Perched motionlessly on a sun-drenched branch, a chameleon rotates one eye backward to scan for predators while the other fixes forward on an unsuspecting cricket. In an explosive burst lasting mere hundredths of a second, its tongue—longer than its entire body—rockets outward with acceleration that would make a fighter jet pilot black out. The cricket never stood a chance.

Chameleons are among nature’s most captivating enigmas, creatures that seem almost too fantastical to be real. While most people associate them solely with color-changing abilities, these remarkable reptiles possess an arsenal of adaptations that challenges our understanding of what’s possible in the animal kingdom. From eyes that move independently to feet designed like living grappling hooks, chameleons represent one of evolution’s most specialized and successful experiments in arboreal hunting. Understanding these ancient reptiles offers us a window into the extraordinary creativity of natural selection and reminds us of the irreplaceable biodiversity we must protect.

Facts

Here are some captivating facts about chameleons that go beyond the familiar:

- Ballistic tongue hunters: A chameleon’s tongue can accelerate at over 250 meters per second squared—roughly five times faster than a fighter jet launching from an aircraft carrier—and reaches its prey in just 0.07 seconds.

- Color change isn’t just camouflage: Chameleons primarily change color to communicate emotions, regulate body temperature, and signal during courtship or territorial disputes rather than to blend into backgrounds.

- 360-degree vision: Their independently moving eyes provide a complete field of vision around their bodies, and they can focus both eyes on a single target for precise depth perception when hunting.

- No external or middle ear: Despite lacking traditional ear openings and eardrums, chameleons can detect sound frequencies between 200-600 Hz through bone conduction and specialized structures.

- Miniature to massive diversity: The world’s smallest chameleon, Brookesia micra, measures just over half an inch, while the largest, the Parson’s chameleon, can reach nearly 27 inches in length—a 50-fold size difference within one family.

- Ancient lineage: Chameleons have existed for approximately 65-90 million years, meaning they shared the planet with dinosaurs and witnessed their extinction.

- Zygodactyl feet: Their feet are fused into opposing bundles—two toes on one side, three on the other—creating a vise-like grip perfectly adapted for gripping branches.

Species

Classification:

- Kingdom: Animalia

- Phylum: Chordata

- Class: Reptilia

- Order: Squamata

- Family: Chamaeleonidae

- Genera: Multiple, including Chamaeleo, Furcifer, Brookesia, Trioceros, and others

- Species: Approximately 200+ recognized species

The chameleon family encompasses remarkable diversity. Scientists recognize roughly 200 species divided into multiple genera, with new species still being discovered regularly, particularly among the miniature leaf chameleons of Madagascar.

The two largest genera are Furcifer (which includes the iconic Panther Chameleon and Parson’s Chameleon) and Chamaeleo (containing the Common Chameleon and Veiled Chameleon). The genus Brookesia comprises the fascinating miniature leaf chameleons, some barely larger than a fingernail. Trioceros includes numerous African species like the Jackson’s Chameleon, distinguished by its three prominent horns.

Geographic radiation has created distinct groups: Madagascar harbors about half of all chameleon species, making it the undisputed center of chameleon diversity. African chameleons span the continent from rainforests to savannas, while a handful of species reach into southern Europe, the Middle East, and South Asia. Some taxonomists also recognize Bradypodion, containing the dwarf chameleons of southern Africa, and Kinyongia, comprising montane species from East Africa.

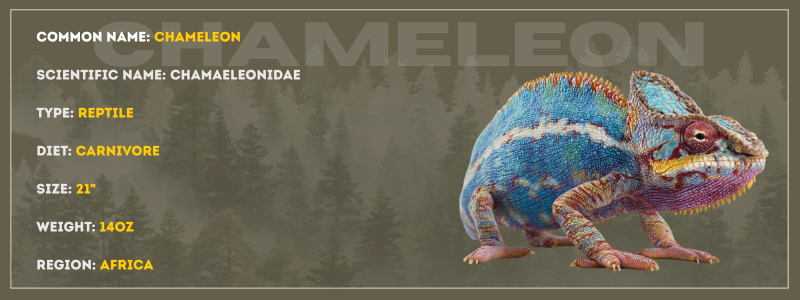

Appearance

Chameleons display extraordinary morphological diversity, yet all share unmistakable family characteristics. Body sizes range dramatically from the minute Brookesia micra at just 0.5 inches (1.3 cm) to the imposing Parson’s chameleon reaching 27 inches (68 cm). Most species fall within the 7-12 inch range. Weights vary correspondingly from less than a gram in miniature species to over 600 grams in the largest individuals.

Their distinctive body plan features a laterally compressed form—appearing flattened from side to side—which serves multiple purposes including intimidation displays and efficient thermoregulation. The head shapes vary remarkably: some species like the Veiled Chameleon sport elaborate casques (helmet-like crests), while others like Jackson’s Chameleon possess prominent horns resembling miniature triceratops. Female horned species typically have smaller or absent horns compared to males.

The prehensile tail functions as a fifth limb, capable of supporting the animal’s entire weight and providing stability during hunting. Interestingly, some ground-dwelling chameleons have reduced or non-prehensile tails, showing adaptive loss of this arboreal feature.

Chameleon eyes are perhaps their most striking feature: large, conical, and capable of rotating independently through nearly 180 degrees. A small circular opening in each scaly eyelid allows focused vision. When both eyes converge on prey, chameleons achieve exceptional stereoscopic vision for accurate distance calculation.

Their feet exhibit perfect zygodactyl adaptation—two toes fused together facing one direction, three facing the opposite—creating a powerful pincer grip. Sharp claws provide additional purchase on bark and branches.

Color patterns deserve special attention. Base coloration varies from brilliant greens and blues to subtle browns and grays, often featuring stripes, spots, or geometric patterns. The famous color-changing ability stems from specialized cells called chromatophores arranged in layers beneath the transparent outer skin. Beneath these lie iridophores containing nanocrystals that reflect light, and deepest are melanophores containing dark pigment. By adjusting crystal spacing in iridophores and dispersing or concentrating pigments in other layers, chameleons produce dramatic color shifts—from vibrant breeding displays to dark heat-absorbing blacks to pale stress colors.

Behavior

Chameleons exhibit fascinating behavioral patterns finely tuned to their predatory, arboreal lifestyle. Predominantly solitary creatures, they defend territories and typically interact only during breeding season. Males particularly demonstrate aggression toward rivals, using color displays, body inflation, hissing, and occasionally physical combat to establish dominance.

Their movement strategy exemplifies stealth hunting. Chameleons advance with characteristic slow, swaying motions that mimic leaves moving in the breeze, making them nearly invisible to both prey and predators. This rocking gait isn’t random—it helps them judge distance through motion parallax before committing to a tongue strike. However, when necessary, chameleons can move surprisingly quickly across branches.

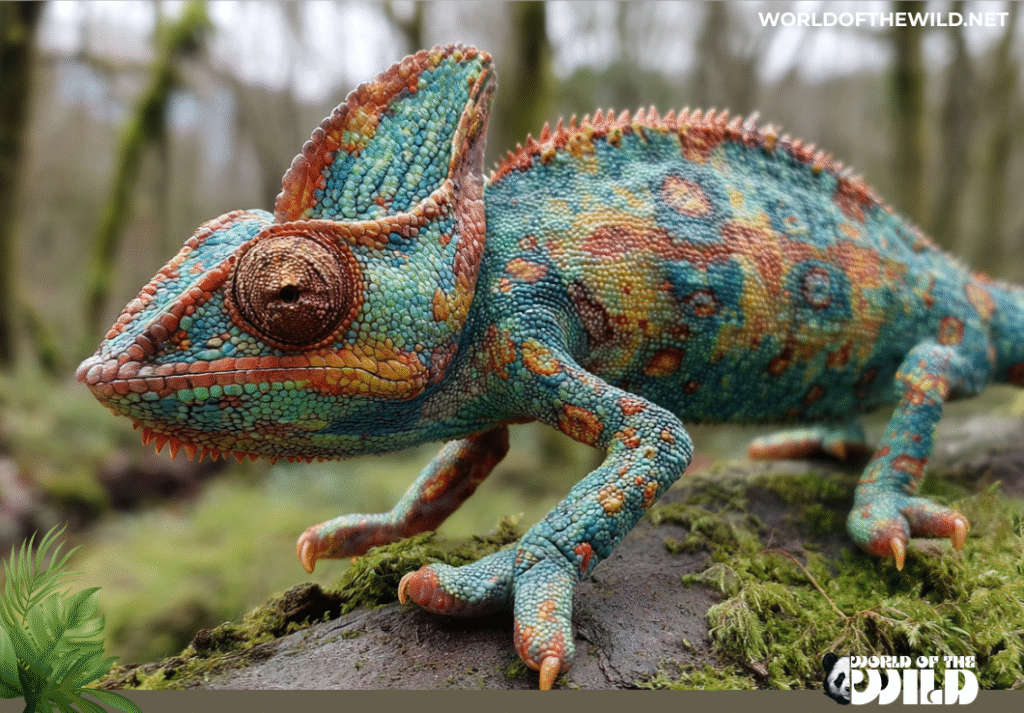

The hunting sequence showcases remarkable coordination. After visual acquisition of prey—with one eye often maintaining rear guard while the other focuses forward—the chameleon approaches within striking distance (typically 1-1.5 body lengths). The tongue launch involves sophisticated biomechanics: specialized accelerator muscles on a tapered bone create a catapult effect, projecting the tongue with incredible force. The sticky pad at the tongue’s tip uses both adhesive mucus and a suction cup mechanism to secure prey. The entire strike and retraction occurs in fractions of a second.

Communication relies heavily on visual signals. Color changes convey complex messages: bright colors often signal aggression or courtship readiness, dark colors may indicate submission or stress, and rapid color pulsing can signal extreme agitation. Some species combine color displays with physical movements like head bobbing, body swaying, or gaping their mouths to reveal brightly colored interior tissue.

Chameleons demonstrate notable intelligence for reptiles. They can learn to recognize individual humans, navigate complex three-dimensional environments, and even show problem-solving abilities in laboratory settings. Some species display what appears to be curiosity, investigating novel objects in their environment.

Sleep behavior involves finding secure perching spots where they grip branches tightly. While sleeping, chameleons become pale and vulnerable—though their grip remains strong even in deep sleep.

Thermoregulation drives much daily activity. As ectotherms, chameleons must carefully manage body temperature through behavior and color changes. Morning basking in sun-exposed locations warms them for activity, while darker colors absorb more heat. During midday heat, they may retreat to shade and display lighter colors that reflect solar radiation.

Evolution

Chameleons represent an ancient and highly specialized lineage within the suborder Iguania. Molecular and fossil evidence suggests the family Chamaeleonidae diverged from other lizard groups approximately 65-90 million years ago during the Late Cretaceous period, making them contemporary with the last dinosaurs.

The evolutionary origins remain somewhat debated, but most evidence points to an African genesis. The oldest definitive chameleon fossil, Anqingosaurus brevicephalus, dates to approximately 65 million years ago in China, though this represents a lineage that left no modern descendants. More relevant to modern chameleons are fossils from Europe dating to the Paleogene period (66-23 million years ago), suggesting the family was once more widespread.

A crucial evolutionary event occurred with the colonization of Madagascar. Genetic studies indicate chameleons reached this island continent relatively early—possibly through oceanic dispersal on floating vegetation, as Madagascar had already separated from Africa. Once there, adaptive radiation exploded into remarkable diversity. Today, Madagascar hosts approximately half of all chameleon species, ranging from tiny leaf chameleons to the massive Parson’s chameleon.

The evolution of chameleon specializations represents convergent refinement of traits found more primitively in other iguanian lizards. Prehensile tails, independently mobile eyes, and projectile tongues all evolved through modification of existing structures. The tongue mechanism particularly represents an evolutionary marvel—modified hyoid apparatus bones and specialized muscle arrangements create biomechanical properties found nowhere else in nature.

Color-changing ability evolved from chromatophores present in many reptile lineages, but chameleons developed unprecedented control and complexity. Recent research revealed that the iridophore nanocrystal system allowing structural color changes represents a unique chameleon innovation.

The miniaturization seen in dwarf and leaf chameleons demonstrates fascinating evolutionary trends. Some Brookesia species exhibit extreme miniaturization while retaining full functionality, pushing against the physical limits of vertebrate body plans. This evolutionary pathway likely resulted from advantages in accessing invertebrate prey and occupying microhabitats unavailable to larger predators.

Chameleons’ closest relatives include dragon lizards (Agamidae) and iguanas (Iguanidae), together forming the iguanian radiation that diverged from other squamates over 150 million years ago. This ancient split explains why chameleons seem so anatomically distinct from snakes and most other lizards.

Habitat

Chameleons inhabit diverse environments across Africa, Madagascar, southern Europe, the Middle East, and South Asia, with Madagascar and sub-Saharan Africa representing their primary strongholds. Their geographic distribution reflects ancient continental connections and more recent dispersal events.

The overwhelming majority of chameleon species are arboreal, dwelling in trees and shrubs where their specialized adaptations provide maximum advantage. They favor habitats with abundant vegetation including tropical and subtropical rainforests, montane cloud forests, coastal scrublands, savannas with scattered acacia trees, and riverine gallery forests penetrating drier regions.

In Madagascar’s rainforests, chameleons occupy various forest strata from the canopy to the understory, with species showing distinct preferences for particular heights and microhabitats. Some species specialize in secondary growth and forest edges, while others require pristine primary forest. The island’s eastern rainforest belt supports the highest chameleon diversity anywhere on Earth.

African species show broader habitat tolerance. The Veiled Chameleon thrives in the semi-arid mountains of Yemen and Saudi Arabia, demonstrating remarkable drought adaptation. Jackson’s Chameleon inhabits montane forests of East Africa at elevations reaching 10,000 feet, where cool temperatures and frequent fog prevail. The Common Chameleon ranges across Mediterranean scrubland and coastal North Africa into the Iberian Peninsula—Europe’s only native chameleon population.

Not all chameleons are tree-dwellers. The genus Brookesia (leaf chameleons) includes numerous terrestrial species inhabiting forest floor leaf litter. These diminutive chameleons rarely climb, instead navigating through the complex understory environment where their brown coloration provides excellent camouflage against dead leaves.

Chameleons require specific microhabitat features: appropriate perching sites for hunting and sleeping, exposure to sunlight for thermoregulation, access to standing water droplets on leaves for drinking (they rarely drink from standing water), and sufficient prey populations. Dense vegetation provides security from predators while offering hunting opportunities.

Elevation ranges vary dramatically among species. Some coastal species remain near sea level, while montane specialists like certain Trioceros and Kinyongia species occur exclusively above 6,000 feet. Temperature and humidity gradients associated with elevation create distinct ecological zones, and chameleons have radiated to fill available niches throughout these gradients.

Human-modified landscapes present mixed outcomes. Some generalist species like Flap-necked Chameleons readily inhabit gardens, orchards, and agricultural areas. However, most species require relatively intact native vegetation and decline rapidly following habitat modification.

Diet

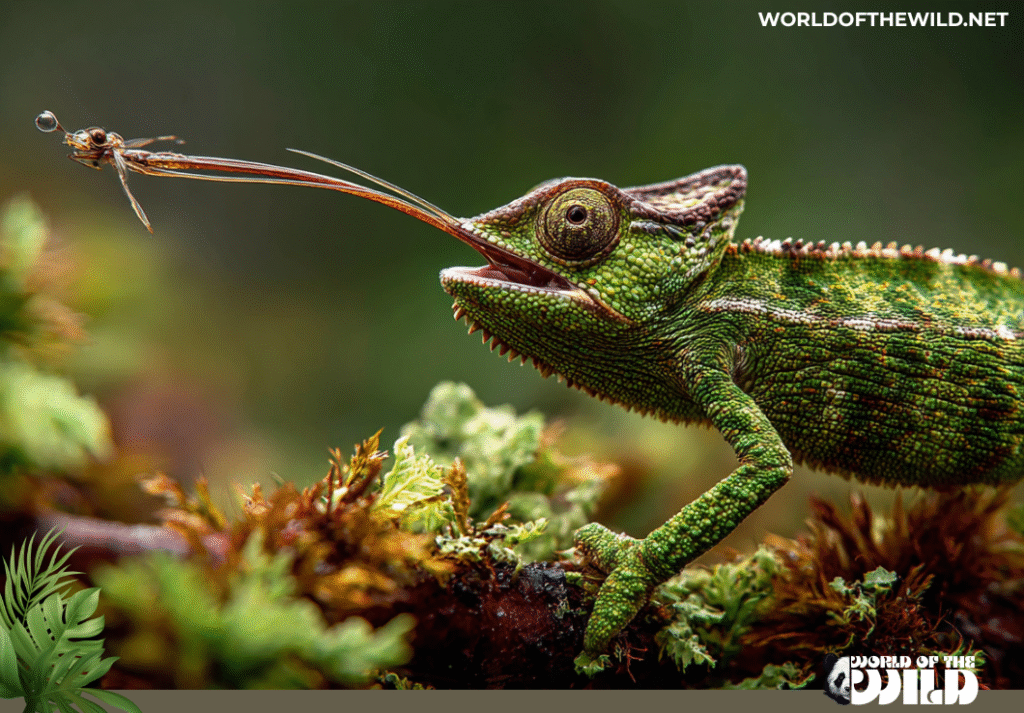

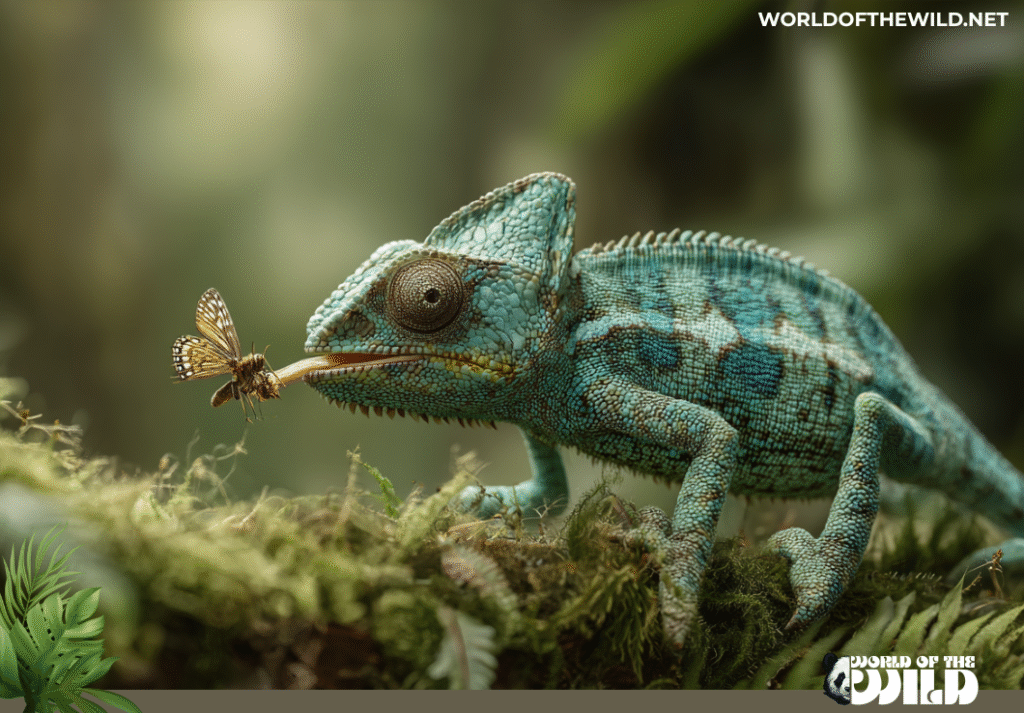

Chameleons are overwhelmingly carnivorous, functioning as specialized predators of invertebrates and, in larger species, small vertebrates. Their entire morphology—from stereoscopic vision to ballistic tongue—evolved to support this predatory lifestyle.

The primary dietary staples across most chameleon species include crickets, grasshoppers, locusts, flies, beetles, butterflies, moths, mantises, stick insects, roaches, and spiders. Larger chameleon species occasionally consume small vertebrate prey including lizards, juvenile birds, and small rodents. The massive Parson’s Chameleon can tackle relatively large prey items, while miniature species like Brookesia specialize in tiny invertebrates including mites, springtails, and fruit flies.

Hunting strategy combines patience with explosive action. Chameleons typically employ a sit-and-wait approach, positioning themselves along branches or among foliage frequented by insects. Their cryptic coloration and motionless posture make them nearly invisible. When prey enters visual range, the chameleon fixates with both eyes to calculate distance precisely. The subsequent tongue strike represents one of nature’s fastest movements—the tongue accelerates from zero to maximum velocity in just milliseconds, striking prey before it can react.

The tongue itself is a biological masterpiece. Composed of specialized muscle wrapped around an accelerator apparatus, it can extend 1.5-2 times the chameleon’s body length. The tip features a muscular pad covered in thick mucus and possessing a subtle cupped shape that creates suction. Upon contact, both adhesion and suction secure the prey, which is then rapidly retracted into the mouth. High-speed photography reveals the entire process—launch, capture, and retraction—completes in approximately 0.07 seconds.

Feeding frequency depends on prey availability, season, and individual energy demands. Growing juveniles and gravid females require particularly high caloric intake. Most adult chameleons feed every 1-3 days under natural conditions, though they can survive extended periods without food if necessary.

Some species show surprising dietary flexibility. Certain large chameleons occasionally consume plant material including leaves, flowers, and fruit, though whether this provides significant nutrition or serves other purposes (hydration, mineral intake, digestive aid) remains debated. The Veiled Chameleon exhibits the most consistent plant consumption, possibly an adaptation to its semi-arid habitat where animal prey may be seasonally scarce.

Chameleons obtain most hydration from dew and raindrops on leaves, licking moisture from vegetation rather than drinking from puddles or streams. This behavior reflects their arboreal lifestyle where standing water is rare.

Predators and Threats

Despite their remarkable adaptations, chameleons face numerous predators and increasingly severe anthropogenic threats. Their slow movement and reliance on camouflage over speed make them vulnerable to predators that hunt by sight or scent.

Natural predators vary by habitat but commonly include birds of prey such as hawks, falcons, kestrels, and shrikes that pluck chameleons from exposed perches. Snakes pose perhaps the greatest threat—tree-dwelling species like boomslangs, vine snakes, and various colubrids actively hunt chameleons, while ground predators catch individuals during rare terrestrial movements. Mammals including civets, genets, monkeys, and larger carnivores opportunistically consume chameleons. Even other reptiles, particularly monitor lizards, prey on them.

At night, chameleons become especially vulnerable. Sleeping individuals maintain their grip but cannot flee or defend effectively, making them easy targets for nocturnal predators. Their pale sleeping coloration actually makes them more visible, though this may be unavoidable given thermoregulatory constraints.

Parasites and diseases also affect wild populations, though less visibly than predation. Various mites, ticks, and internal parasites can weaken individuals, while fungal and bacterial infections pose risks, particularly in unusually wet conditions.

However, anthropogenic threats dwarf natural predation in impact. Habitat destruction represents the gravest danger—deforestation for agriculture, logging, and development eliminates chameleon habitat across their range. Madagascar has lost approximately 90% of its original forest cover, catastrophically impacting endemic chameleons. In Africa, expanding human populations drive agricultural conversion of forests and woodlands.

Climate change poses mounting concerns. Chameleons, as ectotherms dependent on specific temperature and humidity ranges, face direct physiological challenges from changing climatic conditions. Altered rainfall patterns, increased drought frequency, and rising temperatures may push species beyond their tolerance limits. Montane specialists face particularly acute risks as warming temperatures force range shifts upward until mountaintops provide no further refuge.

The international pet trade impacts certain species significantly. Popular species like Panther Chameleons, Veiled Chameleons, and Jackson’s Chameleons face collection pressure in some regions, though captive breeding now supplies much of the pet trade for these species. However, collection of rare and localized species continues, with newly discovered species sometimes appearing in trade before conservation assessments can be completed.

Pesticide use eliminates prey populations and may directly poison chameleons that consume contaminated insects. Agricultural intensification replacing diverse native vegetation with monocultures reduces habitat quality even where some trees remain.

Introduction of invasive species creates new threats. In some regions, invasive predators like rats prey on chameleons, while invasive plants alter habitat structure. Conversely, chameleons themselves become invasive when introduced outside native ranges—established populations of Jackson’s Chameleon in Hawaii and Florida demonstrate this, though impacts on native ecosystems remain under study.

Reproduction and Life Cycle

Chameleon reproduction showcases remarkable diversity in strategies and life history patterns. Most species are oviparous (egg-laying), though several montane African species have evolved viviparity (live birth)—an adaptation to cool highland environments where eggs might fail to develop.

Mating seasons typically align with optimal environmental conditions and prey availability, varying by region and species. In seasonal climates, breeding concentrates during specific periods, while equatorial species may breed year-round with individual females cycling through multiple reproductive attempts.

Courtship and mating involve elaborate rituals. Males display vibrant breeding colors—often the most brilliant coloration they can produce—while approaching females. If the female is receptive, she adopts submissive coloration and postures. Unreceptive females display rejection colors (often dark with contrasting spots or patterns) and may gape, hiss, rock aggressively, or even attack persistent males.

Copulation involves the male mounting the female from the side, with mating lasting from minutes to over an hour depending on species. Males possess hemipenes—paired reproductive organs, though only one is used during any given mating.

Following successful mating, egg-laying species undergo dramatic physical changes as eggs develop. Gravid females become noticeably swollen and often display distinctive gravid coloration. The gestation period varies tremendously: small species may carry eggs just 20-30 days, while large species like Parson’s Chameleon may carry them for 40-50 days before laying.

Oviposition requires suitable substrate. Females descend from trees (a vulnerable time) to dig nest chambers in soil, often choosing locations with appropriate temperature and moisture characteristics. Clutch sizes range from just 2-4 eggs in small species to over 80 in large species like the Veiled Chameleon, with most species producing 10-40 eggs. After depositing eggs, females carefully backfill and camouflage the nest, then abandon it—chameleons provide no parental care.

Incubation periods show astonishing variation. Some species hatch in 4-6 months under warm conditions, while others, particularly large Malagasy species, require 6-12 months or even longer. The eggs of Parson’s Chameleon hold the record, requiring 18-24 months to hatch—among the longest incubation periods of any reptile.

Viviparous species skip egg-laying, retaining developing young internally. Following a gestation period of 5-7 months, females give birth to live young encased in thin transparent membranes which they immediately break free from. Litter sizes in live-bearing species are typically smaller than clutch sizes in related egg-layers, ranging from 8-30 offspring.

Hatchlings emerge as miniature adults, fully formed and immediately independent. They typically measure 1-2 inches and face enormous predation pressure. Juvenile coloration often differs from adults, sometimes providing enhanced camouflage during this vulnerable period.

Growth rates depend on food availability and temperature. Most species reach sexual maturity within 6-12 months, though some large species require 18-24 months. In the wild, this rapid maturation makes sense given high mortality rates.

Lifespan varies considerably by species. Smaller species often live just 2-4 years, while medium-sized species typically survive 5-8 years, and large species may reach 10-15 years under optimal conditions. In captivity with controlled conditions and veterinary care, lifespans often exceed wild expectations.

Some species demonstrate semelparous tendencies—breeding once and dying shortly thereafter—though this isn’t absolute. Female Labord’s chameleons in Madagascar exhibit the most extreme pattern, with the entire adult population dying after a single breeding season, leaving only developing eggs to continue the species. This annual life cycle represents one of the shortest vertebrate lifespans.

Population

Chameleon conservation status ranges from stable to critically endangered, with significant variation among species. The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List provides assessments for most described species, though some recently discovered species await evaluation.

Overall population numbers remain challenging to estimate given chameleons’ cryptic nature and often inaccessible habitats. No reliable global population estimate exists aggregating all species. However, individual species assessments provide concerning insights.

Many widespread, adaptable species maintain healthy populations and are classified as Least Concern. These include the Flap-necked Chameleon across much of sub-Saharan Africa, the Common Chameleon in North Africa and southern Europe, and the Veiled Chameleon in the Arabian Peninsula. These species tolerate moderate habitat disturbance and persist in agricultural landscapes.

However, a troubling proportion of chameleons face conservation concerns. Numerous species are classified as Vulnerable, Endangered, or Critically Endangered. Madagascar’s chameleons face particularly severe threats—approximately 40% of assessed Malagasy species are threatened with extinction. Species with restricted ranges in isolated forest fragments face the highest risks.

Examples of critically endangered species include Chapman’s Pygmy Chameleon (Rhampholeon chapmanorum) from Malawi, restricted to a tiny forest fragment facing ongoing degradation. Tarzan’s Chameleon (Calumma tarzan) from Madagascar, described only in 2010, occupies a severely limited range already impacted by deforestation. The Belalanda Chameleon (Furcifer belalandaensis) from southern Madagascar teeters on extinction with perhaps fewer than 2,500 individuals remaining.

Population trends show concerning patterns. Species dependent on intact primary forests generally face declining populations as habitat loss accelerates. Deforestation rates in Madagascar, despite conservation efforts, continue eliminating habitat. African forest species similarly decline as expanding agriculture converts forests to cropland.

Some populations show stability or even increases where habitat protection succeeds. Protected areas harboring viable chameleon populations demonstrate conservation effectiveness. However, many threatened species occur partly or entirely outside protected areas, leaving populations vulnerable.

Certain species face additional pressures beyond habitat loss. Over-collection for the pet trade has impacted specific populations, though international trade regulations (CITES) now protect many species. Climate change emerges as an increasingly severe threat, particularly for montane specialists with narrow thermal tolerance ranges.

Conservation programs targeting chameleons include habitat protection through national parks and reserves, captive breeding programs for critically endangered species, community-based conservation initiatives engaging local populations in protection efforts, research programs monitoring population trends and ecology, and education campaigns raising awareness about chameleon conservation needs.

Several organizations focus specifically on reptile conservation, including Global Wildlife Conservation’s work on Madagascar reptiles and the IUCN SSC Chameleon Specialist Group coordinating research and conservation priorities worldwide.

Despite challenges, some success stories provide hope. Certain species once feared extinct have been rediscovered, and protected areas do sustain viable populations. Captive breeding programs have established insurance populations of some critically endangered species, potentially enabling future reintroduction efforts.

Conclusion

Chameleons stand as testament to evolution’s boundless creativity—ancient reptiles transformed through millions of years into the ultimate ambush predators of the arboreal world. From their ballistic tongues launching faster than jets to eyes that survey the world independently, from feet engineered as biological vise-grips to skin containing living color-shifting crystals, every aspect of chameleon biology inspires awe at nature’s engineering prowess.

Yet these remarkable creatures face an uncertain future. Habitat destruction, climate change, and human exploitation threaten to erase millions of years of evolutionary refinement within just decades. Madagascar’s forests fall at alarming rates, taking irreplaceable chameleon diversity with them. African species lose ground to agricultural expansion. Even adaptable generalist species may struggle as ecosystems unravel.

The chameleon’s story ultimately reflects our own choices. Will we preserve the forests these animals require? Will we act decisively on climate change before montane specialists lose their high-elevation refuges? Will we value biodiversity not just for utility but for the sheer wonder it represents?

Every chameleon species that vanishes erases a unique evolutionary experiment, a specific solution to survival’s challenges that can never be replicated. Their loss diminishes not just biodiversity but human experience—fewer children will witness their first chameleon’s color change, fewer scientists will unravel their biomechanical secrets, fewer artists will find inspiration in their otherworldly beauty.

Conservation requires action. Support organizations protecting critical habitats. Advocate for stronger environmental policies. Choose sustainable products that don’t drive deforestation. If captivated by these animals, ensure any kept as pets are captive-bred, not wild-caught. Share knowledge about chameleons with others—appreciation drives conservation.

The chameleon survived the extinction of dinosaurs, persisted through ice ages, and radiated across continents into dazzling diversity. With commitment and action, we can ensure they continue their ancient lineage into a future where humans and chameleons share a thriving, biodiverse planet. The choice, quite simply, is ours.