Picture a flash of brilliant red against a backdrop of winter snow, accompanied by a clear, whistling song that seems to pierce the cold morning air. This is the Northern Cardinal, one of North America’s most beloved and recognizable birds. Unlike many songbirds that flee south when temperatures drop, the cardinal remains a year-round resident, bringing color and music to backyards and woodlands through even the harshest winters. This striking bird has captured the hearts of millions, becoming the official state bird of seven U.S. states—more than any other species. Beyond its stunning appearance, the Northern Cardinal offers a fascinating window into avian behavior, adaptation, and the intricate relationships between wildlife and human-modified landscapes.

Facts

- Female cardinals sing too: Unlike most songbird species where only males vocalize, female Northern Cardinals are accomplished singers who use their songs to communicate with their mates and defend territory.

- They’re not naturally bald: Occasionally, cardinals are spotted completely bald, a temporary condition caused by mite infestations or abnormal molting patterns that resolves when new feathers grow back.

- Their red color comes from food: Cardinals cannot produce red pigments on their own; instead, they derive carotenoids from the fruits and berries they eat, which are then deposited in their feathers during molting.

- They’ve been expanding northward: Over the past century, Northern Cardinals have significantly extended their range into Canada, likely due to a combination of climate change, increased ornamental plantings, and widespread bird feeding.

- Cardinals can live surprisingly long: While most wild cardinals live 3-5 years, the oldest recorded Northern Cardinal survived to at least 15 years and 9 months in the wild.

- They’re aggressive defenders: Despite their cheerful appearance, cardinals are fiercely territorial and have been known to attack their own reflections in windows, car mirrors, and hubcaps for hours or even weeks during breeding season.

- Their crest reveals their mood: The distinctive head crest isn’t just decorative—cardinals raise and lower it to communicate aggression, alarm, or courtship intentions to other birds.

Sounds of the Northern Cardinal

Species

The Northern Cardinal belongs to the following taxonomic classification:

- Kingdom: Animalia

- Phylum: Chordata

- Class: Aves

- Order: Passeriformes

- Family: Cardinalidae

- Genus: Cardinalis

- Species: Cardinalis cardinalis

Within the species Cardinalis cardinalis, scientists recognize approximately 19 subspecies that vary primarily in size and the intensity of plumage coloration. These subspecies are distributed across the bird’s extensive range from southern Canada through Mexico and into Central America. The nominate subspecies, C. c. cardinalis, is found in the eastern United States. Notable subspecies include C. c. superbus of the southwestern United States, which tends to be slightly larger and paler, and C. c. carneus of the Yucatan Peninsula, which displays the most vibrant red coloration.

The genus Cardinalis contains two other species: the Pyrrhuloxia (Cardinalis sinuatus), sometimes called the desert cardinal, found in the southwestern United States and Mexico, and the Vermilion Cardinal (Cardinalis phoeniceus), a critically endangered species endemic to Colombia and Venezuela.

Appearance

The Northern Cardinal is a mid-sized songbird measuring 8 to 9 inches in length with a wingspan of 10 to 12 inches. Adults typically weigh between 1.5 and 1.7 ounces, making them slightly larger and stockier than many common backyard birds.

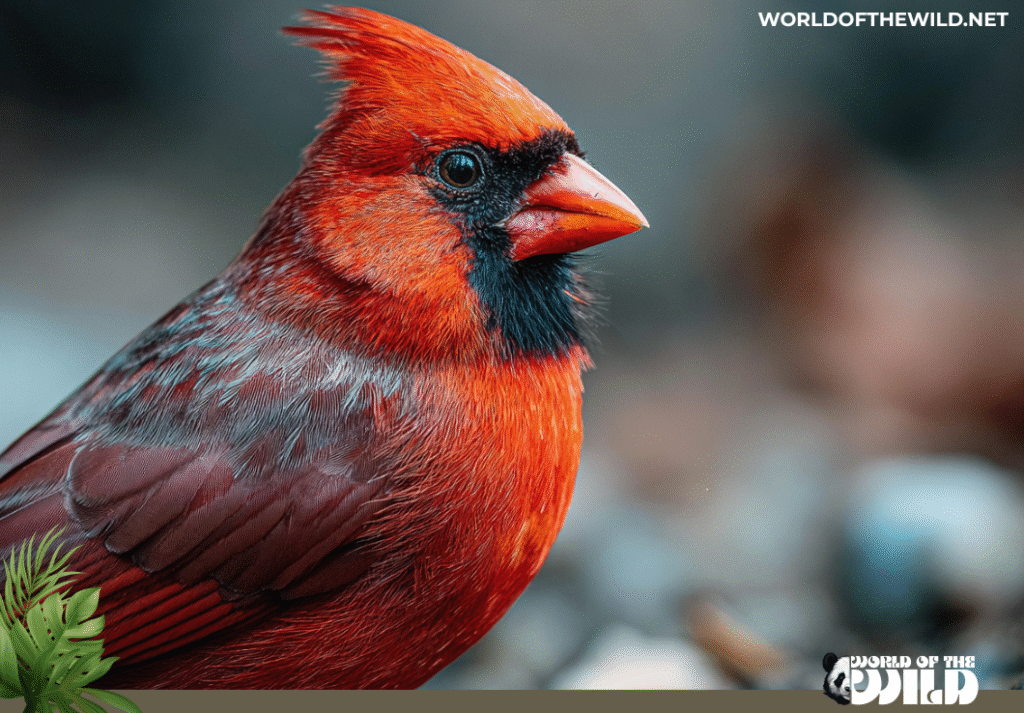

Male cardinals are unmistakable with their brilliant red plumage that covers nearly their entire body. Their faces feature a distinctive black mask that extends from the base of their stout, conical orange-red bill around their eyes and down to their upper throat. This mask creates a striking contrast against the crimson feathers. Males also sport a prominent crest on their heads that can be raised or lowered depending on their emotional state.

Female cardinals, while less flamboyant, possess their own subtle beauty. Their plumage is primarily warm brown or olive-buff with reddish tinges on their wings, tail, and crest. They share the male’s distinctive crest and stout bill, though their bills tend to be slightly duller orange. Females also have the black or grayish facial markings, though these are less pronounced than in males. This more subdued coloration provides excellent camouflage when sitting on nests.

Juvenile cardinals of both sexes resemble adult females but appear even duller, with dark gray or blackish bills that gradually transition to the adult orange-red color over their first few months of life. Young males begin showing patches of red feathers during their first molt, creating a mottled appearance before they achieve their full adult plumage.

The cardinal’s most recognizable feature beyond color is its robust, cone-shaped bill, perfectly adapted for cracking seeds and nuts. Their legs and feet are dark gray or brown, equipped with strong toes for perching and hopping along the ground.

Behavior

Northern Cardinals are primarily diurnal birds most active during early morning and late afternoon hours. Unlike many songbirds that forage high in tree canopies, cardinals spend considerable time on or near the ground, hopping through underbrush and leaf litter in search of food. They move with a distinctive hopping motion, often with their tails raised.

These birds maintain strong pair bonds that often last multiple breeding seasons or even for life. Both members of a pair remain in close contact throughout the year, frequently seen foraging together even outside the breeding season. Cardinals communicate through a variety of calls and songs, with both sexes being vocal. Males sing to establish and defend territories, producing loud, clear whistles that sound like “birdy-birdy-birdy” or “cheer-cheer-cheer.” Females answer with similar but slightly softer songs, and mated pairs often engage in duet singing, with the female’s response coming so quickly after the male’s song that they sound like a single bird.

Cardinals are notably aggressive when defending their territories, which typically range from 2 to 10 acres depending on habitat quality. Males will chase intruding cardinals and even attack their own reflections, perceiving them as rivals. This territorial behavior is most intense during breeding season but continues year-round in many populations.

One charming courtship behavior involves “mate feeding,” where the male collects food items and passes them to the female in a brief, tender moment that resembles a kiss. This behavior strengthens pair bonds and may help the female assess the male’s ability to provide for future offspring.

Cardinals are non-migratory birds that remain in their territories throughout the year. During harsh winter weather, they may join mixed-species flocks at rich food sources but generally maintain their territorial boundaries. At night, they roost in dense shrubs or evergreens, often returning to the same roosting sites repeatedly.

Their intelligence manifests in problem-solving abilities at feeders and learned behaviors. Cardinals quickly adapt to various feeder types and can learn to exploit new food sources. They’ve also demonstrated the ability to recognize individual humans who regularly provide food.

Evolution

The evolutionary history of the Northern Cardinal traces back to the broader radiation of the family Cardinalidae, which diverged from other New World songbirds approximately 20 million years ago during the Miocene epoch. The Cardinalidae family evolved in the Americas and includes other species such as grosbeaks, buntings, and tanagers.

The genus Cardinalis likely originated in Central America or Mexico, where the greatest diversity of related species exists today. Fossil evidence of cardinal-like birds is limited due to the fragile nature of avian bones, but molecular genetic studies suggest that the Northern Cardinal as a distinct species emerged within the last 1-2 million years, during the Pleistocene epoch.

The species’ distinctive features—particularly the robust seed-crushing bill and vibrant carotenoid-based plumage—evolved as adaptations to their ecological niche. The powerful bill represents convergent evolution with other seed-eating birds, allowing efficient exploitation of various seed types. The red coloration in males likely evolved through sexual selection, as females show preferences for more brightly colored mates, which may signal superior foraging abilities and genetic quality.

During the Pleistocene glacial cycles, cardinal populations were likely fragmented into multiple refugia in the southern United States and Mexico. As glaciers retreated and climates warmed, cardinals expanded northward, colonizing new territories. This expansion continues today, with cardinals reaching further into Canada than historical records indicate, representing ongoing evolutionary adaptation to temperate climates.

The evolution of year-round territoriality and non-migratory behavior sets cardinals apart from many temperate songbirds and represents a significant ecological strategy. This adaptation required physiological changes allowing survival through cold winters, including the ability to fluff feathers for insulation and metabolic adjustments to maintain body temperature.

Habitat

The Northern Cardinal inhabits a vast geographic range extending from southeastern Canada through the eastern and central United States, into Mexico, and south through Central America to northern Guatemala and Belize. The species has shown remarkable range expansion over the past 150 years, moving significantly northward and westward from its historical core range in the southeastern United States.

Cardinals thrive in woodland edges, thickets, and areas with dense shrubby undergrowth rather than deep forest interiors. They show a strong preference for habitat mosaics that combine trees for nesting and singing perches with dense shrubs for cover and ground areas for foraging. This preference makes them exceptionally well-adapted to human-modified landscapes, including suburban gardens, parks, and residential areas with ornamental plantings.

Within their preferred habitats, cardinals seek out areas with layered vegetation structure. They favor locations with plants that provide both food and shelter, particularly dense tangles of shrubs between three and ten feet high. Native plant species like dogwood, sumac, wild grape, and various berry-producing shrubs are especially important. Cardinals also utilize coniferous trees like spruce and pine for winter roosting sites and shelter during storms.

The species demonstrates remarkable adaptability to elevation, occurring from sea level to approximately 7,000 feet in mountainous regions. In their southern range, cardinals inhabit both humid tropical forests and semi-arid scrublands, though they always require some access to denser vegetation.

Water sources are important habitat components, and cardinals are frequently found near streams, ponds, or other water bodies where they can drink and bathe. They are particularly fond of shallow water for bathing and will visit bird baths regularly.

Their successful adaptation to suburban and urban environments has actually increased cardinal populations in many regions. The combination of bird feeders providing supplemental food, ornamental plantings offering nest sites, and reduced natural predators in developed areas has allowed cardinals to thrive alongside humans in ways that benefit the species.

Diet

The Northern Cardinal is an omnivore with seasonal dietary variations, though seeds and grains form the foundation of its nutrition throughout most of the year. Their powerful, conical bills are specifically adapted for crushing hard seeds, and they employ a specialized technique where they use their tongues to manipulate seeds against the ridged upper bill while the lower mandible cracks the shell.

During spring and summer, approximately 30% of the adult cardinal’s diet consists of insects and other invertebrates, including beetles, cicadas, grasshoppers, caterpillars, flies, and spiders. This protein-rich food becomes especially important during breeding season. Cardinals feed their nestlings almost exclusively on insects for the first few days of life, gradually introducing seeds as the chicks grow.

The primary seed sources include sunflower seeds, safflower seeds, white millet, and various grass seeds. In natural settings, cardinals consume seeds from native plants such as smartweed, ragweed, sedges, and foxtail grass. They also feed on tree seeds including maple, elm, and tulip tree.

Fruits and berries constitute another important dietary component, particularly in late summer and fall. Cardinals eat mulberries, dogwood berries, wild grapes, blackberries, sumac fruits, and the fruits of various native plants. The carotenoid pigments in many of these fruits directly contribute to the vibrant red coloration in male plumage.

Cardinals are ground foragers who use a distinctive “double-scratch” technique, hopping forward and rapidly kicking both feet backward simultaneously to uncover hidden seeds in leaf litter. They also glean insects from foliage and bark, and will occasionally hover briefly to snatch insects or berries from branch tips.

At bird feeders, cardinals show preferences for platform feeders or hopper feeders where they can perch comfortably. They are among the first birds to visit feeders at dawn and often the last to feed before dusk, a behavior pattern that reduces competition with more aggressive daytime feeders.

Predators and Threats

Northern Cardinals face predation pressure from various animals throughout their range. Natural predators include hawks, particularly Cooper’s Hawks and Sharp-shinned Hawks, which specialize in hunting birds. Domestic and feral cats represent one of the most significant predation threats, especially in suburban environments where cardinals frequently nest at low heights. Snakes, including rat snakes and black racers, raid cardinal nests to consume eggs and nestlings. Other nest predators include blue jays, grackles, squirrels, and chipmunks.

Adult cardinals are vulnerable to larger predators as well. Owls hunt cardinals at their nighttime roosts, while shrikes occasionally capture cardinals in open areas. During ground foraging, cardinals must remain vigilant for terrestrial predators like foxes, raccoons, and opossums, though these mammals more commonly threaten nests than adult birds.

Human-caused threats present growing challenges despite the species’ overall population stability. Window collisions kill significant numbers of cardinals annually, as their territorial aggression toward their own reflections leads them to repeatedly strike glass surfaces. Pesticide use reduces insect prey populations essential for breeding success and can poison cardinals directly when they consume contaminated insects or seeds.

Habitat fragmentation, while less threatening to adaptable cardinals than to forest-interior species, still impacts some populations. The removal of dense shrub layers in favor of manicured lawns eliminates both nesting habitat and foraging opportunities. Climate change presents uncertain future impacts, though cardinals may benefit in some regions from warming temperatures that extend their range.

Parasitism by Brown-headed Cowbirds poses a reproductive threat. Cowbirds lay eggs in cardinal nests, and the cardinal parents often raise the cowbird chick at the expense of their own offspring. However, cardinals show some ability to recognize and reject cowbird eggs, providing partial protection against this parasitism.

Vehicle collisions claim cardinals when they forage near roadsides or fly low across streets. During winter, cardinals may also face starvation during severe weather events when natural food sources become inaccessible beneath snow and ice, though bird feeders significantly mitigate this threat in many areas.

Reproduction and Life Cycle

Northern Cardinals typically form monogamous pair bonds that often persist across multiple breeding seasons or throughout their lives. Courtship begins in late winter, with males singing persistently to establish territories and attract mates. The male’s mate-feeding behavior, where he offers food to the female, plays a crucial role in courtship and pair bonding, continuing throughout nesting and sometimes year-round.

The breeding season extends from March through September across most of their range, with pairs producing two to three broods annually in favorable conditions. The female selects the nest site, usually in dense shrubs, tangles of vines, or small trees between three and ten feet above the ground, though occasionally nests are built higher or even at ground level.

The female constructs the nest over three to nine days, weaving a cup of twigs, bark strips, grasses, and leaves, then lining it with fine grass and sometimes hair. The male accompanies her during construction but doesn’t assist directly, instead bringing her material occasionally or guarding against intruders.

Females lay three to four eggs per clutch, occasionally as few as two or as many as five. The eggs are white, pale blue, or greenish-white with brown, gray, or purple speckles concentrated toward the larger end. Incubation lasts 11 to 13 days and is performed almost exclusively by the female, though the male brings her food during this period.

Nestlings hatch blind, naked, and helpless. Both parents feed the chicks, initially providing almost exclusively soft-bodied insects. The young develop rapidly, opening their eyes by day four and growing feathers by day seven. Nestlings fledge nine to eleven days after hatching, though they cannot fly proficiently and remain dependent on parental care.

After fledging, young cardinals stay with their parents for 25 to 56 days while learning to forage and avoid predators. The male typically assumes most of the care for fledglings if the female begins another nesting attempt. Juvenile cardinals reach sexual maturity and can breed in their first spring, approximately one year after hatching.

Average lifespan in the wild is approximately three years, with many cardinals succumbing to predation, harsh weather, or disease during their first year. However, individuals that survive to adulthood can live considerably longer, with the oldest recorded wild cardinal documented at 15 years and 9 months. Cardinals in captivity have lived beyond 20 years under optimal conditions.

Population

The Northern Cardinal is currently classified as Least Concern by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), indicating the species faces no immediate extinction risk. This positive status reflects the cardinal’s adaptability, large geographic range, and stable to increasing population trends.

Population estimates place the global Northern Cardinal population at approximately 120 to 140 million individuals, making it one of the most abundant songbirds in North America. The species has experienced a remarkable population increase over the past several decades, with North American Breeding Bird Survey data indicating a cumulative increase of approximately 50% between 1966 and 2019.

This population growth stems from multiple factors. Cardinals have proven exceptionally adaptable to human-modified landscapes, thriving in suburban and urban environments where many other bird species struggle. The widespread popularity of bird feeding has provided supplemental food sources that increase winter survival rates. Additionally, ornamental landscaping with berry-producing shrubs and the suppression of wildfires that once maintained more open habitats have created ideal conditions for cardinal expansion.

The species’ range expansion continues, with cardinals now breeding regularly in southern Canada where they were absent a century ago. This northward movement appears linked to climate warming, increased availability of winter food from bird feeders, and landscape changes that provide suitable habitat.

Despite overall positive trends, some local populations may face pressures from habitat loss or other factors. In parts of the southwestern United States, populations fluctuate with rainfall patterns that affect food availability. However, these local variations occur within the context of range-wide population stability.

Partners in Flight estimates that 79% of the global cardinal population resides in the United States, with additional populations in Canada, Mexico, and Central America. The species’ large population size and positive trends suggest Northern Cardinals will remain common and widespread throughout their range for the foreseeable future.

Conclusion

The Northern Cardinal stands as a testament to nature’s ability to adapt and flourish alongside human civilization. From its spectacular crimson plumage and melodious song to its remarkable intelligence and complex social behaviors, this species continues to captivate observers across the continent. Cardinals demonstrate that conservation success stories need not involve remote wilderness—sometimes the most meaningful connections with wildlife occur in our own backyards. Their expanding range and growing populations suggest that thoughtful landscaping choices, responsible pet ownership, and simple acts like maintaining bird feeders can make genuine differences for wildlife. As we face increasing environmental challenges, the cardinal reminds us that coexistence is possible and that small actions to support biodiversity matter. The next time a flash of red catches your eye on a winter morning, take a moment to appreciate not just the beauty before you, but the resilient spirit and evolutionary success that brilliant bird represents.

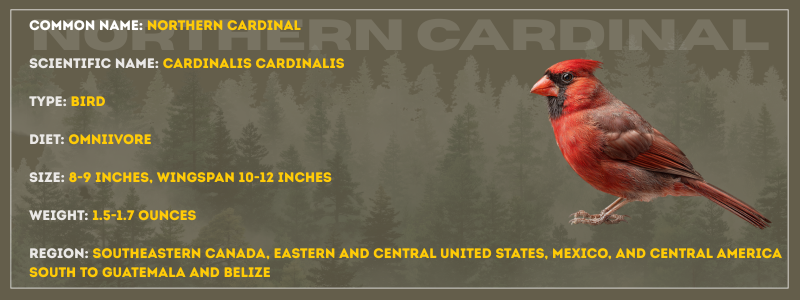

Scientific Name: Cardinalis cardinalis

Diet Type: Omnivore (primarily granivorous with seasonal insectivory)

Size: 8-9 inches in length; 10-12 inch wingspan

Weight: 1.5-1.7 ounces (42-48 grams)

Region Found: Southeastern Canada, eastern and central United States, Mexico, and Central America south to Guatemala and Belize