In the twilight hours when most creatures seek shelter, a formidable hunter emerges from the shadows. With piercing yellow eyes that can spot a mouse from 100 yards away and talons powerful enough to crush bone, the Great Horned Owl reigns as one of North America’s most magnificent apex predators. Often called the “tiger of the sky,” this remarkable bird commands respect from nearly every creature in its domain—and for good reason. The Great Horned Owl represents a stunning example of evolutionary perfection, combining stealth, power, and adaptability in ways that have allowed it to thrive across an enormous range of habitats. Whether you’ve heard its deep, resonant hooting echoing through a forest at dusk or glimpsed its silhouette perched majestically against a moonlit sky, encountering a Great Horned Owl is an experience that captures the wild mystery of the natural world.

Facts

- Silent but Deadly: The Great Horned Owl can fly in complete silence thanks to specialized feather structures that break up turbulence and muffle sound, allowing it to surprise prey with virtually no warning.

- Crushing Grip: Their talons exert approximately 500 pounds per square inch of pressure—roughly equivalent to the bite force of a large dog—making them capable of killing prey much larger than themselves.

- Fixed Eyes, Flexible Neck: Unable to move their eyes in their sockets, Great Horned Owls compensate with an incredible ability to rotate their heads up to 270 degrees in either direction without damaging blood vessels or cutting off circulation to the brain.

- Skunk Specialists: Unlike most predators, Great Horned Owls have a poorly developed sense of smell, which makes them one of the few animals willing and able to regularly hunt skunks without being deterred by their notorious spray.

- Long-Lived Raptors: In the wild, Great Horned Owls can live 13-15 years, but in captivity, they’ve been known to reach the impressive age of 28 years or more.

- Early Nesters: These owls are among the earliest breeding birds in North America, often laying eggs in January or February when snow still blankets the ground, giving their chicks a head start on the growing season.

- Fearless Defenders: Great Horned Owls are notoriously aggressive when defending their nests and have been known to attack humans, dogs, and even other large predators that venture too close to their young.

Sounds of the Great Horned Owl

Species

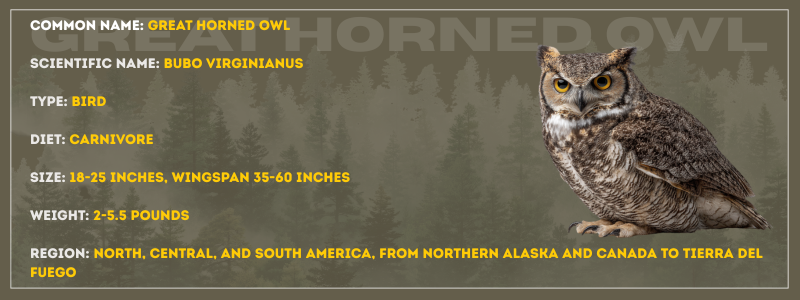

The Great Horned Owl belongs to the following taxonomic classification:

- Kingdom: Animalia

- Phylum: Chordata

- Class: Aves

- Order: Strigiformes

- Family: Strigidae

- Genus: Bubo

- Species: Bubo virginianus

The genus Bubo includes several other impressive owl species found around the world, including the Eurasian Eagle-Owl, the largest owl species. Within Bubo virginianus itself, scientists recognize between 10 and 20 subspecies distributed across the Americas, though the exact number remains debated among ornithologists. These subspecies show variations in size, coloration, and vocalizations based on their geographic locations. Some notable subspecies include B. v. virginianus of eastern North America, B. v. occidentalis of the western regions, B. v. subarcticus of the subarctic zones, and B. v. mayensis found in Central America. The variations among subspecies generally follow ecogeographical rules, with birds in colder climates tending to be larger and paler, while those in warmer, more humid regions are typically smaller and darker.

Appearance

The Great Horned Owl is an imposing bird, standing 18 to 25 inches tall with a wingspan that can reach an impressive 35 to 60 inches—nearly five feet from tip to tip. Adults typically weigh between 2 and 5.5 pounds, with females being noticeably larger and heavier than males, a characteristic common among birds of prey. Despite their substantial size, their actual body is relatively compact; much of their apparent bulk comes from their dense, fluffy plumage.

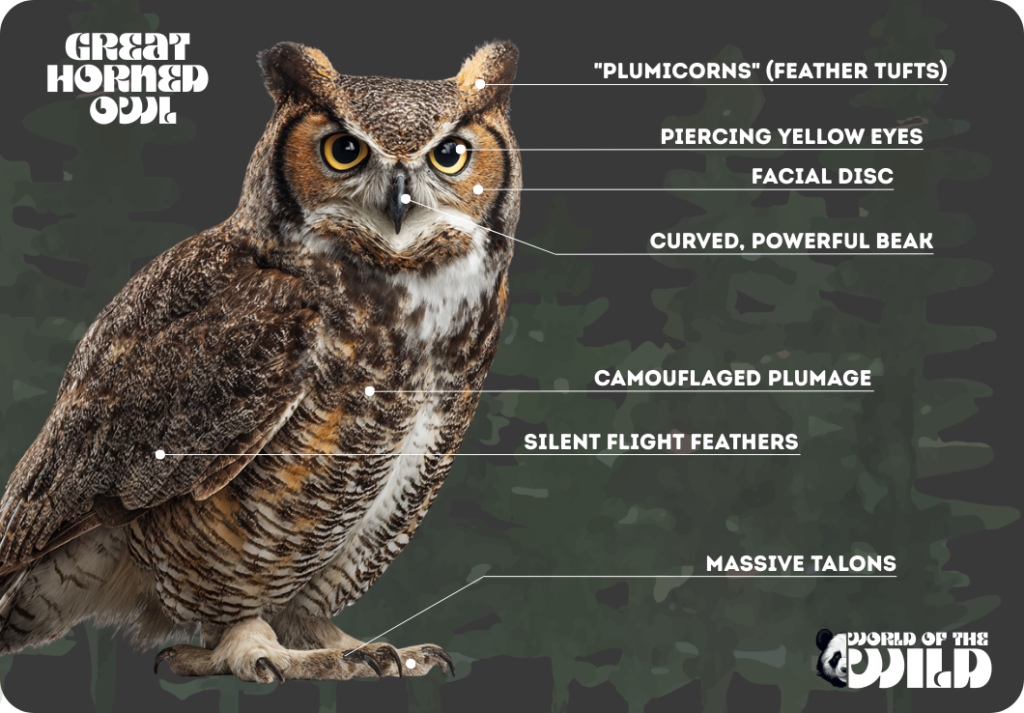

The most distinctive feature, and the source of their common name, is the pair of prominent feather tufts on their heads that resemble horns or ears. These “plumicorns” are not actually ears or horns but simply tufts of feathers whose exact purpose remains somewhat mysterious, though they may play a role in communication, camouflage, or species recognition. The owl’s actual ears are hidden beneath feathers on the sides of its head and are asymmetrically positioned to enhance their ability to pinpoint sounds in three-dimensional space.

Their plumage displays a complex mottled pattern of browns, grays, blacks, and whites that provides excellent camouflage against tree bark. The overall coloration varies considerably among individuals and subspecies, ranging from very dark, almost blackish birds in humid forests to pale, grayish birds in arid regions. A distinctive white throat patch, often called a “bib,” contrasts sharply with the darker plumage and becomes especially visible when the owl is vocalizing. The facial disc—the circular arrangement of feathers around the face—is rusty or reddish-brown, bordered by black, and helps funnel sound to the owl’s ears.

Perhaps their most arresting feature is their eyes: large, forward-facing, and a brilliant yellow or golden-amber color. These eyes are actually tubular in shape rather than spherical, which maximizes their light-gathering ability but prevents them from rotating in their sockets. The intense, unblinking stare of a Great Horned Owl has captivated humans for millennia and contributes to the bird’s reputation as a symbol of wisdom and mystery.

Their feet are heavily feathered all the way to their talons, providing insulation and protection. The talons themselves are black, sharply curved, and formidable weapons that never stop growing throughout the owl’s life, though they’re constantly worn down through use.

Behavior

Great Horned Owls are primarily nocturnal and crepuscular hunters, meaning they’re most active during the twilight hours of dawn and dusk and throughout the night. During daylight hours, they typically roost in secluded locations such as dense tree foliage, natural tree cavities, or abandoned buildings, where their cryptic coloration renders them nearly invisible. When discovered by other birds during the day, they often become the target of “mobbing” behavior, where groups of crows, jays, and other birds harass them with loud calls and dive-bombing attacks.

These owls are generally solitary outside of the breeding season, though mated pairs maintain territories year-round. They are highly territorial birds, and a breeding pair will vigorously defend their hunting grounds, which can range from one to several square miles depending on prey availability. Territory boundaries are established and maintained primarily through vocalization—their distinctive “hoo-hoo-hoo, hoo-hoo” call can carry for several miles and serves as both a declaration of ownership and a means of communication with mates.

Great Horned Owls are sit-and-wait predators, typically hunting from a perch where they can scan their surroundings with their exceptional vision and hearing. When prey is detected, the owl swoops down in silent flight, extending its talons forward at the last moment to strike with tremendous force. Their hunting success rate is remarkably high, partly due to their stealth and partly due to their opportunistic nature—they’ll hunt almost anything they can overpower.

Communication among Great Horned Owls involves a variety of vocalizations beyond their famous hooting. They produce barks, screams, and hisses, particularly when threatened or disturbed. Juveniles make distinctive begging calls that sound like raspy screeches or whistles. Body language also plays a role in communication, with threat displays involving fluffing feathers to appear larger, spreading wings, and snapping the bill to produce sharp clicking sounds.

Despite their fierce reputation, these owls display remarkable intelligence and problem-solving abilities. They’ve been observed learning to avoid certain prey items that fight back effectively, remembering productive hunting locations, and even adjusting their hunting strategies based on experience. In captivity, Great Horned Owls have demonstrated the ability to recognize individual humans and remember negative experiences for years.

Evolution

The evolutionary history of owls stretches back approximately 60 million years to the early Paleocene epoch, shortly after the extinction of the non-avian dinosaurs. The oldest known owl fossils, such as Ogygoptynx and Eostrix, show that even these ancient species possessed characteristics similar to modern owls, including forward-facing eyes and likely nocturnal habits. This suggests that the basic owl body plan proved successful early on and has been refined rather than dramatically altered over millions of years.

The Great Horned Owl’s genus, Bubo, is believed to have originated in the Old World, with fossil evidence of eagle-owl species dating back to the Miocene epoch, roughly 15-20 million years ago. The Great Horned Owl itself is thought to have evolved in North America during the Pleistocene, perhaps 2-3 million years ago, making it a relatively recent species in evolutionary terms.

During the Pleistocene ice ages, as glaciers advanced and retreated across North America, populations of Great Horned Owls became isolated in different refugia, which likely led to the development of the various subspecies we see today. When the ice retreated, these populations expanded and their ranges overlapped, but they maintained sufficient differences to be recognizable as distinct subspecies.

The Great Horned Owl’s success can be attributed to several key evolutionary adaptations. Their silent flight evolved through specialized feather structures, including a serrated leading edge on the primary flight feathers and a velvety texture on the feather surfaces. Their exceptional hearing developed through asymmetrical ear placement and a facial disc that acts as a parabolic reflector, channeling sound to the ears. Their powerful feet and talons evolved to be remarkably strong for their body size, allowing them to take prey much larger than most other owls would attempt.

Interestingly, the Great Horned Owl shows evolutionary convergence with the Eurasian Eagle-Owl, its Old World counterpart. Despite evolving on separate continents, both species developed similar sizes, hunting strategies, and ecological roles as apex avian predators in their respective ranges, demonstrating how similar environmental pressures can shape species in comparable ways.

Habitat

The Great Horned Owl boasts one of the most extensive ranges of any North American bird, inhabiting territory from the Arctic treeline in northern Alaska and Canada all the way south through Central America and into South America as far as Tierra del Fuego at the southern tip of Argentina. This enormous distribution spans from sea level to elevations exceeding 14,000 feet in mountainous regions. Very few other bird species can claim such a vast and varied range.

What makes the Great Horned Owl truly remarkable is its habitat versatility. These adaptable birds thrive in virtually every terrestrial habitat type within their range except for true Arctic tundra and the most barren deserts. They inhabit temperate deciduous and coniferous forests, tropical rainforests, boreal taiga, grasslands, agricultural areas, desert oases, mangrove swamps, and even suburban and urban parks. From the saguaro deserts of Arizona to the swampy bayous of Louisiana, from the rocky mountains of Colorado to the prairies of Kansas, Great Horned Owls have made themselves at home.

Despite this remarkable adaptability, Great Horned Owls do have certain habitat requirements. They need some form of elevated perching and nesting sites, whether trees, cliffs, or man-made structures. They also require a mix of open hunting grounds and perching cover—pure grassland or dense unbroken forest is less ideal than a mosaic of different habitat types. Areas with some mature trees interspersed with open spaces provide optimal conditions.

Within their territories, Great Horned Owls utilize specific features for different activities. Large, sturdy trees or cliffs serve as nesting sites, dense foliage provides daytime roosting cover, and edges between different habitat types create productive hunting zones. They show a particular affinity for riparian corridors—areas along rivers and streams—which concentrate prey species and provide diverse hunting opportunities.

Their habitat selection often brings them into close proximity with humans. They’ve readily adapted to fragmented landscapes and human-modified environments, frequently nesting in city parks, golf courses, farmland woodlots, and suburban neighborhoods. However, they still avoid areas of intense human activity, preferring locations that offer some degree of seclusion, particularly during nesting season.

Diet

The Great Horned Owl is a formidable carnivore with one of the most varied diets of any North American raptor. Their motto might well be “if it moves, it’s on the menu,” as these opportunistic predators have been documented consuming over 250 different prey species. This dietary flexibility is one of the keys to their success across such a wide range of habitats.

Mammals comprise the bulk of their diet in most regions, with rabbits and hares being particular favorites. A single rabbit can provide several meals for an owl, and populations of Great Horned Owls often fluctuate in response to cyclic rabbit populations. Other common mammalian prey includes rats, mice, voles, ground squirrels, muskrats, and even domestic cats. They’re capable of taking surprisingly large prey—there are documented cases of Great Horned Owls successfully hunting raccoons, opossums, porcupines, and young foxes.

Birds form the second major component of their diet, and here too, their prey selection is impressively diverse. They hunt everything from small songbirds to medium-sized waterfowl, including ducks, coots, and grouse. Remarkably, Great Horned Owls are one of the few predators that regularly prey upon other raptors, including smaller owl species, hawks, and even the occasional falcon or eagle chick. This habit of eating other birds of prey has earned them a complicated reputation among birders and wildlife rehabilitators.

In certain habitats, Great Horned Owls also consume significant numbers of reptiles and amphibians, including snakes, lizards, turtles, frogs, and toads. In coastal areas, they may eat crabs and fish. Insects, particularly large species like beetles and grasshoppers, may be consumed by juvenile owls or during times when other prey is scarce, though they don’t provide much nutritional value for such a large bird.

Their hunting strategy typically involves perch-and-pounce tactics. The owl sits motionless on a strategic perch, using its exceptional vision and hearing to detect prey, then swoops down to strike. The attack is usually swift and decisive—the owl’s talons hit with enough force to stun or kill prey instantly. For smaller prey, they may swallow it whole; larger prey is carried to a feeding perch where the owl tears it apart with its sharp, hooked beak. Like all owls, Great Horned Owls cannot digest fur, bones, teeth, feathers, and other hard parts, so they regurgitate these materials as compact pellets, typically 3-4 inches long, which accumulate beneath favorite roosting sites.

Predators and Threats

Adult Great Horned Owls sit near the top of the food chain and have few natural predators. Their large size, aggressive temperament, and powerful talons deter most would-be attackers. However, they’re not entirely invulnerable. Other large raptors, particularly Golden Eagles and occasionally Bald Eagles, may kill adult Great Horned Owls, especially when competing for territory or prey. In rare instances, large terrestrial predators like mountain lions, bobcats, or wolves might catch an owl on the ground or at a kill site, though such events are uncommon.

Eggs and young owlets face more numerous threats. Raccoons, large snakes, and corvids like crows and ravens will raid nests if given the opportunity, consuming eggs or small chicks. Other large owl species, particularly Barred Owls and other Great Horned Owls competing for territory, may kill young owlets. However, parental defense is typically fierce enough to drive off most nest predators, and the early nesting season means young owls grow quickly before other predators’ breeding seasons reach full swing.

The more significant threats to Great Horned Owls come from human activities. Vehicle collisions are a leading cause of death, as owls hunting along roadsides frequently fly low across highways in pursuit of prey and get struck by cars. These collisions peak during the breeding season when owls are most active and when young, inexperienced birds are dispersing to establish their own territories.

Electrocution from power lines and collisions with power lines and other structures kill substantial numbers of owls annually. Their large wingspan makes them particularly vulnerable to touching two wires simultaneously, completing a deadly circuit. Similarly, barbed wire fences can cause severe injuries to owls landing or taking off.

Secondary poisoning from rodenticides represents an insidious and growing threat. When owls consume rodents that have eaten poison bait, the toxins accumulate in the owl’s system, causing internal bleeding, neurological damage, or death. This is particularly problematic because a single poisoned rodent may not kill an owl, but the cumulative effect of consuming multiple contaminated prey animals can prove fatal. Anticoagulant rodenticides are especially dangerous and have been found in high percentages of Great Horned Owls submitted to wildlife rehabilitation centers.

Habitat loss and fragmentation impact Great Horned Owls less severely than more specialized species, thanks to their adaptability, but intensive development that eliminates all suitable nesting trees or hunting habitat can render areas unsuitable. Agricultural intensification that eliminates hedgerows, woodlots, and field edges reduces habitat quality.

Illegal shooting, though less common than in previous decades, still occurs. Some people mistakenly view Great Horned Owls as threats to poultry or game birds and kill them despite their protection under the Migratory Bird Treaty Act and similar legislation. Others shoot them for trophies or out of simple malice.

Climate change presents complex and less predictable threats. Shifting prey populations, changes in plant communities that affect habitat structure, and alterations to weather patterns during the critical winter breeding season could all impact owl populations in ways that are difficult to predict or quantify at present.

Reproduction and Life Cycle

Great Horned Owls are among the earliest breeding birds in North America, with courtship beginning as early as October or November. The male initiates courtship with increasingly frequent hooting, which intensifies as winter progresses. Mated pairs engage in duetting, with the female’s voice noticeably deeper and hoarser than the male’s. These vocal performances strengthen pair bonds and advertise territory ownership to potential competitors.

Courtship displays include bowing, mutual preening, and the male presenting food gifts to the female. Great Horned Owls typically mate for life, though they will seek new partners if one dies. Established pairs often return to the same general nesting area year after year, though they may use different specific nest sites.

Great Horned Owls don’t build their own nests. Instead, they’re nest pirates, appropriating structures built by other species. Red-tailed Hawk nests are particular favorites, but they’ll also use nests built by other large hawks, herons, crows, or ravens. Alternatively, they may nest in natural tree cavities, cliff ledges, caves, or even on the ground in treeless habitats. In urban areas, they sometimes nest on building ledges or in other man-made structures. The female may add minimal material to the nest—perhaps some bark chips or feathers—but renovation is usually minimal.

Egg-laying occurs remarkably early, typically between late January and early March in most of their range, though timing varies by latitude and local climate. The female lays a clutch of one to five eggs (usually two or three), which are round, dull white, and roughly the size of a chicken egg. She begins incubating immediately after laying the first egg, which means the eggs hatch asynchronously, with several days between siblings.

Incubation lasts approximately 30-37 days and is performed almost entirely by the female, while the male provides food. During this period, the female rarely leaves the nest, even during severe winter storms. This early nesting schedule means owlets are often developing in harsh winter conditions, but it gives them a competitive advantage, allowing them to grow large before the spring breeding rush of other species.

The newly hatched owlets are covered in white down and are completely helpless, their eyes closed for the first week. The female broods them continuously for the first two weeks while the male hunts intensively to feed the growing family. Both parents become extremely aggressive during this period, attacking any potential threat—human, animal, or otherwise—that approaches the nest.

As the owlets grow, they develop a second, denser coat of grayish down. By six to seven weeks of age, they begin branching—leaving the nest to hop and climb among nearby branches, though they cannot yet fly. This can be a dangerous period, as young owls sometimes fall to the ground. Despite not being able to fly, these branchers are not abandoned; the parents continue feeding and protecting them. By nine to ten weeks, the young owls can fly competently, though they remain dependent on their parents for food.

The family group stays together through the summer, with the young owls gradually improving their hunting skills through practice and observation. By fall, roughly six months after hatching, the young owls become independent and are driven out of the territory by their parents. These juvenile owls must then find their own territories, a perilous time when mortality is high. Many young owls die during this dispersal period, unable to find adequate territory or falling victim to starvation, predators, or accidents.

Great Horned Owls reach sexual maturity at two years of age, though they may not successfully breed until they’ve established their own territory. In the wild, those individuals that survive the dangerous juvenile period typically live 13-15 years, though some wild owls have been documented living over 20 years. In captivity, where they’re protected from the hazards of wild life, Great Horned Owls have lived 28 years or more, with some individuals reaching their early thirties.

Population

The Great Horned Owl is currently classified as “Least Concern” by the International Union for Conservation of Nature, a designation that reflects the species’ large population size, extensive range, and stable population trend. This conservation status is reassuring and stands in stark contrast to many other bird species that face serious threats.

Estimating the exact population of a nocturnal, secretive bird across such a vast range is challenging, but the most recent comprehensive assessments suggest there are approximately 3.9-5.3 million Great Horned Owls in North America alone. When including Central and South American populations, the global population likely exceeds 6 million individuals. Partners in Flight, a consortium of organizations focused on bird conservation, estimates the North American breeding population at around 5.3 million, making them one of the more common owl species on the continent.

Population trends appear to be relatively stable across most of their range, though regional variations exist. Long-term breeding bird survey data suggests slight declines in some areas, particularly in the Great Plains and certain agricultural regions, likely due to habitat changes and intensified farming practices. Conversely, populations may be increasing in some suburban and exurban areas where development creates edge habitat and where prey species like rabbits and rodents thrive.

The species’ adaptability has been key to its conservation success. Unlike more specialized species that require specific habitat conditions, Great Horned Owls have proven remarkably capable of adjusting to human-modified landscapes. They persist in fragmented habitats, tolerate proximity to human activity better than many raptors, and exploit novel food sources in developed areas.

However, their “Least Concern” status shouldn’t breed complacency. While Great Horned Owls as a species aren’t in danger, they remain vulnerable to the same threats affecting many wildlife species: habitat loss, pesticides, vehicle strikes, and climate change. Certain subspecies with more restricted ranges may face localized threats even as the species overall remains secure. Continued monitoring and conservation efforts remain important to ensure these magnificent birds remain a common sight and sound across their range.

Conclusion

The Great Horned Owl stands as a testament to evolutionary success and ecological adaptability. From the frozen forests of Alaska to the tropical jungles of South America, these powerful predators have claimed their place as apex avian hunters across a staggering diversity of habitats. Their combination of strength, stealth, intelligence, and adaptability has allowed them not just to survive but to thrive in a rapidly changing world where many species struggle.

As we’ve explored, these remarkable birds are far more than just fearsome predators. They’re dedicated parents that nest in the depths of winter, complex communicators with varied vocalizations and behaviors, and important regulators of prey populations in their ecosystems. Their presence indicates healthy, functioning habitats where the intricate web of predator and prey relationships remains intact.

Yet even species as successful as the Great Horned Owl require our stewardship. Each time we choose rodent control methods that don’t poison the food chain, design infrastructure that reduces bird strikes, protect nesting trees and natural areas, or simply slow down on rural roads at dusk, we contribute to ensuring these magnificent owls continue to hunt in our forests and skies. The haunting hoot of a Great Horned Owl in the darkness is more than just a sound—it’s a connection to the wild, a reminder that despite all our changes to the landscape, nature’s ancient rhythms persist. Our challenge is to ensure that future generations inherit a world where the tiger of the sky still reigns supreme.

Scientific Name: Bubo virginianus

Diet Type: CarnivoreSize: 18-25 inches (46-63 cm) in length; wingspan 35-60 inches (89-152 cm)

Weight: 2-5.5 pounds (910-2500 grams)

Region Found: Throughout North, Central, and South America, from northern Alaska and Canada to Tierra del Fuego