Along the mudflats and mangrove forests of coastlines worldwide, a peculiar little creature performs what appears to be an endless beckoning gesture. The fiddler crab, with its comically oversized claw held aloft like a violinist’s bow, is one of the most charismatic residents of the intertidal zone. These diminutive crustaceans may measure no larger than a few centimeters across, yet they play an outsized role in coastal ecosystems, aerating sediment, recycling nutrients, and providing food for countless predators. But what makes fiddler crabs truly captivating is their remarkably complex social behavior—from their elaborate courtship dances to their fierce territorial disputes—all orchestrated by creatures with brains smaller than a grain of rice. In a world where we often overlook the small and seemingly simple, the fiddler crab stands as a testament to the incredible complexity that evolution can pack into the tiniest of packages.

Facts

- Male fiddler crabs possess one massively enlarged claw that can account for up to 65% of their total body weight, making them hilariously asymmetrical creatures.

- These crabs have exceptional color vision and can see polarized light, allowing them to detect predators and assess the quality of potential mates with remarkable precision.

- Fiddler crabs are among the few animals that can regenerate lost limbs, and intriguingly, if a male loses his large claw, it will regrow on the opposite side of his body during the next molt.

- They build elaborate burrows that can extend up to two feet deep, complete with multiple chambers and sophisticated ventilation systems that help regulate temperature and oxygen levels.

- Fiddler crabs have an internal biological clock so precise that they can anticipate tidal changes, emerging from their burrows at optimal feeding times even when kept in laboratory conditions far from the ocean.

- A single square meter of mudflat can contain over 100 fiddler crab burrows, making them one of the most densely populated invertebrates in coastal environments.

- Despite living in saltwater environments, fiddler crabs must carefully regulate their internal salt concentration and actually drink fresh water when available to maintain proper physiological balance.

Species

Kingdom: Animalia

Phylum: Arthropoda

Class: Malacostraca

Order: Decapoda

Family: Ocypodidae

Genus: Uca (recently reclassified under multiple genera including Gelasimus, Minuca, and Leptuca)

Species: Approximately 106 recognized species

The fiddler crab isn’t just one species but rather a diverse group of closely related crabs that have evolved to occupy similar ecological niches across the globe. Some of the most well-studied species include the Atlantic sand fiddler crab, which inhabits the eastern coast of North America from Massachusetts to Florida, and the red-jointed fiddler crab, found in similar regions but preferring muddier substrates. In the Indo-Pacific region, species like the calling fiddler crab dominate mangrove ecosystems, while the Gulf coast fiddler crab thrives in the warm waters of the Gulf of Mexico.

Recent genetic analysis has led to a reclassification of the genus Uca, splitting it into multiple genera based on evolutionary relationships. Despite their geographic separation, all fiddler crab species share the characteristic oversized claw in males and similar behavioral patterns, representing a remarkable example of convergent evolution in response to similar environmental pressures. Some species have adapted to extremely specific habitats, with certain variants found only in isolated mangrove systems or particular types of estuarine environments, making them excellent indicators of coastal ecosystem health.

Appearance

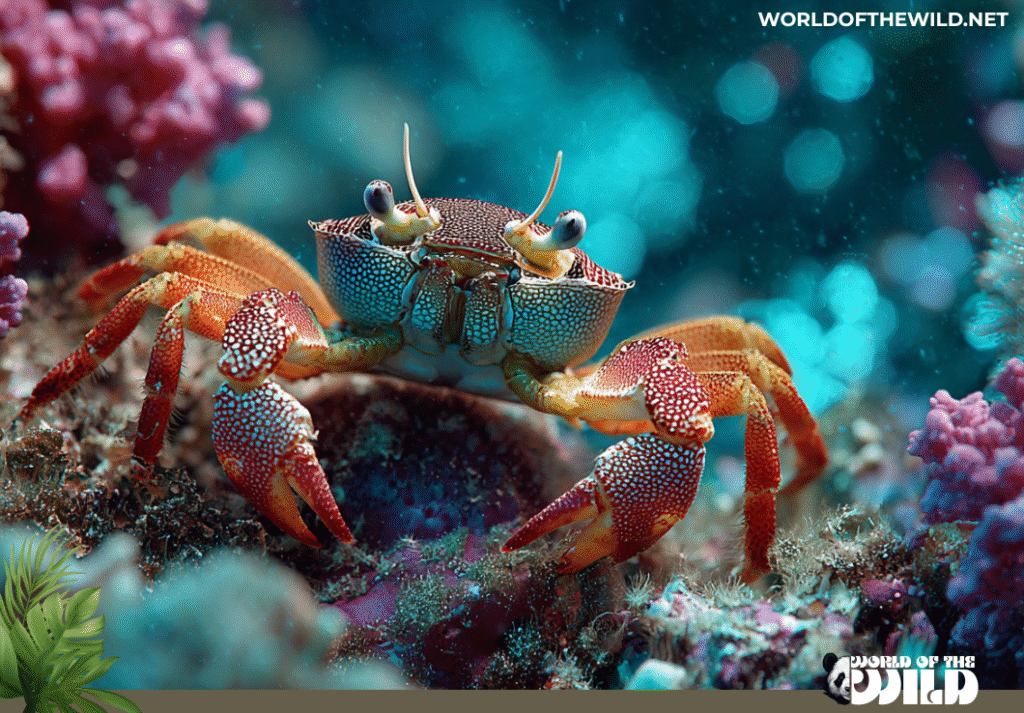

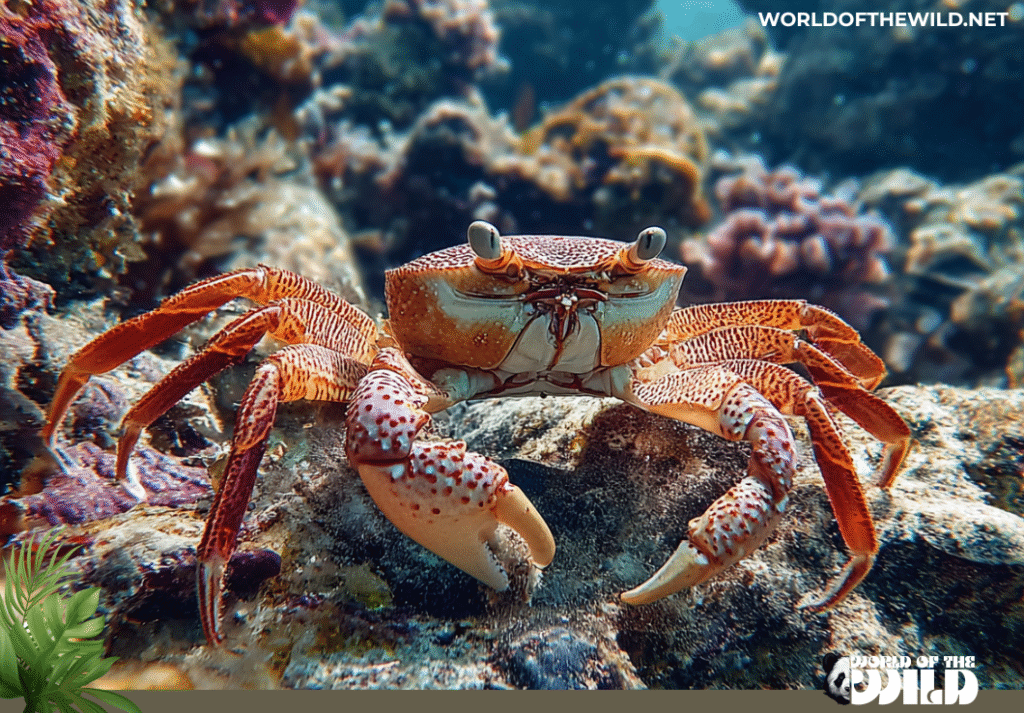

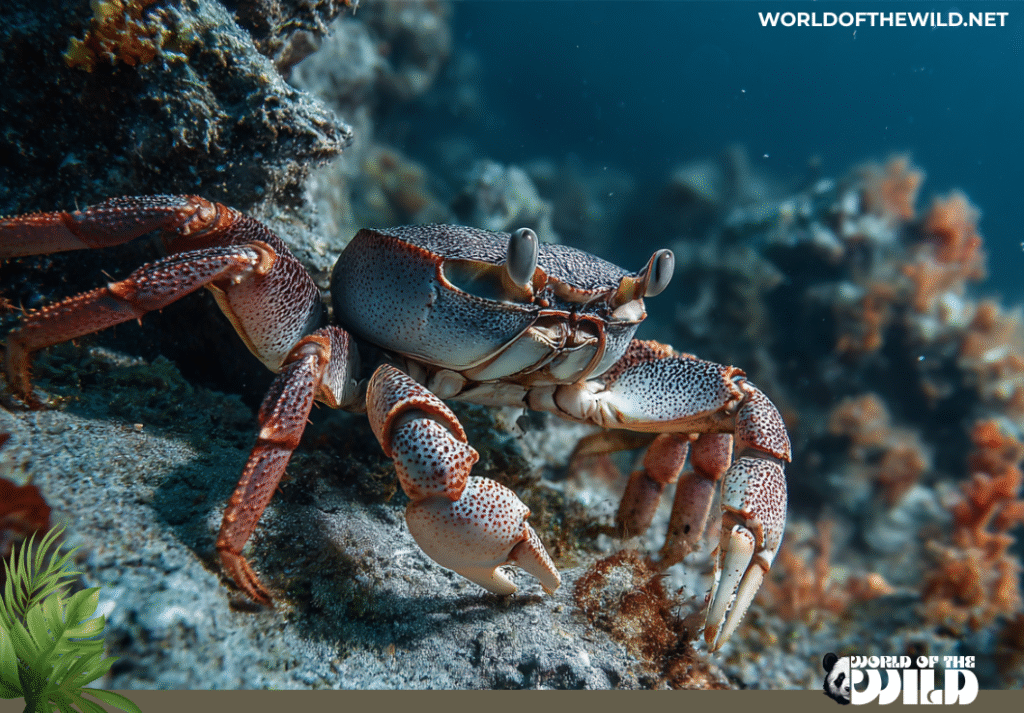

Fiddler crabs are small, compact crustaceans with bodies typically ranging from 1.5 to 3 centimeters in width, though some species can reach up to 5 centimeters. The most striking feature of male fiddler crabs is their dramatically enlarged major claw, which dwarfs the corresponding smaller minor claw on the opposite side. This massive appendage, held in a distinctive raised position that inspired their common name, can be brightly colored in shades of orange, red, pink, or white, contrasting sharply with their carapace. Female fiddler crabs, by contrast, possess two small, symmetrical claws of equal size, making sexual identification immediately apparent.

The carapace, or upper shell, displays a smooth, somewhat square or trapezoidal shape when viewed from above. Coloration varies dramatically between species and can include combinations of brown, gray, blue, purple, orange, and even vibrant reds, often with intricate patterns that help with species recognition and mate selection. Many species exhibit color polymorphism, with individuals in the same population displaying different color morphs. Their eyes are mounted on long, movable stalks that can retract into protective grooves on the carapace, giving them nearly 360-degree vision—crucial for spotting predators and rivals.

Eight walking legs, arranged in four pairs, give the fiddler crab its characteristic sideways scuttling motion. These legs are typically colored similarly to the carapace and are equipped with specialized setae (hair-like structures) that help detect vibrations in the substrate. The abdomen is tucked underneath the body, as with all true crabs, and is broader in females than males to accommodate egg masses during breeding season.

Behavior

Fiddler crabs are quintessentially social creatures, living in dense colonies that can number in the thousands. Their daily routine is dictated by the tides, with activity peaks occurring during low tide when mudflats are exposed. As the water recedes, hundreds of crabs emerge from their burrows in a coordinated exodus, transforming barren mud into a living carpet of scuttling crustaceans.

Males engage in one of nature’s most energetic displays: the claw-waving courtship ritual. Standing at the entrance to their burrows, they raise and lower their enormous claw in species-specific patterns—some wave vertically, others laterally, and still others perform complex circular motions. This semaphore-like signaling serves multiple purposes: attracting females, warning rival males, and advertising the quality of their burrow. The vigor and frequency of waving directly correlates with a male’s physical condition, making it an honest signal of fitness. During peak breeding season, males may wave thousands of times per day, an exhausting expenditure of energy that only the healthiest individuals can sustain.

Territoriality is intense among male fiddler crabs. Each defends a small territory centered on his burrow, engaging in ritualized combat with intruders. These battles typically begin with threatening displays, but can escalate to actual claw-to-claw wrestling matches where opponents attempt to flip each other over or force one another away from contested ground. Despite the potential for injury, most encounters end without serious harm, with the weaker individual retreating.

Communication extends beyond visual displays. Fiddler crabs produce substrate-borne vibrations by drumming their claws against the ground, creating signals that travel through the mud to nearby individuals. They also engage in chemical communication, detecting pheromones and other chemical cues that provide information about sex, reproductive status, and individual identity.

Their feeding behavior demonstrates remarkable efficiency. Using their minor claw (or both claws in females), they scoop sediment to their mouthparts, where specialized structures filter out organic particles, bacteria, algae, and detritus. The cleaned sediment is then deposited in small balls around their burrow entrance, creating distinctive feeding patterns that can be seen across the mudflat. This behavior makes them essential ecosystem engineers, processing and aerating vast quantities of sediment.

When threatened, fiddler crabs retreat rapidly to their burrows, often plugging the entrance with mud or their own body. They exhibit an impressive spatial memory, remembering the location of their burrow even when making foraging excursions several meters away, and can navigate back using visual landmarks and path integration.

Evolution

The evolutionary history of fiddler crabs stretches back approximately 23 million years to the early Miocene epoch, though their ancestors in the broader crab lineage extend much further into the Cretaceous period, over 100 million years ago. Fossil evidence of early fiddler crab species is rare due to their small size and preference for soft sediment environments that don’t preserve well, but burrow trace fossils and occasional preserved specimens have provided glimpses into their ancient past.

The development of the sexually dimorphic enlarged claw in males represents one of the most extreme examples of sexual selection in the animal kingdom. This trait evolved as females began preferring males with larger claws, creating a runaway selection process that resulted in the absurdly oversized appendages we see today. Interestingly, this evolution came with significant costs: the large claw is useless for feeding, makes males more conspicuous to predators, and requires enormous energy to grow and maintain. That such a handicapping trait persisted and intensified suggests extraordinarily strong sexual selection pressures.

Genetic studies have revealed that the diversification of fiddler crab species occurred in multiple waves of radiation, with different lineages colonizing suitable coastal habitats around the world. The Americas appear to be the center of fiddler crab diversity, suggesting this may have been their ancestral homeland. From there, various lineages dispersed to Africa, Asia, and the Indo-Pacific, adapting to local conditions and evolving into distinct species.

The transition from marine to semi-terrestrial life represents a key evolutionary innovation for fiddler crabs. Unlike their fully aquatic ancestors, modern fiddler crabs have evolved numerous adaptations for surviving in the challenging intertidal zone, including modified gills that function more efficiently in air, behavioral mechanisms for preventing desiccation, and sophisticated burrow-building behaviors. These adaptations allowed them to exploit the incredibly productive but harsh environment where land meets sea, avoiding competition with purely aquatic or terrestrial species.

Recent molecular clock analyses suggest that the major lineages of modern fiddler crabs diverged during periods of global climate change when sea levels fluctuated dramatically, creating and destroying coastal habitats and driving speciation through geographic isolation.

Habitat

Fiddler crabs are found on every continent except Antarctica and Europe, thriving along tropical, subtropical, and some temperate coastlines worldwide. In the Americas, they range from the eastern United States down through the Caribbean, Central America, and along both coasts of South America. African populations inhabit the western and eastern coasts, while Asian populations are particularly abundant throughout Southeast Asia, India, and coastal China. Australian and Pacific island populations round out their global distribution, making them one of the most geographically widespread groups of coastal invertebrates.

These crabs are quintessential residents of the intertidal zone, that narrow band where ocean meets land. They show strong preferences for soft substrates including mudflats, sandy beaches, salt marshes, and mangrove forests. The ideal fiddler crab habitat features a gentle slope that remains exposed during low tide for several hours daily, providing ample feeding time, yet is submerged during high tide, preventing desiccation and allowing them to replenish water and oxygen in their gill chambers.

Mangrove forests represent particularly important habitat for many species, as the complex root systems provide shelter, and the constant input of decaying organic matter creates rich feeding grounds. Salt marshes dominated by cordgrass and other halophytic plants offer similar benefits, with the additional advantage of softer sediment that makes burrow construction easier. Some species have adapted to living in the supratidal zone, venturing onto drier land and relying on moisture stored in their burrows rather than regular tidal inundation.

Salinity preferences vary by species, with some tolerating nearly freshwater conditions in river deltas, while others thrive only in full-strength seawater or even hypersaline lagoons. Temperature is another critical factor, with most species restricted to regions where water temperatures remain above 15°C year-round, though some temperate species can tolerate colder conditions by entering a state of reduced activity during winter months.

The quality of sediment is crucial—fiddler crabs prefer substrates with high organic content that provide adequate nutrition, but the sediment must also have the right consistency for burrow construction, neither too loose and sandy (which causes collapse) nor too dense and clayey (which makes digging difficult). They’re often found in areas where freshwater and saltwater mix, benefiting from nutrient inputs carried by rivers and streams.

Diet

Fiddler crabs are detritivores and omnivores, playing a critical role in coastal food webs as recyclers of organic matter. Their diet consists primarily of organic detritus—decomposing plant material, dead algae, bacteria, fungi, and the microscopic organisms that colonize decaying matter. When feeding, they use their small feeding claw (or both claws in females) to scoop sediment to their mouth, where specialized mouthparts called maxillipeds sort through the material, extracting nutritious particles and returning cleaned sediment to the surface.

The feeding process is remarkably selective. Fiddler crabs can distinguish between particles based on size, nutritional content, and digestibility, preferentially consuming items rich in protein and rejecting inorganic materials. They feed primarily on microalgae, including benthic diatoms that form films on mudflat surfaces, as well as bacteria and meiofauna—tiny organisms living between sediment grains. During certain seasons, when algal blooms occur or particular plants shed their leaves, fiddler crabs may show preferences for these temporarily abundant food sources.

Some species supplement their detritivorous diet with more active predation, capturing small invertebrates like nematode worms, or scavenging recently dead fish and other animals. They’ve also been observed feeding on the fecal matter of larger animals, extracting nutrients that passed through incompletely digested.

The feeding activity of fiddler crabs has profound effects on their environment. By processing sediment, they increase oxygen penetration into deeper layers, alter nutrient cycling, and affect the composition of microbial communities. A single crab can process several grams of sediment per day, and with population densities often exceeding 100 individuals per square meter, their collective impact on coastal biogeochemistry is substantial.

Male fiddler crabs face a unique feeding challenge due to their asymmetry. With only one small claw available for feeding compared to the female’s two, males can process sediment at only about half the rate of females. This feeding handicap, combined with the energy costs of maintaining and waving the large claw, means males must be significantly more efficient in selecting high-quality feeding sites or spend longer periods foraging.

Predators and Threats

Fiddler crabs occupy a crucial position in coastal food webs, serving as prey for a diverse array of predators both aquatic and terrestrial. Wading birds represent their most significant natural predators—herons, egrets, ibises, and various shorebirds time their foraging activities to coincide with low tides when crabs are most exposed. These birds have evolved specialized hunting techniques, with some species standing motionless and striking with lightning speed, while others actively stalk through colonies. Gulls and terns also consume fiddler crabs, particularly juveniles.

In the water, numerous fish species prey on fiddler crabs, including juvenile tarpon, snook, redfish, and various drum species. During high tide, these predators cruise over temporarily submerged mudflats, capturing crabs that venture from their burrows or fail to seal themselves in time. Blue crabs and other predatory crustaceans also hunt fiddler crabs, particularly during nighttime high tides.

Terrestrial predators include raccoons, which are skilled at excavating burrows and extracting the occupants, as well as various snake species, lizards, and even certain mammals like river otters. Ghost crabs, larger relatives of fiddler crabs, prey on smaller fiddler crab species, particularly juveniles and recently molted individuals with soft shells.

The most serious threats to fiddler crab populations, however, are anthropogenic. Coastal development represents the primary danger, with mangrove deforestation, wetland drainage, and shoreline hardening destroying habitat at alarming rates. The construction of seawalls, bulkheads, and other structures eliminates the gradual slope of natural intertidal zones that fiddler crabs require. Urban and agricultural runoff introduces pollutants including heavy metals, pesticides, and excess nutrients that can directly poison crabs or degrade their habitat through eutrophication and algal blooms.

Climate change poses multiple threats: sea-level rise may drown existing habitat faster than new habitat can form, while increased storm intensity destroys established populations. Rising temperatures can push some populations beyond their thermal tolerance limits, and ocean acidification may affect the ability of crabs to produce their calcium carbonate exoskeletons. Changes in precipitation patterns alter salinity regimes, potentially making habitats unsuitable for species with narrow salinity tolerances.

Plastic pollution is an emerging concern, as microplastics accumulate in sediments where fiddler crabs feed, potentially causing internal damage and transferring up the food chain. Some studies have also documented behavioral changes in crabs exposed to microplastics, including reduced burrowing activity and altered feeding patterns.

In some regions, fiddler crabs are harvested for use as fishing bait, and while small-scale collection may be sustainable, intensive harvesting can significantly impact local populations. Additionally, their use as bioindicators means declining populations often signal broader ecosystem degradation, serving as an early warning of coastal habitat deterioration.

Reproduction and Life Cycle

Fiddler crab reproduction is intricately tied to tidal and lunar cycles, with most species timing their breeding to coincide with spring tides—the highest tides that occur during new and full moons. The reproductive process begins with the elaborate courtship displays for which fiddler crabs are famous. Males construct and maintain burrows that serve not only as refuges from predators and desiccation but also as critical reproductive sites.

The claw-waving display is the male’s primary tool for attracting females. Each species has a distinctive waving pattern, ranging from simple vertical movements to complex figure-eight motions, performed at characteristic speeds and rhythms. Females wander through colonies of displaying males, apparently assessing both the quality of the visual display and the location and construction of the burrow. High-quality burrows—those that are properly positioned relative to the tide line, with appropriate depth and structure—are highly desirable, as they provide better protection for the female and her developing eggs.

Once a female selects a mate, she enters his burrow, and mating occurs underground. The male deposits sperm packets called spermatophores, which the female stores internally. She may mate with multiple males, storing sperm from each, and has some control over which male’s sperm fertilizes her eggs—a phenomenon known as cryptic female choice.

After mating, females develop a clutch of eggs that can number from several hundred to several thousand, depending on the species and the female’s size. These eggs are extruded and attached to specialized appendages called pleopods on the underside of the female’s abdomen, forming a spongy mass that gives gravid females a distinctive appearance. The female carries this egg mass for approximately two weeks, during which time she must carefully maintain optimal conditions, aerating the eggs by pumping her abdomen and protecting them from predators and parasites.

Egg release is timed with precision to nocturnal high tides, when females emerge from their burrows and perform distinctive pumping motions that release thousands of larvae into the water. This timing helps ensure that larvae are swept out to sea, away from the shallow waters where predators are abundant. The larvae are planktonic, drifting in ocean currents and developing through several distinct zoeal stages over the course of several weeks.

During their planktonic phase, larvae feed on microscopic phytoplankton and zooplankton, growing and molting through four to five zoeal stages before metamorphosing into megalopae—a transitional stage between larva and juvenile crab. Megalopae begin seeking suitable settlement habitat, using chemical and physical cues to locate appropriate mudflats or mangrove forests. Upon finding suitable substrate, they undergo a final metamorphosis into juvenile crabs.

Juvenile crabs face high mortality rates from predation and environmental stress. Those that survive grow through successive molts, gradually developing the characteristic features of adults. Males begin developing their asymmetry early, with one claw—determined randomly—growing larger with each molt. Sexual maturity is typically reached within one to two years, depending on the species and environmental conditions.

Adult fiddler crabs generally live for two to three years in the wild, though some individuals may survive longer under optimal conditions. Females can produce multiple clutches during a single breeding season, and across their lifetime may release millions of larvae, though only a tiny fraction will survive to adulthood. This high reproductive output compensates for the enormous mortality during the vulnerable larval and juvenile stages, ensuring population persistence despite intense predation pressure.

Population

The conservation status of fiddler crabs varies considerably across species, with most classified as Least Concern by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), though many species have not been formally assessed due to limited data. The widespread distribution and high reproductive output of most species have helped maintain stable populations despite localized threats. However, this general pattern masks concerning declines in specific regions and for particular species.

Estimating global fiddler crab populations is extraordinarily difficult due to their patchy distribution, cryptic behavior, and the logistical challenges of surveying intertidal habitats. However, local population density studies provide insight into their abundance: healthy mudflat populations can contain 100-200 individuals per square meter, and a single mangrove forest might support millions of individuals across multiple species. Extrapolating from suitable habitat availability, global populations likely number in the billions.

Population trends are highly variable geographically. In regions with intact coastal ecosystems and effective environmental protection, populations remain robust. However, areas experiencing rapid coastal development, particularly in Southeast Asia, Central America, and parts of Africa, have seen dramatic population declines. Some species with extremely limited ranges, particularly those endemic to small island systems or isolated estuaries, are vulnerable to local extinction from single catastrophic events like hurricanes or oil spills.

Certain species face more specific concerns. Those dependent on mangrove forests have declined in lockstep with mangrove deforestation, which has eliminated approximately 35% of global mangrove coverage over the past several decades. Species requiring specific salinity regimes are threatened by altered freshwater flow from dam construction and water diversion projects. In heavily polluted estuaries, fiddler crab populations have disappeared entirely, serving as indicators of severe ecosystem degradation.

Climate change presents an uncertain future for fiddler crabs. While some species may benefit from warming temperatures expanding their range poleward, others in tropical regions may face thermal stress. Sea-level rise could create new intertidal habitat in some areas while drowning existing habitat in others, and the net effect on global populations remains unclear.

Conservation efforts for fiddler crabs are generally indirect, focusing on protecting coastal habitats rather than the crabs specifically. Mangrove restoration projects, wetland preservation initiatives, and regulations limiting coastal development all benefit fiddler crab populations. Several countries have established protected areas encompassing important intertidal zones, and international agreements like the Ramsar Convention on Wetlands provide frameworks for conserving these ecosystems.

Monitoring programs that use fiddler crabs as bioindicators of coastal health have expanded in recent years, providing valuable data on population trends and environmental conditions. These programs recognize that healthy fiddler crab populations indicate healthy coastal ecosystems that provide numerous other services including fisheries support, storm protection, and carbon sequestration.

Conclusion

The fiddler crab, despite its diminutive size, emerges as a giant of coastal ecosystems—an ecological engineer whose burrowing aerates sediment, a food source supporting diverse predators, and a creature of remarkable behavioral complexity. From the male’s energy-intensive courtship displays to the species’ precise coordination with tidal rhythms, these crabs demonstrate that evolutionary sophistication is not the exclusive domain of large-brained vertebrates. Their global distribution across tropical and subtropical coastlines speaks to their ecological success, yet this very ubiquity makes their local declines particularly concerning.

As human development continues its relentless march into coastal zones, the mudflats and mangroves that fiddler crabs call home disappear beneath concrete and asphalt. When we lose these habitats, we lose more than charismatic little crabs with oversized claws—we lose the countless ecosystem services these environments provide, from nursery grounds for commercial fish species to natural storm barriers protecting human communities. The fiddler crab’s fate is inextricably linked to our own relationship with the coast. By protecting the intertidal zones where these crabs thrive, we protect ourselves and the extraordinary biodiversity that makes our planet resilient and beautiful. The next time you encounter a mudflat teeming with these waving crustaceans, recognize it not as wasteland but as a vital, functioning ecosystem worthy of our respect and protection.

Scientific Name: Uca spp. (now classified under genera including Gelasimus, Minuca, and Leptuca)

Diet Type: Detritivore/Omnivore

Size: 1.5-5 cm carapace width

Weight: 5-30 grams

Region Found: Tropical, subtropical, and temperate coastlines worldwide (excluding Antarctica and Europe)