Few animals command the human imagination quite like the lion. With its thunderous roar echoing across the savanna and its magnificent mane rippling in the golden light of an African sunset, this apex predator has captivated civilizations for millennia. From ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs to modern cinema, the lion has symbolized courage, royalty, and raw power. Yet beyond the mythology and symbolism lies an animal of extraordinary complexity—a social carnivore whose survival strategies, family dynamics, and evolutionary journey reveal nature’s remarkable creativity. Today, as these majestic cats face mounting pressures from habitat loss and human conflict, understanding the lion has never been more critical to ensuring its survival.

Facts

- Roar Power: A lion’s roar can reach 114 decibels and be heard up to 5 miles away, making it one of the loudest vocalizations in the animal kingdom—louder than a chainsaw or rock concert.

- Lazy Kings: Lions sleep or rest for approximately 20 hours per day, making them one of the most inactive large carnivores, conserving energy for brief but intense hunting sessions.

- Female Hunters: Lionesses do 85-90% of the hunting for their pride, working in coordinated teams while males primarily defend territory and protect cubs from rival males.

- Unique Manes: Each male lion’s mane is as distinctive as a fingerprint, with darker, fuller manes typically indicating better health, higher testosterone levels, and greater fighting ability—traits that attract females.

- Ancient Range: Just 10,000 years ago, lions had the largest range of any land mammal except humans, inhabiting Europe, Asia, Africa, and even North America (the related American lion).

- Infanticide Strategy: When new males take over a pride, they often kill existing cubs to bring females into estrus faster, ensuring their own genetic legacy—a brutal but effective evolutionary strategy.

- Water Independence: Unlike many large mammals, lions can survive in very arid environments and can go 4-5 days without drinking, obtaining much of their moisture from prey blood and body fluids.

Sounds of the Lion

Species

Classification:

- Kingdom: Animalia

- Phylum: Chordata

- Class: Mammalia

- Order: Carnivora

- Family: Felidae

- Genus: Panthera

- Species: Panthera leo

The lion belongs to the genus Panthera, which includes the tiger, leopard, jaguar, and snow leopard—the only cats capable of true roaring due to a specialized larynx structure. Historically, taxonomists recognized numerous lion subspecies based on geographic distribution and physical variations, but modern genetic studies have simplified this classification considerably.

Today, scientists recognize two primary subspecies:

African Lion (Panthera leo leo): This subspecies encompasses all lions in Central, West, and East Africa, as well as the critically endangered Asiatic lion population in India’s Gir Forest. Recent genetic research revealed that African and Asiatic lions are more closely related than previously thought, collapsing the traditional subspecies distinction.

Southern African Lion (Panthera leo melanochaita): Found in Southern and East Africa, this subspecies includes the famous lions of the Serengeti, Kruger, and Okavango Delta.

The extinct Barbary lion of North Africa, Cave lion of Ice Age Europe, and American lion represent distinct evolutionary lineages. Some taxonomists still debate finer distinctions between regional populations, but the two-subspecies model currently enjoys the strongest genetic support.

Appearance

Lions are the second-largest living cats after tigers, with an imposing physique built for power rather than speed. Males typically measure 5.6 to 8.2 feet in body length, with tails adding another 27 to 41 inches. They stand 3.5 to 4 feet tall at the shoulder and weigh between 330 to 550 pounds, though exceptional individuals can exceed 600 pounds. Females are considerably smaller, measuring 4.6 to 6 feet in length and weighing 265 to 395 pounds.

The most striking feature of adult males is their magnificent mane, a thick collar of hair that extends from the head down the neck and chest, sometimes continuing along the belly. Mane color varies from blonde to black, with darker manes generally indicating prime specimens. The mane serves multiple purposes: it makes males appear larger during confrontations, protects the neck during fights, and signals health and vitality to females. Interestingly, Tsavo lions in Kenya are famous for being nearly maneless, an adaptation possibly related to the region’s dense, thorny vegetation and hot climate.

Lions possess a tawny or sandy-colored coat that provides excellent camouflage in grassland environments. Their undersides are lighter, almost white, demonstrating countershading that helps them blend into their surroundings. Cubs are born with rosette spots that fade as they mature, remnants of their evolutionary heritage shared with leopards and jaguars.

The tail ends in a distinctive black tuft that conceals a claw-like spur in some individuals, the vestigial remnant of a tailbone extension. Their faces feature powerful jaws equipped with canine teeth reaching 3 inches in length, designed to deliver killing bites and hold struggling prey. Retractable claws on massive paws can extend to 1.5 inches, functioning as grappling hooks during hunts. Their eyes, adapted for nocturnal hunting, contain a reflective layer called the tapetum lucidum that amplifies available light, giving them vision six times better than humans in darkness.

Behavior

Lions are the only truly social cats, living in complex family groups called prides that typically consist of 3 to 6 related adult females, their cubs, and 1 to 3 adult males. This social structure represents a remarkable adaptation among felids, most of which are solitary. Pride size varies depending on prey availability and habitat, with some Serengeti prides exceeding 20 individuals.

Within the pride, females form the stable core, often remaining together for life. These related lionesses—mothers, daughters, sisters, and aunts—cooperate in hunting, cub-rearing, and territory defense. They exhibit remarkable coordination during hunts, with different individuals taking on specific roles: some become flankers, others act as centers, and a few serve as wings that encircle prey. This cooperative hunting allows lions to tackle prey much larger than themselves, including buffalo and young elephants.

Male lions live vastly different lives. Young males are expelled from their birth pride at 2-4 years of age and form nomadic coalitions with brothers or unrelated males. These coalitions roam between territories, seeking to overthrow resident males and claim a pride. Successful takeovers grant males breeding rights for typically 2-4 years before younger, stronger coalitions displace them. This system ensures genetic diversity while creating intense selective pressure favoring strength and cooperation among males.

Communication among lions is sophisticated and multifaceted. Their famous roar serves to advertise territorial ownership, coordinate pride members separated across vast distances, and intimidate rivals. Lions also employ a rich vocabulary of grunts, snarls, meows, and huffs. Tactile communication is equally important—lions frequently rub heads, groom each other, and rest in physical contact, behaviors that strengthen social bonds. Scent marking through urine, feces, and gland secretions helps delineate territory boundaries.

Lions demonstrate impressive intelligence, particularly in social learning and problem-solving. Cubs learn hunting techniques by watching their mothers, and individuals remember and recognize pride members after years of separation. Recent research reveals that lions can count the number of roaring intruders and adjust their defensive strategies accordingly, showcasing sophisticated cognitive abilities.

Evolution

The evolutionary story of lions reaches back approximately 1.9 million years to the Late Pliocene epoch in Africa. The lion’s lineage belongs to the Panthera group, which diverged from other big cats roughly 6.4 million years ago. The genus Panthera itself emerged from a common ancestor shared with leopards and jaguars, with molecular evidence suggesting lions split from this lineage around 1-2 million years ago.

The earliest definitive lion ancestor was Panthera leo fossilis, which appeared in Europe during the Early Pleistocene. This primitive lion gave rise to two main evolutionary branches: the Cave lion (Panthera spelaea) that dominated Ice Age Eurasia, and the lineage leading to modern African and Asiatic lions.

Cave lions were formidable creatures, slightly larger than today’s lions, with males possibly lacking full manes based on cave paintings by early humans. These magnificent predators ranged from Britain to Alaska, hunting megafauna like mammoths, woolly rhinoceros, and giant deer. Remarkably, frozen Cave lion cubs discovered in Siberian permafrost provide unprecedented insights into their appearance and biology. Cave lions went extinct approximately 14,000 years ago as Ice Age megafauna declined and human populations expanded.

Meanwhile, the African lineage flourished and expanded. During interglacial periods when sea levels dropped and land bridges emerged, lions dispersed into southern Europe and across the Middle East into India. The Asiatic lion population became isolated in the Gir Forest as human civilization expanded, while African populations remained widespread until recent centuries.

The American lion (Panthera atrox) represents a separate migration event, having crossed the Bering land bridge roughly 300,000 years ago. Though called a lion, genetic studies suggest it was more closely related to jaguars and may represent a distinct lineage. Standing 4 feet at the shoulder and weighing up to 800 pounds, American lions were the largest cats ever to exist in the Americas before their extinction around 11,000 years ago.

Lions’ evolutionary success stemmed from their unique adaptation to social living, which allowed them to exploit large prey resources in open habitats. This social structure, unprecedented among cats, gave lions a competitive advantage in grassland ecosystems where cooperation trumped solitary stealth.

Habitat

Historically, lions claimed the title of the most widespread large land carnivore after humans, ranging across Africa, southern Europe, the Middle East, and South Asia. Today, their range has contracted dramatically to less than 20% of their historical distribution. African lions now primarily inhabit sub-Saharan Africa, concentrated in fragmented populations across eastern and southern regions.

Lions prefer open woodlands, thick scrub, and grassland habitats where prey is abundant and visibility aids hunting. The iconic African savanna—characterized by golden grasses, scattered acacia trees, and seasonal rainfall—provides ideal conditions. These ecosystems offer the perfect balance: enough vegetation to provide stalking cover, sufficient openness to chase prey, and abundant herbivores to sustain large predators.

Major strongholds include Tanzania’s Serengeti-Mara ecosystem, Botswana’s Okavango Delta, Zimbabwe’s Hwange National Park, South Africa’s Kruger National Park, and Zambia’s South Luangwa. Each habitat presents unique challenges. In the Okavango Delta, lions have adapted to swimming between islands and hunting in wetlands, even taking hippopotamus and buffalo in water. In Namibia’s arid Skeleton Coast, desert-adapted lions survive in one of Earth’s harshest environments, covering enormous distances between scattered prey populations.

The Asiatic lion population is confined entirely to the Gir Forest National Park and surrounding areas in Gujarat, India, covering approximately 545 square miles. This dry deciduous forest, punctuated by grasslands and scrub, represents the species’ last Asian stronghold. Unlike their African cousins who live in vast, unfenced ecosystems, Gir’s lions coexist with human settlements, livestock, and agricultural lands in remarkably close proximity.

Lions require substantial territories, with pride territories ranging from 8 to 150 square miles depending on prey density. They are territorial animals that fiercely defend their ranges through scent marking, vocalizations, and, when necessary, violent confrontations.

Diet

Lions are obligate carnivores, requiring a diet consisting entirely of meat to survive. As apex predators, they sit at the top of the food chain, shaping ecosystem dynamics through their hunting behavior. An adult lion needs approximately 11 to 15 pounds of meat daily, though they can consume up to 70 pounds in a single feeding after a successful hunt, then go several days without eating.

Their prey selection varies by region and season but generally includes medium to large ungulates. Primary prey species include wildebeest, zebra, buffalo, gemsbok, giraffe, warthog, and various antelope species like impala, kudu, and topi. Lions demonstrate remarkable versatility, occasionally hunting elephants (particularly juveniles), hippopotamus, and even crocodiles. In some regions, they’ve been documented killing and eating ostrich, porcupines, and during desperate times, smaller animals like hares or birds.

Hunting strategies vary between males and females and depend on environmental conditions. Lionesses typically hunt cooperatively, employing sophisticated tactics that involve surrounding prey, with some individuals driving animals toward ambush positions where others wait. They prefer hunting during darkness when their superior night vision provides maximum advantage, though they also hunt during twilight hours and occasionally in daylight.

The kill itself is a brutal but efficient process. Lions typically target prey’s throat or muzzle, clamping powerful jaws to suffocate the victim—a method that minimizes the lion’s exposure to dangerous horns or hooves. For smaller prey, a bite to the neck severs the spinal cord instantly. Success rates hover around 25-30% for hunts, meaning lions face frequent failure and must hunt regularly.

Male lions have garnered reputations as lazy freeloaders, but this oversimplifies their role. While males do scavenge from female kills, they also hunt independently, particularly targeting large, dangerous prey like buffalo where their superior size and strength prove advantageous. Males are also more likely to drive off other predators from kills, essentially defending food resources for the pride.

Lions are opportunistic scavengers, readily appropriating kills from hyenas, leopards, and cheetahs. Contrary to popular belief, lions likely scavenge less than hyenas do, with studies suggesting they obtain 50% or less of their food through scavenging depending on prey availability.

Predators and Threats

As apex predators, adult lions face virtually no natural predators. However, cubs and young lions are vulnerable to multiple threats. Hyenas pose the most significant natural danger to lion cubs, killing them when adults are absent. Leopards occasionally kill unattended cubs, and African wild dogs may attack vulnerable youngsters. Large male lions represent the greatest threat to cubs through infanticide, killing offspring sired by previous males when taking over a pride.

Crocodiles can threaten lions at water sources, particularly in regions like the Okavango Delta where lions hunt in aquatic environments. Buffalo, elephants, and hippopotamus—all dangerous prey species—occasionally injure or kill lions during hunts, particularly when wounded animals fight back or protective mothers defend their young.

Human-caused threats dwarf natural dangers and represent the primary challenge to lion survival. Habitat loss stands as the most pervasive threat, with human agriculture, settlements, and infrastructure fragmenting and reducing lion ranges. Africa has lost approximately 75% of its wilderness areas, directly impacting lion populations that require vast territories.

Human-wildlife conflict exacts a devastating toll. Lions that prey on livestock face retaliatory killings by farmers and pastoralists protecting their livelihoods. In many regions, this conflict represents the leading cause of lion mortality. Poisoned carcasses—intended to kill predators—don’t discriminate between livestock-killers and innocent individuals, sometimes eliminating entire prides.

Trophy hunting remains controversial, with well-managed programs claimed to fund conservation in some countries while critics argue it removes prime breeding individuals and disrupts social structures. The death of Cecil the lion in Zimbabwe’s Hwange National Park in 2015 brought international attention to trophy hunting ethics and sparked global debate.

Illegal wildlife trade, while less significant for lions than for rhinos or elephants, still threatens populations. Lion bones are increasingly targeted for Asian traditional medicine markets as tiger populations decline, creating new poaching pressures. Live capture for captive facilities, particularly in Asia, has raised ethical and conservation concerns.

Prey base depletion through overhunting by humans reduces available food, forcing lions into closer contact with livestock and increasing conflict. Disease outbreaks, including canine distemper and bovine tuberculosis transmitted from domestic animals, have caused significant lion mortality in several populations.

Reproduction and Life Cycle

Lions exhibit a polygynous mating system where dominant males breed with multiple females within their pride. Unlike many mammals with distinct breeding seasons, lions can mate year-round, though births often peak following seasonal rains when prey abundance increases.

When a female enters estrus—a period lasting 4 days that recurs every 2-3 weeks until conception—she and her chosen male separate from the pride for an intense mating period. The pair may copulate 20 to 40 times per day over several days, a frequency that ensures successful fertilization and stimulates ovulation in the female. Mating is brief but vigorous, lasting only 20-30 seconds but repeated at remarkably short intervals.

The gestation period lasts approximately 110 days (roughly 3.5 months). As birth approaches, pregnant females leave the pride to find a secluded den—often in dense vegetation, caves, or rocky outcrops. Litter sizes typically range from 2 to 4 cubs, though females can give birth to up to 6. Cubs arrive blind and helpless, weighing just 2 to 4 pounds with spotted coats that provide camouflage.

For the first 6-8 weeks, mothers keep cubs hidden, visiting periodically to nurse. This isolation protects vulnerable newborns from infanticide by rival males and predation by hyenas. After two months, mothers introduce cubs to the pride, and communal rearing begins—one of the most remarkable aspects of lion society. Females within a pride often synchronize births and nurse each other’s cubs indiscriminately, strengthening social bonds and increasing cub survival through cooperative protection.

Cubs are weaned at 6-7 months but remain dependent on their mothers for food until 16 months. They begin accompanying adults on hunts at about 11 months, initially as observers before gradually participating. Play fighting between cubs and young adults serves crucial developmental purposes, teaching hunting tactics, establishing social hierarchies, and building physical strength.

Sexual maturity arrives at approximately 3-4 years for females and 5 years for males, though males typically don’t secure breeding rights until they’re strong enough to overthrow resident pride males, usually around 6-7 years. Females generally remain in their birth pride for life, while males are expelled at 2-4 years to prevent inbreeding.

In the wild, lions live 10-14 years on average, with females typically outliving males. Few wild males survive beyond 10 years due to the physical demands of territorial battles and solitary nomadic existence after losing their pride. Captive lions can live 20-25 years with veterinary care and guaranteed food. The harsh reality is that 60-70% of cubs die before reaching two years of age, succumbing to starvation, infanticide, predation, or disease.

Population

The lion’s conservation status tells a sobering story of decline. The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) classifies the African lion as “Vulnerable” on the Red List, while the Asiatic lion subspecies is listed as “Endangered.” These designations indicate populations facing high risk of extinction without intervention.

Current population estimates suggest approximately 20,000 to 25,000 lions remain in the wild across Africa, though numbers vary among surveys and methodologies make precision difficult. This represents a catastrophic decline from an estimated 200,000 lions a century ago—a 90% reduction. West African lions number fewer than 500 individuals scattered across fragmented populations and face an extremely uncertain future. Central African populations are similarly precarious, with fewer than 2,500 individuals.

The Asiatic lion population presents a paradoxical conservation story. Reduced to approximately 20 individuals in the 1890s, intensive protection efforts have increased the population to around 670-700 lions as of recent surveys. While this represents remarkable recovery, the entire population’s confinement to a single location creates catastrophic vulnerability to disease outbreaks or natural disasters that could eliminate the species in India.

Population trends vary regionally. Southern African countries with well-funded national parks and wildlife management programs have maintained relatively stable or even growing populations. Botswana, South Africa, Namibia, and Zimbabwe collectively host the largest lion populations with the most secure futures. Conversely, West and Central African populations continue declining precipitously due to inadequate protection, insufficient funding, and intensifying human pressures.

Key populations in Tanzania’s Serengeti-Mara ecosystem (approximately 3,000 lions), Botswana’s Okavango Delta (roughly 1,500 lions), and South Africa’s Kruger National Park (around 1,600 lions) serve as critical reservoirs for the species’ genetic diversity and long-term survival. However, many of these populations are increasingly isolated, leading to genetic bottlenecks and reduced adaptability.

Conservation initiatives offer hope. Trans-boundary conservation areas connecting parks across national borders help maintain genetic diversity through lion movement. Community-based conservation programs addressing human-wildlife conflict have reduced retaliatory killings in some regions. Compensation schemes for livestock losses, improved livestock management, and education programs show promise where properly implemented and funded.

Conclusion

The lion stands at a crossroads between its legendary past and uncertain future. This magnificent apex predator—whose roar once echoed across three continents, whose social complexity rivals our own, and whose ecological importance extends far beyond its role as hunter—now depends on human decisions for survival. The precipitous population decline, habitat fragmentation, and mounting human pressures paint a concerning picture, yet regional success stories demonstrate that conservation can work when adequately supported.

Lions serve as umbrella species whose protection benefits entire ecosystems. Their preservation requires addressing interconnected challenges: securing vast protected areas, reducing human-wildlife conflict through innovative programs, maintaining prey populations, and fostering coexistence between lions and the rapidly growing human populations sharing their landscape. The next few decades will likely determine whether wild lion populations persist outside of fenced reserves or whether these iconic cats become ecological refugees confined to isolated sanctuaries.

The lion’s fate ultimately reflects humanity’s willingness to share the planet with wildness itself. Supporting conservation organizations, promoting sustainable tourism that funds wildlife protection, and recognizing the intrinsic value of apex predators beyond their economic or symbolic worth can help ensure that future generations experience the awe of hearing a lion’s roar under African stars. The king of beasts has reigned for millennia—whether its kingdom endures depends on the choices we make today.

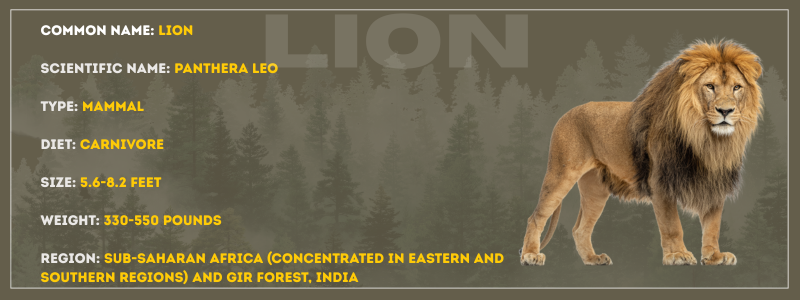

Scientific Name: Panthera leo

Diet Type: Carnivore

Size: Males: 5.6-8.2 feet (body length); Females: 4.6-6 feet (body length)

Weight: Males: 330-550 pounds; Females: 265-395 pounds

Region Found: Sub-Saharan Africa (concentrated in eastern and southern regions) and Gir Forest, India

Hungry for More? The hunt doesn’t end here. Dive into our complete collection of Big Cat guides and articles.