Picture a massive barrel-shaped creature emerging from an African river at dusk, its pink-tinged skin glistening in the fading light, jaws yawning open to reveal tusks the size of bowling pins. This is the hippopotamus—an animal whose cuddly appearance masks one of nature’s most dangerous temperaments. Despite their rotund, almost comical physique that has made them favorites in children’s books and animated films, hippos are responsible for more human deaths in Africa than any other large animal, including lions, crocodiles, and elephants.

These semi-aquatic behemoths represent a fascinating paradox in the natural world: they’re closely related to whales despite their terrestrial lifestyle, they’re herbivores with enormous predatory weapons, and they’re among the most aggressive mammals on Earth despite spending most of their time lounging peacefully in water. Understanding the hippopotamus means confronting our assumptions about what makes an animal dangerous, and discovering just how extraordinary evolution’s experiments can be.

Facts

Here are some remarkable facts that reveal the hippopotamus’s hidden complexity:

- Hippos produce their own sunscreen: Their skin secretes a reddish, oily substance called “blood sweat” (though it’s neither blood nor sweat) that acts as a natural sunblock and antibiotic, protecting their sensitive skin from sunburn and infections.

- They’re surprisingly fast on land: Despite weighing up to 4,000 pounds, hippos can run at speeds of 19-30 mph in short bursts—faster than most humans—making them extremely dangerous when they charge.

- Hippos can’t actually swim: Rather than swimming, they walk or bounce along the bottom of rivers and lakes, pushing off with their feet to propel themselves through the water.

- Their closest living relatives are whales: Genetic studies have revealed that hippos are more closely related to cetaceans (whales and dolphins) than to other even-toed ungulates like pigs or cattle, despite their vastly different lifestyles.

- They engage in “muck spreading”: Male hippos mark their territory by rapidly spinning their tails while defecating, creating a spray that can reach distances of up to 10 feet to advertise their presence.

- Hippos can hold their breath for up to five minutes: Their nostrils, eyes, and ears are positioned on top of their heads, allowing them to remain almost completely submerged while still breathing and monitoring their surroundings.

- They have a unique vocal language: Hippos communicate through water and air simultaneously, producing calls that travel through both mediums, allowing them to maintain social bonds across their aquatic territories.

Species

The hippopotamus belongs to a taxonomic classification that places it among some surprising relatives:

Kingdom: Animalia

Phylum: Chordata

Class: Mammalia

Order: Artiodactyla (even-toed ungulates)

Family: Hippopotamidae

Genus: Hippopotamus

Species: Hippopotamus amphibius

The family Hippopotamidae once contained numerous species spread across Europe, Asia, and Africa, but today only two species survive. The common hippopotamus (Hippopotamus amphibius) is the larger and more well-known species, while the pygmy hippopotamus (Choeropsis liberiensis) is a much smaller, forest-dwelling cousin found only in West Africa. The pygmy hippo weighs only 400-600 pounds—less than a sixth of its massive relative—and lives a more solitary, terrestrial existence.

Within Hippopotamus amphibius, some researchers have proposed several subspecies based on geographic distribution and minor morphological differences, though these classifications remain debated. These potential subspecies include the East African hippo, the West African hippo, the Southern African hippo, and the now-extinct North African hippo. However, genetic studies have not consistently supported these divisions, and many scientists treat the common hippopotamus as a single, variable species.

The hippopotamus’s evolutionary family tree reveals fascinating extinct relatives, including the European hippopotamus (Hippopotamus antiquus) that roamed the continent until about 30,000 years ago, and various Malagasy hippos that inhabited Madagascar until human arrival drove them to extinction within the last millennium.

Appearance

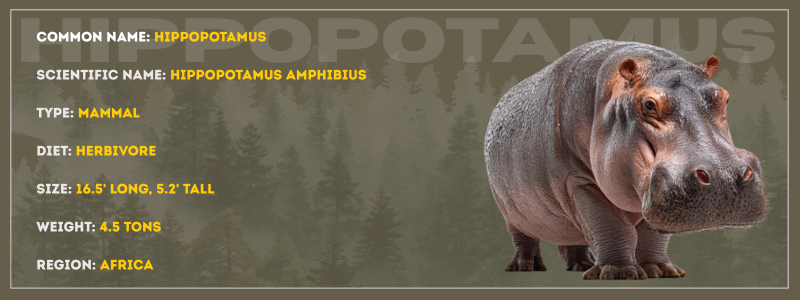

The hippopotamus is an imposing animal built like a living tank. Adult males typically measure 11 to 17 feet in length and stand about 5 feet tall at the shoulder, with females slightly smaller. Males commonly weigh between 3,300 and 4,000 pounds, though exceptional individuals may exceed 5,000 pounds. Their massive, barrel-shaped bodies are supported by surprisingly short, stumpy legs ending in four-toed feet, each toe webbed to aid movement through muddy riverbanks.

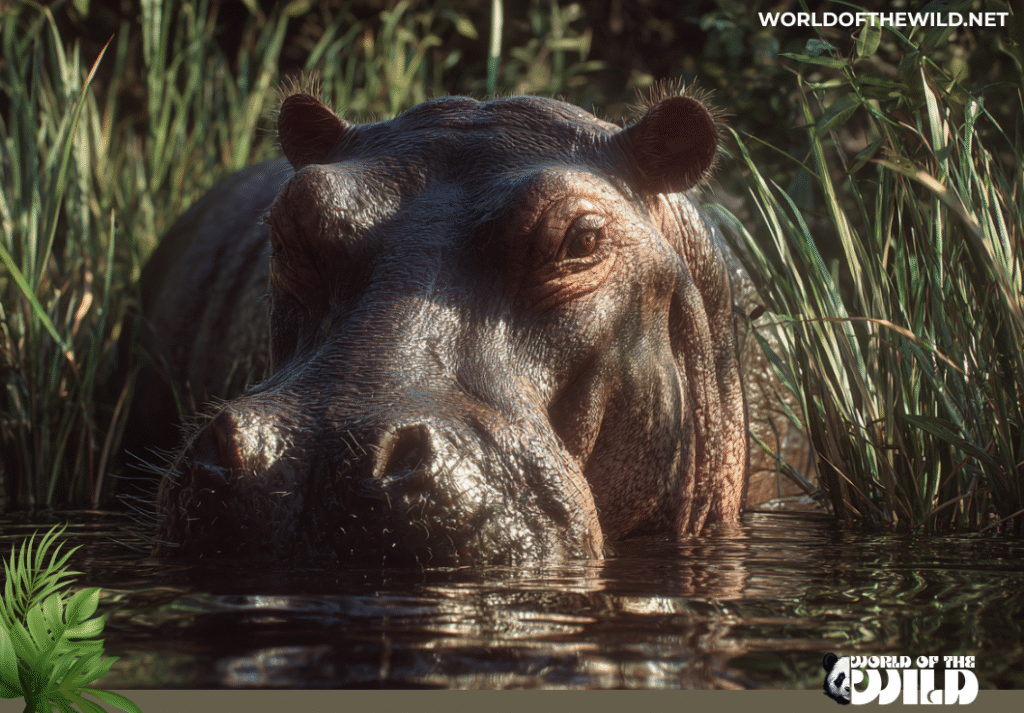

The hippo’s head is enormous and distinctly shaped, with a broad, flat muzzle and small, high-set eyes that protrude slightly from the skull. Their ears are small and rounded, capable of closing tightly when the animal submerges. The most striking feature is undoubtedly the mouth, which can open to an angle of 150 degrees, revealing a formidable array of teeth. The lower canine teeth are particularly impressive, growing continuously throughout the animal’s life and reaching lengths of up to 20 inches, with some exceptional tusks exceeding two feet. These ivory tusks, along with the razor-sharp incisors, form a deadly armament used primarily for combat with other hippos.

Hippo skin is thick—up to 6 inches in certain areas—but surprisingly delicate and sensitive to sunlight. The skin appears slate-gray to muddy brown on most of the body, with pink coloration around the eyes, ears, and ventral surfaces. This pinkness becomes more pronounced after extended time in water and when the animal secretes its protective “blood sweat.” The skin is almost entirely hairless except for a few bristles around the mouth and tail, leaving the hippo vulnerable to desiccation and sunburn, which explains their aquatic lifestyle.

Sexual dimorphism exists in hippos, with males being larger and heavier than females. Males also develop more pronounced facial features and larger canine teeth. Both sexes possess thick, muscular necks that support their massive heads during territorial battles and dominance displays.

Behavior

Hippopotamus behavior is defined by a strict daily rhythm dictated by their physiological limitations. As darkness falls, hippos emerge from rivers and lakes to graze on land, sometimes traveling up to six miles from water to find suitable vegetation. They spend five to six hours nightly feeding, following well-worn hippo paths that can be grooved two feet deep into the landscape after generations of use. Despite their massive size, hippos are solitary feeders, spreading out across grasslands to crop vegetation with their wide, muscular lips.

By dawn, hippos return to water, where they spend approximately 16 hours per day. In rivers and lakes, they gather in groups called pods, bloats, or sieges, typically numbering 10 to 30 individuals, though larger aggregations of over 100 hippos occur in prime habitat. These groupings follow a strict social hierarchy dominated by a territorial male who controls a stretch of riverbank and the females and subordinate males within it. The dominant bull maintains his position through impressive displays of aggression: yawning to display his massive tusks, mock charging, roaring, and when necessary, engaging in violent combat that can result in severe injuries or death.

Female hippos form the stable core of these groups, maintaining long-term associations and demonstrating cooperative behaviors like communal defense of young. Subordinate males are tolerated in the territory as long as they display submissive behavior, but they’re not permitted to mate. Young bachelor males often form loose all-male groups in marginal habitats until they’re strong enough to challenge for territory.

Communication among hippos is complex and multi-modal. Their vocalizations include grunts, bellows, roars, and a distinctive “wheeze honk” that carries for over a mile and helps maintain territorial boundaries. Remarkably, these calls propagate through both air and water simultaneously, creating a dual communication system. Underwater, hippos produce clicks and acoustic signals that travel efficiently through their aquatic environment. Visual displays—the famous jaw-gaping, head-swinging, and lunging—reinforce social hierarchies and territory ownership.

Hippos demonstrate surprising intelligence and memory. They recognize individual pod members, remember territorial boundaries established years earlier, and show problem-solving abilities in captivity. Their aggression toward humans and boats often stems not from mindless violence but from defensive behavior—protecting young, guarding territory, or preventing separation from water when they feel threatened on land.

Evolution

The evolutionary history of the hippopotamus reads like a tale of convergent evolution and ancient aquatic experimentation. Despite their pig-like appearance, molecular evidence definitively places hippos within Cetancodontamorpha, making them the closest living relatives of whales and dolphins. This extraordinary relationship stems from a common ancestor that lived approximately 55 to 60 million years ago during the early Eocene epoch.

The hippo lineage diverged from the cetacean lineage around 55 million years ago, while cetaceans took to the oceans, the ancestors of modern hippos remained semi-aquatic in freshwater environments. The family Hippopotamidae first appeared in the fossil record about 20 million years ago during the Miocene epoch in Africa. Early hippopotamids were more diverse than today’s survivors, with species varying considerably in size and ecological niche.

One key ancestor, Kenyapotamus, lived about 16 million years ago and already showed adaptations for semi-aquatic life, including high-positioned eyes and nostrils. The genus Hippopotamus itself emerged around 7 to 8 million years ago, and by the Pliocene and Pleistocene epochs, hippopotamids had spread throughout Africa, Europe, and Asia. Several island species evolved in isolation, including multiple species in Madagascar and Cyprus, demonstrating the hippo lineage’s evolutionary flexibility.

The most recent ice ages dramatically reduced hippo distribution. The European hippopotamus (Hippopotamus antiquus) thrived in temperate European rivers during interglacial periods but disappeared as climates cooled. Similarly, hippos once inhabited much of the Middle East and North Africa, with populations documented in ancient historical records from the Nile Delta region. Human hunting and climate change eliminated these populations within the last few thousand years.

The modern common hippopotamus represents a relatively conservative body plan that has remained largely unchanged for several million years—a testament to the successful adaptation of this semi-aquatic lifestyle. Their evolution demonstrates how a terrestrial mammalian lineage can readapt to aquatic life, converging on similar solutions to those found in cetaceans: high-positioned sensory organs, the ability to close nostrils underwater, modified limb structures for aquatic locomotion, and even changes in vocal communication to function in water.

Habitat

The common hippopotamus is endemic to sub-Saharan Africa, with populations distributed across the continent in a fragmented pattern that reflects both suitable habitat availability and human impacts. Historically, hippos ranged from the Nile Delta in Egypt southward throughout the continent, but their current distribution is much reduced, concentrated in East, Central, and Southern Africa. Significant populations exist in countries including Tanzania, Zambia, Mozambique, Zimbabwe, Uganda, Kenya, and South Africa, with smaller populations scattered across West and Central African nations.

Hippos are obligate aquatic mammals that require permanent water bodies deep enough for complete submersion—typically at least five feet deep. They inhabit rivers, lakes, swamps, and occasionally estuaries where freshwater meets the sea. The ideal hippo habitat combines these deep-water refuges with adjacent grasslands for nocturnal grazing. Rivers with slow-moving water and pools are preferred over fast-flowing currents, as hippos favor calm water where they can rest on the bottom while keeping their nostrils above the surface.

The specific characteristics of hippo habitat reveal their ecological requirements. Water temperature matters less than water permanence; hippos occupy environments ranging from the cool highlands of Ethiopia to the tropical heat of the Congo Basin, but they cannot survive where water bodies dry up seasonally. River sections with gently sloping, muddy banks provide ideal entry and exit points, while steep or rocky banks limit accessibility. Sufficient aquatic vegetation and suitable grazing areas within several miles of water are essential for population sustainability.

During the wet season, hippos may temporarily colonize seasonal pans and floodplains, but they inevitably return to permanent water as conditions dry. This seasonal movement pattern historically allowed hippo populations to exploit vast areas of floodplain habitat, though such movements are increasingly restricted by human development, agricultural expansion, and infrastructure that fragments landscapes.

Water quality affects hippo populations significantly. While hippos tolerate somewhat turbid water, extreme pollution or oxygen depletion can force abandonment of otherwise suitable habitat. Interestingly, hippos themselves profoundly impact their aquatic ecosystems through their daily defecation in water, which provides massive nutrient subsidies supporting fish populations and aquatic food webs.

Diet

The hippopotamus is an herbivore with a diet simpler than its massive bulk might suggest. Hippos are primarily grazers, feeding almost exclusively on grasses during their nocturnal foraging expeditions. They consume primarily short, creeping grasses, which they prefer over taller species, using their wide, muscular lips to pluck vegetation in a distinctive sweeping motion. An adult hippo consumes approximately 80 to 100 pounds of grass per night—relatively modest for an animal of its size, reflecting a surprisingly efficient digestive system and low metabolic rate.

The hippo’s feeding strategy involves cropping grasses very close to the ground, creating distinctive “hippo lawns” of closely grazed vegetation around water bodies. These lawns actually benefit certain plant species adapted to heavy grazing while altering local plant community composition. Hippos show preferences for certain grass species, particularly species in the genera Panicum, Themeda, and Cynodon, though they’ll consume whatever grasses are locally abundant.

While grasses constitute the overwhelming majority of their diet, hippos occasionally consume other vegetation including reeds, fallen fruit, and aquatic plants, though this represents a tiny fraction of total food intake. Contrary to popular belief, hippos rarely eat aquatic vegetation while in the water; they are nocturnal terrestrial feeders who return to water primarily for protection, thermoregulation, and social interaction.

Reports of hippos consuming meat or scavenging carcasses, while documented, represent abnormal behavior rather than typical dietary habits. Such instances may result from nutritional deficiencies, illness, or unusual environmental conditions. These observations, though sensational, do not reflect normal hippo feeding ecology.

The hippo’s digestive system is complex and specialized. They possess a three-chambered stomach (though not a true ruminant system like cattle) that allows microbial fermentation of plant material. This extended digestion process, combined with their sedentary lifestyle, allows them to extract maximum nutrition from relatively poor-quality forage. Their daily energy expenditure is remarkably low for such a large mammal, approximately 30 to 40 percent less than would be expected for a terrestrial mammal of equivalent size, which explains how they maintain their massive bodies on a purely grass diet.

Predators and Threats

Adult hippopotamuses have virtually no natural predators due to their size, aggression, and formidable weaponry. A healthy adult hippo is simply too dangerous for even Africa’s apex predators to attack. Lions, the continent’s premier large predators, generally avoid confrontation with adult hippos. However, young hippos face significant predation pressure from multiple carnivores.

Crocodiles, particularly large Nile crocodiles, are the primary predators of juvenile hippos, especially when youngsters become separated from protective adults in water. Lions, hyenas, and leopards also prey on young hippos when they encounter them on land during nocturnal grazing, though such opportunities are rare given the vigilance of mother hippos. Calves remain extremely vulnerable during their first year, and predation accounts for significant juvenile mortality in some populations.

Paradoxically, the greatest threat to young hippos often comes from adult male hippos themselves. Territorial bulls sometimes kill calves during aggressive encounters, particularly when challenging for territory or when calves inadvertently get caught between fighting males. This infanticide, while not a predation behavior per se, represents a significant natural mortality factor.

Human activities pose far greater threats to hippo populations than any natural predator. Habitat loss and fragmentation rank as the most severe challenges facing modern hippo populations. Agricultural expansion, dam construction, water extraction, and human settlement development have eliminated or degraded vast areas of former hippo habitat. Rivers and lakes that once supported large populations now face water diversion, pollution, and habitat modification that render them unsuitable for hippos.

Poaching for hippo ivory represents another critical threat. Hippo teeth are valued as an ivory source, particularly as elephant ivory trade restrictions have increased demand for alternatives. Thousands of hippos are killed annually for their teeth, which enter both legal and illegal ivory markets. Their meat is also valued in bushmeat trade throughout parts of Africa.

Human-wildlife conflict intensifies as human populations expand into hippo habitat. Hippos sometimes raid crops during nocturnal feeding, bringing them into direct conflict with farmers. Retaliatory killings and preventive hunting reduce populations in areas of high human density. Additionally, hippos’ reputation as dangerous animals leads to killing when they’re perceived as threats to human safety, particularly near fishing villages and agricultural areas.

Climate change presents an emerging threat by altering rainfall patterns and water availability. Increased drought frequency threatens to dry up seasonal and even some permanent water bodies, forcing hippos into smaller, more crowded refuges or eliminating habitat entirely. Competition for increasingly scarce water resources between humans and hippos exacerbates conflicts.

Reproduction and Life Cycle

Hippopotamus reproduction follows patterns typical of large, long-lived mammals with extended parental investment. Female hippos reach sexual maturity between five and six years of age, while males mature sexually around seven years but typically don’t achieve territorial dominance necessary for breeding until age 10 to 14 years. This delayed reproductive success in males results from intense competition for territories and the physical dominance required to maintain breeding access.

Breeding can occur year-round in hippo populations, though births often show seasonal peaks corresponding to optimal environmental conditions and food availability. In regions with pronounced wet and dry seasons, most births occur during the wet season when food is most abundant. Courtship and mating occur in water, where the buoyancy helps support the massive animals. The dominant territorial male courts receptive females within his territory through vocalizations, displays, and persistent pursuit.

Following successful mating, the gestation period lasts approximately eight months—240 to 255 days. As birth approaches, the pregnant female isolates herself from the pod, seeking a secluded area of water or riverbank for delivery. Birth typically occurs in shallow water or on land near water, with the mother immediately helping her newborn to the surface for its first breath if born underwater.

Hippo calves are precocial, born relatively well-developed and able to walk within hours. Newborns weigh between 50 and 110 pounds and can close their nostrils and ears instinctively when submerged. The mother-calf bond is intense and immediate. For the first several weeks, the mother isolates with her calf, allowing it to bond and gain strength before rejoining the pod. During this period, she is extraordinarily protective and highly aggressive toward any perceived threats.

Calves nurse both on land and underwater, with specially adapted nursing behavior that allows them to suckle while submerged by closing their nostrils and folding back their ears. Lactation continues for about one year, though calves begin supplementing milk with grass within a few months. Young hippos remain closely associated with their mothers for several years, gradually gaining independence.

The reproductive rate of hippos is relatively slow. Females typically produce one calf every two years under optimal conditions, though the interval can extend to three years or more if environmental conditions are poor or the previous calf dies. This slow reproductive rate makes hippo populations vulnerable to overhunting and limits their ability to recover from population declines.

Life expectancy in the wild typically ranges from 40 to 50 years, though some individuals may live longer. In captivity, with veterinary care and lack of predation pressure, hippos have lived past 60 years. Males generally have shorter lifespans than females due to the physical toll of territorial combat and competition.

Population

The hippopotamus is currently classified as Vulnerable on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, a designation that reflects significant population declines over recent decades. This status represents a deterioration from the species’ previous classification, highlighting growing conservation concerns.

Estimating global hippo populations is challenging due to their distribution across numerous countries and the difficulty of surveying aquatic animals in often remote locations. Current estimates suggest a total wild population of between 115,000 and 130,000 individuals, though uncertainty in these numbers is substantial. This represents a decline of 7 to 20 percent over the past decade, with declines varying significantly by region.

Population trends differ dramatically across the hippo’s range. Some populations, particularly in well-protected areas in East and Southern Africa, remain relatively stable or have even increased due to effective conservation management. Tanzania, Zambia, and Botswana harbor some of the largest remaining populations. Countries like Uganda, with approximately 5,000 to 10,000 hippos concentrated in protected areas like Queen Elizabeth National Park and Murchison Falls National Park, have maintained populations through active management.

However, populations have declined precipitously in West and Central Africa, where habitat loss, political instability, and inadequate protection have decimated former strongholds. The Democratic Republic of Congo’s hippo populations have suffered particularly severe declines due to civil conflict, poaching, and habitat degradation. Some countries have experienced localized extinctions, with hippos disappearing entirely from areas they once inhabited.

Regional conflicts and political instability have disproportionately impacted hippo populations, as conservation enforcement collapses during periods of violence and hippos are killed for food by displaced populations or armed groups. The situation in Virunga National Park in the DRC exemplifies this challenge, where ongoing conflict has reduced hippo numbers by over 90 percent in recent decades.

Climate change projections suggest that many hippo habitats will face increased water stress in coming decades, potentially exacerbating population pressures. Models predict that suitable habitat could contract significantly in some regions, forcing populations into smaller areas and intensifying human-wildlife conflicts.

Conclusion

The hippopotamus stands as one of Africa’s most remarkable yet misunderstood megafauna—an evolutionary marvel that bridged the gap between terrestrial and aquatic life millions of years ago and maintained that precarious balance through vast spans of time. These massive herbivores, armed with deadly tusks and legendary aggression, shape African freshwater ecosystems through their mere presence, fertilizing waters, creating grazing lawns, and maintaining habitats that countless other species depend upon.

Yet for all their strength and apparent dominance, hippos face an uncertain future. Their Vulnerable status reflects the accumulated pressures of habitat loss, poaching, climate change, and human-wildlife conflict that no amount of individual ferocity can overcome. The decline of hippo populations represents not just the potential loss of an iconic species, but the degradation of entire freshwater ecosystems and the cultural heritage of communities that have coexisted with these animals for millennia.

Conservation success stories from well-managed protected areas demonstrate that hippo populations can stabilize and even recover when given adequate protection and habitat. However, such successes require sustained commitment, adequate funding, and cooperation between conservation organizations, governments, and local communities. As human populations continue to expand across Africa, finding ways to share landscapes with hippos becomes increasingly urgent and increasingly complex.

The fate of the hippopotamus ultimately reflects our broader commitment to preserving Earth’s biodiversity in the face of unprecedented human impacts. These ancient animals, survivors of ice ages and continental changes, now depend on human choices for their continued existence. Supporting protected area management, combating ivory trade, promoting human-wildlife coexistence strategies, and addressing climate change represent pathways toward a future where hippos continue to emerge from African rivers at dusk, reminding us that nature’s most powerful forces often come in unexpected packages.