Each fall, millions of delicate orange-and-black butterflies embark on one of nature’s most astonishing journeys—a multi-generational migration spanning up to 3,000 miles from Canada to the mountains of central Mexico. The monarch butterfly (Danaus plexippus) is more than just a beautiful insect fluttering through gardens; it’s a testament to the intricate complexity of evolution, a living GPS system that scientists are still working to fully understand, and a species whose fate has become intertwined with our own environmental choices. What makes these gossamer-winged travelers truly extraordinary is that no single butterfly completes the entire round-trip journey—instead, this epic migration is a relay race passed across generations, with butterflies that have never made the trip before somehow finding their way to the exact same trees their great-great-grandparents roosted in months earlier.

Facts

- Super Generation Survivors: While most monarch generations live only 2-6 weeks, the “super generation” that makes the fall migration to Mexico lives up to 8-9 months—nearly ten times longer than their ancestors—thanks to a state of reproductive diapause that allows them to conserve energy.

- Toxic Beauties: Monarchs are poisonous to most predators due to cardenolide toxins they sequester as caterpillars from milkweed plants; a single monarch can make a bird violently ill, teaching predators to avoid anything with that distinctive orange-and-black warning pattern.

- Navigation Mystery: Scientists have discovered that monarchs use a sophisticated time-compensated sun compass in their antennae combined with magnetic sensing to navigate, but the complete mechanism of how they find specific overwintering sites remains partially unsolved.

- Weight-Loss Champions: During their migration, monarchs lose approximately 30% of their body weight, burning through fat reserves while flying up to 100 miles per day.

- Ancient Globetrotters: While North American monarchs are famous for their migration, monarchs have also colonized islands across the Pacific and Atlantic oceans, including populations in Hawaii, Australia, New Zealand, and the Canary Islands, though these populations don’t migrate.

- Milkweed Specialists: Monarch caterpillars can only survive on milkweed plants (genus Asclepias), making them one of nature’s most specialized herbivores and creating an evolutionary arms race as some milkweed species have developed latex sap that can trap and kill young caterpillars.

- Four-Generation Journey: It takes four to five successive generations of monarchs to complete a full migration cycle—spring and summer butterflies head north while the fall generation returns south, with each generation playing a specific role in the annual journey.

Species

Classification:

- Kingdom: Animalia

- Phylum: Arthropoda

- Class: Insecta

- Order: Lepidoptera (butterflies and moths)

- Family: Nymphalidae (brush-footed butterflies)

- Subfamily: Danainae (milkweed butterflies)

- Genus: Danaus

- Species: Danaus plexippus

The monarch butterfly belongs to a group called milkweed butterflies, named for their caterpillars’ dependence on milkweed plants. Within Danaus plexippus, scientists recognize several subspecies. The most well-known is D. p. plexippus, the migratory North American monarch. D. p. megalippe is found in the Caribbean, Central America, and northern South America, and typically doesn’t migrate long distances. A third subspecies, D. p. portoricensis, is sometimes recognized in specific Caribbean locations, though its status as a distinct subspecies is debated.

The monarch’s closest relatives include other species in the Danaus genus, such as the queen butterfly (Danaus gilippus), which resembles a darker, less vibrant monarch and shares similar milkweed-feeding habits, and the soldier butterfly (Danaus eresimus). Worldwide, there are approximately a dozen Danaus species, most found in the Old World tropics, suggesting that monarchs are relative newcomers to the Americas in evolutionary terms.

Appearance

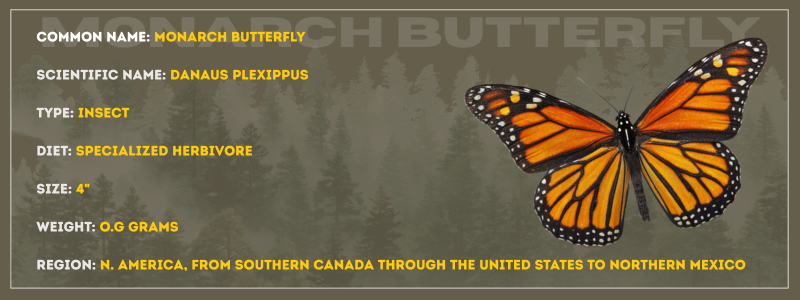

The monarch butterfly is instantly recognizable by its striking appearance. Adults have a wingspan ranging from 3.5 to 4 inches (8.9-10.2 cm), making them medium-to-large butterflies. Their wings display a bold pattern of bright orange panels divided by black veins, with black margins dotted with white spots. This high-contrast coloration serves as aposematic warning coloration, advertising the butterfly’s toxicity to potential predators.

Sexual dimorphism is subtle but present. Males possess two distinctive black spots on their hind wings—specialized scent glands called androconial patches that release pheromones during courtship. Females lack these spots and typically have thicker black veining on their wings. Males also tend to be slightly larger and have a more slender abdomen.

The monarch’s body is black with white spots on the thorax and head. Their antennae are long, thin, and clubbed at the end—a characteristic feature of butterflies as opposed to moths. An adult monarch weighs approximately 0.5 grams (about the weight of a paperclip), yet this seemingly fragile creature can travel thousands of miles.

Monarch caterpillars are equally distinctive, sporting bold bands of black, yellow, and white stripes running the length of their bodies. They possess two pairs of black filaments—one pair near the head and another near the rear—whose function remains somewhat mysterious, though they may serve a sensory role or help deter predators. A fully grown caterpillar reaches about 2 inches (5 cm) in length before pupating.

The chrysalis is perhaps the most beautiful stage, appearing as a pale green jewel-like structure adorned with gold dots. This stunning pupal case hangs from a silk pad, and the developing butterfly can sometimes be glimpsed through the increasingly transparent casing in the days before emergence.

Behavior

Monarch butterflies exhibit fascinating behavioral patterns that vary dramatically depending on their generation and life stage. Adult monarchs are primarily solitary and diurnal, active during daylight hours when they can regulate their body temperature through basking. Being cold-blooded, they require temperatures above 55°F (13°C) to fly effectively, and they’re often seen with wings spread wide in morning sunlight, warming their flight muscles.

During breeding season (spring and summer), monarchs are highly focused on reproduction and feeding. Males actively patrol areas rich in milkweed, searching for females. Courtship involves an aerial pursuit where the male chases the female, often forcing her to the ground where mating occurs. The male transfers a spermatophore containing both sperm and nutrients that will sustain the female during egg-laying.

The fall migratory generation displays dramatically different behavior. These butterflies enter reproductive diapause—their reproductive organs remain undeveloped, allowing them to conserve energy for the long journey ahead. They become intensely focused on feeding, building up fat reserves that will fuel their migration and sustain them through winter. Unlike their short-lived summer ancestors, these butterflies resist mating and dedicate themselves entirely to the journey south.

Once in their overwintering sites, monarchs display remarkable clustering behavior. Thousands to millions of butterflies congregate on the same trees, forming spectacular living blankets that drape from branches. This clustering serves multiple purposes: conserving heat, maintaining humidity, and providing protection from predators (there’s safety in numbers). Within these clusters, monarchs enter a state of semi-dormancy, remaining relatively inactive except on warmer days when they may fly to water sources.

Communication in monarchs is primarily chemical and visual. Males use pheromones to attract females, and the bright wing coloration communicates toxicity to predators. Recent research suggests monarchs may also use visual cues to recognize optimal habitats and possibly even to locate other monarchs during migration and overwintering.

Monarchs demonstrate surprising learning abilities for insects. They can learn to avoid plants that don’t provide adequate nutrition, remember flower locations, and even show evidence of learning from unsuccessful egg-laying attempts on unsuitable host plants.

Evolution

The evolutionary history of monarch butterflies is a fascinating story of adaptation and dispersal. Butterflies as a group (Lepidoptera) emerged during the Cretaceous period, roughly 100-130 million years ago, though the Nymphalidae family to which monarchs belong appeared much later.

The genus Danaus likely originated in the Old World tropics, with ancestors of modern monarchs probably originating in the Indo-Australian region. Genetic and biogeographic evidence suggests that the monarch butterfly colonized the Americas relatively recently in evolutionary terms—perhaps only within the last few million years, and possibly as recently as the Pleistocene epoch (2.6 million to 11,700 years ago).

The monarch’s remarkable migration likely evolved as populations expanded northward following the last ice age. As the climate warmed and milkweed species colonized temperate North America, monarchs followed their host plants north. However, these butterflies could not survive harsh northern winters, creating selective pressure for a migration strategy. Those butterflies with genetic traits enabling long-distance flight, fat storage, and the ability to navigate to suitable overwintering sites survived to pass on their genes.

The evolution of the monarch’s relationship with milkweed represents a classic example of coevolution. Milkweeds produce toxic cardiac glycosides (cardenolides) as a defense against herbivores. Ancestral monarchs evolved the ability to sequester and tolerate these toxins, turning the plant’s defense into their own protection against predators. This specialization created an evolutionary arms race, with some milkweed species evolving additional defenses like sticky latex sap, while monarchs developed counter-adaptations.

The famous orange-and-black warning coloration evolved through natural selection as predators learned to associate these colors with the butterfly’s toxicity. This pattern has become so effective that several other butterfly species, including the viceroy (Limenitis archippus), have evolved to mimic the monarch’s appearance—a phenomenon called Batesian mimicry (or in the viceroy’s case, possibly Müllerian mimicry, as viceroys may also be unpalatable).

Interestingly, different monarch populations show distinct evolutionary adaptations. Non-migratory island populations have evolved smaller wing sizes since they don’t need enhanced flight capabilities, while North American migratory monarchs have maintained larger wings and stronger flight muscles.

Habitat

Monarch butterflies occupy a remarkable geographic range across the Americas, with smaller introduced or naturally colonized populations scattered globally. The primary population centers on North America, where monarchs breed across a vast territory spanning from southern Canada through the United States and into northern Mexico.

The breeding habitat of monarchs is defined primarily by the presence of milkweed plants. During spring and summer, these butterflies inhabit a diverse array of environments including meadows, prairies, grasslands, roadsides, agricultural field margins, gardens, and disturbed areas where milkweed thrives. They show particular affinity for open or semi-open habitats with abundant flowering plants for nectar and milkweed for egg-laying. Monarchs are habitat generalists in this sense, adapting to various ecosystems from sea level to elevations around 10,000 feet, as long as their host plants are present.

The migration creates two distinct seasonal habitat requirements. Eastern North American monarchs—comprising the vast majority of the continental population—funnel toward a small mountainous region in the states of Michoacán and México in central Mexico. Here, they overwinter in oyamel fir (Abies religiosa) forests at elevations between 9,800 and 11,800 feet (3,000-3,600 meters). These specific forests provide ideal microclimatic conditions: cool enough to maintain the butterflies’ dormancy and conserve energy, but not so cold that they freeze; humid enough to prevent desiccation; and sheltered enough to protect from storms.

Western North American monarchs, a much smaller population, migrate to coastal California, overwintering in groves of eucalyptus, Monterey pine, and Monterey cypress trees along the Pacific coast, primarily between San Francisco and San Diego.

Non-migratory monarch populations exist in southern Florida, parts of the Caribbean, Central America, and South America, where mild year-round temperatures allow continuous breeding. Additionally, monarchs have established populations in Hawaii (arrived in the 1840s), Australia, New Zealand, Spain’s Canary Islands, Portugal, and scattered Pacific islands. These populations occupy tropical and subtropical habitats where milkweed species grow year-round.

The monarch’s habitat requirements highlight the species’ vulnerability: they need healthy ecosystems across vast geographic areas, from breeding grounds to migratory corridors to overwintering sites, with the loss of habitat in any single area potentially devastating entire populations.

Diet

Monarch butterflies have distinctly different dietary requirements depending on their life stage, exemplifying the complete metamorphosis characteristic of Lepidoptera.

As caterpillars, monarchs are specialized herbivores, feeding exclusively on plants in the milkweed family (Asclepias and related genera in the Apocynaceae family). This extreme dietary specialization makes monarchs “obligate milkweed feeders”—caterpillars cannot survive on any other food source. Different monarch populations feed on different milkweed species based on geographic availability. In North America alone, there are over 70 native milkweed species, including common milkweed (Asclepias syriaca), swamp milkweed (A. incarnata), butterfly weed (A. tuberosa), and tropical milkweed (A. curassavica).

Caterpillars possess powerful mandibles that allow them to consume milkweed leaves voraciously. A single caterpillar can consume approximately 20 milkweed leaves during its larval stage, increasing its body mass by about 2,000 times in just two weeks. The caterpillar’s digestive system has evolved to process the toxic cardenolides in milkweed without harm, and these toxins are sequestered in the caterpillar’s body, making it toxic to predators—a defense that carries through to the adult butterfly.

Adult monarchs are nectarivores, feeding exclusively on nectar from a wide variety of flowering plants. They are not specialists as adults, visiting dozens of flower species including milkweed (though they don’t need it for survival), asters, goldenrod, ironweed, blazing star, coneflowers, zinnias, marigolds, and many others. Monarchs show preference for flowers with high nectar content and those in colors they can easily see—particularly purple, pink, orange, and yellow blooms.

Adult monarchs feed using their long, coiled proboscis—a tube-like mouthpart that unrolls to reach deep into flowers. They can taste with their feet, allowing them to identify suitable nectar sources upon landing. During migration, monarchs strategically feed at nectar-rich sites, with fall migrants consuming more nectar to build critical fat reserves for their journey and winter dormancy.

Interestingly, adult monarchs also occasionally engage in “puddling”—drinking from mud puddles, damp soil, or animal feces to obtain minerals and salts, particularly sodium, which may be important for reproduction and neural function.

Predators and Threats

Despite their toxicity, monarch butterflies face numerous natural predators and increasingly serious anthropogenic threats that jeopardize their survival.

Natural Predators: While many animals learn to avoid monarchs after experiencing their unpalatable taste, several predators have evolved tolerance or strategies to consume them. Black-headed grosbeaks and black-backed orioles at Mexican overwintering sites are the monarchs’ most significant avian predators, having evolved resistance to cardenolide toxins. These birds carefully consume monarchs, sometimes targeting less toxic body parts. Mice also prey on overwintered monarchs, particularly weakened individuals.

During earlier life stages, monarchs face additional predators. Eggs and caterpillars are vulnerable to various insects including assassin bugs, lacewing larvae, lady beetles, and spiders. Some predators, like the Chinese mantis, can consume toxic caterpillars without apparent harm. Parasitoids, particularly tachinid flies and braconid wasps, lay eggs in or on monarch caterpillars and eggs, with the parasitoid larvae eventually consuming their host.

Certain caterpillar predators have evolved remarkable strategies to avoid toxins. Some beetles cut the milkweed leaf’s midrib before feeding, causing the latex sap to drain, reducing both the sticky sap and toxin content.

Anthropogenic Threats represent far more serious and existential risks to monarch populations:

Habitat Loss is the primary threat. In North America, over 165 million acres of monarch habitat have been lost to agricultural expansion, urban development, and changing land use practices. The widespread adoption of herbicide-resistant crops has led to extensive herbicide use that eliminates milkweed from agricultural landscapes where it once thrived. Roadside maintenance practices and development have removed milkweed from these traditional corridors.

In Mexico, illegal logging and degradation of oyamel fir forests in overwintering sites, despite protected status, reduces the forest canopy that provides crucial microclimate regulation. When canopy cover falls below critical thresholds, monarchs become vulnerable to freezing and desiccation.

Climate Change affects monarchs in multiple ways. Extreme weather events during migration can kill millions of butterflies. Drought reduces milkweed and nectar plant availability. Shifting temperature and precipitation patterns may cause phenological mismatches—monarchs arriving when food plants haven’t yet emerged or have already senesced. Climate change also threatens the delicate microclimate conditions of overwintering forests in Mexico.

Pesticides pose both direct and indirect threats. Neonicotinoid insecticides can kill monarchs directly or cause sublethal effects that impair navigation, reproduction, and survival. Herbicides eliminate milkweed, the caterpillars’ only food source. Even home garden pesticides contribute to monarch mortality.

Tropical Milkweed Planting has created an unexpected conservation challenge. While well-intentioned, year-round planting of non-native tropical milkweed (Asclepias curassavica) in southern regions can disrupt migration by providing resources that encourage monarchs to breed continuously rather than migrate. This non-native milkweed can also harbor higher levels of the debilitating protozoan parasite Ophryocystis elektroscirrha.

Light Pollution may interfere with monarchs’ celestial navigation during migration, though research on this threat is still emerging.

Reproduction and Life Cycle

Monarch butterflies undergo complete metamorphosis, with four distinct life stages: egg, larva (caterpillar), pupa (chrysalis), and adult. Their reproductive strategy and life cycle timing vary dramatically between generations.

Mating in monarchs involves complex courtship behavior. Males patrol areas searching for females, often engaging in aerial pursuits. When a male locates a receptive female, he pursues her through the air, often grasping her mid-flight. The pair descends to the ground or vegetation where actual mating occurs. During copulation, which can last from 30 minutes to several hours, the male transfers a spermatophore—a package containing sperm and nutrients. This nuptial gift provides the female with proteins and other resources that support egg production.

Males employ specialized pheromone-producing scales on their hind wings (the androconial patches) during courtship, releasing chemical signals that may help secure mating. Females often mate multiple times, though a single mating provides sufficient sperm for her entire lifetime of egg-laying.

Egg-Laying: After mating, females search meticulously for milkweed plants, testing leaves by drumming them with their forelegs, which have chemoreceptors that identify suitable host plants. A female typically lays a single egg on the underside of a young milkweed leaf—a strategy that provides the emerging caterpillar with tender, nutritious foliage and reduces competition between siblings. Over her lifetime, a female may lay 300-500 eggs, though only a small fraction will survive to adulthood.

The eggs are tiny (about 1.2 mm tall), cream-colored, and intricately ridged. The egg stage lasts approximately 3-5 days, depending on temperature.

Larval Stage: The newly hatched caterpillar’s first meal is usually its own eggshell, which provides nutrients and possibly probiotic bacteria. The caterpillar then begins feeding voraciously on milkweed leaves. Over 9-14 days, it progresses through five instars (growth stages), molting its skin each time. With each molt, the distinctive black, white, and yellow striped pattern becomes more pronounced.

Pupal Stage: When ready to pupate, the mature caterpillar (about 2 inches long) stops eating and searches for a safe location—often away from the milkweed plant to avoid attracting predators to remaining caterpillars. It spins a small silk pad on a horizontal surface and attaches itself upside down in a characteristic “J” shape. Within about 24 hours, the caterpillar molts a final time, revealing the jade-green chrysalis with its metallic gold dots.

Inside the chrysalis, the caterpillar’s body undergoes remarkable reorganization. Most larval structures dissolve, and adult structures develop from clusters of cells called imaginal discs. This transformation takes 10-14 days. As emergence approaches, the chrysalis becomes transparent, revealing the monarch’s orange and black wings inside.

Adult Emergence: The butterfly breaks through the chrysalis casing and pulls itself free. Its wings are initially soft and crumpled. The butterfly pumps hemolymph (insect blood) into the wing veins, expanding them to full size. Over several hours, the wings harden. Once ready, the monarch takes its first flight.

Generational Differences: Spring and summer generations (the first through third or fourth generations) complete their entire life cycle in about 4-6 weeks and live as adults for only 2-6 weeks. These butterflies are reproductively active immediately and focus on breeding and moving northward.

The fall migratory generation is dramatically different. These monarchs emerge in late summer/early fall and can live 8-9 months. They remain reproductively immature, don’t mate, and instead build fat reserves and migrate to overwintering sites. After overwintering, they become reproductively active, mate, and begin the northward migration, laying eggs along the way before dying. This super generation’s extended lifespan results from reproductive diapause triggered by decreasing day length and cooler temperatures during their development.

Lifespan: As noted, lifespan varies dramatically by generation—2-6 weeks for summer generations, up to 9 months for the migratory generation. Overall, the complete migration cycle spans 4-5 generations annually.

Population

The conservation status and population trends of monarch butterflies paint a concerning picture, though the outlook varies between populations.

Conservation Status: The migratory monarch butterfly’s status has been the subject of intense debate and advocacy. In 2024, the eastern North American monarch migration was listed as Endangered on the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List, while the western North American population was listed as Critically Endangered. However, in the United States, despite being a candidate for listing under the Endangered Species Act, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service has not yet granted federal protection, citing other species as higher priorities.

Non-migratory resident populations in various locations are not separately assessed but generally face less dramatic declines.

Population Estimates and Trends: Monarch populations are typically measured differently depending on the population:

For the eastern North American population (the largest), scientists measure the area of forest occupied at Mexican overwintering sites rather than counting individual butterflies. Historical estimates from the mid-1990s documented overwinter populations covering approximately 20.9 hectares (about 52 acres) of forest. By the winter of 2013-14, this had plummeted to just 0.67 hectares—a decline of approximately 97% and representing a population of perhaps only 35 million butterflies.

Recent years have shown fluctuation rather than consistent recovery. The winter of 2022-23 saw approximately 2.21 hectares occupied (roughly 138 million butterflies), but the 2023-24 season dropped to 2.2 hectares. While above the crisis lows of 2013-14, populations remain approximately 85% below historical baseline levels. Scientists estimate that 6 hectares represents the minimum threshold for long-term population stability.

The western North American population has experienced even more catastrophic declines. Historical estimates suggested 10 million butterflies at California overwintering sites in the 1980s. By 2020, fewer than 2,000 butterflies were counted—a decline of more than 99%. The 2021-22 season showed signs of recovery with approximately 250,000 butterflies counted, followed by roughly 330,000 in 2022-23, but these numbers remain a tiny fraction of historical abundance.

Factors Driving Decline: The dramatic population reductions result from the cumulative threats described earlier—habitat loss, particularly the widespread elimination of milkweed from agricultural landscapes; climate-driven extreme weather events; pesticide exposure; and degradation of overwintering sites.

Conservation Efforts: Numerous initiatives aim to reverse monarch declines. These include large-scale milkweed restoration programs, protection and reforestation of Mexican overwintering sites, reduced herbicide use in rights-of-way, pollinator-friendly agricultural practices, and citizen science monitoring programs. The establishment of pollinator gardens and corridors shows promise, though coordinated action at landscape scales is essential for population recovery.

Conclusion

The monarch butterfly represents one of nature’s most extraordinary achievements—a fragile creature weighing less than a gram that navigates thousands of miles using sophistication that rivals our best technology, all programmed in a brain smaller than a pinhead. Yet this same butterfly embodies our current conservation crisis: a species whose survival depends not on a single protected park but on the health of entire landscapes spanning a continent.

The monarch’s story teaches us that nature’s most remarkable phenomena often depend on intricate connections—between butterfly and milkweed, between generations separated by time, between forests in Mexico and prairies in Canada. When we sever these connections through habitat destruction, pesticide use, and climate change, we don’t just lose a beautiful butterfly; we lose a living symbol of the interconnectedness that sustains all life.

The encouraging news is that monarch conservation is something everyone can support. Planting native milkweed, avoiding pesticides, supporting habitat restoration, and advocating for pollinator-friendly policies all contribute to monarch recovery. Every garden can become a waystation, every yard a refuge. The monarch butterfly’s future remains uncertain, but unlike many conservation challenges, this is one where individual actions genuinely matter. The question is whether we’ll act with the urgency this extraordinary migrant deserves—before the miracle of millions of butterflies draping Mexican forests becomes merely a memory of natural wonders we failed to preserve.