Imagine a living tide, stretching for miles across the frozen, vast expanse of the Arctic tundra. This is the magnificent spectacle of the caribou (or reindeer), one of the most iconic and resilient mammals on Earth. These animals are the true nomads of the north, undertaking the longest terrestrial migrations of any land animal, navigating immense distances in their constant search for food and safe calving grounds.

The caribou isn’t just significant for its breathtaking journeys; it is an ecological linchpin in the fragile northern ecosystem and a cultural cornerstone for Indigenous peoples. Its ability to thrive in the world’s harshest environments, possessing an array of incredible biological adaptations, makes it an absolutely fascinating subject. Let’s delve into the world of this Arctic trailblazer!

Quick Caribou Facts 🤯

Here are some intriguing tidbits about the caribou you might not know:

- Antlers on the Ladies: The caribou is the only species of deer where both males and females regularly grow antlers. Females often retain theirs through the winter, giving them a competitive edge for food.

- Built-in Snowshoes: Their hooves are large and crescent-shaped, acting like shovels in the snow to dig for lichen, and providing excellent traction on ice. In the summer, the hoof pads soften for better grip on soft tundra.

- Crackling Knees: As they walk, caribou often produce a distinctive “clicking” sound. This comes from a tendon slipping over a bone in their ankles, which is thought to help the herd stay together in whiteout conditions or fog.

- Floating on Water: The caribou’s thick, double-layered coat is made of hollow hairs, which trap air and provide incredible buoyancy. This makes them surprisingly adept swimmers, able to cross wide, frigid rivers and even open ocean channels.

- Ultraviolet Vision: Caribou can see in the ultraviolet (UV) spectrum. This ability is crucial for spotting predators like white wolves against the uniformly white snow, which reflects UV light. It also helps them find nutrient-rich lichen that might be hidden under the snow.

Species and Classification 🧐

The caribou belongs to the deer family (Cervidae), but its classification reveals its unique place among its relatives.

| Category | Classification |

| Kingdom | Animalia |

| Phylum | Chordata |

| Class | Mammalia |

| Order | Artiodactyla |

| Family | Cervidae (Deer) |

| Genus | Rangifer |

| Species | R. tarandus |

The scientific name, Rangifer tarandus, encompasses all caribou and reindeer. While the names are often used interchangeably, generally reindeer refers to the domesticated form found mostly in Eurasia, and caribou refers to the wild populations in North America (though some wild forms in Eurasia are also called reindeer).

The species is generally divided into two main ecotypes in North America, each with several subspecies:

- Tundra Caribou: These include the large herds that undertake the great migrations, such as the Barren-ground Caribou (R. t. groenlandicus) and Porcupine Caribou (R. t. grantii).

- Woodland Caribou: These are typically larger, darker, and live in smaller groups, migrating shorter distances. The most threatened ecotype is the Boreal Woodland Caribou (R. t. caribou).

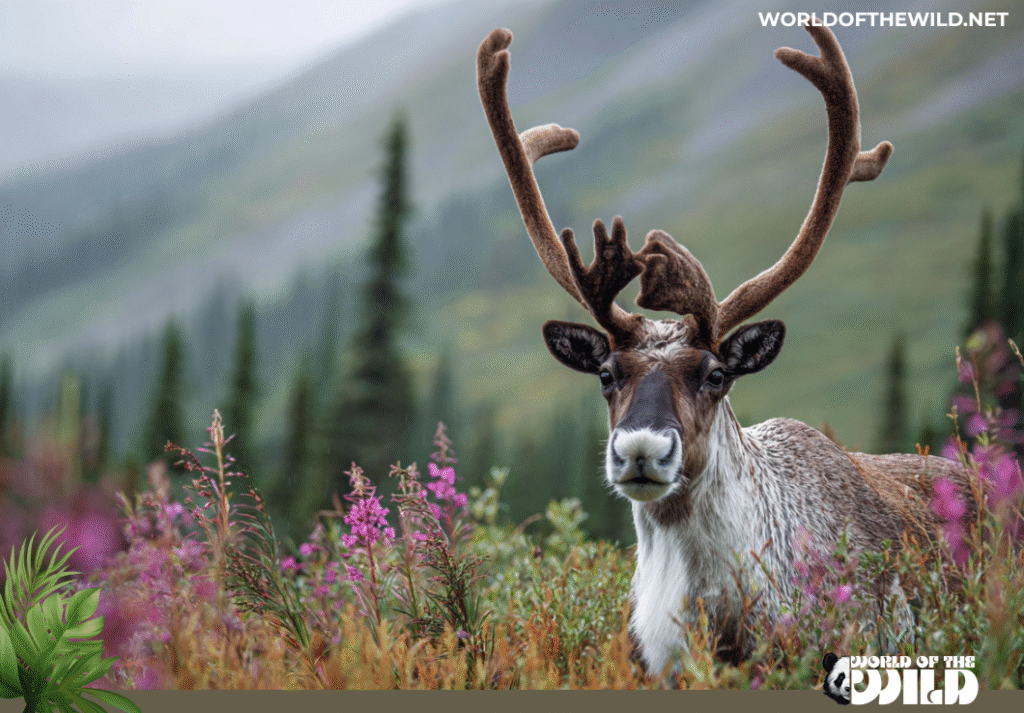

Appearance 📏

The caribou is built for the cold, possessing a robust and powerful physique.

- Size and Weight: They are a medium to large species of deer. Bulls (males) can stand over 4 feet (1.2 meters) tall at the shoulder and weigh between 350 to 400 pounds (160 to 180 kg), though some can reach 700 pounds (320 kg). Cows (females) are generally smaller.

- Color and Fur: Their coat is incredibly dense and double-layered. The color ranges from white or light gray in the winter to a darker, brownish-gray in the summer. A distinctive feature is the white mane that hangs down from the neck and the whitish patch above the hooves.

- Antlers: The antlers of caribou are the largest and heaviest of all deer relative to body size. They have a characteristic shovel-like projection called a brow tine or ‘palmate’ that extends forward over the face. Antlers are shed and regrown annually; males typically shed theirs in the early winter, while non-pregnant females shed theirs in the spring.

Behavior 🧭

Caribou are primarily gregarious animals, meaning they live in groups. The tundra ecotype forms massive herds that can number in the tens of thousands to hundreds of thousands—an incredible survival mechanism against predators.

- Migration: Their defining behavior is their annual long-distance migration. They move from winter ranges in the forest or sheltered valleys to summer calving grounds on the open tundra, covering up to 3,000 miles (5,000 km) round trip. This movement is driven by the seasonal availability of food and the need to escape insects and predators.

- Communication: Caribou communicate through a variety of sounds, including grunts, snorts, and bellowing roars, especially during the mating season (the rut). Non-verbal communication, such as posturing and scent marking, is also vital.

- Energy Conservation: In the winter, caribou have a remarkable adaptation: they can lower their body temperature in their legs and feet close to the freezing point. This adaptation minimizes heat loss and allows them to maintain a warmer core temperature, conserving vital energy.

Evolution 🧬

The genus Rangifer has an extensive and successful evolutionary history, closely linked to the Ice Ages.

- Pleistocene Origins: The ancestors of modern caribou evolved in the Pleistocene epoch (beginning about 2.5 million years ago). They were supremely adapted to the cold, treeless, periglacial environments (areas bordering glaciers).

- Widespread Distribution: Fossil evidence shows that caribou or very closely related species were once found much further south in North America and across Eurasia than they are today. The extinct Irish Elk (Megaloceros giganteus)—while not a direct ancestor—is an example of a giant deer that shared the same cold-adapted environment as early Rangifer.

- Survival through Glaciation: The caribou’s ability to live on low-quality forage (like lichen) and undertake long migrations allowed it to survive the climatic shifts of the Quaternary glaciations that drove many other large mammals to extinction. Its current distribution is a remnant of this massive, Ice Age range.

Habitat 🧊🌲

The caribou is a species of the Circumpolar North, found across the northern regions of North America, Greenland, Europe, and Asia.

- Geographic Range: In North America, they stretch from Alaska and Yukon down through parts of Canada.

- Specific Environments:

- Tundra: The primary summer range for the great herds. This is a vast, treeless, cold biome characterized by permafrost (permanently frozen ground) and low-growing vegetation like mosses, grasses, and shrubs.

- Boreal Forest (Taiga): The primary winter range and permanent habitat for the Woodland caribou ecotype. This is a coniferous forest region south of the tundra, providing crucial shelter from deep snow and predators.

The defining feature of their habitat is the extreme seasonal variation in temperature, light, and food availability, which necessitates their nomadic lifestyle.

Diet 🌿

Caribou are herbivores, meaning their diet consists entirely of plant matter. Their diet changes significantly between summer and winter.

- Summer Diet: During the brief but lush summer, caribou feed primarily on tender grasses, sedges, leaves of dwarf shrubs, and mushrooms. This is a crucial time for building up fat reserves.

- Winter Diet: The primary food source in winter is lichen, often called “reindeer moss.” Lichen is low in protein but high in carbohydrates, making it an essential survival food. They use their large hooves to dig through deep snow—a behavior called cratering—to find this vital forage.

Predators and Threats 🐺

The caribou faces both natural and human-made challenges to its survival.

Natural Predators

The main natural predators of the caribou are large carnivores native to the northern regions:

- Gray Wolves (Canis lupus) are the most significant predator, often hunting caribou in packs.

- Grizzly Bears (Ursus arctos horribilis) and Polar Bears (Ursus maritimus) prey on caribou, particularly the vulnerable calves during the spring calving season.

- Wolverines (Gulo gulo) occasionally prey on calves, sick, or injured adults.

Anthropogenic Threats

- Climate Change: This is the most pressing threat. Warming temperatures increase the frequency of freezing rain events, creating thick layers of ice on the snow. This locks away the lichen, making it impossible for the caribou to access their winter food.

- Habitat Fragmentation: Linear disturbances like mining roads, pipelines, and seismic lines associated with resource extraction break up critical habitat and migration routes. These clearings can also provide wolves with easier travel corridors into caribou range.

- Industrial Activity: Increased oil and gas exploration and mining disturb calving grounds and migratory patterns, causing stress and reproductive failure.

Reproduction and Life Cycle 🍼

The life cycle of the caribou is timed perfectly to the Arctic’s short window of opportunity.

- Mating (Rut): The mating season occurs in the fall (September to October). Bulls engage in fierce fights, locking antlers to establish dominance and gain access to harems of cows.

- Gestation: The gestation period lasts about 7.5 months (225–235 days).

- Calving: The birth of calves happens in late spring (May to June) on traditional, open calving grounds. This is timed to coincide with the flush of new spring growth. Cows typically give birth to a single calf, rarely twins.

- Offspring: A newborn calf is extremely precocial (advanced at birth) and can stand and even run within a few hours. This rapid mobility is essential for escaping predators. Parental care is intense, with the cow aggressively defending her calf for its first year.

- Lifespan: Caribou can live for 15 to 20 years in the wild, though many do not survive their first year.

Population and Status 🚨

The caribou’s conservation status is a mosaic of hope and serious concern, depending on the subspecies and region.

- Global Conservation Status (IUCN): Vulnerable (VU).

- Global Population Estimate: The total world population of wild caribou is difficult to estimate precisely but is generally considered to be in the millions, although many of the largest herds have seen catastrophic declines.

- Population Trends: Unfortunately, the dominant trend is one of significant decline. Many major North American migratory herds have seen their numbers plummet by as much as 70-80% in recent decades. The Boreal Woodland Caribou of Canada is classified as Threatened due to habitat loss and fragmentation, making its status particularly precarious.

Conclusion 🌟

The caribou is more than just a large deer; it is a symbol of the resilience and sheer wildness of the Arctic. Its sweeping migrations and sophisticated adaptations—from its clicking ankles to its ultraviolet vision—paint a picture of an animal perfectly tuned to a challenging world.

Yet, this iconic creature is now facing an unprecedented threat from the modern world, primarily through the dual pressures of climate change and human development. The decline of the great herds is a stark warning of the environmental changes gripping the North.

The fate of the caribou is intertwined with the health of the vast, fragile tundra ecosystem. We must recognize that protecting their immense migratory pathways and sheltered forests is not just about saving one species, but about preserving an entire natural wonder. The long, winding trail of the caribou is worth fighting for.