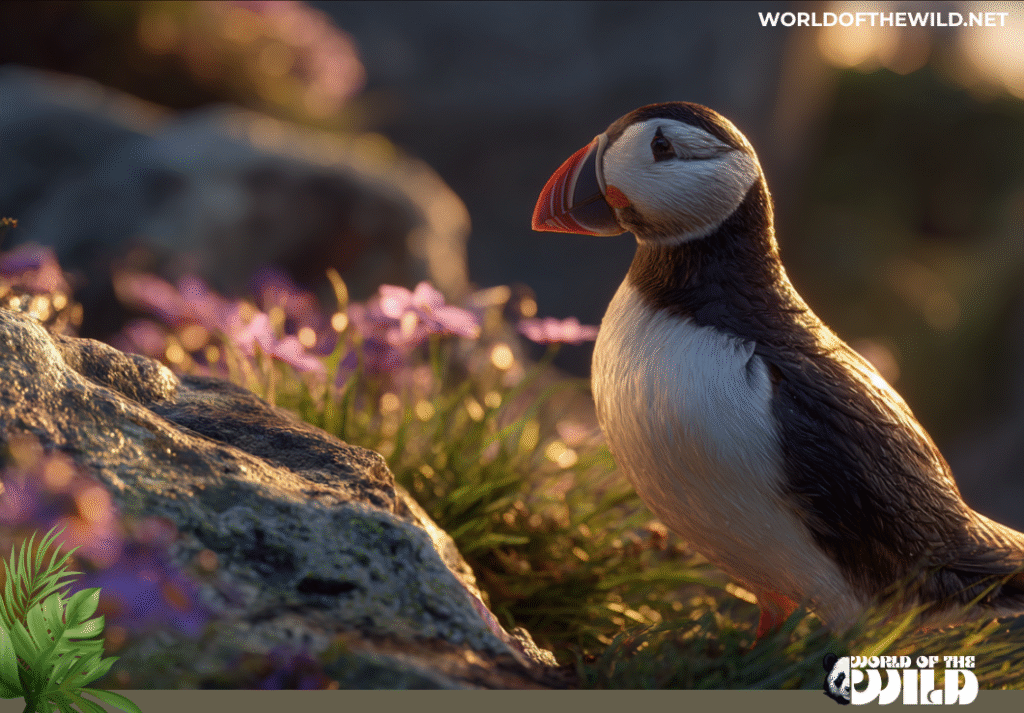

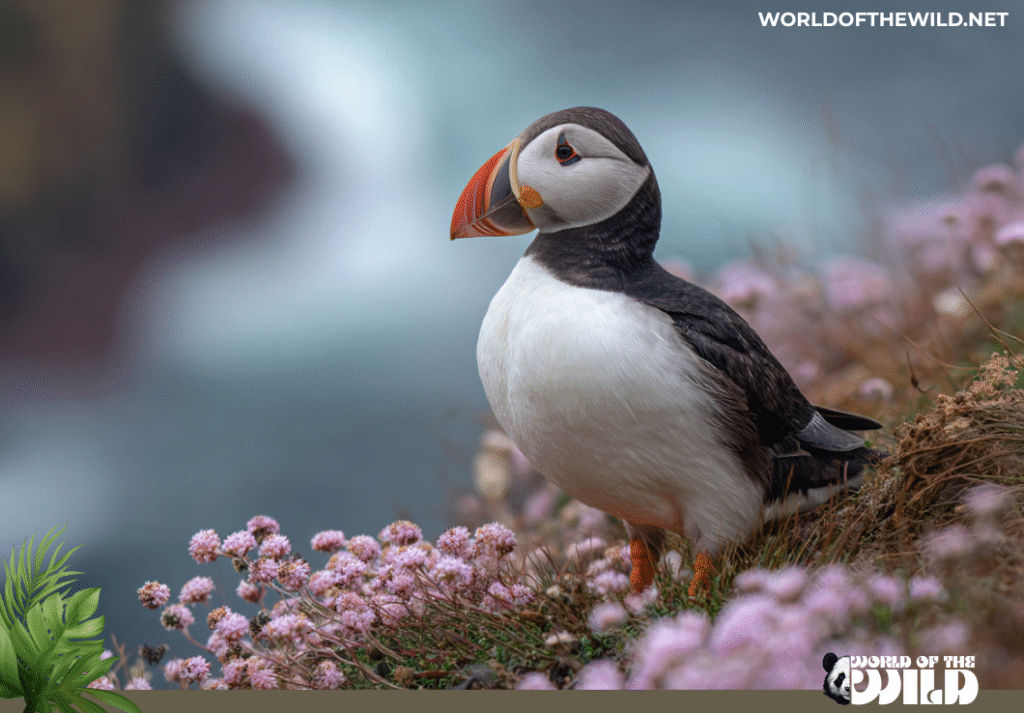

With its tuxedo-like plumage, comically oversized triangular beak blazing in shades of orange, red, and yellow, and an expression that seems perpetually surprised, the Atlantic Puffin looks less like a real bird and more like something dreamed up by a children’s book illustrator. Yet this charismatic seabird is very much real, spending most of its life riding the frigid waves of the North Atlantic Ocean with remarkable grace. Often called the “clown of the sea” or “sea parrot,” the Atlantic Puffin has captured hearts worldwide, becoming an emblem of coastal conservation efforts and a symbol of the wild, windswept places where land meets ocean. These remarkable birds represent a fascinating intersection of evolutionary adaptation, complex social behavior, and the delicate balance between marine ecosystems and human activity—making them not just adorable, but scientifically significant ambassadors of the ocean realm.

Facts

- Underwater Aviators: Atlantic Puffins can dive to depths exceeding 200 feet and remain submerged for up to a minute, using their wings to “fly” through the water at speeds reaching 55 miles per hour.

- Beak Color Change: The vibrant orange, red, and yellow coloration of a puffin’s beak is only present during breeding season; after mating, the outer colorful plates shed, revealing a smaller, duller beak for the winter months.

- Fish-Carrying Champions: Puffins can carry multiple fish—sometimes more than 60 at once—crosswise in their beaks thanks to backward-facing spines on their tongue and palate that hold prey in place while they continue hunting.

- Lifelong Partners: These birds typically mate for life, returning to the same burrow and the same partner year after year, with some pair bonds lasting over 20 years.

- Delayed Maturity: Atlantic Puffins don’t reach sexual maturity until they’re 4-5 years old, spending their early years entirely at sea, never touching land.

- Colonial Nesters: Puffin colonies can contain hundreds of thousands of individuals, creating vast “puffin cities” on remote islands and clifftops where the cacophony of calls creates an unforgettable soundscape.

- Salt Gland Adaptation: Special glands above their eyes allow puffins to drink seawater and excrete the excess salt, enabling them to survive indefinitely without freshwater.

Sounds of the Atlantic Puffin

Species

The Atlantic Puffin occupies a well-defined place in the tree of life:

- Kingdom: Animalia

- Phylum: Chordata

- Class: Aves

- Order: Charadriiformes

- Family: Alcidae

- Genus: Fratercula

- Species: Fratercula arctica

The genus Fratercula, whose Latin name means “little brother” (likely referring to the bird’s black and white plumage resembling monastic robes), contains two other puffin species: the Horned Puffin (Fratercula corniculata) and the Tufted Puffin (Fratercula cirrhata), both found in the North Pacific. While no recognized subspecies of the Atlantic Puffin exist, genetic studies have revealed subtle population differences between birds breeding in different regions, with North American colonies showing some genetic distinction from European populations.

The Atlantic Puffin belongs to the auk family (Alcidae), which includes razorbills, guillemots, murres, and the extinct Great Auk. These birds represent a remarkable example of convergent evolution with the unrelated penguins of the Southern Hemisphere, having independently evolved similar adaptations for pursuit diving and underwater swimming.

Appearance

The Atlantic Puffin is unmistakable in appearance, though its looks vary dramatically between seasons. During breeding season, adult puffins are striking birds measuring 10-12 inches in length with a wingspan of 20-24 inches and weighing between 14-17.5 ounces—roughly the size of a large pigeon but stockier. Their most famous feature is their massive, laterally compressed bill, which during breeding season displays brilliant bands of blue-gray at the base, yellow in the middle, and bright orange-red at the tip, with a yellow rosette at the corner of the mouth.

The body plumage presents a classic penguin-like pattern: the head features a black cap and collar with a distinctive white face mask and pale gray-white facial patches, while the back and wings are jet black, contrasting sharply with a pure white breast and belly. The legs and webbed feet glow with the same vivid orange as the bill. Perhaps most charming are the eyes, which appear large and rounded, surrounded by red orbital rings and small horn-like protrusions above each eye, with a small triangular gray-blue patch below—giving the bird its perpetually earnest expression.

In winter plumage, puffins transform dramatically. The colorful bill plates shed, leaving a smaller, duller bill. The face darkens as the white areas become grayish, and the overall appearance becomes considerably less flamboyant—an adaptation that likely reduces conspicuousness to predators during the vulnerable months at sea.

Sexual dimorphism is minimal, though males tend to be slightly larger than females. Juvenile puffins resemble winter adults but with even smaller, darker bills and generally duller plumage, not achieving full adult coloration until several years of age.

Behavior

Atlantic Puffins exhibit a fascinating duality in their behavior, living completely different lives depending on the season. During the breeding season (roughly April through August), they transform from solitary ocean wanderers into intensely social colonial nesters, gathering in densely packed colonies that can number in the tens or even hundreds of thousands of individuals. Within these bustling communities, puffins display complex social behaviors, including ritualized displays where pairs stand breast-to-breast and rapidly shake their heads from side to side, bills clacking together in a behavior called “billing” that reinforces pair bonds.

Communication within colonies involves a variety of vocalizations, including low growls and groans used within burrows, and higher-pitched calls used in territorial disputes. Despite their clumsy, almost comedic appearance on land—they waddle upright on their short legs and often tumble during takeoffs and landings—puffins are surprisingly aggressive when defending their burrow territories, engaging in fierce battles involving pecking, wing-beating, and grappling.

Their true mastery appears in the marine environment. Puffins are phenomenal divers, using their wings for underwater propulsion in a technique called wing-propelled diving. They literally fly through the water, executing sharp turns and rapid accelerations to pursue small fish. Their webbed feet serve as rudders, allowing precise maneuvering. When hunting, they typically make numerous shallow dives of 30-60 seconds, though they’re capable of much longer, deeper excursions when necessary.

A remarkable behavioral adaptation is their ability to carry multiple fish at once. By using backward-facing spines on their tongue and upper palate, they pin already-caught fish against the roof of their mouth while continuing to hunt, arranging their catch in neat rows, alternating head-to-tail for optimal packing. This allows parent birds to deliver more food per trip to their single chick, a crucial advantage when nesting sites may be considerable distances from productive fishing grounds.

From late August through early April, puffins abandon land entirely, dispersing across the North Atlantic. During these months, they become essentially silent and solitary, bobbing on the waves, diving for food, and sleeping on the water’s surface—never once returning to shore until the irresistible pull of breeding season calls them back to land.

Evolution

The evolutionary story of the Atlantic Puffin is intimately tied to the broader history of the auk family (Alcidae), a group that emerged during the Paleogene period, roughly 30-40 million years ago. The alcids evolved in the North Pacific, where most species diversity still exists today, before spreading into the North Atlantic through Arctic passages. The ancestors of modern auks were likely flying seabirds that gradually specialized for diving, trading aerial maneuverability for underwater performance—a compromise that resulted in the rapid, whirring wingbeats and sometimes awkward takeoffs characteristic of modern alcids.

The genus Fratercula (the true puffins) appears to be a relatively recent evolutionary development, probably arising within the last 5-10 million years during the Pliocene epoch. Fossil evidence of puffins is limited, partly because their bones are relatively fragile and their nesting sites on remote islands aren’t ideal for fossilization. However, skeletal remains and genetic studies suggest that the split between Atlantic and Pacific puffin species occurred as populations became isolated on opposite sides of the Arctic during glacial periods.

The Atlantic Puffin’s remarkable bill—its most distinctive feature—represents a fascinating evolutionary adaptation. The bright coloration serves multiple functions: sexual selection (brighter bills may indicate healthier, more fit individuals), species recognition, and possibly social signaling within colonies. The bill’s structure, broad and laterally compressed, creates less drag than might be expected when diving and may actually help in capturing and holding multiple slippery fish.

The evolution of wing-propelled diving required significant anatomical modifications. Puffins have solid bones (unlike the hollow bones of most flying birds), reducing buoyancy and making diving easier. Their wings are relatively small and stiff, optimized for underwater flight rather than efficient aerial travel. Their bodies are compact and streamlined, with powerful pectoral muscles that power both flight and underwater propulsion—a remarkable dual-purpose system that represents millions of years of refinement.

The seasonal shedding of colorful bill plates is a curious evolutionary feature rarely seen in birds. This allows puffins to invest energy in elaborate sexual signaling only when needed, reducing the costs of maintaining these structures during the non-breeding season when they would serve no purpose and might even attract unwanted attention from predators.

Habitat

Atlantic Puffins inhabit a specific band of the North Atlantic Ocean, roughly corresponding to cooler temperate and subarctic waters. Their breeding range extends from the northeastern coast of North America—including Maine, Newfoundland, Labrador, and Greenland—across Iceland, the Faroe Islands, Norway, the British Isles (especially Scotland, Wales, and Ireland), and south to the Brittany coast of France. The largest colonies exist in Iceland, which hosts 60-70% of the world’s Atlantic Puffin population, followed by significant populations in Norway, Scotland, and the Faroe Islands.

During breeding season, puffins require very specific terrestrial habitats: coastal islands, isolated clifftops, and headlands that offer protection from land-based predators like foxes and rats. They strongly prefer locations with soil deep enough for burrow excavation, typically choosing grassy clifftops, slopes, and boulder fields where they can dig nesting tunnels 2-3 feet deep. Some populations nest in rock crevices or beneath boulders when soil is unavailable. Access to the sea is critical—birds prefer nesting sites adjacent to deep water where they can depart and arrive with minimal predator exposure.

The surrounding marine environment must provide abundant food resources within reasonable flying distance. Puffins typically forage within 30 miles of their colonies, though they can travel farther if necessary. They favor areas where cold, nutrient-rich waters create conditions for high biological productivity, supporting large populations of small schooling fish.

Outside the breeding season, Atlantic Puffins become truly pelagic, meaning they live entirely on the open ocean, rarely if ever coming within sight of land. During these months, they disperse widely across the North Atlantic, with tracking studies revealing birds ranging from the waters off Newfoundland and Greenland across to the mid-Atlantic and down to the Canary Islands, Morocco, and even the western Mediterranean. They favor areas where ocean currents create upwelling zones rich in prey fish, spending their days floating on the surface, diving periodically to feed, and sleeping on the water—a lifestyle that requires remarkable adaptations to survive the North Atlantic’s notorious winter storms.

Diet

The Atlantic Puffin is an obligate carnivore, feeding exclusively on marine prey. Small fish comprise the vast majority of their diet, with specific prey species varying by location and season. In the western Atlantic, puffins primarily consume sand lance (sand eels), capelin, hake, herring, and sprat. In European waters, sand lance remains the dominant prey, supplemented by sprat, juvenile herring, and in some areas, Atlantic saury and juvenile cod.

The ideal prey fish measures 2-6 inches in length—small enough to capture and carry multiple individuals, but large enough to provide substantial nutrition. Puffins target young-of-the-year fish, which form dense schools in near-surface waters during summer months, making them relatively easy to locate and capture in large numbers. When feeding chicks, parent birds show remarkable selectivity, preferentially delivering high-lipid species like sand lance and capelin, which provide maximum energy for growing young.

Beyond fish, Atlantic Puffins occasionally consume marine invertebrates, including zooplankton (copepods and crustacean larvae), polychaete worms, small squid, and occasionally small mollusks. These invertebrates become more important during winter months when adults live at sea and may consume whatever is available. However, invertebrates lack the caloric density of fish and cannot sustain puffins long-term or support chick-rearing.

The hunting technique employed by puffins is remarkable in its efficiency. Foraging birds fly low over the water, scanning for signs of prey—often locating schools of fish by observing feeding activity by other seabirds or marine mammals. Once prey is detected, the puffin plunges into the water, immediately deploying its wings for propulsion. Underwater, they pursue fish with remarkable agility, executing tight turns and bursts of speed. When a fish is caught, the puffin uses its tongue to manipulate the prey crosswise in its bill, pinning it against backward-facing spines on the palate, leaving the bill tip free to catch additional fish. This allows parents to make fewer but more productive foraging trips—a critical adaptation when feeding demands are high.

Research has shown that successful foraging trips during breeding season typically result in catches of 10-30 fish, though exceptional hunters have been documented carrying over 60 fish at once. The average foraging trip lasts 30 minutes to several hours, depending on prey availability.

Predators and Threats

Despite spending most of their lives in the relatively safe open ocean, Atlantic Puffins face predation pressure during the breeding season when they’re tied to land-based colonies. The greatest natural predators are large gulls, particularly Great Black-backed Gulls and Herring Gulls, which patrol puffin colonies looking for opportunities to attack adults, steal fish being carried to burrows, or pull chicks from nesting sites. These aggressive predators have learned to target puffins arriving at colonies with beaks full of fish, forcing birds to either drop their catch or risk attack.

Avian predators also include skuas and jaegers, which engage in kleptoparasitism—harassing puffins in flight until they drop their fish. Peregrine Falcons occasionally take adult puffins, as do eagles in some regions. At sea, puffins face threats from below: large fish like cod and wolffish will snap up diving puffins, and marine mammals including seals occasionally prey on them.

On land, the most devastating predators are introduced mammals. Rats, particularly brown rats and black rats that have reached island colonies via human activity, can decimate puffin populations by consuming eggs and killing chicks in burrows. Mink, also introduced to many regions, are agile predators that can enter burrows and devastate entire colonies. Arctic Foxes pose threats in northern portions of the range, and feral cats have eliminated puffin colonies on some islands.

Anthropogenic threats, however, loom far larger than natural predation. Climate change represents the most significant long-term threat, affecting puffins through multiple pathways. Warming ocean temperatures are causing shifts in the distribution and abundance of prey fish, particularly sand lance, forcing puffins to fly farther to find food or switch to less nutritious prey. This leads to reduced chick survival and adult body condition. Changes in ocean temperature also affect plankton communities, creating mismatches between when puffin chicks need food and when prey fish are abundant.

Overfishing has severely depleted stocks of sand lance, herring, and other prey species in many areas, creating direct competition between commercial fisheries and seabirds. Industrial sand lance fisheries, used primarily for fishmeal and fish oil, remove millions of tons of fish that would otherwise support seabird populations.

Oil spills and chronic oil pollution cause significant mortality. Puffins are particularly vulnerable because they spend so much time on the water’s surface. Even small amounts of oil on plumage destroy waterproofing, leading to hypothermia and death. Major oil spills have killed thousands of puffins, and chronic low-level pollution from shipping takes an ongoing toll.

Bycatch in fishing gear, particularly gillnets, drowns puffins and other seabirds. Plastic pollution is an emerging threat, with birds ingesting microplastics directly or consuming contaminated prey fish. Ocean acidification, caused by rising atmospheric carbon dioxide, threatens to disrupt marine food webs in ways not yet fully understood.

Historical hunting pressure decimated many colonies. For centuries, puffins and their eggs were harvested for food, particularly in Iceland and the Faroe Islands. While subsistence harvesting continues in some areas at sustainable levels, past overharvesting reduced or eliminated many populations. On a positive note, legal protections now prohibit hunting in most of the puffin’s range.

Reproduction and Life Cycle

Atlantic Puffins exhibit a fascinating and highly ritualized reproductive cycle that begins with their return to breeding colonies in April. These birds demonstrate remarkable site fidelity, not only returning to the same colony but often to the exact same burrow year after year. Before breeding begins, established pairs engage in elaborate courtship displays, including the distinctive billing behavior where both birds stand upright, press their breasts together, and rapidly shake their colorful bills back and forth with a clacking sound that advertises their bond to the entire colony.

New pairs form through courtship displays that involve males standing outside promising burrow sites and repeatedly calling and displaying their colorful bills. Females evaluate potential mates based on bill size and coloration, burrow quality, and territorial displays. Once paired, the bond typically lasts for life, though divorces do occur, particularly after failed breeding attempts.

Nest preparation involves excavating or refurbishing burrows, which can take several weeks. Using their bills and powerful feet, puffins dig tunnels 2-3 feet long (though some extend to 6 feet) ending in a nesting chamber. Some pairs nest in rock crevices or under boulders, lining the space with grass, feathers, and seaweed to create a soft cup for the egg.

The female lays a single large white or slightly spotted egg, typically in late April or May. Both parents share incubation duties, which last 39-45 days. The adults take shifts lasting 12-30 hours, with the off-duty bird foraging at sea. This prolonged incubation period is characteristic of seabirds and reflects the high investment puffins make in each reproductive attempt.

The chick, called a puffling, hatches covered in thick black or dark brown down. For the first week, parents brood the chick constantly, keeping it warm, but thereafter the puffling is left alone in the burrow while both parents forage. Adults return regularly—typically 3-12 times per day—carrying beakfuls of fish. The puffling grows rapidly, and by 35-50 days after hatching, it weighs nearly as much as an adult, having been fed enormous quantities of high-fat fish.

The fledging process is dramatic and swift. Pufflings fledge at night, minimizing predation risk from gulls. When ready, the chick emerges from the burrow for the first time and, without any parental guidance, makes its way to the cliff edge and launches itself toward the sea. Many tumble and flutter more than fly during this maiden voyage, but they instinctively head toward the water. Once on the ocean, the newly independent juvenile is entirely on its own—parents provide no further care. The fledgling immediately disperses to sea, where it will remain for 3-5 years before returning to land for the first time since fledging.

Sexual maturity arrives at 4-6 years of age, though many birds don’t successfully breed until they’re even older. Young birds return to colonies as non-breeders, prospecting for burrows and potential mates, a process that may take several seasons before successful breeding occurs.

Atlantic Puffins are remarkably long-lived for their size. The oldest known wild Atlantic Puffin reached at least 41 years old, though average lifespan is more typically 20-25 years for birds that survive to adulthood. However, mortality is high in the first year of life, with only 50-60% of fledglings surviving their first year at sea.

Population

The Atlantic Puffin is currently classified as Vulnerable on the IUCN Red List, a designation that reflects significant population declines in many parts of its range. This represents a deterioration from its previous status of Least Concern, with the reclassification occurring in 2015 due to documented declines, particularly in European colonies.

The global population is estimated at approximately 6-7 million breeding pairs (12-14 million individual birds). Iceland hosts the vast majority—approximately 60-70% of the world population—with 3-4 million pairs. Norway holds roughly 1.5 million pairs, making it the second-largest population center. The United Kingdom hosts around 580,000 pairs, with significant colonies in Scotland (including St. Kilda, the Shetland Islands, and Orkney), Wales, and England. Ireland maintains approximately 25,000 pairs, and the Faroe Islands host around 500,000 pairs. In North America, populations are much smaller: eastern Canada has approximately 350,000 pairs, while Maine’s population has rebounded to roughly 3,000 pairs through intensive conservation efforts.

Population trends vary dramatically by region, painting a complex picture. Icelandic colonies, while still numerically dominant, have experienced concerning declines, with some colonies losing 50% or more of their populations since the 1990s. The southern extent of the range has seen particularly dramatic decreases, with colonies in France and southern Britain experiencing severe declines or local extinctions. Norwegian populations have also decreased in many areas, particularly in the south.

However, some populations show stability or even increases. Scottish colonies have remained relatively stable or increased in recent decades. Most remarkably, North American populations have rebounded dramatically from near-extinction in the early 20th century. Maine’s puffin population was reduced to a single colony of a few dozen pairs by the late 1800s due to hunting and egg collection. Through sustained conservation efforts, including Project Puffin’s innovative restoration techniques (using decoys and sound systems to attract puffins to restored islands), Maine now supports a thriving and growing population.

The overall trend, however, points toward decline, particularly in the species’ strongholds in Iceland and Norway. The primary drivers appear to be climate-driven changes in prey availability, with breeding success failing when sand lance and other key prey species become scarce. Years of low food availability lead to widespread breeding failures, with adults abandoning nests or chicks starving in burrows. Consecutive poor breeding years prevent population recruitment, and while adult survival remains relatively high, populations slowly contract without successful reproduction.

Monitoring efforts continue through coordinated seabird surveys, colony censuses, and increasingly, through advanced techniques including GPS tracking and population modeling. Conservation organizations across the Atlantic Puffin’s range recognize the species as a sentinel of ocean health, with population trends indicating the state of marine ecosystems. The shift to Vulnerable status has galvanized conservation efforts, with increased focus on marine protected areas, fishing restrictions near colonies, and climate change mitigation.

Conclusion

The Atlantic Puffin stands as one of nature’s most enchanting contradictions—a bird that waddles comically on land yet transforms into a masterful underwater hunter, a solitary ocean wanderer that becomes intensely social during breeding season, and a seemingly whimsical character that faces very serious conservation challenges. These remarkable seabirds have survived millions of years of evolution, perfecting their unique adaptations for life in one of Earth’s harshest environments: the cold, storm-tossed North Atlantic.

Yet today, puffins face unprecedented challenges. Climate change disrupts the delicate timing between breeding cycles and prey availability. Overfishing depletes the small fish they depend upon. Pollution, from oil spills to microplastics, contaminates their world. The shift to Vulnerable status reminds us that even species numbering in the millions can face rapid decline when environmental conditions change faster than evolution can respond.

The story of the Atlantic Puffin need not be one of loss. Recovery efforts in North America prove that dedicated conservation can bring these birds back from the brink. Every action we take to combat climate change, reduce ocean pollution, protect marine ecosystems, and manage fisheries sustainably helps ensure that future generations will witness puffins returning to their ancestral colonies each spring—bills blazing with color, wings whirring, ready to begin another breeding season in the wild places where sea meets sky. The clowns of the sea deserve nothing less than our most determined efforts to preserve both them and the magnificent ocean realm they call home.

Scientific Name: Fratercula arctica

Diet Type: Carnivore (piscivore)

Size: 10-12 inches (25-30 cm) in length; 20-24 inch (50-60 cm) wingspan

Weight: 14-17.5 ounces (400-500 grams)

Region Found: North Atlantic Ocean—breeding colonies from Maine to France; winters at sea across the North Atlantic