Imagine a creature so vibrantly colored it looks like it was painted by an artist with an unlimited palette, so bizarrely shaped it could have crawled out of a fever dream, and so delicate it seems impossible that it survives in the wild ocean. Meet the nudibranch—a sea slug that has abandoned its shell and transformed into one of the ocean’s most spectacular and diverse inhabitants. These extraordinary mollusks glide across coral reefs and rocky substrates like underwater butterflies, their frilled appendages and psychedelic patterns making them favorites among divers and marine photographers worldwide. Far from being merely beautiful, nudibranchs are fascinating examples of evolutionary innovation, employing chemical warfare, borrowed weapons, and remarkable regenerative abilities to thrive in oceans around the globe.

Facts

- Stolen Weaponry: Many nudibranchs consume stinging cells (nematocysts) from their prey—such as jellyfish and anemones—without triggering them, then transport these weapons to specialized sacs in their skin where they’re repurposed for their own defense.

- Solar-Powered Sea Slugs: Some species in the related sacoglossan group can incorporate chloroplasts from algae into their tissues and photosynthesize, though true nudibranchs themselves don’t possess this ability.

- Chemical Alchemists: Nudibranchs can synthesize toxic compounds from their food or produce their own chemical defenses, advertising their toxicity through brilliant warning colors—a phenomenon known as aposematism.

- Hermaphroditic Reproducers: Every nudibranch is both male and female simultaneously, and when two individuals mate, they typically fertilize each other in a reciprocal exchange.

- Disposable Body Parts: Some species can shed and regenerate their cerata (finger-like appendages) when threatened, leaving predators with a mouthful of toxic tissue while they escape.

- Short but Productive Lives: Most nudibranch species live only a few months to a year, but during this brief existence, a single individual can lay hundreds of thousands or even millions of eggs.

- Sensory Specialists: The rhinophores (horn-like structures on their heads) are chemosensory organs that “taste” the water, allowing nudibranchs to detect food, mates, and danger with remarkable precision.

Species

Kingdom: Animalia

Phylum: Mollusca

Class: Gastropoda

Order: Nudibranchia

Family: Multiple (over 100 families)

Genus: Multiple (over 3,000 species across numerous genera)

Species: Varies by specific type

The order Nudibranchia encompasses over 3,000 described species, making it one of the most diverse groups of marine gastropods. The order is divided into two main suborders: Doridina and Cladobranchia. Doridina, commonly called dorid nudibranchs, typically have a circular plume of gills on their backs and include families like Chromodorididae, known for their spectacular color patterns. Cladobranchia includes the aeolid nudibranchs (suborder Aeolidida), which sport numerous cerata along their backs that contain branches of their digestive systems and sometimes stolen nematocysts.

Some notable species include the Spanish shawl (Flabellina iodinea), adorned in brilliant purple with orange cerata; the blue dragon (Glaucus atlanticus), a pelagic species that floats upside-down at the ocean’s surface; and the lettuce sea slug (Elysia crispata), though technically not a true nudibranch but a closely related sacoglossan. Each species has evolved unique adaptations to its particular ecological niche, from the deep sea to tropical reefs.

Appearance

Nudibranchs are soft-bodied mollusks that have lost their shells entirely during evolution, leaving them completely exposed. Their sizes range dramatically from a few millimeters to over 12 inches in length, with most species falling between one and three inches. The Spanish dancer (Hexabranchus sanguineus) stands out as one of the largest, occasionally reaching lengths of 16 inches.

Their most striking feature is undoubtedly their coloration. Nudibranchs display virtually every color imaginable—electric blues, neon pinks, deep purples, brilliant oranges, and stark blacks and whites, often in wild combinations and intricate patterns. These colors serve multiple purposes: warning predators of toxicity, camouflaging against colorful substrates, or helping individuals recognize their own species.

The body plan varies considerably between groups. Dorid nudibranchs typically have smooth, rounded bodies with a rosette of retractable gills (the branchial plume) positioned on their backs near the rear. Aeolid nudibranchs sport numerous finger-like projections called cerata arranged along their backs in rows. All nudibranchs possess two rhinophores on their heads—club-shaped or feathery sensory organs that emerge from the anterior portion of the body. Most species also have a simple foot for gliding across surfaces and tentacle-like oral structures near their mouths.

Their skin can be smooth, warty, or covered with various appendages, and many species incorporate crystalline structures or tubercles that add texture and dimension to their appearance. There are no scales, fur, or hard parts—just delicate, permeable skin that exchanges gases directly with the surrounding water.

Behavior

Nudibranchs are generally solitary creatures, though they may aggregate when food sources are abundant or during spawning events. They move slowly across substrates using a muscular foot that secretes mucus, gliding at speeds that would make a garden snail look like a racecar. Despite their leisurely pace, they’re active hunters or grazers, constantly searching for food using their highly developed chemosensory abilities.

Communication in nudibranchs occurs primarily through chemical signals. They leave pheromone trails in their mucus that other individuals can detect and follow, particularly important during mating season. The rhinophores constantly sample the water, detecting dissolved chemicals that convey information about food, potential mates, and environmental conditions.

When threatened, different species employ various defensive strategies. Some curl into tight balls, protecting their vulnerable underside. Others release toxic or distasteful compounds into the water. Certain species autotomize their cerata, deliberately dropping these appendages which continue to writhe and release deterrent chemicals while the nudibranch escapes. The sheer brightness of their coloration serves as a constant warning to potential predators: “I’m toxic—don’t eat me.”

Some species exhibit fascinating specialized behaviors. The Spanish dancer performs a distinctive undulating swimming motion when disturbed, flaring its bright red mantle in a display reminiscent of a flamenco dancer’s dress. Certain nudibranchs demonstrate surprising site fidelity, returning to the same resting spots after foraging expeditions.

While not possessing complex brains, nudibranchs show basic learning capabilities and can remember locations of food sources and navigate relatively complex terrain. Their nervous systems, though simple, effectively coordinate their hunting, defensive, and reproductive behaviors.

Evolution

Nudibranchs belong to the class Gastropoda, which emerged during the Cambrian period approximately 500 million years ago. However, nudibranchs themselves are relative newcomers to the evolutionary stage, with fossil evidence suggesting they diverged from shelled gastropods during the late Carboniferous or early Permian periods, roughly 300 million years ago.

The defining evolutionary event in nudibranch history was the loss of the protective shell that characterizes most mollusks. This dramatic change occurred as ancestral gastropods increasingly relied on chemical defenses rather than physical armor for protection. As toxic compounds accumulated in their tissues—either produced metabolically or sequestered from prey—the energetic cost of maintaining a heavy shell became unnecessary. Natural selection favored individuals that redirected that energy toward reproduction and growth.

The evolution of specialized structures followed shell loss. The external gills evolved to replace the mantle cavity that shells once protected. The rhinophores became increasingly sophisticated chemosensory organs. Perhaps most remarkably, some lineages evolved the ability to sequester and utilize the defensive mechanisms of their prey—an evolutionary innovation called kleptocnidy (stealing stinging cells) that appeared multiple times independently in nudibranch evolution.

The incredible diversity of nudibranch species represents an adaptive radiation that accelerated during the Cenozoic era as coral reefs expanded and diversified, providing an abundance of ecological niches. Different lineages specialized on different prey items—hydroids, sponges, bryozoans, tunicates, anemones—and their body forms, colors, and chemical defenses co-evolved with their specific food sources.

Habitat

Nudibranchs inhabit oceans worldwide, from polar waters to tropical seas, though diversity peaks in warm, shallow tropical and subtropical regions, particularly in the Indo-Pacific. They occupy various marine environments from the intertidal zone down to depths exceeding 2,000 feet, though most species prefer shallower waters between 30 and 150 feet deep.

Their preferred habitats include coral reefs, rocky reefs, kelp forests, seagrass beds, and muddy or sandy bottoms. Coral reefs support the highest diversity, offering abundant food sources and complex three-dimensional structures for shelter and hunting. Rocky substrates covered with sponges, hydroids, and other sessile invertebrates provide rich feeding grounds for many species.

Different species show remarkable habitat specificity, often tied directly to their specialized diets. A nudibranch that feeds exclusively on a particular sponge species will only be found where that sponge occurs. This specialization means individual nudibranch species may have limited ranges, though the group as a whole is cosmopolitan.

Some species, like the blue dragon, have adopted a pelagic lifestyle, floating in open ocean waters far from shore. These drifters ride ocean currents and hunt other pelagic organisms like Portuguese man o’ wars. Most nudibranchs, however, are benthic, living their entire lives crawling across the seafloor or reef structures.

Temperature, salinity, and water quality influence nudibranch distribution. Many species are sensitive to environmental changes and thrive only within specific parameter ranges. Tropical species require warm, stable temperatures, while cold-water species from polar regions have adapted to near-freezing conditions.

Diet

Nudibranchs are carnivorous, though their prey items are typically sessile or slow-moving invertebrates rather than active animals. Each species usually specializes on a narrow range of prey, and their diet directly influences their coloration, chemical defenses, and even body shape.

Dorid nudibranchs commonly feed on sponges, using their radula—a ribbon-like feeding organ covered with tiny teeth—to rasp away tissue. Different species target specific sponge species, and many incorporate the sponge’s chemical defenses into their own tissues. Some dorids also consume bryozoans (moss animals), tunicates (sea squirts), and other encrusting organisms.

Aeolid nudibranchs predominantly feed on cnidarians, including hydroids, anemones, corals, and even jellyfish. They use their radula to pierce through tissues and consume the prey’s cells, carefully avoiding triggering the nematocysts (stinging cells), which they transport to their cerata for later use in their own defense. This remarkable process involves specialized cells called cnidosacs that store the unfired nematocysts.

Some specialized species have evolved to eat other mollusks, including other nudibranchs, engaging in cannibalism or inter-species predation. A few species feed on fish eggs, worms, or other soft-bodied invertebrates.

Nudibranchs locate food primarily through chemoreception. Their rhinophores detect dissolved chemicals released by potential prey, allowing them to track food sources across considerable distances. Once they locate prey, they may spend hours or days feeding in one spot before moving on, completely consuming colonial organisms or taking bites from larger prey.

Predators and Threats

Despite their toxic defenses and warning coloration, nudibranchs do face predation. Their natural predators include certain fish species that have evolved resistance to their toxins, such as some wrasses and pufferfish. Sea spiders (pycnogonids) prey on nudibranchs, piercing their bodies and sucking out fluids. Some sea slugs cannibalize other nudibranch species, and certain crustaceans opportunistically consume them.

However, the brilliant colors that warn most predators away are highly effective, meaning predation rates remain relatively low compared to undefended organisms. The most significant natural threat comes from specialized predators that have evolved alongside nudibranchs and developed tolerance to their specific toxins.

Anthropogenic threats pose increasingly serious challenges. Habitat degradation from coastal development, destructive fishing practices, and pollution directly impact nudibranch populations by destroying the complex reef and benthic habitats they require. Since many species depend on specific prey organisms, anything that harms those prey populations—including sponge diseases or hydroid die-offs—indirectly threatens nudibranchs.

Ocean acidification presents a particularly insidious threat. While nudibranchs lack shells themselves, their prey items often include calcifying organisms like certain sponges and corals. Acidification that reduces these prey populations will cascade through the ecosystem to affect nudibranch abundance and diversity.

Climate change impacts nudibranchs through multiple pathways: rising ocean temperatures can exceed the thermal tolerance ranges of temperature-sensitive species, while changing ocean chemistry and warming waters facilitate the spread of diseases and invasive species that disrupt established ecological relationships.

Marine pollution, including plastics, heavy metals, and agricultural runoff, degrades water quality and can bioaccumulate in nudibranch tissues. Their permeable skin makes them particularly vulnerable to dissolved pollutants.

Collection for the aquarium trade affects some particularly colorful species, though nudibranchs generally fare poorly in captivity due to their specialized dietary requirements.

Reproduction and Life Cycle

Nudibranchs are simultaneous hermaphrodites, possessing both male and female reproductive organs, though they cannot self-fertilize and must find a partner. When two individuals meet, they often engage in elaborate courtship behaviors involving chemical signaling, circling, and gentle touching with their oral tentacles and rhinophores.

During mating, the two nudibranchs align themselves head-to-tail or side-by-side, allowing their genital openings (located on the right side of their bodies) to connect. They simultaneously exchange sperm in a reciprocal copulation that can last from a few minutes to several hours. Both individuals store the received sperm and will later use it to fertilize their own eggs.

After mating, nudibranchs lay eggs in distinctive ribbons, coils, or rosettes attached to substrates. The egg masses can contain anywhere from a few hundred to several million eggs, depending on the species and the individual’s size. These egg clusters are often beautifully colored—white, yellow, pink, or orange—and may be arranged in elegant spiral patterns. The eggs contain toxins sequestered from the parent’s diet, protecting them from predation.

Development occurs within the egg case over a period of days to weeks. Most species hatch as free-swimming veliger larvae equipped with tiny shells and ciliated lobes for swimming. These planktonic larvae drift in ocean currents, feeding on microscopic organisms, and may travel considerable distances before settling. Upon settlement, they undergo metamorphosis, losing their larval shell and transforming into miniature versions of adults.

Some species exhibit direct development, hatching as crawling juveniles without a planktonic stage. This strategy reduces dispersal but increases survival rates since the vulnerable larval period in open water is eliminated.

Nudibranchs grow quickly, reaching sexual maturity in weeks to months. Their lifespan varies by species but generally ranges from a few months to slightly over a year. Most species are semelparous, reproducing intensively once or a few times before dying, though some can reproduce multiple times if food is abundant. The combination of short lifespans and high reproductive output allows populations to respond quickly to environmental changes.

Population

Due to the immense diversity of nudibranch species and their often cryptic nature, comprehensive population assessments are challenging. The conservation status varies dramatically by species. Most nudibranch species have not been individually evaluated by the IUCN Red List, and many species likely remain undescribed by science.

Generally, common and widespread species that tolerate various habitats and feed on abundant prey maintain stable populations and would likely qualify as Least Concern if assessed. However, species with highly restricted ranges, extreme habitat specialization, or dependence on threatened ecosystems face greater vulnerability.

No nudibranch species are currently listed as Endangered or Critically Endangered at the global level, partly due to insufficient data rather than confirmed security. Some endemic species confined to small geographic areas or specific island systems could be at risk from localized threats, but comprehensive assessments are lacking.

Population trends mirror the health of marine ecosystems generally. In regions where coral reefs are degrading or coastal development is intense, nudibranch diversity and abundance are declining. Conversely, well-protected marine reserves often support robust nudibranch populations with high species richness.

Global population estimates are impossible to provide given the taxonomic diversity—attempting to count all nudibranchs would be like trying to count all butterflies. Individual species populations likely range from thousands to millions of individuals, depending on their range, habitat availability, and reproductive success.

The greatest concern is not extinction of common species but rather the loss of undiscovered diversity and the ecosystem-level effects of declining marine habitat quality. As reef systems degrade globally, the specialized ecological relationships that nudibranchs depend upon are disrupted, potentially driving population declines before species are even scientifically described.

Conclusion

Nudibranchs stand as testament to evolution’s creative power, transforming vulnerable shell-less mollusks into some of the ocean’s most spectacular and chemically sophisticated creatures. Their dazzling colors and bizarre forms have captured human imagination, making them ambassadors for the often-overlooked invertebrate world. Yet beyond their aesthetic appeal, these sea slugs play important ecological roles as predators of sessile invertebrates and as prey for specialized predators, participating in complex food webs and chemical arms races that shape reef ecosystems.

The future of nudibranchs is inextricably linked to the health of our oceans. As climate change, pollution, and habitat destruction accelerate, these sensitive creatures serve as living indicators of marine ecosystem integrity. Protecting nudibranchs means protecting the coral reefs, rocky shores, and diverse marine habitats they call home. By supporting marine conservation efforts, reducing our carbon footprint, and advocating for ocean protection policies, we can help ensure that these living kaleidoscopes continue to grace our planet’s seas—reminding us that some of nature’s most extraordinary artistry happens beneath the waves, where beauty and biochemical warfare combine in creatures small enough to fit in the palm of your hand.

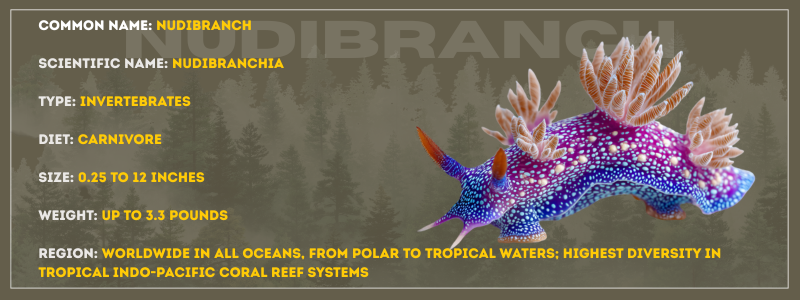

Scientific Name: Order Nudibranchia (over 3,000 species across multiple families and genera)

Diet Type: Carnivorous (specialized predators of sponges, cnidarians, bryozoans, tunicates, and other invertebrates)

Size: 0.16 inches to 16 inches (4 mm to 40 cm), most species 0.4–3 inches (1–8 cm)

Weight: Less than 0.04 ounces to approximately 3.5 ounces (less than 1 gram to 100 grams), varies greatly by species

Region Found: Worldwide in all oceans, from polar to tropical waters; highest diversity in tropical Indo-Pacific coral reef systems