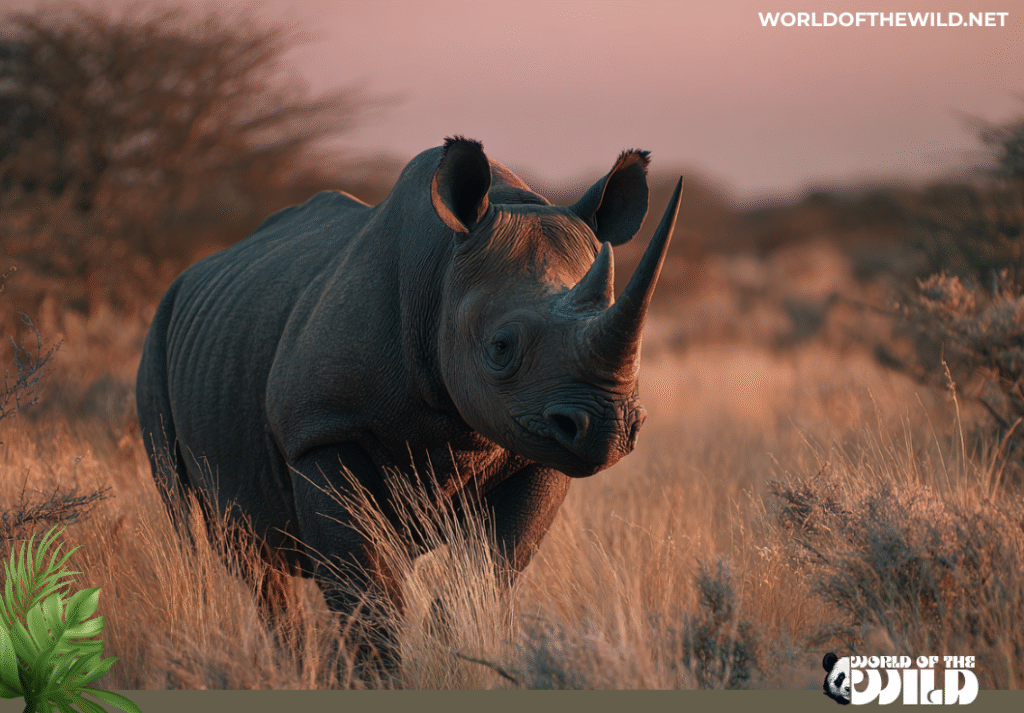

Imagine a prehistoric titan, a living relic of a time before recorded history, moving silently through the dense African bush. This is the Black Rhino (Diceros bicornis), a magnificent animal whose very existence is a testament to the resilience of nature. Yet, this great beast is also a profound symbol of our ongoing global conservation crisis.

The Black Rhino is not merely fascinating for its sheer power and intimidating appearance, but its significance lies in its ecological role as a megaherbivore that shapes the savanna landscape, and in its precarious status as a species teetering on the brink. Its story is one of dramatic decline, desperate recovery efforts, and an urgent call to action.

Facts

Here are a few quick, compelling, and lesser-known facts about the Shadow Runner:

- Not Black: Despite its name, the Black Rhino is actually a dark grey or brownish-yellow. The name was likely used to distinguish it from the lighter-colored White Rhino.

- A “Hook-Lipped” Grazer: Its scientific name, bicornis, refers to its two horns, but its common name in some places is the “hook-lipped rhino” due to its prehensile, pointed upper lip, which is perfect for grasping leaves and twigs.

- Rapid Runners: Don’t let their size fool you! Black Rhinos can reach impressive speeds of up to 55 km/h (34 mph) in short bursts.

- Poor Eyesight, Great Smell: They have notoriously poor vision, often failing to recognize a stationary human from 30 meters away. However, they compensate with an extraordinary sense of smell and hearing.

- Dung Piles are “Social Media”: Rhinos communicate extensively through piles of dung, called middens. By sniffing the middens, they can gather information about other rhinos’ age, sex, and reproductive status.

Species

The Black Rhino is classified within the domain of life as follows:

| Classification Rank | Group |

| Kingdom | Animalia |

| Phylum | Chordata |

| Class | Mammalia |

| Order | Perissodactyla (Odd-toed ungulates) |

| Family | Rhinocerotidae (Rhinos) |

| Genus | Diceros |

| Species | Diceros bicornis |

The Black Rhino is one of five living rhinoceros species. The others are the White Rhino, the Indian Rhino, the Javan Rhino, and the Sumatran Rhino.

Within the Black Rhino species itself, there were historically seven or eight recognized subspecies, though three are currently declared extinct:

- Eastern Black Rhino (D. b. michaeli)

- South-Central Black Rhino (D. b. minor)

- South-Western Black Rhino (D. b. occidentalis)

- Western Black Rhino (D. b. longipes) (Declared Extinct)

Appearance

The Black Rhino is a large, powerful animal, built for pushing through dense vegetation.

- Size and Weight: They are smaller and lighter than the White Rhino, but still massive. Adults stand about 1.4 to 1.8 meters (4.6 to 5.9 feet) tall at the shoulder and can weigh between 800 and 1,400 kg (1,760 to 3,090 lbs).

- Color: As mentioned, their skin is a dark grey or brownish-grey, often taking on the color of the local soil they wallow in, which acts as natural insect repellent and sunscreen.

- Distinctive Features: The most notable features are their two horns. The front horn is typically longer than the back, averaging around 50 cm (20 in), though lengths over a meter have been recorded. Unlike the White Rhino, the Black Rhino has a pointed, prehensile upper lip—a key distinguishing feature—used like a finger to browse on woody plants. They also have a relatively smaller head and a more curved back profile compared to the White Rhino.

Behavior

Black Rhinos are generally considered solitary creatures, preferring to roam independently, except for mothers with their calves.

- Daily Routine: Their days are spent feeding in the early morning and late afternoon, often resting or wallowing in the shade or mud during the hottest parts of the day. Mud wallowing is essential for cooling down and protecting their skin from parasites.

- Communication: They use a variety of snorts, bellows, and grunts. Their most critical communication method, however, is scent marking. They use urine spraying and, as noted above, meticulously placed piles of dung (middens) to advertise their presence and mark their home range.

- Unique Adaptation (The Lip): Their prehensile upper lip is a remarkable adaptation. While the White Rhino has a broad, square lip for grazing grass, the Black Rhino uses its pointed lip to grasp and pull leaves, shoots, and fruit from high branches, making it a specialized browser.

Evolution

The Rhinocerotidae family has a deep and ancient evolutionary history, tracing back tens of millions of years.

The ancestors of modern rhinos first appeared in Eurasia during the Eocene epoch, around 40-50 million years ago. The lineage that led to the African rhinos, Diceros (Black Rhino) and Ceratotherium (White Rhino), diverged from the Asian species a long time ago.

The genus Diceros is believed to have appeared in Africa during the Pliocene epoch, approximately 5 million years ago. The Black Rhino specifically represents a more ancient, primitive lineage compared to the White Rhino. Its browsing specialization is thought to reflect a more ancestral feeding strategy compared to the widespread grazing that the White Rhino adopted as grasslands expanded. The Black Rhino has largely maintained its original morphology, representing a successful, though now threatened, branch of the megafauna that once dominated the continent.

Habitat

The Black Rhino’s historical distribution was vast, encompassing much of sub-Saharan Africa. Today, its range is highly fragmented.

- Geographic Range: Current populations are found primarily in Eastern and Southern Africa, including countries like Kenya, Tanzania, Namibia, Zimbabwe, and South Africa.

- Specific Environment: They are adaptable but prefer environments that offer a good balance of cover and food. This includes savannas, dense thickets, shrublands, and open grasslands with access to woody browse and water sources. They are particularly fond of areas with dense, thorny vegetation that provides shelter and protection, which is also where their darker coloration offers excellent camouflage.

Diet

The Black Rhino is a herbivore, exclusively eating plant matter.

- Primary Food Sources: It is a browser, not a grazer. Its diet consists mainly of:

- Leaves and Shoots

- Twigs and Branches

- Thorny Bushes and Shrubs

- Fruit and Seed Pods

- Foraging: They are selective feeders, using their specialized prehensile lip to carefully select and pull specific parts of plants. They will browse on over 200 different plant species. They require constant access to water and will drink daily, though they can survive for a few days without it in arid conditions.

Predators and Threats

While adult Black Rhinos are virtually immune to natural predators, they face devastating human-caused threats.

- Natural Predators: Adult Black Rhinos have no significant natural predators due to their size, thick skin, and formidable horns. Lion prides or large groups of hyenas may occasionally attempt to take a very young calf, but the mother is fiercely protective.

- Anthropogenic Threats: The primary threats are entirely human-driven:

- Poaching: This is the single greatest threat. Rhinos are poached for their horns, which are tragically valued in traditional medicine and as status symbols in some Asian countries, despite being composed entirely of keratin (the same protein found in human hair and nails).

- Habitat Loss: The expansion of human settlements and agriculture has fragmented the rhino’s historical range, isolating populations and reducing genetic diversity.

Reproduction and Life Cycle

The Black Rhino has a slow reproductive rate, which makes population recovery difficult.

- Mating Rituals: Courtship can be an intense, prolonged, and sometimes aggressive process. Females typically reach sexual maturity around 4–7 years, while males mature later, around 7–10 years.

- Gestation Period: The mother carries the calf for an incredibly long 15 to 16 months.

- Offspring and Parental Care: They typically give birth to a single calf, which is highly dependent on the mother. The calf remains with its mother for up to three years, learning crucial survival skills and protection, before she is ready to mate again. This long interval between births is a major constraint on population growth.

- Lifespan: Black Rhinos can live for 30 to 40 years in the wild.

Population

The Black Rhino’s history is a stark lesson in overexploitation, followed by hard-won recovery.

- Conservation Status: Critically Endangered (CR).

- Global Population Estimate: Due to intensive, costly conservation efforts and anti-poaching patrols, the population has slowly recovered from its historic low. Current estimates (as of 2022) suggest there are approximately 6,195 Black Rhinos in the wild.

- Population Trends: The species suffered a catastrophic decline of 98% between 1960 and 1995 due to widespread poaching. While still critically endangered, the population has been steadily increasing since the mid-1990s, offering a glimmer of hope that dedicated conservation can work.

Conclusion

The Black Rhino is a majestic symbol of Africa’s wilderness and a powerful reminder of our responsibility as stewards of this planet. Its pointed lip, built for browsing the thorny acacia, and its powerful stance speak of millions of years of successful evolution.

Yet, this awe-inspiring creature is now defined by the single horn that has made it a target. The fight to save the Black Rhino is a fight against greed and ignorance, a battle waged daily by dedicated rangers on the front lines of conservation. Every Black Rhino calf born is a triumph. We have brought this ancient beast back from the very edge of extinction, but the threat remains. Their survival depends on the persistence of anti-poaching efforts, the protection of their remaining habitats, and the continued global commitment to zero tolerance for the illegal wildlife trade. The Shadow Runner must be allowed to run free, forever.