gear in heavily harvested areas.

Evolution

The evolutionary history of king crabs is a subject of ongoing scientific investigation and debate. King crabs belong to the superfamily Paguroidea, making them more closely related to hermit crabs than to true crabs (Brachyura). This relationship is evident in several anatomical features, particularly their asymmetrical, reduced abdomen and the position of their fifth leg pair.

The prevailing hypothesis suggests that king crabs evolved from hermit crab ancestors that abandoned their borrowed shells and developed their own hardened exoskeleton. This evolutionary transition, called carcinization, has occurred independently in multiple crustacean lineages. The shift likely occurred during the Cenozoic Era, though precise dating remains challenging due to the limited fossil record of soft-bodied crustaceans.

Fossil evidence of lithodid crabs extends back to the Eocene epoch, approximately 40 million years ago, with specimens found in sediments that indicate these ancient relatives already occupied cold-water marine environments. The diversification of modern king crab species appears to have accelerated during the cooling of ocean temperatures in the late Cenozoic, particularly as Arctic and sub-Arctic marine ecosystems developed.

The evolution of their massive size represents an example of deep-sea gigantism, a phenomenon where cold-water species tend to grow larger than their warm-water relatives. This adaptation likely relates to the slower metabolism required in cold environments, extended lifespans, and reduced predation pressure in deep waters.

Recent molecular studies have helped clarify relationships among king crab species, revealing that the Paralithodes genus diversified relatively recently in evolutionary terms, with the separation of red, blue, and golden king crabs occurring within the last few million years as they adapted to different depth zones and geographic regions of the North Pacific.

Habitat

Alaskan King Crabs inhabit the cold waters of the North Pacific Ocean and Bering Sea, with their range extending from coastal Alaska to Russia, Japan, and Korea. The different species occupy distinct depth zones, creating vertical stratification in their distribution.

Red King Crabs are found at depths ranging from shallow intertidal zones down to about 650 feet, though they most commonly occur between 30 and 400 feet. They prefer rocky substrates, boulder fields, and areas with complex bottom topography that provides shelter and hunting grounds. During different life stages and seasons, they move between depth zones—adults migrate to shallow waters for breeding in late winter and spring, then return to deeper waters for the summer and fall.

Blue King Crabs occupy colder, deeper waters than their red cousins, typically ranging from 300 to 600 feet deep, though they’ve been found as deep as 1,400 feet. They favor muddy or sandy bottoms with scattered rocks and are more tolerant of extremely cold temperatures. Their range is more limited, concentrating around the Pribilof Islands, St. Matthew Island, and parts of the Russian coast.

Golden King Crabs inhabit the deepest waters, generally found between 600 and 1,600 feet, with some populations occurring as deep as 3,000 feet along the continental slope. They prefer rocky substrates and underwater geological features like seamounts and canyon edges. These crabs tolerate a narrower temperature range, typically between 34 and 40 degrees Fahrenheit.

The seafloor habitat where king crabs live is characterized by near-freezing temperatures, high pressure, low light conditions, and strong bottom currents. These environments feature rich invertebrate communities that provide food sources, as well as predators and competitors. The crabs require areas with adequate dissolved oxygen and specific salinity levels, making them sensitive to oceanographic changes.

Seasonal sea ice plays an important role in king crab ecology, affecting water temperature, light penetration, and the timing of primary production that fuels the broader food web supporting these crustaceans.

Diet

Alaskan King Crabs are opportunistic omnivores with a diet that shifts based on availability, season, and life stage. Their feeding strategy combines active hunting with scavenging, making them important ecosystem engineers that help recycle nutrients on the seafloor.

The primary diet of adult king crabs consists of a diverse array of organisms. They actively prey on mollusks, using their powerful crusher claw to break open clams, mussels, snails, and other hard-shelled invertebrates. Worms, both polychaetes and other marine worms, form another significant food source. They also consume other echinoderms including sea stars, brittle stars, sea urchins, and sand dollars. Smaller crustaceans, including amphipods, smaller crabs, and shrimp, are readily captured and consumed.

King crabs supplement their carnivorous diet with plant material, feeding on algae, kelp, and other marine vegetation. This omnivorous approach allows them to adapt to seasonal changes in food availability. They’re also efficient scavengers, consuming dead fish, marine mammals, and other carrion that settles to the seafloor.

Their feeding method involves using their legs to manipulate food items and their smaller claws to tear food into manageable pieces before transferring it to their mouthparts. The crusher claw can generate impressive force, easily breaking through shells that would resist many other predators. Their keen chemical sensors allow them to detect food from considerable distances, and they’ll travel substantial distances to reach promising feeding areas.

Juvenile king crabs have somewhat different dietary preferences, focusing more heavily on small invertebrates, detritus, and diatoms until they grow large enough to tackle harder-shelled prey. This dietary shift reflects their increasing jaw and claw strength as they mature.

Predators and Threats

Despite their formidable size and armored appearance, Alaskan King Crabs face predation throughout their life cycle. The most vulnerable stages are the larval and juvenile phases, when mortality rates exceed 99 percent. During these early stages, countless marine predators consume king crab larvae and small juveniles, including fish such as Pacific cod, halibut, and various rockfish species, as well as other crabs, sea stars, and octopuses.

As king crabs grow larger, the number of predators capable of tackling them decreases significantly. Adult king crabs still face predation from Pacific octopuses, which can overcome even large crabs by using their flexibility to access vulnerable joints in the crab’s armor. Large Pacific halibut and various shark species will consume adult king crabs when encountered. Sea otters, where their populations overlap with king crab habitat, are capable predators that can manipulate and crack open even large specimens.

Human fishing represents by far the most significant source of mortality for adult king crabs. Commercial fishing operations targeting king crabs have operated in Alaskan waters since the 1950s, with annual catches fluctuating dramatically based on population cycles and management regulations. Overfishing during the 1970s and 1980s led to catastrophic population crashes in several regions, particularly affecting blue king crab stocks that remain depressed today.

Beyond direct harvest, king crabs face numerous anthropogenic threats. Climate change impacts their habitat through warming ocean temperatures, which can stress these cold-adapted species and alter the timing of critical life-cycle events. Ocean acidification, caused by increased carbon dioxide absorption, threatens the crab’s ability to build and maintain their calcium carbonate exoskeletons. Changes in sea ice extent and timing affect the productivity of Arctic marine ecosystems, potentially reducing food availability.

Bycatch in fisheries targeting other species claims additional crabs, though regulations have improved selectivity. Habitat degradation from bottom trawling damages the complex seafloor structures that provide shelter and foraging grounds. Marine pollution, including plastic debris and chemical contaminants, poses emerging threats to crab health and reproductive success.

Reproduction and Life Cycle

The reproductive cycle of Alaskan King Crabs is a complex, multi-year process that demonstrates remarkable adaptations to their challenging environment. Sexual maturity is reached relatively late in life—males typically mature at 5 to 7 years of age, while females mature slightly earlier at 4 to 6 years. The timing of maturity corresponds with reaching adequate size, generally a carapace width of 4 to 5 inches.

Mating occurs annually during late winter to early spring, following the crabs’ migration to shallow waters. The courtship involves males competing intensely for access to females, engaging in combat where they grapple with their large claws, with dominant males securing mating opportunities. When a male successfully courts a female, he will grasp her and may carry her for several days in a behavior called “the clutch” while waiting for her to molt. Mating can only occur immediately after the female molts, while her new shell is still soft.

During copulation, which may last several hours, the male deposits sperm into the female’s seminal receptacle, where it will be stored. Females can retain viable sperm for over a year, allowing them to fertilize multiple egg batches without additional mating. Shortly after mating, females extrude between 50,000 and 500,000 eggs, which are immediately fertilized by the stored sperm. These eggs attach to specialized hairs on the underside of the female’s abdomen, where she will carry and protect them for 11 to 12 months.

Egg development is slow in the cold waters, progressing through several stages that can be observed by color changes in the egg mass. Females provide active maternal care, regularly grooming the eggs and fanning them with swimming movements to ensure adequate oxygen circulation. This extended brooding period, one of the longest among crustaceans, represents a significant investment but increases offspring survival.

Hatching occurs the following spring, typically from February to April, releasing tiny larvae called zoea into the water column. These microscopic larvae bear little resemblance to adult crabs, instead appearing more like tiny swimming shrimp. They undergo four zoeal stages over approximately two months, during which they drift with ocean currents while feeding on phytoplankton and other microscopic organisms.

Following the zoeal stages, larvae molt into a glaucothoe stage—a transitional form that begins to resemble a tiny crab. These glaucothoe larvae eventually settle to the seafloor, undergoing a final molt into the first juvenile crab stage. Settlement typically occurs in nearshore areas with rocky substrate or shell hash that provides protection from predators.

Juvenile crabs face extraordinarily high mortality—estimates suggest less than one percent survive from hatching to their first year. Those that survive grow rapidly, molting frequently as they increase in size. Molting becomes less frequent with age; adults may molt only once per year or even less frequently. During each molt, the crab increases substantially in size, sometimes growing 50 percent larger in a single molting event.

The lifespan of king crabs in the wild can exceed 30 years, though most individuals are harvested by commercial fisheries before reaching maximum age. Females can reproduce annually once mature, potentially producing millions of larvae over their lifetime, though actual reproductive output varies with food availability, environmental conditions, and individual health.

Population

The conservation status and population dynamics of Alaskan King Crab species vary considerably among the three main commercial species. Red King Crab populations are generally considered stable in most of their range, though they’re managed under strict quotas to prevent the overharvest that devastated stocks in past decades. The Alaska Department of Fish and Game does not assign these species an endangered status classification, instead managing them as commercial fishery resources.

The Blue King Crab, however, tells a different story. Populations around St. Matthew Island collapsed in the 1990s and have not recovered, leading to complete fishery closures. The Pribilof Islands population remains severely depressed, supporting only limited subsistence harvest. Scientists estimate that blue king crab populations are at a fraction of their historical abundance, though exact global population figures are difficult to determine due to their deep-water habitat and wide distribution.

Red King Crab populations in Bristol Bay fluctuate considerably but have shown resilience under modern management practices. The most recent stock assessments estimate the mature male biomass in Bristol Bay at several tens of thousands of metric tons, supporting annual harvests that vary from zero in poor years to tens of millions of pounds when populations are robust. These dramatic fluctuations appear to be linked to environmental conditions affecting larval survival, creating strong and weak year classes that pulse through the population.

Golden King Crab populations in the Aleutian Islands appear relatively stable, supporting a sustainable fishery with annual catches typically ranging from 5 to 7 million pounds. Their deep-water habitat has provided some protection from overharvest, though they face increasing pressure as other king crab fisheries remain restricted.

Management of king crab populations represents one of the most sophisticated fishery management systems in the world. Regulations include seasonal closures timed to protect breeding aggregations, size limits that ensure crabs can reproduce before harvest, sex-based restrictions that prohibit taking females entirely, quotas based on scientific stock assessments, and gear restrictions that reduce bycatch. Despite these measures, populations remain vulnerable to environmental changes that affect recruitment, and the legacy of past overharvesting continues to impact population structure.

Long-term monitoring suggests that climate change poses an emerging threat to population stability, with warming waters potentially favoring range expansions northward while making southern portions of their range less suitable. The interaction between fishing pressure, environmental variation, and climate change will likely determine the future trajectory of king crab populations.

Conclusion

The Alaskan King Crab stands as a testament to the remarkable adaptations that allow life to flourish in Earth’s most challenging marine environments. From their evolutionary origins as hermit crab relatives to their current status as ecosystem engineers and commercially valuable species, these armored giants embody the complexity and resilience of cold-water marine ecosystems. Their elaborate life cycle, impressive migrations, and important ecological roles as both predators and prey make them far more than a seafood commodity—they are integral components of North Pacific marine biodiversity.

Yet the story of king crabs also serves as a cautionary tale about the consequences of overexploitation and the ongoing challenges posed by climate change. The collapse of blue king crab populations and the volatile nature of red king crab stocks demonstrate how quickly even abundant species can decline without careful stewardship. As ocean temperatures rise, acidification increases, and sea ice patterns shift, the future of these cold-adapted creatures remains uncertain. Protecting king crab populations requires continued commitment to science-based fishery management, habitat conservation, and meaningful action on climate change. The presence of these magnificent crustaceans scuttling across the seafloor serves as an indicator of ocean health—their continued survival depends on decisions we make today about how we value and protect the marine ecosystems they call home.

Scientific Name: Paralithodes camtschaticus (Red King Crab)

Diet Type: Omnivore

Size: Leg span up to 6 feet; carapace up to 11 inches

Weight: 10-24 pounds (exceptional individuals over 28 pounds)

Region Found: North Pacific Ocean, Bering Sea, coastal waters from Alaska to Russia, Japan, and Korea