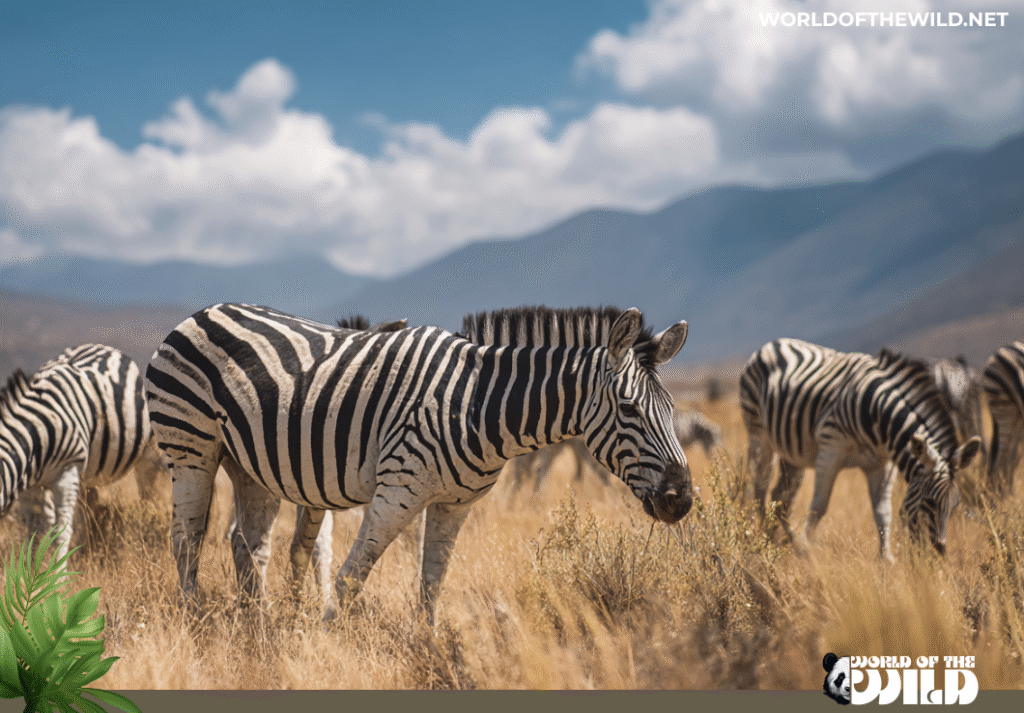

Few animals capture the imagination quite like the zebra. With their bold black-and-white stripes rippling across the African savanna, these magnificent equines seem almost too striking to be real—like horses painted by an artist who favored dramatic contrasts. Yet zebras are not only real but have thrived for millions of years across the African continent, their distinctive coats serving purposes far more sophisticated than simple aesthetics. These social, intelligent creatures represent one of nature’s most successful experiments in camouflage, thermoregulation, and predator confusion. From their complex herd dynamics to their surprisingly aggressive temperament, zebras continue to fascinate scientists and wildlife enthusiasts alike, reminding us that even the most familiar animals harbor remarkable secrets beneath their recognizable exteriors.

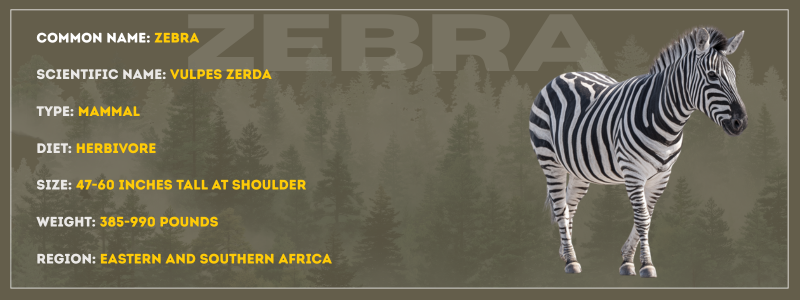

Facts

- No Two Zebras Are Alike: Each zebra’s stripe pattern is as unique as a human fingerprint, allowing researchers and herd members to identify individuals.

- Stripes May Confuse Flies: Recent research suggests zebra stripes deter biting flies, which have difficulty landing on striped surfaces due to visual confusion.

- They Can’t Be Truly Domesticated: Unlike horses, zebras have proven nearly impossible to domesticate due to their unpredictable nature, strong fight response, and excellent peripheral vision that makes them wary of capture.

- Powerful Kicks Can Kill Lions: A zebra’s kick can deliver over 1,300 pounds of force—enough to break a predator’s jaw or even kill a lion.

- Stripes May Act as Natural Air Conditioning: The differential heating of black and white stripes creates micro air currents that help cool the zebra’s body in the African heat.

- Newborn Foals Can Run Within an Hour: Baby zebras must be able to keep up with the herd almost immediately after birth to survive predator-rich environments.

- They Communicate Through Facial Expressions: Zebras use their ears, eyes, and mouths to convey emotions and intentions, with ear position being particularly communicative.

Species

Classification:

- Kingdom: Animalia

- Phylum: Chordata

- Class: Mammalia

- Order: Perissodactyla

- Family: Equidae

- Genus: Equus

- Species: Three distinct species exist

The genus Equus contains three living species of zebras, each adapted to different ecological niches across Africa. The Plains Zebra (Equus quagga) is the most common and widespread, with six recognized subspecies including Grant’s zebra and the now-extinct quagga, which was hunted to extinction in the 1880s. The Mountain Zebra (Equus zebra) includes two subspecies—the Cape mountain zebra and Hartmann’s mountain zebra—both adapted to rugged, mountainous terrain. Finally, the Grevy’s Zebra (Equus grevyi) is the largest and most endangered species, distinguished by its narrower stripes and massive rounded ears. Despite sharing the iconic striped pattern, these species differ significantly in size, stripe width, social structure, and habitat preferences, having evolved separately for approximately two million years.

Appearance

Zebras are stocky, muscular equines built for both speed and endurance. Plains zebras typically stand 47-55 inches tall at the shoulder and weigh between 385-850 pounds, while the larger Grevy’s zebra can reach 60 inches in height and weigh up to 990 pounds. Mountain zebras fall somewhere in between, with a more compact, athletic build suited for navigating rocky terrain.

The zebra’s most striking feature is, of course, its stripe pattern. While we typically think of zebras as black with white stripes, they’re actually dark-skinned animals with both black and white hair. The stripes extend across the entire body, including the mane, and each species displays distinct patterning. Plains zebras have broad stripes that wrap around the body and sometimes feature lighter “shadow stripes” between the main black stripes. Mountain zebras have vertical stripes on the neck and torso that meet horizontal stripes on the hindquarters, creating a distinctive grid pattern, along with a dewlap under the throat. Grevy’s zebras sport the thinnest, most numerous stripes, which are particularly narrow on the face and legs, giving them an almost etched appearance.

Beyond stripes, zebras possess strong, well-muscled necks topped with an erect mane of short, stiff hair. Their heads are large with prominent eyes positioned for excellent peripheral vision, and their ears are rounded and mobile, constantly scanning for danger. They have sturdy, single-hooved feet perfectly adapted for running on hard ground, and a tufted tail used for swatting flies and signaling to other herd members.

Behavior

Zebras are highly social animals with complex herd structures that vary by species. Plains and mountain zebras live in stable family groups called harems, consisting of one dominant stallion, several mares, and their offspring. These bonds are remarkably strong, with females often remaining together for life. Young males who leave or are driven from their birth groups form bachelor herds until they’re strong enough to establish their own harems. Grevy’s zebras, in contrast, maintain a more fluid social structure, with territorial males defending resource-rich areas while females and non-territorial males move freely between territories.

Communication among zebras is sophisticated and multi-modal. They produce various vocalizations, from loud braying calls that can carry over long distances to softer snorts and whinnies used for close-range interaction. Body language plays an equally important role—ear position indicates mood and intention, while showing teeth signals aggression or submission depending on context. Mutual grooming strengthens social bonds and serves the practical purpose of removing parasites from hard-to-reach places.

When threatened, zebras employ several defensive strategies. Their first response is typically flight, as they can reach speeds of up to 40 miles per hour and maintain a gallop for considerable distances. If cornered, however, they become fierce fighters, using powerful kicks and bites to defend themselves or their young. Stallions in particular are remarkably aggressive and will confront predators to protect their harem. The herd also employs a “confusion” defense—when running from predators, the mass of moving stripes makes it difficult for predators to single out individual targets.

Zebras are primarily diurnal, spending much of their day grazing and moving to water sources. They’re surprisingly intelligent, capable of recognizing individual humans and other zebras, learning complex navigation routes, and displaying problem-solving abilities. Their wariness and strong flight response, combined with excellent memory for threatening situations, contributed to their resistance to domestication.

Evolution

Zebras belong to the family Equidae, which originated in North America approximately 55 million years ago during the Eocene epoch. The earliest horse ancestors, like the fox-sized Hyracotherium (formerly called Eohippus), were forest-dwelling browsers that gradually evolved as grasslands expanded and forests receded.

The lineage that would lead to zebras crossed the Bering land bridge into Asia and eventually Africa around 2-3 million years ago during the Pliocene and Pleistocene epochs. Once in Africa, these equids underwent rapid diversification, adapting to the continent’s varied landscapes and ecological niches. The zebra’s distinctive stripes likely evolved during this period, though the exact timing remains debated among scientists.

Fossil evidence suggests that several now-extinct zebra species once roamed Africa, including the quagga, which survived until human hunting drove it to extinction. The quagga, a subspecies of the plains zebra, had stripes only on the front half of its body and represented an interesting evolutionary variation on the striped theme. Its extinction demonstrated the vulnerability of even relatively abundant species to human pressure.

Modern zebras share a common ancestor with horses and donkeys, diverging approximately 4-4.5 million years ago. DNA analysis reveals that Grevy’s zebra split off first, followed by the divergence between mountain and plains zebras around two million years ago. This evolutionary history reflects adaptation to different African environments—from the arid scrublands favored by Grevy’s zebra to the mountainous terrain of mountain zebras and the vast grasslands inhabited by plains zebras.

The evolution of zebra stripes has fascinated scientists for over a century. Recent research suggests multiple selective pressures contributed to this distinctive feature, including thermoregulation, visual confusion for predators, social recognition, and—most compellingly—protection against biting flies that spread diseases like African horse sickness.

Habitat

Zebras inhabit a variety of environments across eastern and southern Africa, with each species occupying distinct ecological zones. Their collective range extends from South Sudan and southern Ethiopia down to southern Africa, though their distribution is patchy and influenced by water availability, vegetation, and human land use.

Plains zebras occupy the most extensive range, thriving in grassland savannas, woodland savannas, and open plains from sea level to 14,000 feet in elevation. They prefer areas with short to medium-length grasses and require regular access to water, typically drinking daily or at least every few days. These zebras follow seasonal migration patterns, sometimes traveling hundreds of miles between wet and dry season ranges. They’re particularly abundant in protected areas like Tanzania’s Serengeti National Park, Kenya’s Masai Mara, and Botswana’s Okavango Delta.

Mountain zebras, as their name suggests, inhabit rugged, mountainous terrain and escarpments in southwestern Africa. They’re found in the mountain ranges of South Africa, Namibia, and Angola, typically at elevations between 3,300 and 6,600 feet. These environments feature steep, rocky slopes with sparse vegetation, and mountain zebras have developed impressive climbing abilities and sure-footedness to navigate this challenging terrain. Unlike their plains cousins, they can survive for several days without water, obtaining moisture from the vegetation they consume.

Grevy’s zebras occupy the most arid habitats, found in the semi-arid scrublands and grasslands of northern Kenya and southern Ethiopia. These areas receive minimal rainfall and feature sparse vegetation, requiring Grevy’s zebras to range widely in search of suitable forage. They’re particularly associated with the arid lands east of the Great Rift Valley, where they coexist with other drought-adapted species like gerenuk and oryx.

All zebra species require open or semi-open habitats that allow them to spot predators from a distance. They avoid dense forests and true deserts, needing a balance between adequate grazing opportunities and visibility for predator detection. Human agricultural expansion, fencing, and settlements have increasingly fragmented zebra habitats, disrupting migration routes and limiting access to historical grazing and water sources.

Diet

Zebras are obligate herbivores, specializing in grasses that form the bulk of their diet. As hindgut fermenters, they possess a relatively simple digestive system compared to ruminants like antelope, which means they must consume large quantities of food—up to 5% of their body weight daily—to meet their nutritional needs.

Plains zebras are primarily grazers, preferring fresh, green grasses but capable of eating coarser, drier vegetation when necessary. They often act as “pioneer grazers,” being among the first herbivores to enter an area of tall grass. Their feeding removes the tough upper stems, making the more nutritious lower growth accessible to smaller, more selective grazers like Thomson’s gazelles. This creates an ecological cascade that benefits multiple species. Plains zebras feed on a variety of grass species, adapting their diet seasonally based on availability.

Mountain zebras face more challenging foraging conditions in their rocky habitats. They consume a wider variety of vegetation, including various grass species, leaves, bark, and buds. During dry seasons, they may dig for roots and corms, and they’re known to strip bark from trees when other food is scarce. Their ability to extract nutrition from poor-quality forage helps them survive in environments where other herbivores might struggle.

Grevy’s zebras are the most adaptable feeders, consuming both grasses and browse. In their arid environment, they often feed on tough, fibrous grasses that cattle and other livestock refuse. They also eat leaves from shrubs and trees, particularly during dry periods. Their efficient digestive system and ability to derive nutrition from low-quality forage represent crucial adaptations to their harsh environment.

All zebras spend 60-80% of their day grazing and must drink regularly when water is available, though mountain and Grevy’s zebras can survive longer without water than plains zebras. They typically drink in the early morning or evening, approaching water sources cautiously due to predation risk. Their broad incisor teeth are perfect for clipping grass, while their powerful molars grind the tough vegetation before it enters their fermentation-based digestive system.

Predators and Threats

Zebras face predation throughout their lives, with different predators targeting different age classes. Lions are the primary predators of adult zebras, hunting them cooperatively in prides. A single lion may struggle to bring down a healthy adult zebra due to their aggressive defense, but coordinated pride attacks often succeed, particularly when targeting young, old, or injured individuals. Spotted hyenas also hunt zebras, either scavenging lion kills or conducting their own hunts using their remarkable endurance to run prey to exhaustion. Leopards occasionally take young or small zebras, while African wild dogs may target zebras when their preferred prey is scarce.

Nile crocodiles pose a significant threat at water sources, ambushing zebras when they come to drink. Young foals face additional predators, including cheetahs, caracals, and even large eagles like the martial eagle. Despite this predation pressure, healthy adult zebras in groups are formidable opponents, and predators typically seek out vulnerable individuals rather than confronting the herd.

Anthropogenic threats now pose far greater dangers to zebra populations than natural predation. Habitat loss and fragmentation represent the most significant challenge, as human settlements, agriculture, and livestock grazing consume zebra range. Fencing disrupts traditional migration routes, preventing zebras from accessing seasonal grazing areas and water sources. This is particularly devastating for plains zebras, whose survival depends on following rainfall patterns across vast landscapes.

Competition with domestic livestock for grazing and water creates additional pressure, especially during droughts. Livestock often receive priority access to water and grazing in communal lands, pushing zebras into marginal habitats. In some areas, zebras are hunted for their meat and distinctive hides, though this is generally less intensive than historical hunting pressures.

Climate change increasingly threatens zebra populations by altering rainfall patterns, intensifying droughts, and shifting vegetation zones. Grevy’s zebras are particularly vulnerable, already living in marginal arid environments where even slight climatic shifts can have dramatic consequences. Disease also poses threats, with zebras susceptible to equine diseases like African horse sickness and anthrax. Stress from habitat fragmentation and human disturbance may increase disease susceptibility by weakening immune systems.

Reproduction and Life Cycle

Zebra reproduction varies somewhat by species, but all follow similar general patterns. Female zebras reach sexual maturity between 3-6 years of age, while males mature slightly later at 4-7 years, though they may not successfully establish breeding territories or harems until several years after reaching physical maturity.

Plains and mountain zebras, living in stable harem groups, mate year-round, though births often peak during wet seasons when food is most abundant. When a female comes into estrus, the dominant stallion guards her closely, preventing other males from approaching. Courtship involves the stallion approaching with lowered head and ears forward, sniffing and nuzzling the female. If receptive, she’ll allow mounting; if not, she may kick or flee.

Grevy’s zebras follow a different pattern due to their territorial system. Dominant males establish territories containing key resources like water and good grazing, then attempt to attract females entering their area. Mating occurs within these territories, with females choosing to enter based on territory quality and male fitness.

The gestation period lasts approximately 12-13 months for all zebra species. Females typically separate from the herd shortly before giving birth, seeking a secluded spot where they can deliver and bond with their newborn in relative safety. This isolation period lasts several days, allowing the foal to imprint on its mother and memorize her specific stripe pattern, voice, and scent. This imprinting is crucial, as foals must be able to identify their mothers within the busy, confusing environment of the herd.

Zebra foals are precocial, born with their eyes open, a full coat, and the ability to stand within minutes of birth. Within an hour, most can run, a critical survival adaptation given the constant predation pressure. Foals are born with brown and white stripes that gradually darken to black over several months. The mother nurses her foal for up to 16 months, though foals begin sampling grass within a week of birth and graze regularly by a few months old.

Young zebras remain with their birth herd for varying periods. Young females may stay indefinitely, eventually joining the breeding population of their natal herd or being recruited into another harem. Young males typically leave or are driven out by the dominant stallion at 1-3 years of age, joining bachelor herds where they learn social skills and develop strength before attempting to establish their own harems or territories.

Zebras have relatively long lifespans for medium-sized mammals. In the wild, plains zebras typically live 20-25 years, while mountain and Grevy’s zebras may reach similar ages under good conditions. In captivity, with protection from predators and disease, zebras can live into their 30s or even early 40s. Mortality is highest during the first year of life, with estimates suggesting 50% or more of foals may not survive to adulthood due to predation, disease, and starvation during droughts.

Population

The conservation status and population trends of zebras vary dramatically by species, reflecting different levels of habitat loss, competition, and human pressure. Understanding these differences is crucial for targeted conservation efforts.

Plains zebras are classified as “Near Threatened” by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), representing the most secure of the three zebra species. Current population estimates suggest between 500,000 and 750,000 plains zebras remain across Africa, with significant populations in protected areas like the Serengeti-Mara ecosystem, which hosts some 200,000 individuals. Despite these relatively robust numbers, plains zebra populations are declining in many areas outside protected zones due to habitat loss, human-wildlife conflict, and competition with livestock. Some subspecies face more severe threats—the Cape mountain zebra subspecies of the plains zebra has experienced significant declines.

Mountain zebras show a more complex conservation picture. The species as a whole is listed as “Vulnerable,” but the two subspecies face different challenges. The Cape mountain zebra experienced a dramatic population crash, dropping to fewer than 100 individuals in the 1930s due to hunting and habitat loss. Intensive conservation efforts, including protected breeding programs and habitat management, have resulted in a remarkable recovery, with current populations exceeding 5,000 individuals. Hartmann’s mountain zebra remains more numerous, with an estimated 25,000-27,000 individuals, primarily in Namibia, though populations are slowly declining due to habitat degradation and competition with livestock.

Grevy’s zebras face the most critical situation, listed as “Endangered” with populations having crashed by more than 85% since the 1970s. Current estimates suggest only about 2,500-3,000 individuals remain in the wild, with the vast majority in northern Kenya and a small population in Ethiopia. This dramatic decline resulted from hunting for their distinctive hides, habitat loss and degradation, competition with livestock, and political instability in their range countries. Conservation programs have stabilized some populations, but Grevy’s zebras remain precariously close to extinction in the wild.

Several factors complicate zebra conservation. Their need for large ranges and access to migration corridors conflicts with human land use patterns. Climate change threatens to intensify droughts and shift vegetation zones, particularly impacting species like Grevy’s zebra that already inhabit marginal environments. Additionally, zebras reproduce relatively slowly, with long gestation periods and extensive parental care, meaning populations cannot rapidly rebound from declines.

Conclusion

Zebras represent far more than their iconic stripes suggest. These resilient equines have evolved sophisticated adaptations—from their thermoregulating coats to their complex social structures—that have allowed them to thrive in African environments for millions of years. Yet despite their evolutionary success, zebras now face unprecedented challenges from habitat loss, climate change, and human encroachment. The dramatic differences in conservation status among the three species—from the relatively secure plains zebra to the critically endangered Grevy’s zebra—demonstrate that even superficially similar animals can face vastly different futures based on their specific ecological requirements and the pressures they face.

The story of zebras reminds us that conservation is not a one-size-fits-all endeavor. Protecting these magnificent animals requires preserving vast landscapes, maintaining migration corridors, managing human-wildlife conflicts, and supporting local communities who share the land with wildlife. As we move forward, the survival of zebras will depend on our willingness to make space for wild creatures in an increasingly crowded world—ensuring that future generations can still witness these living masterpieces galloping across the African plains, their bold stripes a testament to nature’s creativity and resilience.

Scientific Name: Equus quagga (Plains), Equus zebra (Mountain), Equus grevyi (Grevy’s)

Diet Type: Herbivore (Grazer)

Size: 47-60 inches tall at shoulder (varies by species)

Weight: 385-990 pounds (varies by species)

Region Found: Eastern and Southern Africa