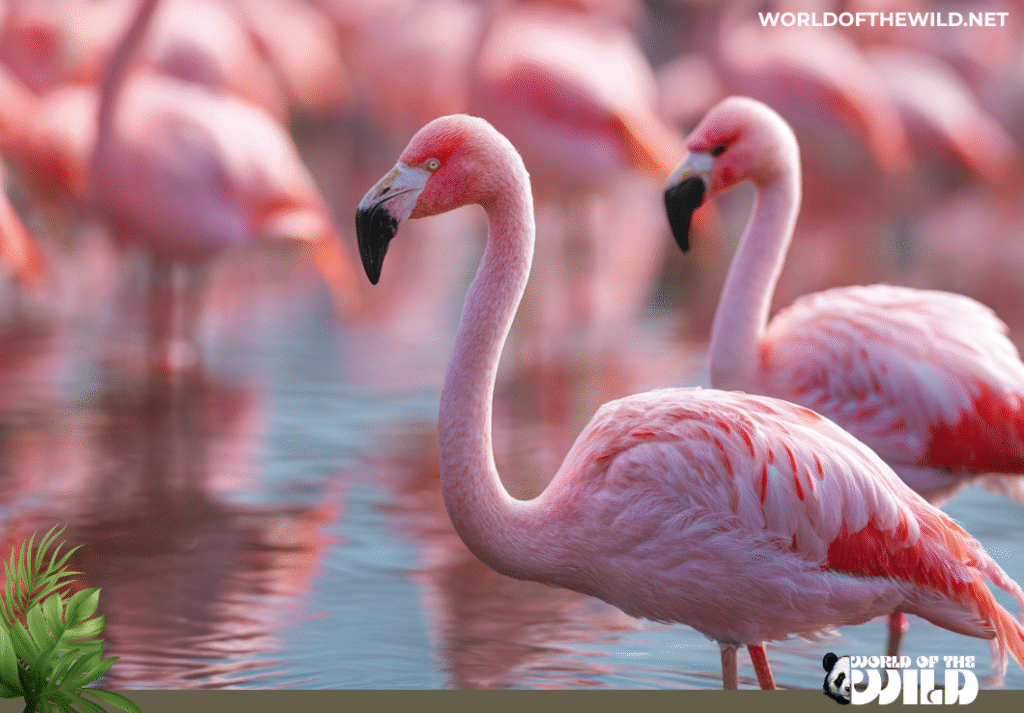

Standing on impossibly thin legs in shallow, shimmering water, flamingos paint lagoons and lakes with strokes of vibrant pink and crimson—a living masterpiece that has captivated human imagination for millennia. These elegant birds, with their distinctive curved bills and synchronized movements, represent one of nature’s most recognizable and beloved creatures. Yet beneath their iconic appearance lies a complex story of evolutionary adaptation, social sophistication, and ecological specialization that makes flamingos far more remarkable than their eye-catching color alone suggests.

Flamingos are wading birds belonging to the family Phoenicopteridae, the sole family in the order Phoenicopteriformes. What makes these birds truly fascinating is their extreme dietary specialization—they are among the most specialized filter-feeding birds on Earth, having evolved a unique feeding system that allows them to thrive in harsh, alkaline environments where few other animals can survive. From the vast colonies numbering in the hundreds of thousands to their mysterious one-legged stance, flamingos embody both grace and resilience in some of the planet’s most challenging ecosystems.

Facts

Here are seven intriguing facts about flamingos that showcase their remarkable nature:

- Ancient Lineage: The oldest flamingo fossils discovered date back approximately 50 million years, making these birds far older than modern humans and demonstrating their evolutionary success.

- Upside-Down Feeders: Flamingos feed with their specially adapted bills held upside-down, using a unique filtering system to separate food from mud and water—a feeding method unlike virtually any other bird species.

- Social Butterflies of the Bird World: Recent research has revealed that flamingos form long-lasting friendships and partnerships that can persist for years, with some birds even avoiding certain flock members they don’t get along with.

- Manufactured Pink: Flamingos aren’t born pink. Young flamingos hatch with grayish-red plumage, acquiring their distinctive pink to red coloration from carotenoids in their diet of algae and invertebrates.

- Salt Water Specialists: Flamingos possess specialized glands beneath their eyes that remove excess salt from their bodies, enabling them to drink saltwater in addition to freshwater.

- Crop Milk Parents: Like pigeons and penguins, both male and female flamingos produce a nutritious secretion called crop milk to feed their young—a relatively rare trait among birds.

- The One-Legged Mystery: While the exact reason remains debated, research on flamingo cadavers has shown that the iconic one-legged stance can be maintained without any muscle activity, while living flamingos demonstrate substantially less body sway when standing on one leg.

Species

Classification

Flamingos occupy their own unique place in the avian world. Their full taxonomic classification is: Kingdom Animalia, Phylum Chordata, Subphylum Vertebrata, Class Aves, Order Phoenicopteriformes, Family Phoenicopteridae.

The taxonomy of flamingos has long puzzled scientists due to their mosaic of characteristics. The skeletal structure, particularly the pelvis and ribs, resembles that of storks, while egg-white proteins are similar to herons, and behavioral patterns, especially in chicks, link them closely to geese. Modern molecular studies have revealed surprising relationships, with flamingos sharing at least 11 morphological traits with grebes, not found in other birds.

The Six Species

The International Ornithological Committee recognizes six flamingo species across three genera: Phoenicopterus, Phoeniconaias, and Phoenicoparrus. These are divided geographically into Old World and New World species.

Old World Species:

- Greater Flamingo (Phoenicopterus roseus): The tallest of all flamingo species, standing 3.9 to 4.7 feet tall and weighing up to 7.7 pounds, with deep pink wings. Found across Africa, southern Europe, the Middle East, and the Indian subcontinent.

- Lesser Flamingo (Phoeniconaias minor): The smallest flamingo species at 2.6 feet tall, weighing about 5.5 pounds. Despite being the smallest, it’s actually the most numerous flamingo species.

New World Species:

- American Flamingo (Phoenicopterus ruber): Also called the Caribbean Flamingo, this species displays the most vibrant coloration. American flamingos are a brighter red color because of the beta carotene availability in their food.

- Chilean Flamingo (Phoenicopterus chilensis): Distinguished by its grayish legs with pink bands at the joints, this species inhabits temperate South America from central Peru to Tierra del Fuego.

- Andean Flamingo (Phoenicoparrus andinus): The only flamingo species with yellow legs and feet, found in the high-altitude salt lakes of the Andes Mountains.

- James’s Flamingo (Phoenicoparrus jamesi): Also called the Puna Flamingo, this species is characterized by having all black flight feathers, including the secondary flight feathers which are red in other species.

Appearance

Flamingos are among the most visually distinctive birds on Earth, instantly recognizable by their unique combination of features. All flamingo species share very long legs, long necks, webbed feet, large wings, and a short tail, with slender bodies ranging from 80 to 160 centimeters in height and 2.5 to 3.5 kilograms in weight.

The most striking feature is undoubtedly their vibrant coloration, which ranges from pale pink to deep crimson depending on species and diet. The pink or reddish color comes from carotenoids in their diet of animal and plant plankton, which are broken down into pigments by liver enzymes. Well-fed, healthy flamingos display more vibrant colors, making plumage brightness an important indicator of fitness to potential mates.

Their most specialized feature is the distinctive curved bill, uniquely adapted for filter feeding. Flamingos can open their bills by raising the upper jaw as well as by dropping the lower jaw, and their bills are adapted to separate mud and silt from the food they eat. The bill is lined with hair-like structures called lamellae that act as filters, while their large, rough tongue helps pump water through the filtering system.

Flamingos have wingspans ranging from as small as 37 inches to as large as 59 inches, with powerful wings that enable them to be strong, capable fliers. Their legs appear to bend backwards while walking, but this is actually an optical illusion—what looks like a backwards-bending knee is actually their ankle, with the true knee hidden within their body plumage.

The neck contains an remarkable 19 vertebrae, providing the flexibility needed for their unique feeding posture. Young flamingos hatch with gray down plumage, which is quickly replaced by a second, darker coat before they develop their adult feathers.

Behavior

Social Structure and Gregariousness

Flamingos are among the most social of all birds, with colony sizes that can number in the hundreds of thousands. These large colonies are believed to serve three purposes: avoiding predators, maximizing food intake, and using scarce suitable nesting sites more efficiently. Recent research has revealed that flamingo societies are far more complex than previously understood. Studies have shown evidence of friendships that persisted through five years of research, with birds forming strong bonds in same-sex and mixed-sex groups of two to four individuals.

Average flock size is roughly 100 birds, though sizes can range from a few individuals to tens of thousands, with small flocks being rare because larger size provides better protection from predators. Within these massive gatherings, flamingos engage in synchronized behaviors, with entire colonies often performing the same activities simultaneously.

Communication and Displays

Flamingos are considered very noisy birds, with vocalizations ranging from grunting or growling to nasal honking that play important roles in parent-chick recognition, ritualized displays, and keeping large flocks together.

Before breeding, colonies split into smaller groups of 15 to 50 birds that perform elaborate synchronized displays. These displays include members standing together, stretching their necks upwards, uttering calls while head-flagging, and then flapping their wings. Specific display behaviors include:

- Head-flagging: Stretching the neck and head up as high as possible with the bill pointing upwards, then rhythmically turning the head from one side to the other

- Wing salute: Wings are spread for a few seconds showing a flash of color, with the neck stretched out and tail flipped up

- Marching: A tight group marches together in one direction, then suddenly flips around and walks the other direction

- Twist-preening: Rapidly alternating between stretching the neck forward and twisting the head around to the back

Daily Activities and Maintenance

Flamingos spend about 15% to 30% of their time during the day preening—a large percentage compared to waterfowl, which preen only about 10% of the time. They have an oil gland near the base of their tail that secretes waterproofing oil, which they distribute throughout their feathers using their bills. Interestingly, Greater Flamingos use uropygial secretions not just for waterproofing but as “make-up” to enhance their feather color.

The young are remarkably precocial and can recognize their parents’ calls from a very early age. After about one week, chicks leave the nesting site and form their own groups called crèches, where they socialize and practice flying together.

Unique Adaptations

The one-legged stance, while iconic, serves practical purposes. Research suggests it helps conserve body heat when standing in cold water and allows one leg to rest—crucial for birds that spend hours wading. The birds’ ability to feed while standing still is an energy-conservation adaptation, requiring less food intake per day than more active feeding methods would demand.

Evolution

The evolutionary history of flamingos is both ancient and fascinating, though some gaps remain in our understanding. Fossils of primitive flamingo forms date back approximately 50 million years, making them one of the oldest bird families. However, the exact evolutionary relationships have long puzzled scientists.

Studies from 2001 determined that the closest living relative of flamingos is the grebe, a surprising discovery given their physical differences. This relationship is supported by molecular evidence and shared morphological traits. Juncitarsus, the ancestor of Mirandornithes (the clade containing both flamingos and grebes), was likely a generalist feeder wading along freshwater lake banks during the early-middle Eocene of Europe and North America.

Flamingos probably diverged from grebes sometime in the late Eocene of Europe, followed quickly by the extinct family Palaelodidae separating from Phoenicopteridae in the latest Eocene. The palaelodids were short-legged, straight-billed flamingo relatives possibly adapted to a swimming and diving lifestyle, quite different from modern flamingos. Palaelodids achieved peak diversity and worldwide distribution around the early Miocene but likely went extinct in the middle Pleistocene.

By the time fossils from modern flamingo family Phoenicopteridae first appear in the late Oligocene, they had already achieved their highly specialized filter-feeding ecology, meaning the earliest evolution of this remarkable feeding system remains unknown. Fossilized flamingo footprints estimated to be seven million years old have been found in the Andes Mountains.

Modern molecular studies place flamingos among the youngest families of birds, counter to classical notions based on biogeography and the fossil record, with living genera diverging from each other less than 4.4 million years ago. The unique curved bill and specialized filtering system likely evolved gradually as dietary preferences changed, allowing flamingos to exploit food sources unavailable to most other birds.

Habitat

Geographic Range

There are four flamingo species distributed throughout the Americas (including the Caribbean), and two species native to Afro-Eurasia. Their distribution spans across multiple continents, from the high-altitude lakes of the South American Andes to the coastal lagoons of Africa, the Mediterranean, the Middle East, and even isolated populations on the Galápagos Islands.

The Old World species—Greater and Lesser Flamingos—inhabit regions across Africa, southern Europe, the Middle East, and the Indian subcontinent. The New World species include the American Flamingo in the Caribbean and northern South America, while the Chilean, Andean, and James’s Flamingos occupy various regions of South America, particularly around the Andes Mountains.

Environmental Requirements

Flamingos are highly specialized for wetland habitats, particularly shallow saline and alkaline lakes, coastal lagoons, salt pans, and estuaries. These environments share specific characteristics crucial to flamingo survival: shallow water (typically less than one meter deep) where they can wade comfortably, high concentrations of their preferred food sources, and suitable mudflats or islands for nesting.

The most extreme flamingo habitats are the alkaline lakes of East Africa and the Andes, where pH levels and mineral concentrations would be toxic to most other animals. These harsh environments have become flamingo refuges precisely because they exclude most predators and competitors. The lakes must maintain specific salinity and alkalinity levels to support the blue-green algae, diatoms, and brine shrimp that form the flamingos’ primary diet.

Many flamingo species are nomadic, moving between different wetlands to track food availability and breeding conditions. They require open, shallow waters for feeding and isolated mudflats or small islands for nesting, providing protection from terrestrial predators. The birds are also highly tolerant of temperature extremes, with Andean species surviving at elevations above 4,000 meters where temperatures can drop below freezing at night.

Diet

Flamingos are omnivores who filter-feed on brine shrimp, cyanobacteria, larvae, insects, mollusks, and crustaceans. Their highly specialized feeding system represents one of the most remarkable adaptations in the avian world.

The feeding process itself is unique among birds. Flamingos’ bills are uniquely used upside-down, with filtering of food assisted by hairy structures called lamellae that line the mandible and their large, rough tongue. When feeding, flamingos wade into shallow water, dip their heads underwater, and turn them upside down so the curved bill can sweep through the water parallel to the bottom. By rapidly retracting their head, flamingos generate vortexes that stir up sediment and shrimp.

Water and food are drawn into the bill, then pumped through the lamellae using a piston-like tongue that can move in and out several times per second. The lamellae act as filters, trapping food particles while allowing water and sediment to flow out the sides of the bill. This efficient system enables flamingos to process large volumes of water while extracting tiny food items.

Different species have slightly different bill structures adapted to different food sizes and feeding depths. Lesser Flamingos have the finest filters and feed primarily on microscopic blue-green algae and diatoms, while species like the Greater Flamingo have coarser filters suited to larger prey items including small crustaceans and mollusks. American Flamingos tend to feed somewhat deeper than other species, often submerging much of their neck.

The carotenoid pigments that give flamingos their characteristic color come directly from their diet, making them literal embodiments of the phrase “you are what you eat.” Birds with better access to carotenoid-rich foods display brighter, more attractive plumage.

Predators and Threats

Natural Predators

Despite their large size and gregarious nature, flamingos face predation at all life stages, though adults benefit from significant protection through flock living. In East Africa, Greater Flamingo eggs and chicks are attacked by Marabou Storks, which can cause complete abandonment of breeding colonies. Lappet-faced Vultures hunt flamingo chicks on land and even pursue fledging flamingos in aerial attacks.

Terrestrial predators include jackals, hyenas, foxes, and wild cats that prey on eggs, chicks, and occasionally adult birds. In Namibia’s Skeleton Coast National Park, Greater Flamingos have been found in the diet of lions that specialized in marine prey. Large birds of prey including eagles occasionally take flamingos, particularly juveniles or sick individuals.

Anthropogenic Threats

Human activities pose far more significant threats to flamingo populations than natural predation. The primary threats include:

Habitat Loss and Degradation: Wetland drainage for agriculture, urban development, and water diversion for human use has destroyed or degraded critical flamingo habitats worldwide. Changes in water management can alter salinity levels, making lakes unsuitable for the specialized algae and invertebrates flamingos depend on.

Climate Change: Rising water levels in East African lakes are reducing salt levels and consequently the amount of prey available to Lesser Flamingos, threatening their feeding and breeding grounds. In the Galápagos, high tides associated with climate change could flood nesting sites, affecting the survival of eggs and chicks. Temperature changes also affect the distribution and abundance of their food sources.

Pollution: Industrial pollutants, agricultural runoff, and heavy metal contamination pose serious threats. Lead poisoning from ingesting spent ammunition in wetlands has caused die-offs. Water hyacinth spread at some sites has reduced available habitat.

Human Disturbance: Tourism, fishing activities, and low-flying aircraft can disturb breeding colonies, causing nest abandonment and reduced reproductive success.

Invasive Species: In the Galápagos, invasive species such as pigs, cats, and dogs attack flamingo eggs and chicks, adding pressure to already small populations.

Direct Exploitation: While historically hunted for their feathers, tongues, and eggs, direct hunting has decreased but still occurs in some regions. In some areas, birds are illegally killed by shooting or trapped to be sold as pets.

Reproduction and Life Cycle

Mating and Nesting

Flamingo reproduction is a highly social affair requiring large colonies to trigger breeding behavior. Before breeding, flamingo colonies split into breeding groups of about 15 to 50 birds, where both males and females perform synchronized ritual displays. These elaborate courtship displays involve the entire group performing coordinated movements including neck stretching, head-flagging, wing displays, and synchronized marching.

Flamingos are monogamous within a breeding season and often maintain pair bonds across multiple years. Both partners participate equally in selecting nest sites and construction. Nests are typically truncated mud cones built on mudflats, with a shallow bowl at the top. On rocky, mudless islands like those in the Galápagos, nests are small piles of stones and debris. Nests are built surprisingly close together in dense colonies, sometimes with only centimeters separating them.

Eggs and Incubation

The clutch consists of one egg, rarely two, with an incubation period of 27–31 days. Both parents share incubation duties equally. The single-egg strategy is common among birds with long lifespans and reflects the significant parental investment required.

Chick Development

Chicks hatch with pale gray down, which is quickly replaced by a second darker coat. Unlike their colorful parents, young flamingos are gray for their first one to three years. The chicks are semi-precocial and can leave the nest within days of hatching.

A remarkable aspect of flamingo parenting is the production of crop milk—a highly nutritious secretion produced in the upper digestive tract by both males and females. This pink or red liquid is rich in fats and proteins and provides essential nutrition during the chicks’ early development. The color comes from carotenoids and may actually help kickstart the development of the young birds’ pink coloration.

After about a week, chicks form crèches—large groups of young flamingos supervised by a few adults while parents forage. Within these groups, chicks can recognize the sounds of their parents from a very early age, allowing for communication and feeding of their own offspring within the crowded crèche.

Fledging and Maturation

Fledging occurs at 65–90 days, when young flamingos develop their flight feathers and begin making their first flights. However, they don’t reach sexual maturity or acquire their full adult plumage for several years—typically 3 to 6 years depending on species.

Lifespan

Flamingos are notably long-lived birds. In the wild, they commonly live 20 to 30 years, with some individuals reaching 40 years or more. In captivity, where they face fewer predators and receive veterinary care, flamingos can live even longer, with several documented cases of birds surviving beyond 50 years. This longevity, combined with their delayed sexual maturity and single-egg clutches, means that flamingo populations recover slowly from declines.

Population

Conservation Status

The conservation status varies significantly among the six flamingo species. The Caribbean (American) and Greater Flamingos are listed as “Least Concern” by the IUCN, while the Lesser, James’s, and Chilean Flamingos are listed as “Near Threatened,” and the Andean Flamingo is listed as “Vulnerable”.

Four of the six flamingo species are of conservation importance, with three species showing declining population trends currently. The different statuses reflect varying degrees of threat from habitat loss, human disturbance, and climate change.

Population Estimates

Current global population estimates vary by species:

- Greater Flamingo: Several hundred thousand individuals across Africa, Europe, and Asia, with stable or increasing populations in some regions

- American Flamingo: Over 200,000 birds globally, including 129,000–217,000 in the Bahamas/Cuba, 40,000 in Mexico, 50,000 in the southern Caribbean, and 490 in the Galápagos Islands

- Lesser Flamingo: The most numerous species with populations potentially exceeding 2 million, though the species is currently considered Near Threatened due to habitat changes threatening its specialized food sources

- Chilean Flamingo: An estimated 200,000 individuals with a declining trend

- Andean Flamingo: Approximately 34,000 individuals, making it the rarest flamingo species

- James’s Flamingo: Around 64,000 individuals, with a particularly interesting history—thought extinct in 1924, a population was rediscovered in 1957

Population Trends

Population trends for Andean, Lesser, James’s, and Chilean Flamingos are decreasing, while trends for Greater and American Flamingos are increasing. The improving status of some species reflects successful conservation efforts, particularly protection of key breeding sites and wetland conservation initiatives.

The American Flamingo has shown marked recovery since the 1990s, when the global population was estimated at only about half its current size. This recovery demonstrates that targeted conservation efforts can be effective when implemented properly.

However, the overall picture remains concerning for several species. The concentration of populations at a limited number of breeding sites makes flamingos particularly vulnerable to catastrophic events or habitat changes at these critical locations.

Conclusion

Flamingos stand as remarkable testaments to the power of evolutionary adaptation and ecological specialization. From their 50-million-year history to their complex social bonds, from their unique upside-down feeding to their vibrant carotenoid-based coloration, these birds embody nature’s creativity and resilience. Their ability to thrive in some of Earth’s most extreme environments—alkaline lakes that would burn human skin—speaks to their remarkable physiological adaptations.

Yet for all their evolutionary success, flamingos now face unprecedented challenges from human activities. The loss and degradation of wetland habitats, compounded by climate change and pollution, threaten populations that took millions of years to evolve. The varying conservation statuses across species—from Least Concern to Vulnerable—remind us that survival is never guaranteed, even for iconic species.

The silver lining is that flamingo conservation efforts have proven successful where implemented. The recovery of American Flamingo populations and the rediscovery of James’s Flamingo after being presumed extinct demonstrate that targeted action makes a difference. Protecting critical wetland habitats, managing water resources sustainably, and addressing climate change aren’t just environmental priorities—they’re essential for preserving these magnificent birds and the fragile ecosystems they inhabit.

As we move forward, flamingos can serve as ambassadors for wetland conservation. Their beauty captures public attention, but their ecological importance runs far deeper. They serve as indicators of wetland health, their presence signaling productive, functioning ecosystems. By protecting flamingos and their habitats, we safeguard countless other species that depend on these same wetlands.

The story of flamingos is still being written. Whether future chapters tell of recovery and resilience or decline and loss depends on choices made today. Supporting wetland conservation, advocating for climate action, and raising awareness about these remarkable birds are concrete steps each person can take. After 50 million years of evolutionary success, flamingos deserve our commitment to ensuring they grace our planet for millions more.