Soaring high above open fields and perched majestically on roadside telephone poles, the Red-Tailed Hawk is a bird that commands attention. With its piercing gaze and distinctive russet tail glinting in the sunlight, this powerful predator has become synonymous with the wild skies of North America. You’ve likely heard its call in countless movies and television shows—that iconic, spine-tingling screech that filmmakers use to represent any bird of prey, from eagles to falcons. But the Red-Tailed Hawk is far more than just a Hollywood sound effect. As one of the most widespread and adaptable raptors on the continent, this remarkable bird plays a crucial role in maintaining ecological balance while demonstrating an extraordinary ability to thrive alongside human development. From the forests of Alaska to the deserts of Mexico, the Red-Tailed Hawk’s success story offers a fascinating glimpse into the life of a master aerial hunter.

Facts

- Red-Tailed Hawks can spot a mouse from 100 feet in the air, thanks to vision that’s approximately eight times sharper than human eyesight, allowing them to detect ultraviolet light that reflects off rodent urine trails.

- Despite their fierce reputation, Red-Tailed Hawks are devoted parents, with pairs often mating for life and returning to the same nesting territory year after year, sometimes for decades.

- The famous “eagle cry” heard in movies is actually the vocalization of a Red-Tailed Hawk—Bald Eagles produce a much weaker, more chattering sound that filmmakers consider unimpressive.

- These hawks have been observed using incredibly sophisticated hunting techniques, including cooperative hunting with other hawks and even waiting patiently near active fires to catch prey fleeing the flames.

- A Red-Tailed Hawk named Pale Male became a celebrity in New York City, successfully raising dozens of chicks while nesting on a Fifth Avenue apartment building across from Central Park, proving the species’ remarkable adaptability to urban environments.

- Red-Tailed Hawks can survive in temperatures ranging from Arctic cold to desert heat, adjusting their metabolism and behavior to thrive in climates where few other raptors can persist.

- Their talons exert crushing force of approximately 200 pounds per square inch—roughly equivalent to the bite force of a large dog—capable of instantly killing prey much larger than themselves.

Sounds of the Red Tailed Hawk

Species

The Red-Tailed Hawk belongs to the following taxonomic classification:

Kingdom: Animalia

Phylum: Chordata

Class: Aves

Order: Accipitriformes

Family: Accipitridae

Genus: Buteo

Species: Buteo jamaicensis

The Red-Tailed Hawk exhibits remarkable geographic variation, with at least 14 recognized subspecies distributed across North America, Central America, and the Caribbean. These subspecies vary considerably in size, coloration, and habitat preference. The most widespread is B. j. calurus, the Western Red-Tailed Hawk, which displays the darkest plumage morphs. B. j. borealis, the Eastern Red-Tailed Hawk, is the nominate subspecies and the most familiar form across the eastern United States and Canada.

Notable subspecies include B. j. harlani, Harlan’s Hawk, which was once considered a separate species and displays almost entirely dark plumage with a whitish tail; B. j. fuertesi, the Fuertes’s Red-Tailed Hawk of the southwestern deserts and northern Mexico, which is notably pale; and B. j. alascensis, the Alaska Red-Tailed Hawk, one of the largest and darkest forms. The Krider’s Hawk (B. j. kriderii), found in the northern Great Plains, is exceptionally pale, sometimes appearing almost white.

The genus Buteo includes numerous other hawk species, such as the Rough-legged Hawk, Ferruginous Hawk, and Swainson’s Hawk, all of which share the Red-Tailed Hawk’s robust body structure and soaring flight style but occupy different ecological niches.

Appearance

The Red-Tailed Hawk is a large, stocky raptor with broad, rounded wings and a relatively short, wide tail—the very tail that gives the species its name. Adults typically measure 18 to 26 inches in length, with females noticeably larger than males, a common trait among raptors known as reverse sexual dimorphism. Their wingspan is impressive, ranging from 38 to 43 inches for males and 45 to 52 inches for females, allowing for the effortless soaring flight that makes them such a familiar sight.

Weight varies considerably by sex and geography, with males typically weighing between 1.5 and 3.1 pounds, while larger females range from 2 to 4 pounds. The largest subspecies can occasionally exceed these ranges.

The defining feature is, of course, the tail. Adult Red-Tailed Hawks sport a distinctive rufous or brick-red tail that’s particularly striking when backlit by the sun. However, this characteristic doesn’t appear until the bird reaches maturity at around two years of age. Juvenile birds have brown tails marked with numerous dark bands.

Plumage varies dramatically across the species’ range, with individuals ranging from nearly pure white to almost entirely dark chocolate brown. The most common form—the “typical” light morph—features a brown back and head, a creamy white breast with a distinctive dark belly band formed by streaked markings, and dark brown streaking on the shoulders forming a “patagial bar” visible on the leading edge of the wing in flight. Dark morph individuals are uniformly dark brown except for their red tail and light flight feathers visible from below.

The head is broad and powerful, with a relatively short, sharply hooked yellow beak designed for tearing flesh. The eyes are dark brown, set forward on the face to provide the binocular vision essential for hunting. Like all raptors, they have a prominent brow ridge that gives them a perpetually fierce expression. Their legs and feet are yellow, ending in black, curved talons that are their primary weapons—the hallux (back toe) and the opposing front toe being particularly large and powerful for gripping struggling prey.

Behavior

Red-Tailed Hawks are generally solitary or found in pairs, though during migration and winter months, loose aggregations may form in areas with abundant prey. They’re not particularly social birds compared to some raptors, maintaining strict territorial boundaries during the breeding season that they defend vigorously against intruders, including other Red-Tailed Hawks.

These hawks are diurnal hunters, most active during the day, especially in the early morning and late afternoon hours. They employ several hunting strategies, though the most characteristic is the “sit-and-wait” technique. A Red-Tailed Hawk will perch motionless on an elevated vantage point—a dead tree, utility pole, fence post, or building ledge—scanning the ground below with those remarkable eyes. When prey is spotted, the hawk launches into a swift, controlled dive, often at speeds exceeding 120 miles per hour, striking with outstretched talons at the last moment.

They also hunt while soaring, using their broad wings to ride thermal air currents with minimal energy expenditure, gaining altitude while surveying vast territories below. When prey is spotted from this aerial position, they transition into a dramatic stoop, folding their wings partially and accelerating downward.

Red-Tailed Hawks are highly intelligent birds capable of learning and problem-solving. They’ve been observed adapting their hunting techniques to local conditions, such as waiting near prescribed burns to catch fleeing rodents, or timing their hunts to coincide with agricultural activities that flush prey into the open. Urban-dwelling hawks have learned to hunt at night under streetlights, taking advantage of rats and other nocturnal prey that humans inadvertently concentrate.

Communication involves both vocalizations and physical displays. Their call is a distinctive, raspy scream lasting two to three seconds—a sound transcribed as “kree-eee-ar” that carries for considerable distances. This vocalization serves multiple purposes: proclaiming territory, communicating with mates, and intimidating intruders. During courtship and territorial disputes, Red-Tailed Hawks engage in spectacular aerial displays, circling together at great heights, sometimes locking talons and spiraling toward the earth before separating at the last moment.

Pairs that mate often remain together year-round in non-migratory populations, strengthening their bond through mutual preening and cooperative nest maintenance. This long-term pair bonding contributes to their reproductive success, as experienced pairs work together more efficiently in territory defense and chick-rearing.

Evolution

The Red-Tailed Hawk’s evolutionary history traces back tens of millions of years to the Oligocene epoch, when the earliest raptor ancestors began diversifying into the forms we recognize today. The family Accipitridae, which includes hawks, eagles, and kites, diverged from other birds of prey approximately 50 million years ago during the Eocene.

The genus Buteo—the “buteos” or soaring hawks—represents a more recent evolutionary development, likely emerging during the Miocene epoch around 15 to 20 million years ago. These birds evolved the characteristic broad wings and robust bodies that make them masters of soaring flight, an energy-efficient hunting style perfectly suited to open and semi-open habitats.

The Red-Tailed Hawk itself likely evolved in North America, where it radiated into numerous subspecies as populations became isolated in different geographic regions following the glacial cycles of the Pleistocene. During ice ages, populations were pushed southward into refugia—isolated pockets of suitable habitat—where they developed distinct characteristics. As glaciers retreated, these populations expanded and sometimes came back into contact, leading to the complex pattern of variation we see today.

The species’ closest relatives include other large Buteo hawks of the Americas, particularly the Ferruginous Hawk and the Rough-legged Hawk. Genetic studies suggest that the Red-Tailed Hawk forms part of a New World buteo lineage that colonized the Americas from Eurasia during the Pliocene, subsequently evolving into distinctly American forms.

Fossil evidence of Buteo species from the Pleistocene shows that birds very similar to modern Red-Tailed Hawks existed at least 250,000 years ago. The species’ remarkable adaptability—its ability to thrive in diverse habitats from forest to desert—has been key to its evolutionary success and its survival through dramatic climate shifts that eliminated less flexible species.

Interestingly, the Red-Tailed Hawk’s evolution has been shaped by its prey. The abundance of small to medium-sized mammals in North America, particularly rodents and rabbits, created an ecological niche that the Red-Tailed Hawk exploited superbly. Their physical characteristics—from wing shape to talon structure—reflect millions of years of refinement for hunting these specific prey types in open country.

Habitat

The Red-Tailed Hawk is one of the most geographically widespread raptors in the Western Hemisphere, with a breeding range extending from central Alaska and northern Canada southward through the United States, Mexico, Central America, and into the Caribbean. This vast distribution encompasses an extraordinary diversity of habitats, testifying to the species’ remarkable ecological adaptability.

Northern populations are migratory, moving southward in autumn to escape harsh winters when prey becomes scarce beneath snow and ice. These migrants may travel hundreds or even thousands of miles, with hawks from Alaska and Canada wintering as far south as Mexico and Central America. In contrast, birds resident in the southern United States, Mexico, and Central America remain on their territories year-round.

The Red-Tailed Hawk’s habitat preference is characterized by a need for two essential features: open or semi-open hunting grounds and elevated perching sites. They thrive in a mosaic of habitats including grasslands, prairies, agricultural fields, desert scrublands, savanna, forest edges, and woodland clearings. The key requirement is access to prey-rich open ground combined with scattered trees, cliffs, or artificial structures for perching and nesting.

In the western United States, they inhabit everything from coastal regions to high mountain valleys, from saguaro deserts to Great Basin sagebrush country. Eastern populations favor a mix of deciduous and mixed forests interspersed with fields and meadows. In the northern boreal forests, they occupy clearings, river valleys, and forest edges rather than deep interior forest.

What’s particularly remarkable is the Red-Tailed Hawk’s successful colonization of urban and suburban environments. Major cities across North America now host breeding populations that nest on building ledges, bridges, and transmission towers, hunting in parks, golf courses, and even small patches of green space. They’ve learned to navigate human-dominated landscapes, taking advantage of the concentrated prey populations that human activities often create—particularly rodents attracted to human food waste and landscaping.

The species occupies elevations from sea level to over 10,000 feet in mountainous regions, though they’re most common below 8,000 feet. In desert environments, they concentrate along riparian corridors where trees provide nesting sites and prey is more abundant. In agricultural regions, they often hunt along field margins, ditches, and fence lines where small mammals concentrate.

Diet

The Red-Tailed Hawk is a carnivorous predator specializing in small to medium-sized mammals, though its diet is remarkably diverse and adaptable to local prey availability. This dietary flexibility is one of the key factors in the species’ widespread success.

Small mammals constitute approximately 85-90 percent of the Red-Tailed Hawk’s diet across most of its range. Voles, mice, rats, ground squirrels, and cottontail rabbits are staple prey items. In many regions, voles of the genus Microtus are particularly important, with a single breeding pair of hawks potentially consuming hundreds of these rodents during a single nesting season. The California ground squirrel is a primary prey species in the western United States, while eastern populations rely heavily on meadow voles and Eastern cottontails.

Prairie dogs represent important prey in grassland ecosystems, though taking these larger, colonial rodents requires considerable skill and often cooperative hunting between mated pairs. Tree squirrels are occasionally taken, though their agility in trees makes them more challenging prey than ground-dwelling species.

Beyond mammals, Red-Tailed Hawks will consume birds when opportunity arises, including species ranging from small songbirds to medium-sized game birds like pheasants and quail. Urban hawks have been documented taking pigeons, starlings, and even waterfowl from park ponds. During winter when mammals may be less accessible, birds can constitute a larger proportion of the diet.

Reptiles and amphibians supplement the diet, particularly in warmer climates and during summer months. Snakes—including rattlesnakes and other venomous species—are taken with apparent immunity to venom, likely because the hawk’s striking speed and crushing talons dispatch the snake before it can effectively defend itself. Lizards, particularly larger species, are captured opportunistically.

Less commonly, Red-Tailed Hawks will consume larger invertebrates such as grasshoppers, beetles, and occasionally crayfish in wetland environments. Fish are rarely taken but have been documented. Carrion is consumed when encountered, particularly in winter when hunting is more challenging, though Red-Tailed Hawks are primarily active hunters rather than scavengers.

Hunting strategy varies with prey type. Small rodents are typically captured during short flights from perches or after a stoop from soaring flight. Larger prey like rabbits may be pursued in extended tail-chases across open ground. The hawk uses its powerful talons to grasp and crush prey, often killing instantly through trauma or asphyxiation. The sharp, hooked beak is then used to tear flesh into manageable pieces.

A Red-Tailed Hawk typically consumes 10-15 percent of its body weight daily, though they can survive several days without food by metabolizing fat reserves. During the breeding season, prey requirements increase dramatically as adults must feed multiple growing chicks, each of which may consume its own body weight in food every few days.

Predators and Threats

Despite being an apex predator themselves, Red-Tailed Hawks face threats from both natural predators and human activities, particularly during vulnerable life stages.

Adult Red-Tailed Hawks have few natural predators due to their size, power, and aerial prowess. However, Great Horned Owls represent their most significant natural enemy. These powerful nocturnal hunters occasionally kill adult Red-Tailed Hawks on their roosts at night and regularly prey on hawk eggs and nestlings. In some regions, Golden Eagles may attack Red-Tailed Hawks, viewing them as competitors or even prey. Northern Goshawks, though smaller, are extremely aggressive and have been known to kill Red-Tailed Hawks during territorial disputes.

Eggs, nestlings, and fledgling hawks are more vulnerable. Beyond Great Horned Owls, raccoons, American crows, and common ravens will raid nests when adult hawks are absent, consuming eggs or small chicks. On the ground, coyotes, foxes, and bobcats may capture young hawks that have fallen from nests or are still developing flight skills.

Anthropogenic threats pose more significant challenges to Red-Tailed Hawk populations. Vehicle collisions are a major source of mortality, as hawks hunting from roadside perches or feeding on roadkill are struck by passing traffic. Electrocution on power lines kills substantial numbers annually, occurring when hawks perch on utility poles and their wings simultaneously contact two wires or a wire and ground.

Rodenticides present an insidious threat through secondary poisoning. Hawks that consume rodents killed by anticoagulant poisons accumulate these toxins in their tissues, leading to internal bleeding and death. This problem has become particularly severe in areas with extensive rodent control programs.

Illegal shooting, though declining, still occurs despite federal protections. Some individuals mistakenly view hawks as threats to poultry or game birds, though studies show domestic chickens and game species constitute minimal portions of their diet.

Habitat loss affects Red-Tailed Hawks less than many raptors due to their adaptability, but conversion of open hunting habitat to intensive development can locally reduce populations. Climate change may alter prey distribution and abundance, potentially impacting hawk populations in certain regions.

Wind turbines represent a growing concern, with raptors including Red-Tailed Hawks occasionally killed by blade strikes, though mortality rates are generally lower than for some other bird groups.

Lead poisoning from ingesting bullet fragments in gut piles and carcasses left by hunters affects some populations, though this threat is more significant for scavenging raptors.

The West Nile virus has caused mortality in some Red-Tailed Hawk populations, though most individuals appear to survive infection.

Reproduction and Life Cycle

Red-Tailed Hawks reach sexual maturity at approximately two years of age, coinciding with the development of their characteristic red tail plumage. Pair formation often occurs during spectacular courtship displays that begin in late winter or early spring.

Courtship involves elaborate aerial performances. Pairs soar in wide circles at great heights, calling to each other. The male performs undulating sky-dances, diving and climbing in roller-coaster patterns. In the most dramatic display, both birds gain altitude, then approach each other and briefly grasp talons, spiraling downward together before separating. These “talon-grappling” displays serve both courtship and territorial defense functions.

Once bonded, pairs typically remain together for life, reuniting each year at the same nesting territory. This fidelity to place is remarkable—some nesting sites have been occupied continuously for decades, though not necessarily by the same individual birds.

Nest construction or renovation begins several weeks before egg-laying. Red-Tailed Hawks build large stick nests typically placed 15 to 90 feet high in tall trees, on cliff ledges, or increasingly on artificial structures like building ledges and transmission towers. The nest is a substantial platform of sticks lined with bark strips, moss, and fresh green vegetation that’s added throughout the nesting period. Established pairs often maintain multiple nests within their territory, alternating between them across years.

The female lays one to five eggs, with two to three being most common, at intervals of two to three days. The eggs are white or pale blue, occasionally marked with brown spots. Incubation begins with the first or second egg and lasts approximately 28 to 35 days. The female performs most incubation duties, though males occasionally take brief turns, and the male provides food throughout this period.

Chicks hatch asynchronously, covered in white down, with eyes closed. This age difference between siblings can lead to competitive dynamics, with the oldest chick sometimes dominating food distribution or, in extreme cases, attacking younger siblings—a phenomenon called “cainism.” However, in years with abundant prey, most chicks survive.

Both parents provision the growing young, with prey delivery rates increasing dramatically as chicks grow. Young hawks develop rapidly, reaching adult weight within five to six weeks. Feather development progresses from down to juvenile plumage, which is fully formed by fledging.

Fledging occurs at approximately 42 to 46 days of age, though considerable variation exists. Young hawks initially make short flights near the nest, gradually building strength and coordination. The post-fledging dependency period lasts another four to seven weeks, during which parents continue feeding the young while teaching hunting skills through demonstration and gradually reducing food provisioning, forcing the young hawks to practice hunting.

Young hawks disperse from the natal territory by late summer or fall, beginning a nomadic period that may last until they secure their own territories—sometimes not until their second or third year. First-year mortality is high, with only about 50 percent surviving their first year. Those that survive this critical period have good prospects, with wild Red-Tailed Hawks living 10 to 15 years on average. The oldest known wild individual reached at least 30 years, and birds in captivity have survived into their thirties.

Population

The Red-Tailed Hawk enjoys a conservation status of Least Concern according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), reflecting robust and apparently stable populations across its extensive range. This classification marks a conservation success story, particularly given the historical threats that decimated raptor populations during the 20th century.

Global population estimates suggest approximately 2.3 to 3.6 million individual Red-Tailed Hawks, making this one of the most abundant raptors in North America. The species shows a stable or slightly increasing population trend across most of its range, according to data from the North American Breeding Bird Survey and Christmas Bird Counts conducted over several decades.

This positive status represents a remarkable recovery from mid-20th century lows. Like many raptors, Red-Tailed Hawks suffered severe population declines from the 1940s through the 1970s due to widespread use of persistent pesticides, particularly DDT. These chemicals accumulated in the food chain, causing eggshell thinning that led to reproductive failure. The banning of DDT and other persistent organochlorines in the 1970s, combined with legal protections under the Migratory Bird Treaty Act and the recovery of prey populations, enabled hawk populations to rebound dramatically.

The species has also benefited from its remarkable adaptability to human-modified landscapes. Unlike forest-interior specialists that decline with habitat fragmentation, Red-Tailed Hawks have thrived in the mosaic of fields, woodlots, and suburban developments that characterize much of modern North America. Agricultural landscapes, when they include sufficient nesting sites and aren’t intensively managed with heavy pesticide use, can support high hawk densities.

Regional variations exist in population trends. Some localized declines have been noted in areas undergoing intensive urbanization that eliminates both nesting and hunting habitat, while other urban areas have seen population increases as hawks colonize city environments. Western populations may face challenges from climate change-induced alterations in prey populations and habitat conditions.

Continued monitoring is essential, particularly regarding emerging threats like rodenticide poisoning in urban populations and cumulative impacts from wind energy development. However, compared to many raptor species, the Red-Tailed Hawk’s future appears secure, testament to both its behavioral flexibility and the effectiveness of conservation measures enacted over the past half-century.

Conclusion

The Red-Tailed Hawk stands as a testament to nature’s resilience and adaptability. From its commanding presence soaring over prairies to its surprising success in navigating urban jungles, this magnificent raptor has proven that with the right combination of behavioral flexibility and environmental protection, wildlife can not only survive but thrive alongside human civilization. Its recovery from the pesticide crisis of the mid-20th century demonstrates what’s possible when conservation science, policy, and public awareness align.

Yet the Red-Tailed Hawk’s story also reminds us that success is never permanent. Emerging threats like rodenticide poisoning and climate change require our continued vigilance and willingness to adapt our practices to protect these remarkable birds. Every time you spot that russet tail glinting in the sunlight or hear that piercing call echoing across the landscape, you’re witnessing millions of years of evolutionary refinement—a master predator perfectly adapted to its role in the ecosystem. These hawks control rodent populations, maintain ecological balance, and connect us to the wild world that persists around us, even in our most developed landscapes.

The next time you see a Red-Tailed Hawk perched along a highway or soaring over a city park, take a moment to appreciate not just the bird itself, but what it represents: hope that humans and wildlife can coexist, proof that conservation works, and a reminder that we share this world with creatures whose mastery of their domain rivals our own.

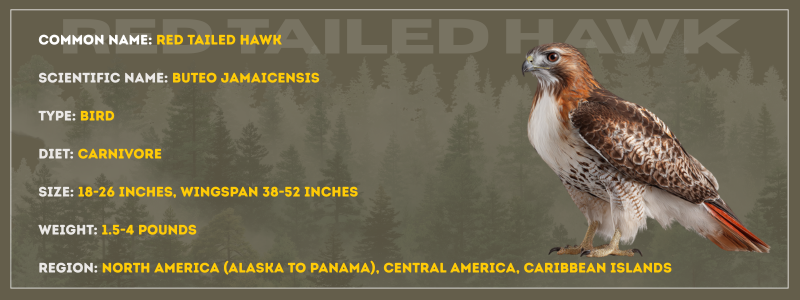

Scientific Name: Buteo jamaicensis

Diet Type: Carnivore

Size: 18-26 inches in length; wingspan 38-52 inches

Weight: 1.5-4 pounds (males smaller, females larger)

Region Found: North America (Alaska to Panama), Central America, Caribbean islands