A blur of slate-gray feathers erupts from the backyard feeder as songbirds scatter in every direction. Perched on a nearby branch, eyes blazing with predatory focus, sits a Cooper’s Hawk—one of North America’s most skilled avian hunters. This medium-sized raptor has not only survived the modern world but thrived in it, adapting to suburban landscapes with remarkable success. Once persecuted to near-extinction, the Cooper’s Hawk has made a stunning comeback and now patrols neighborhoods across the continent, bringing the raw drama of predator and prey to kitchen windows everywhere. What makes this bird truly fascinating is its dual nature: a woodland phantom capable of threading through dense forest at breakneck speeds, yet equally at home hunting among backyard bird feeders and park picnic tables.

Facts

- Cooper’s Hawks can accelerate to speeds of nearly 40 mph while pursuing prey through dense woodland, executing hairpin turns around trees with astonishing precision.

- Despite their hunting prowess, young Cooper’s Hawks have a mortality rate of approximately 80% in their first year, making survival to adulthood a formidable challenge.

- These hawks have proportionally larger eyes than many other raptors, giving them exceptional visual acuity for tracking fast-moving prey through cluttered environments.

- Male Cooper’s Hawks are significantly smaller than females—sometimes up to 40% lighter—one of the most pronounced size differences among North American raptors.

- During courtship, males perform elaborate aerial displays including sky-dancing, undulating flights, and dramatic dives while calling to potential mates.

- Cooper’s Hawks can live surprisingly long lives for raptors, with the oldest known wild individual reaching over 20 years of age.

- They possess specialized flight feathers that reduce noise, allowing them to approach prey with exceptional stealth despite their relatively large size.

Sounds of the Cooper’s Hawk

Species

The Cooper’s Hawk belongs to the following taxonomic classification:

- Kingdom: Animalia

- Phylum: Chordata

- Class: Aves

- Order: Accipitriformes

- Family: Accipitridae

- Genus: Accipiter

- Species: Accipiter cooperii

Within the genus Accipiter, the Cooper’s Hawk shares close evolutionary relationships with other bird-hunting specialists. It is most closely related to the Sharp-shinned Hawk, which is smaller and often confused with juvenile Cooper’s Hawks, and the Northern Goshawk, a larger and more powerful forest predator. While no distinct subspecies of Cooper’s Hawk are currently recognized, individual populations show slight variations in size across their range, with northern birds typically larger than their southern counterparts—a pattern known as Bergmann’s rule. The genus Accipiter contains over 50 species worldwide, all characterized by short, rounded wings and long tails that enable exceptional maneuverability in forested habitats.

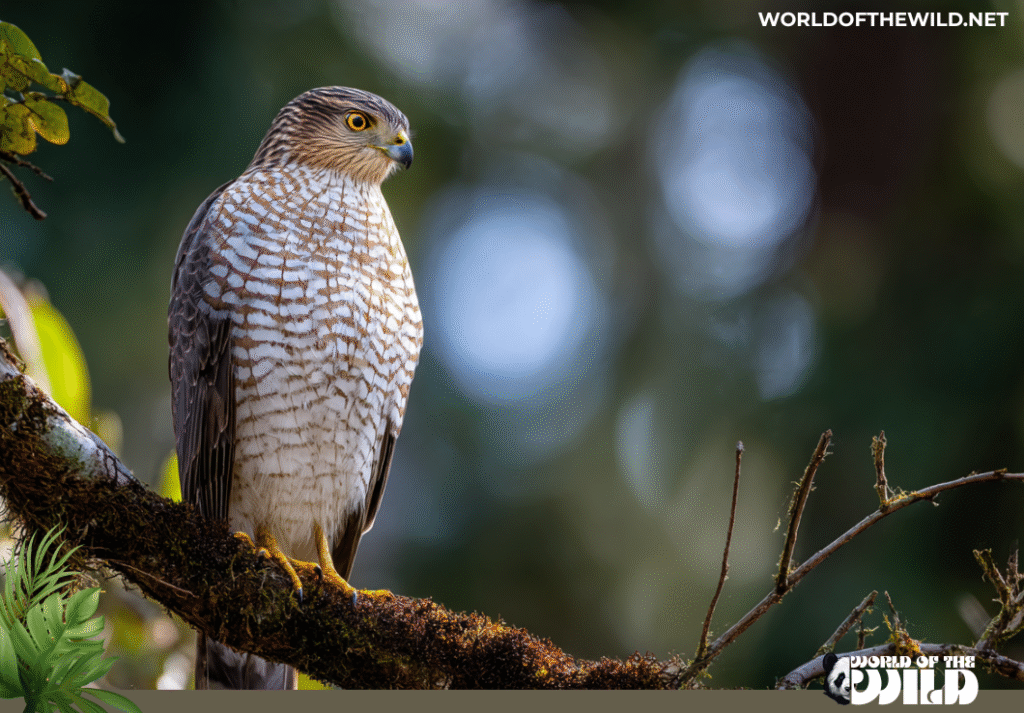

Appearance

The Cooper’s Hawk presents a striking silhouette perfectly engineered for woodland pursuit. Adults display a beautiful slate-blue or blue-gray back and crown, contrasting sharply with a white chest barred with rusty-orange horizontal streaks. Their tail features distinct dark bands with a white terminal band at the tip, creating a rounded appearance in flight. The eyes of adults are striking red or orange, giving them an intense, fierce expression that seems to pierce through their surroundings.

Males typically measure 14 to 16 inches in length with a wingspan of 24 to 35 inches, weighing between 8 to 14 ounces. Females are notably larger, measuring 16 to 20 inches long with wingspans reaching up to 39 inches and weights ranging from 11 to 24 ounces. This size dimorphism allows breeding pairs to hunt different-sized prey, reducing competition for food resources.

Juvenile Cooper’s Hawks look dramatically different from adults, sporting brown upperparts with white underparts heavily streaked with vertical brown stripes. Their eyes are yellow rather than red, gradually changing color as they mature. The hawk’s head appears somewhat flat-topped, and the tail shows a rounded tip—key identification features that distinguish them from the similar Sharp-shinned Hawk.

Their legs are long and thin but remarkably powerful, equipped with sharp, curved talons designed for grasping and killing bird prey. The middle toe is particularly elongated, allowing them to reach through branches and around obstacles to snatch fleeing victims.

Behavior

Cooper’s Hawks are solitary hunters outside the breeding season, exhibiting territorial behavior that keeps individuals dispersed across suitable habitat. They are most active during daylight hours, particularly in early morning and late afternoon when their prey species are most active at feeding sites.

Their hunting technique is breathtaking to witness. Unlike soaring hawks that hunt from great heights, Cooper’s Hawks employ ambush tactics, perching quietly in concealed locations before launching surprise attacks. They pursue prey with incredible agility, weaving through trees and around obstacles at high speed. This species demonstrates remarkable problem-solving abilities, learning the locations of bird feeders and returning to productive hunting grounds repeatedly. They’ve been observed waiting near feeders, using them as convenient prey aggregation sites.

Communication occurs primarily through vocalizations during breeding season. Both sexes produce a distinctive “cak-cak-cak-cak” call, with females having a noticeably lower-pitched voice. During courtship and territorial disputes, they become quite vocal, filling the woods with their harsh, chattering calls.

Cooper’s Hawks exhibit fascinating behavioral adaptations to avoid injury during high-speed pursuits. They can make instantaneous decisions about whether to continue a chase or abort based on obstacles in the flight path. Their exceptional spatial awareness and motor control allow them to execute maneuvers that seem to defy physics, pulling up sharply just inches from tree trunks or diving through impossibly narrow gaps.

One particularly interesting behavior is their tendency to pluck prey before consuming it. After a successful kill, they typically carry their catch to a preferred feeding perch where they methodically remove feathers, creating distinctive “plucking posts” scattered with telltale piles of feathers below.

Evolution

The evolutionary history of Cooper’s Hawks traces back to the diversification of the Accipitridae family, which began approximately 20 to 25 million years ago during the Miocene epoch. The genus Accipiter, which includes the forest hawks, evolved as specialized bird hunters, developing the characteristic short wings and long tail configuration that defines the group.

Fossil evidence for Cooper’s Hawks specifically is relatively sparse, as bird bones preserve poorly, but the species is believed to have emerged in North America during the Pleistocene epoch, roughly 2 million years ago. The harsh glacial cycles of this period likely influenced the hawk’s current distribution and migratory patterns, with populations repeatedly expanding and contracting with the ice sheets.

The evolutionary pressures that shaped the Cooper’s Hawk centered on the ability to pursue agile, fast-flying prey through complex, three-dimensional environments. This led to the development of specialized adaptations including enhanced visual processing for tracking moving targets, exceptional spatial awareness, and modifications to the wing and tail structure that prioritize maneuverability over speed in open flight.

The size dimorphism between males and females likely evolved as a strategy to reduce competition for prey resources between breeding pairs. With males hunting smaller birds like sparrows and warblers, and females capable of taking larger prey up to the size of doves and jays, a pair can exploit a broader range of food sources.

Cooper’s Hawks share a common ancestor with other Accipiter species, and their closest living relatives include the Sharp-shinned Hawk of North America and similar species found throughout the world. The genus represents a highly successful evolutionary design, with species occupying forested habitats on every continent except Antarctica.

Habitat

Cooper’s Hawks inhabit a remarkably broad geographic range across North America, from southern Canada through the United States and into Mexico and Central America. Their range extends from coast to coast, covering diverse climatic zones from temperate rainforests of the Pacific Northwest to the mixed hardwood forests of the East and the pine-oak woodlands of the Southwest.

Northern populations are migratory, moving south in autumn to escape harsh winters when prey becomes scarce. Birds from Canada and the northern United States migrate to the southern United States, Mexico, and occasionally Central America. Southern populations tend to be year-round residents, maintaining territories throughout the year.

The Cooper’s Hawk shows remarkable habitat flexibility. Historically, they were birds of mature deciduous and mixed forests, favoring woodlands with dense canopy cover and open understory that allowed them to maneuver while hunting. They prefer areas with a mix of forest types and age classes, utilizing tall trees for nesting while hunting in more open woodland edges and clearings.

In recent decades, Cooper’s Hawks have increasingly adapted to suburban and even urban environments. They now commonly nest in city parks, suburban neighborhoods, college campuses, and residential areas with sufficient tree cover. This adaptation has been so successful that some of the highest breeding densities now occur in suburban settings rather than wild forests. The abundance of prey at bird feeders, combined with reduced competition from larger raptors and the presence of suitable nest trees, has made human-modified landscapes highly attractive.

They select nest sites in mature trees, typically 25 to 50 feet above ground, often choosing conifers in mixed forests or deciduous trees in hardwood stands. The hawks prefer locations with good horizontal visibility beneath the canopy, allowing them clear flight paths for approaching the nest.

Diet

Cooper’s Hawks are specialized carnivores with a diet consisting almost exclusively of other birds. They are true avian predators, with birds comprising 90% or more of their prey intake. The size range of prey varies significantly between the sexes due to the pronounced size dimorphism.

Males primarily hunt small to medium-sized birds including sparrows, warblers, thrushes, and starlings—prey typically weighing between one to three ounces. Females, being substantially larger, target larger species such as jays, flickers, doves, and robins, capable of taking prey up to the size of a full-grown pigeon or young chicken.

Their hunting strategy relies on surprise and explosive acceleration. Cooper’s Hawks employ several techniques: still-hunting from concealed perches, where they wait motionless before launching sudden attacks; active pursuit through vegetation, where they chase fleeing birds through trees and shrubs; and low contouring flights, where they fly close to the ground using terrain and vegetation to conceal their approach until bursting over obstacles to strike surprised prey.

The hawks show remarkable adaptability in their hunting behavior. In suburban areas, they’ve learned to exploit bird feeders as hunting grounds, either by making direct strikes at feeding birds or by perching nearby and waiting for opportunities. They’ve been observed using buildings and fences for cover in the same way they use trees and topography in natural settings.

Small mammals occasionally supplement their diet, particularly during winter when bird populations decline or during breeding season when chicks require abundant food. Prey species include chipmunks, small squirrels, mice, and bats. Very rarely, they may take large insects, amphibians, or reptiles, but these represent only a tiny fraction of their diet.

After capturing prey, Cooper’s Hawks kill by repeatedly squeezing with their powerful talons, which can exert tremendous pressure. They typically carry prey to a safe feeding perch where they pluck feathers methodically before consuming the meat, leaving characteristic piles of feathers that mark their favorite dining locations.

Predators and Threats

Adult Cooper’s Hawks face relatively few natural predators due to their size, agility, and defensive capabilities. However, several larger raptors will prey on them opportunistically. Great Horned Owls are perhaps their most significant natural predator, hunting Cooper’s Hawks at their roosts during nighttime hours. Northern Goshawks, being larger and more powerful members of the same genus, occasionally kill Cooper’s Hawks, particularly in territorial disputes. Red-tailed Hawks may also prey on Cooper’s Hawks, especially juveniles or weakened individuals.

Nest predation poses a greater threat, particularly to eggs and nestlings. Raccoons, squirrels, American Crows, and Common Ravens will raid nests when adults are absent. Great Horned Owls also prey on nestlings during nighttime hours.

Historically, the greatest threat to Cooper’s Hawks came from deliberate human persecution. Throughout the early to mid-20th century, these hawks were shot in large numbers, considered “chicken hawks” and blamed for depredations on poultry. Additionally, the widespread use of DDT and other organochlorine pesticides from the 1940s through 1970s caused severe population declines. These chemicals accumulated in prey species and concentrated in the hawks, leading to eggshell thinning and reproductive failure.

Following the ban of DDT in 1972 and changing attitudes toward predators, Cooper’s Hawk populations have recovered remarkably. However, modern threats persist. Window collisions kill significant numbers, particularly in urban and suburban areas where hawks pursue prey near buildings with reflective glass. Vehicle strikes occur when hawks chase prey across roads or feed on road-killed animals.

Habitat fragmentation, while less impactful for this adaptable species than for many raptors, still affects some populations by reducing suitable nesting habitat. Climate change may alter prey availability and distribution, though the long-term impacts remain uncertain.

Backyard bird feeding, while providing abundant prey, may also expose Cooper’s Hawks to diseases concentrated at feeders, particularly trichomoniasis, a parasitic infection that can be fatal. Urban environments also expose hawks to various toxins including rodenticides, which accumulate when hawks consume poisoned prey.

Reproduction and Life Cycle

Cooper’s Hawks form monogamous pair bonds that typically last for multiple breeding seasons or even for life, though pairs may separate if breeding attempts fail repeatedly. The breeding season begins in early spring, with timing varying by latitude—March in southern regions and May in northern areas.

Courtship involves spectacular aerial displays. Males perform sky-dancing flights, flying in exaggerated undulations while calling loudly. They also execute dramatic high circling flights and power dives near potential nest sites. Males bring food offerings to females, strengthening pair bonds and demonstrating their hunting prowess.

Both members of the pair participate in nest construction, though the female typically does most of the building while the male gathers materials. They construct platforms of sticks and twigs in the crotch of a tree or against the trunk, often building on top of old nests from previous years or even appropriating abandoned nests of other species like crows or squirrels. The nest is lined with bark strips and greenery.

Females lay three to five eggs, typically four, with a pale blue or bluish-white color. Eggs are laid at two-day intervals. Incubation lasts approximately 30 to 36 days and is performed almost exclusively by the female, while the male provides food for her during this period.

Nestlings hatch covered in white down and are completely helpless. The female broods them closely for the first two weeks while the male continues to hunt and provision the family. As chicks grow, both parents hunt to meet increasing food demands. Young Cooper’s Hawks develop quickly, fledging at approximately 27 to 34 days old.

After fledging, young hawks remain dependent on their parents for another four to six weeks, gradually improving their flying and hunting skills. During this period, adults continue to provide food while youngsters practice capturing prey. Family groups break up by late summer as juveniles disperse to find their own territories.

Sexual maturity is reached at one to two years of age, though many individuals don’t breed successfully until their second or third year. Cooper’s Hawks can live surprisingly long lives for medium-sized raptors. Average lifespan in the wild is difficult to determine due to high juvenile mortality, but adults that survive their first year may live 10 to 12 years. The oldest known wild Cooper’s Hawk was over 20 years old, documented through bird banding records.

Population

The Cooper’s Hawk is currently classified as Least Concern by the International Union for Conservation of Nature, reflecting the species’ strong recovery and stable population trends. This represents a dramatic turnaround from the mid-20th century when populations were severely depressed due to persecution and pesticide contamination.

Current population estimates suggest there are approximately 700,000 to 1.2 million Cooper’s Hawks across their North American range. The species has shown consistent population increases since the 1970s, with some regional populations growing by 1 to 2% annually. Christmas Bird Count data and Breeding Bird Survey routes document this positive trend across most of the species’ range.

The recovery of Cooper’s Hawk populations stands as one of the conservation success stories of North American raptors. Several factors contributed to this resurgence: the banning of DDT and similar pesticides, legal protection under the Migratory Bird Treaty Act, changing public attitudes toward predators, and the species’ remarkable adaptability to human-modified landscapes.

Ironically, suburban sprawl—typically detrimental to wildlife—has in some ways benefited Cooper’s Hawks. Suburban areas provide abundant prey at bird feeders, suitable nest trees in parks and yards, and reduced competition from larger raptors that avoid human development. Some of the highest breeding densities now occur in suburban environments.

Population trends vary regionally. Populations are most robust in areas with extensive forest cover and in well-established suburban areas with mature trees. Some decline has been noted in heavily agricultural regions where both suitable nesting habitat and prey populations are reduced.

Conclusion

The Cooper’s Hawk embodies nature’s resilience and adaptability. From the brink of serious decline in the pesticide era to thriving populations hunting in suburban backyards today, this magnificent raptor has proven its ability to navigate the challenges of the modern world. Its presence in our neighborhoods offers a rare opportunity to witness predator-prey dynamics up close, reminding us that wild, untamed nature exists even in developed landscapes. As the slate-gray hunter perches in backyard trees, watching feeders with those intense orange eyes, it serves as both a testament to successful conservation efforts and a living reminder of our responsibility to protect the natural world. Whether you view the Cooper’s Hawk as a beautiful wild predator or a challenging visitor to your bird feeders, one thing is certain: this adaptable raptor will continue to thrive wherever birds congregate and trees stand tall enough to hold its nest. In protecting the habitats and prey species that support Cooper’s Hawks, we ensure that future generations can experience the thrill of watching these aerial masters command the skies.

Scientific name: Accipiter cooperii

Diet type: Carnivore (specialized bird predator)

Size: 14-20 inches (35-50 cm) in length; wingspan 24-39 inches (60-99 cm)

Weight: 8-24 ounces (220-680 grams); males 8-14 oz, females 11-24 oz

Region found: Throughout North America from southern Canada to Mexico and Central America; found in forests, woodlands, and increasingly in suburban and urban environments