In the shadowy depths of Central European forests, beneath moss-covered logs and among the leaf litter of ancient woodlands, lives a creature that appears to have crawled straight from the pages of medieval folklore. The fire salamander, with its striking black body adorned with brilliant yellow markings, has captivated human imagination for millennia. Ancient Romans believed these amphibians were born from flames and could withstand fire—a myth so persistent that the salamander became a symbol of the element itself in alchemical traditions. While modern science has dispelled these supernatural associations, the fire salamander remains no less remarkable. This magnificent amphibian represents a living link to ancient evolutionary lineages, demonstrates extraordinary biological adaptations, and serves as a critical indicator of forest ecosystem health across Europe and parts of Asia.

Facts

- Fire salamanders can live for more than 20 years in the wild, with some captive individuals reaching over 50 years of age, making them among the longest-lived amphibians.

- Unlike most salamanders that lay eggs in water, many fire salamander populations give birth to live larvae, and some subspecies even give birth to fully metamorphosed juveniles.

- Their skin secretions contain potent alkaloid toxins called samandarin and samandarine, which can cause convulsions and hyperventilation in predators and were historically used in folk medicine.

- Fire salamanders exhibit remarkable site fidelity, often returning to the exact same hibernation spots year after year, sometimes traveling over 100 meters to reach their preferred locations.

- The distinctive yellow and black pattern is unique to each individual, functioning like a fingerprint that researchers can use to identify specific salamanders.

- They possess the ability to regenerate lost limbs and tail portions, though this capability diminishes with age.

- Fire salamanders are among the few amphibians that produce vocalizations, emitting faint squeaking sounds when threatened or during mating encounters.

Species

The fire salamander belongs to a well-defined taxonomic lineage that places it firmly within the amphibian world:

Kingdom: Animalia

Phylum: Chordata

Class: Amphibia

Order: Urodela (also called Caudata)

Family: Salamandridae

Genus: Salamandra

Species: Salamandra salamandra

The fire salamander exhibits remarkable diversity across its range, with taxonomists recognizing between 13 to 15 distinct subspecies, though classification remains somewhat debated among herpetologists. The most widely recognized subspecies include S. s. salamandra (the nominate subspecies found across much of Central Europe), S. s. terrestris (found in southwestern Europe with particularly vibrant coloration), S. s. gallaica (the Galician fire salamander with distinctive stripe patterns), and S. s. bernardezi (the endemic Asturian subspecies that gives birth to fully metamorphosed young rather than larvae).

The genus Salamandra also includes other species such as the Alpine salamander (Salamandra atra), which is entirely black and fully viviparous, and the critically endangered Corsican fire salamander (Salamandra corsica). These sister species share the fire salamander’s general body plan but have adapted to different ecological niches and reproductive strategies.

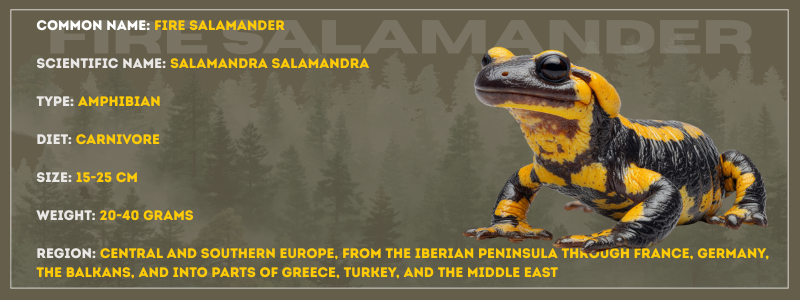

Appearance

The fire salamander is an unmistakably striking amphibian that commands attention with its bold warning coloration. Adults typically measure between 15 to 25 centimeters in total length, with females generally growing slightly larger than males. Some exceptional individuals, particularly in populations with abundant food sources, may reach lengths of up to 30 centimeters. Weight ranges from 20 to 40 grams for most adults, though larger specimens can exceed 50 grams.

The salamander’s most distinctive feature is its dramatic coloration pattern: a glossy black or dark brown background interrupted by brilliant yellow or orange markings. These markings can take various forms depending on the subspecies—some populations display irregular spots and blotches, while others show broad longitudinal stripes running from head to tail, and still others exhibit a combination of both patterns. The intensity of the yellow coloration can range from pale lemon to deep golden-orange, with some rare individuals displaying reddish hues.

The body is robust and cylindrical, with a distinctly flattened head featuring prominent parotoid glands behind the eyes—specialized structures that secrete the salamander’s toxic defensive compounds. Their eyes are large, dark, and slightly protruding, providing excellent vision in the low-light conditions of their forest floor habitat. The skin appears wet and glossy due to constant mucus secretion, which helps keep the salamander moist and provides additional chemical defense.

Four sturdy legs with well-developed toes (four on the front limbs, five on the hind limbs) enable the salamander to navigate complex forest terrain with surprising agility. The tail is roughly cylindrical and comprises about 40-50% of the total body length. Males can often be distinguished from females by their slightly more swollen cloacal region, particularly during the breeding season.

Behavior

Fire salamanders are predominantly nocturnal creatures that exhibit a cautious, deliberate lifestyle centered around moisture conservation and prey acquisition. During daylight hours, they remain hidden beneath logs, stones, in rock crevices, or within underground burrows, emerging only after dark or during rainy weather when humidity levels are high. Their activity patterns are strongly influenced by temperature and moisture, with peak activity occurring on warm, humid nights, particularly following rainfall.

These salamanders are largely solitary animals, though they may congregate in favorable microhabitats, particularly during hibernation or near breeding sites. They establish small home ranges, typically covering only a few hundred square meters, which they navigate using a combination of chemical cues and spatial memory. Research has demonstrated their remarkable homing ability—displaced salamanders can return to their original territories from distances exceeding 100 meters.

When threatened, fire salamanders employ a fascinating defensive behavior repertoire. Their primary defense is chemical: when molested, they secrete toxic alkaloids from glands distributed across their skin, with the most concentrated secretions coming from the parotoid glands. In extreme situations, they can actually spray these secretions up to 80 centimeters, aiming for the eyes and mouth of predators. This behavior is accompanied by a distinctive posture—the salamander arches its back, raises its tail, and positions its body to display the bright warning colors most effectively.

Fire salamanders move with a characteristic slow, deliberate gait, alternating diagonal limbs in a walking pattern that conserves energy. Despite their generally languid movements, they can execute surprisingly quick lunges when capturing prey. They communicate primarily through chemical signals, depositing pheromones that convey information about sex, reproductive status, and territory. The faint vocalizations they produce, while not well studied, appear to serve both defensive and social functions.

Intelligence in fire salamanders manifests in their ability to learn and remember complex spatial information, recognize individual conspecifics, and modify their behavior based on experience. Laboratory studies have shown they can be trained to associate certain stimuli with food rewards and can navigate mazes with increasing efficiency over time.

Evolution

The evolutionary history of fire salamanders extends deep into the amphibian lineage, providing a window into the ancient transition of vertebrate life from water to land. The order Urodela, to which fire salamanders belong, diverged from other amphibian lineages approximately 160 to 200 million years ago during the Jurassic period, making salamanders contemporaries of the dinosaurs.

The family Salamandridae, which includes fire salamanders, newts, and their relatives, likely originated in Eurasia during the Cretaceous period, roughly 100 million years ago. Fossil evidence for salamandrids remains relatively sparse due to the delicate nature of amphibian skeletons and their preference for forest habitats where fossilization is rare. However, fossils attributed to the genus Salamandra have been found in European deposits dating to the Miocene epoch, approximately 15-20 million years ago, suggesting the genus has maintained a relatively consistent body plan for millions of years.

The fire salamander’s evolutionary success can be attributed to several key adaptations. The development of potent skin toxins provided effective predator deterrence, allowing these slow-moving amphibians to adopt a conspicuous warning coloration rather than relying on camouflage or speed. The evolution of various reproductive strategies across different populations—from egg-laying to live birth to fully terrestrial development—demonstrates remarkable evolutionary flexibility in response to local environmental conditions.

The species likely underwent significant diversification during the Pleistocene glacial cycles of the past 2.6 million years. As ice sheets advanced and retreated across Europe, fire salamander populations became isolated in refugia—particularly in the Iberian Peninsula, Italy, and the Balkans. This geographic isolation promoted genetic divergence and the evolution of the distinct subspecies we recognize today. As glaciers receded, some populations expanded northward, while others remained isolated in mountainous regions, creating the complex distribution pattern observed in modern times.

Molecular studies suggest that fire salamanders share a relatively recent common ancestor with Alpine salamanders, with the two lineages diverging perhaps 10-15 million years ago. This relationship highlights how different evolutionary pressures—the fire salamander adapting to lowland deciduous forests and the Alpine salamander conquering high-elevation environments—can drive dramatic differences in ecology and reproductive biology from closely related ancestral stock.

Habitat

Fire salamanders inhabit a distinctive ecological niche across much of Central and Southern Europe, with their range extending from the Iberian Peninsula in the west through France, Germany, and the Balkans, reaching into parts of Greece, Turkey, and even into the Middle East in isolated populations. They are notably absent from the British Isles, Scandinavia, and most of Eastern Europe, with their distribution closely following the extent of suitable deciduous and mixed forest habitats.

These amphibians show a strong preference for hilly and mountainous terrain, typically occurring at elevations ranging from sea level to approximately 2,000 meters, though most populations thrive between 200 and 1,000 meters elevation. They are quintessentially creatures of the forest floor, requiring mature deciduous or mixed woodlands with specific microhabitat features essential for their survival.

The ideal fire salamander habitat consists of old-growth or mature secondary forests dominated by trees such as beech, oak, chestnut, and maple. These forests must provide three critical features: abundant ground cover in the form of leaf litter, rotting logs, stones, and root systems that create humid microhabitats; proximity to clean, cool, permanent or semi-permanent water sources such as streams, springs, or seepage areas for larval development; and structural complexity with various shelter sites for different life stages and seasons.

The forest floor microclimate is crucial—fire salamanders require consistently high humidity levels and moderate temperatures. They avoid both excessively dry conditions and direct sunlight, which can be rapidly lethal due to their permeable skin and limited ability to regulate body temperature. The thick canopy of mature forests creates the cool, moist conditions they need, while the accumulation of coarse woody debris and leaf litter provides countless hiding spots and hunting grounds.

Water quality is particularly important for reproductive success. Fire salamander larvae develop in cold, clean, well-oxygenated streams and pools, typically with rocky or gravelly bottoms and moderate current. These breeding sites are usually small headwater streams, springs, or natural forest pools that maintain water levels throughout the larval development period of 3-5 months.

Seasonal habitat use varies considerably. During the active season from spring through autumn, salamanders may be found throughout suitable forest areas. As temperatures drop in late autumn, they migrate to hibernation sites—typically underground cavities, deep rock fissures, or abandoned rodent burrows that provide protection from freezing temperatures. These hibernacula may be shared by multiple individuals, with some sites being used consistently across generations.

Diet

Fire salamanders are opportunistic carnivores with a diet that reflects their role as important predators of forest floor invertebrate communities. Their feeding strategy is characterized by a sit-and-wait approach combined with slow, methodical hunting as they patrol their territories during humid nights.

The bulk of the fire salamander’s diet consists of terrestrial invertebrates, with prey selection largely determined by size, availability, and the salamander’s gape limitation. Adult fire salamanders primarily consume earthworms, which constitute a substantial portion of their diet due to their abundance in moist forest soils and high nutritional value. Slugs and snails form another major dietary component, particularly during wet conditions when these mollusks are most active. The salamander’s powerful jaws and numerous small teeth are well-adapted to grasping and consuming these soft-bodied prey items.

Insects and their larvae represent a diverse category of prey, including ground beetles, crickets, grasshoppers, caterpillars, and various beetle larvae found in rotting wood and leaf litter. Spiders, millipedes, centipedes, and sowbugs (woodlice) are also regularly consumed. During peak abundance periods, such as spring when many invertebrates are breeding, fire salamanders can be highly selective, preferring larger, more nutritious prey items over smaller ones.

The hunting technique employed by fire salamanders relies heavily on visual and chemical detection. They possess excellent vision adapted to low-light conditions, allowing them to detect prey movement in the dim forest understory. Once prey is detected within striking range—typically just a few centimeters—the salamander executes a rapid lunge, opening its mouth and using its sticky tongue to capture the prey item. Larger prey may be grasped with the jaws and manipulated using the forelimbs before being swallowed whole.

Feeding rates vary considerably with temperature, season, and individual condition. During the active season, adult fire salamanders may feed several times per week, though they can survive extended periods without food, relying on fat reserves. Gravid females are particularly voracious feeders, needing to accumulate sufficient energy reserves for larval development.

Larvae, developing in aquatic environments, have a markedly different diet consisting of aquatic invertebrates such as insect larvae (especially caddisfly, mayfly, and midge larvae), small crustaceans, and worms. Larval fire salamanders are active predators that hunt by sight, snapping at any appropriately sized moving object.

Predators and Threats

Despite their potent chemical defenses, fire salamanders face predation pressure from a select group of animals that have evolved tolerance or behavioral strategies to overcome their toxicity. Natural predators are relatively few, but those that do prey on fire salamanders can have significant local impacts on populations.

Among avian predators, certain species of birds, particularly corvids such as crows and ravens, have learned to avoid the toxic skin while accessing the less-toxic muscle tissue. They may kill salamanders and consume only specific body parts or wipe the salamander against substrate to remove toxic secretions before consumption. Some raptors, including owls and buzzards, occasionally take fire salamanders, though this is not a preferred prey item.

Mammalian predators include red foxes, badgers, and wild boars, though predation rates are generally low. Some snake species, particularly grass snakes, demonstrate tolerance to salamander toxins and actively hunt them. In aquatic environments, fire salamander larvae face predation from a wider array of threats including dragonfly larvae, diving beetles, fish (where they coexist), and even adult salamanders of other species.

Anthropogenic threats represent far more significant dangers to fire salamander populations than natural predation. Habitat loss and fragmentation through deforestation, agricultural expansion, and urban development have eliminated or degraded vast swaths of suitable habitat. The conversion of mixed and deciduous forests to coniferous monocultures particularly impacts salamanders, as these plantations lack the structural complexity and moisture retention of natural forests.

Climate change poses an increasingly serious threat, as rising temperatures and altered precipitation patterns affect the cool, moist microhabitats fire salamanders require. Droughts can eliminate breeding sites, desiccate forest floor habitats, and extend periods when salamanders cannot be active. Extreme weather events may also directly kill individuals or destroy hibernacula.

Road mortality during migration to breeding sites or between seasonal habitats kills substantial numbers of salamanders annually. In some fragmented populations, roads represent significant barriers to gene flow and can isolate small populations vulnerable to local extinction.

Perhaps the most devastating recent threat is the emergence of Batrachochytrium salamandrivorans (Bsal), a deadly fungal pathogen first identified in 2013. This chytrid fungus causes severe skin lesions and has resulted in catastrophic population declines and local extinctions in parts of the Netherlands, Belgium, and Germany, with mortality rates exceeding 90% in affected populations. The rapid spread of Bsal through both wild and captive amphibian populations represents an existential threat to fire salamanders across their range, and intensive research and conservation efforts are underway to understand and combat this disease.

Water pollution from agricultural runoff, acid rain, and industrial contaminants affects both adult habitat quality and, critically, the clean water required for successful larval development. Collection for the pet trade, while less significant than in past decades, continues in some regions.

Reproduction and Life Cycle

Fire salamanders exhibit a remarkable and somewhat unusual reproductive strategy among amphibians, characterized by internal fertilization, lengthy embryonic development within the female’s body, and the birth of live larvae—a reproductive mode called ovo-viviparity.

The reproductive cycle begins in late spring or summer when males and females encounter each other during their nocturnal activities. Courtship is a relatively brief affair compared to many other salamander species. The male approaches a receptive female and performs a nuptial dance, rubbing his chin along her body while attempting to position himself beneath her. If the female is receptive, the male deposits a spermatophore—a gelatinous capsule containing sperm—on the substrate, which the female then picks up with her cloaca, allowing internal fertilization to occur.

Following successful mating, females retain the fertilized eggs within their oviducts throughout the remainder of the summer, autumn, and winter. This extended gestation period typically lasts 8-10 months, though it can vary from 6 to 12 months depending on temperature, elevation, and individual variation. During this time, embryos develop within their egg membranes, nourished by yolk reserves, while the female provides a protected environment and may provide additional nutrition through uterine secretions.

Birth typically occurs in late winter or spring, when females migrate to suitable aquatic habitats—cool, clean streams, springs, or forest pools. The female partially submerges herself in shallow water and gives birth to anywhere from 10 to 70 larvae, though 20-40 is typical. The larvae emerge still enclosed in egg membranes but quickly wriggle free to begin their aquatic phase.

Remarkably, some subspecies, particularly S. s. bernardezi and S. s. fastuosa found in mountainous regions of Spain, exhibit full viviparity—they give birth to fully metamorphosed juveniles rather than larvae. In these populations, one or two embryos develop to advanced stages by consuming their siblings within the oviduct (a process called adelphophagy), eventually being born as miniature adults measuring 5-6 centimeters.

Newly deposited larvae are typically 25-35 millimeters in length, with external gills, a laterally compressed tail with a prominent fin, and four limbs. They are dark brown or black with yellowish markings. The larval period lasts approximately 3-5 months, during which they grow to 60-80 millimeters while feeding voraciously on aquatic invertebrates.

Metamorphosis involves the reabsorption of external gills, modification of the tail, development of eyelids, and changes in skin structure. Newly metamorphosed juveniles emerge from water in late summer or autumn at sizes of 5-7 centimeters. They retain the basic black-and-yellow coloration pattern but are generally duller than adults, with colors intensifying as they mature.

Sexual maturity is reached relatively late compared to many amphibians—typically between 3-4 years of age, though this varies with population, food availability, and climate. Some individuals in harsh environments may not reach maturity until 5-6 years of age.

Fire salamanders exhibit impressive longevity for amphibians. In the wild, individuals regularly survive 20-25 years, with some populations showing evidence of individuals exceeding 30 years. In captivity, with optimal conditions and freedom from predation and disease, fire salamanders have lived over 50 years, making them among the longest-lived amphibian species.

Population

The fire salamander is currently classified as “Least Concern” on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, reflecting its relatively wide distribution across Europe and stable populations in many regions. However, this overall classification masks considerable variation in population status across the species’ range, with some subspecies and regional populations facing severe threats.

Estimating precise global population numbers for fire salamanders is extremely challenging due to their secretive, nocturnal habits and patchy distribution. Population density studies in optimal habitats have recorded anywhere from 50 to over 1,000 individuals per hectare, though such high densities are exceptional and localized. More typical densities in good-quality habitat range from 100-300 individuals per hectare. Extrapolating from habitat availability and local density estimates, the total European population likely numbers in the millions, though this figure carries substantial uncertainty.

Population trends vary significantly by region. In much of Central Europe, including Germany, France, Switzerland, and Austria, populations appear relatively stable where suitable habitat persists, though many populations show evidence of fragmentation and isolation. In Southern Europe, particularly in Spain and Portugal, some subspecies maintain healthy populations in mountainous regions, while lowland populations have declined.

The most alarming population trend concerns the impact of Bsal fungal disease. Since its identification in 2013, this pathogen has caused catastrophic declines in affected regions. The Netherlands experienced population crashes of over 96% in some areas, with entire local populations extirpated. Similar devastating impacts have been documented in Belgium and parts of Germany. Conservative estimates suggest tens of thousands of fire salamanders have died from Bsal, with the disease continuing to spread through susceptible populations.

Several subspecies warrant particular conservation concern. The Galician fire salamander (S. s. gallaica) and the Asturian fire salamander (S. s. bernardezi) have restricted ranges and specialized habitat requirements that make them particularly vulnerable to climate change and habitat loss. Some isolated populations in Greece and the Balkans are genetically distinct and of high conservation value but face threats from habitat degradation and small population sizes.

Long-term monitoring programs in countries like Germany and Switzerland indicate that while some populations remain robust, there is an overall pattern of slow decline and increasing fragmentation, particularly in lowland areas subject to intensive agriculture and urbanization. Populations in protected areas, such as national parks and nature reserves, generally show more stable trends.

Climate change modeling suggests that fire salamanders may face significant range contractions in coming decades, particularly at the southern and low-elevation edges of their distribution, as temperatures rise and drought frequency increases. However, some predictions indicate potential range expansions at northern latitudes and higher elevations if suitable habitat exists.

Conclusion

The fire salamander stands as both an ancient survivor and a modern indicator of forest ecosystem health. From its evolutionary origins in the age of dinosaurs to its current status navigating an increasingly human-dominated landscape, this remarkable amphibian embodies the resilience and vulnerability of European wildlife. Its brilliant warning colors remind us that nature’s most striking beauty often serves vital survival functions, while its complex life cycle—bridging terrestrial and aquatic worlds—highlights the intricate ecological connections that sustain biodiversity.

Yet the fire salamander’s future remains uncertain. The emergence of deadly fungal pathogens, the relentless fragmentation of forest habitats, and the accelerating impacts of climate change present formidable challenges that threaten to silence the ancient lineage this species represents. Every fire salamander that successfully navigates the perils of its environment, returns to its ancestral breeding pool, and gives birth to a new generation is a small victory against these mounting threats. As we move forward, the fate of the fire salamander will reflect our broader commitment to preserving the wild spaces and ecological processes that have shaped life on Earth for millions of years. Protecting these magnificent amphibians means protecting the forest ecosystems they inhabit—a legacy worth preserving for the countless species, including ourselves, that depend on healthy, functioning natural systems.