In the dusky hours when most forest creatures settle for the night, a haunting call echoes through the woodland canopy: “Who cooks for you? Who cooks for you-all?” This distinctive vocalization belongs to one of North America’s most charismatic nocturnal predators—the barred owl. With its soulful dark eyes, cryptic plumage, and remarkable hunting prowess, this medium-sized owl has captivated birdwatchers and nature enthusiasts for generations. More than just another bird of prey, the barred owl represents a fascinating study in adaptability, having dramatically expanded its range over the past century and sparking both ecological concerns and widespread admiration. As human development continues to reshape wild landscapes, understanding this resilient raptor becomes increasingly important for conservation efforts and our appreciation of the complex dynamics within forest ecosystems.

Facts

- Silent Swimmers: Unlike most owls, barred owls will occasionally wade into shallow water to catch fish and crayfish, demonstrating remarkable versatility in their hunting techniques.

- Daytime Activity: While primarily nocturnal, barred owls are more likely than many owl species to be active during daylight hours, especially on overcast days or in dense forests where light is naturally dim.

- Exceptional Hearing: Their facial disc feathers channel sound waves to asymmetrically positioned ears—one higher than the other—allowing them to pinpoint prey location in complete darkness with stunning accuracy.

- Territorial Duets: Mated pairs often perform coordinated vocal duets that can last several minutes, strengthening their pair bond and announcing territorial boundaries to neighboring owls.

- Range Expansion Champions: Over the last 100 years, barred owls have expanded their range westward across Canada and down into the Pacific Northwest, one of the most dramatic range expansions documented in North American birds.

- Long-lived Sentinels: In the wild, barred owls can live up to 18 years, though the oldest recorded individual reached an impressive 24 years in captivity.

- Cavity Nesters Without Construction Skills: Despite requiring large tree cavities for nesting, barred owls cannot excavate their own nest holes and must rely on natural cavities or those created by other animals.

Sounds of the Barred Owl

Species

The barred owl belongs to a taxonomic lineage that places it firmly within the predatory birds:

- Kingdom: Animalia

- Phylum: Chordata

- Class: Aves

- Order: Strigiformes

- Family: Strigidae (true owls)

- Genus: Strix

- Species: Strix varia

Within the genus Strix, the barred owl shares kinship with several other prominent owl species. The spotted owl (Strix occidentalis), found in western North America, is perhaps its most famous relative and has become the center of considerable conservation controversy due to competition with expanding barred owl populations. Other relatives include the tawny owl (Strix aluco) of Europe and Asia, and the Ural owl (Strix uralensis) of northern Eurasia.

Four subspecies of barred owl are generally recognized, though some taxonomists debate their validity. These include the northern barred owl (S. v. varia), the Florida barred owl (S. v. georgica), the Texas barred owl (S. v. helveola), and a poorly defined Central American form. The differences between these subspecies are subtle, primarily involving slight variations in size and plumage coloration that reflect adaptation to regional climates and habitats.

Appearance

The barred owl presents a robust, barrel-shaped silhouette that distinguishes it from the more angular profiles of many raptor species. Adults typically measure 16 to 25 inches in length with a wingspan ranging from 38 to 49 inches, making them considerably smaller than great horned owls but larger than screech owls. Males generally weigh between 1.1 and 1.8 pounds, while females, following the common pattern of reverse sexual dimorphism in raptors, are notably heavier at 1.4 to 2.5 pounds.

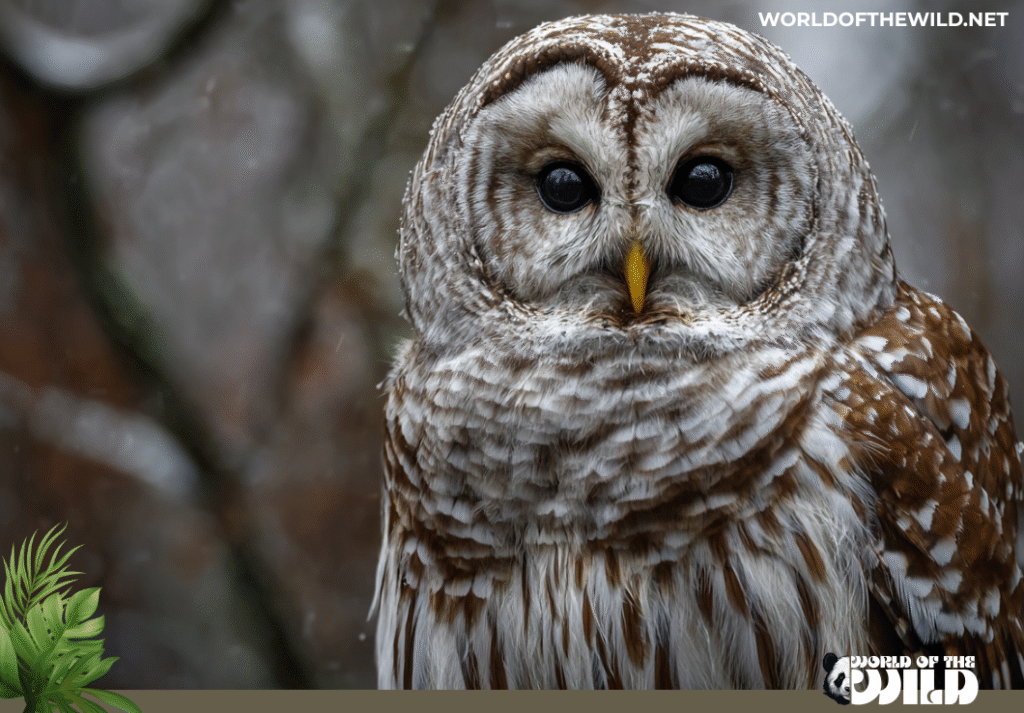

The plumage pattern that gives this owl its common name is striking and unmistakable. The upper breast and throat feature bold horizontal barring in alternating patterns of brown and white, while the lower breast and belly display prominent vertical streaking. This combination creates a distinctive appearance that no other North American owl shares. The back and wings are mottled brown with white spotting, providing excellent camouflage against tree bark.

Perhaps the most arresting feature of the barred owl is its face. Unlike many owl species with piercing yellow eyes, barred owls possess large, liquid-dark eyes that appear almost black, giving them an unexpectedly gentle and soulful expression. These eyes are framed by prominent facial discs—concentric circles of feathers that form a rounded face, helping to direct sound toward the ears. The head is notably round without ear tufts, and the pale yellow-to-ivory beak curves sharply downward, well-suited for tearing prey.

The legs and feet are covered in buff-colored feathers extending to the base of the powerful talons, which are blackish-gray and exceptionally sharp. This feathering provides both warmth and silent approach when swooping down on prey. Overall, the barred owl’s plumage is perfectly adapted for a life spent camouflaged against tree trunks during daylight hours.

Behavior

Barred owls exhibit fascinating behavioral patterns that reflect their role as adaptable forest predators. Primarily crepuscular and nocturnal, they become most active during twilight hours and throughout the night, though they’re far more likely than most owl species to hunt during daylight, particularly on cloudy days or in heavily shaded old-growth forests.

These owls are largely solitary outside the breeding season, with individuals maintaining distinct territories that they defend vigorously against intruders. Territory size varies considerably based on prey availability, ranging from as little as 200 acres in prey-rich environments to over 1,000 acres in less productive habitats. Their territorial defense involves both vocal displays and, occasionally, physical confrontation.

The vocal repertoire of barred owls is remarkably diverse and complex. Their signature call—the aforementioned “who cooks for you” phrase—is just one of at least thirteen distinct vocalizations they produce. These include hoots, barks, cackles, and even screams that can sound disturbingly human-like. During breeding season, mated pairs engage in elaborate duets, with individuals taking turns or calling simultaneously in a behavior that reinforces pair bonds and warns away competing owls.

Hunting strategy demonstrates the barred owl’s opportunistic intelligence. They typically hunt from perches, remaining motionless while scanning the forest floor with exceptional vision and hearing. Upon detecting prey, they swoop down in near-silent flight, their specially adapted feathers muffling the sound of wingbeats. They’re also known to wade into shallow water to capture aquatic prey and have been observed walking along branches to investigate potential food sources—behaviors less common in other owl species.

Socially, barred owls maintain long-term monogamous pair bonds, with couples often remaining together for multiple breeding seasons or even for life. Their intelligence manifests in various ways, including their ability to adapt to human-modified landscapes, problem-solving when accessing food sources, and their varied hunting techniques across different environments.

Evolution

The evolutionary history of the barred owl traces back through the ancient lineage of owls, which first appeared during the Paleocene epoch approximately 60 million years ago. However, the family Strigidae, to which barred owls belong, emerged more recently during the Oligocene epoch around 30 million years ago, diversifying into the numerous species we recognize today.

The genus Strix, which includes the barred owl and its closest relatives, likely originated in the Old World before members dispersed across the Northern Hemisphere. Fossil evidence of Strix species has been found in Miocene deposits from Europe, dating back roughly 20 million years. The separation between Old World Strix species like the tawny owl and New World species like the barred owl occurred relatively recently in evolutionary terms, probably during the Pliocene or early Pleistocene as populations became geographically isolated.

The barred owl’s evolutionary relationship with the spotted owl is particularly intriguing. These species are so closely related that they occasionally hybridize where their ranges overlap in the Pacific Northwest, producing fertile offspring called “sparred owls.” This close relationship suggests a relatively recent evolutionary divergence, likely driven by geographic separation during glacial periods when ice sheets fragmented forest habitats across North America.

Several key evolutionary adaptations have contributed to the barred owl’s success. Their asymmetrical ear placement, a trait shared with many owl species, evolved to provide exceptional sound localization abilities crucial for hunting in darkness. The development of specialized feather structures that enable silent flight represents another critical adaptation, allowing owls to approach prey undetected. The facial disc structure, which functions as a biological parabolic reflector for sound, evolved alongside these auditory specializations.

The barred owl’s relatively generalist ecology—able to exploit diverse prey and habitat types—likely evolved as an advantage in the variable environments of North American forests, where seasonal changes and periodic disturbances would favor adaptable predators over specialists. This evolutionary flexibility has proven especially advantageous in the modern era, enabling their dramatic range expansion and persistence in partially developed landscapes.

Habitat

The barred owl occupies an extensive geographic range across North America, historically concentrated in the eastern United States and southeastern Canada. Their traditional range extends from Florida north through the Atlantic and Gulf Coast states, throughout the eastern deciduous forests, and across the boreal forests of Canada from Nova Scotia west to Saskatchewan. However, the past century has witnessed a remarkable westward expansion, with populations now established throughout British Columbia, Washington, Oregon, northern California, and portions of Idaho and Montana.

This owl shows a strong preference for mature forests with dense canopy cover, particularly those featuring large, old trees that provide suitable nesting cavities. While often associated with swamplands and bottomland hardwood forests in the southeastern United States—where their evocative calls echo through Spanish moss-draped cypresses—barred owls actually inhabit a diverse array of forested environments. These include mixed deciduous-coniferous forests, river valleys, wooded swamps, upland oak forests, and even suburban areas with sufficient tree cover.

Key habitat requirements include a closed or semi-closed canopy that provides daytime roosting cover, an abundance of large trees that may contain natural cavities or support stick nests built by other species, and access to adequate prey populations. Unlike some forest specialists, barred owls can tolerate moderate habitat fragmentation and have successfully adapted to suburban environments, parks, and wooded cemeteries where large trees and prey remain available.

Water features often play an important role in barred owl habitat selection. They frequently inhabit areas near streams, rivers, swamps, or wetlands, where diverse prey communities thrive and where the combination of forest cover and aquatic edge habitat creates ideal hunting conditions. In the western portion of their expanded range, they’ve successfully colonized old-growth coniferous forests previously dominated by spotted owls, demonstrating their ecological flexibility.

Elevation preference varies across their range, though they generally favor lowland and mid-elevation forests below 3,000 feet. In mountainous regions, they typically concentrate in valley bottoms and lower slopes where forest density is greatest.

Diet

The barred owl is a carnivorous generalist, demonstrating remarkable dietary flexibility that has contributed significantly to its success as a species. Unlike specialized predators that depend heavily on specific prey, barred owls opportunistically hunt whatever prey is most abundant and accessible in their territory, adjusting their diet seasonally and geographically.

Small mammals form the core of their diet across most of their range. Voles, mice, shrews, and other rodents constitute the majority of prey items, though these owls also regularly capture larger mammals including rats, squirrels, rabbits, and occasionally even weasels or young skunks. Their hunting efficiency for small mammals is enhanced by their exceptional hearing, which allows them to detect and precisely locate prey moving beneath leaf litter or snow.

Beyond mammals, barred owls consume a surprising diversity of prey types. Birds feature prominently in their diet, ranging from small songbirds to medium-sized species like woodpeckers, jays, and even other owl species including smaller screech owls. Amphibians and reptiles provide important seasonal protein, particularly in southern portions of their range where frogs, salamanders, snakes, and lizards are abundant.

Perhaps most unusually for an owl, barred owls regularly exploit aquatic prey. They’ve been observed wading into shallow water to capture crayfish, small fish, aquatic insects, and even catching frogs and salamanders from pond edges. This aquatic hunting behavior is relatively rare among owls and demonstrates the species’ behavioral adaptability.

Invertebrates, while providing less nutrition per item, supplement the diet—particularly during summer months when insects, spiders, earthworms, and other arthropods become abundant. Large beetles, moths, and crickets are occasionally consumed, especially by younger owls still developing hunting skills.

Their hunting methodology combines patience with explosive action. Barred owls typically hunt from perches 10 to 30 feet above ground, remaining motionless while scanning and listening for prey movement. Upon detection, they drop swiftly and silently, extending their talons at the last moment to strike. Prey is typically killed instantly by the impact and grip of powerful talons before being carried to a feeding perch. Smaller prey items are swallowed whole, while larger animals are torn into manageable pieces using the sharp, hooked beak.

Predators and Threats

Despite their position as skilled predators, barred owls face threats from both natural predators and human-caused factors that can significantly impact local populations.

Natural predation on adult barred owls is relatively uncommon, as few animals are willing or able to tackle a defensive owl armed with sharp talons and aggressive behavior. However, great horned owls—larger, more powerful, and highly aggressive—represent the primary natural predator of barred owls throughout their range. Great horned owls regularly kill and occasionally consume barred owls, particularly when territories overlap or when food becomes scarce. These encounters can significantly influence barred owl distribution patterns, as the smaller species tends to avoid areas where great horned owls are abundant.

Other potential predators include large hawks, particularly red-tailed hawks and northern goshawks, though predation from these species is less common and typically targets juveniles rather than adults. Raccoons, martens, and large snakes may raid nests to consume eggs or young owlets when opportunities arise.

Anthropogenic threats pose more widespread and significant risks to barred owl populations. Vehicle collisions represent a leading cause of mortality, particularly as these owls hunt along forest edges and roadways where rodent populations concentrate. Their low-level hunting flights and tendency to hunt during twilight hours—when human traffic remains heavy—make them especially vulnerable to vehicle strikes.

Habitat loss and degradation continue to threaten barred owls in some regions, though less severely than for more specialized species. Clear-cutting of old-growth forests eliminates essential nesting sites, while the conversion of forests to agricultural land or urban development reduces available hunting territory. However, barred owls’ tolerance for habitat fragmentation and their ability to utilize suburban environments has somewhat mitigated these impacts.

Rodenticide poisoning presents an insidious and growing threat. Barred owls that consume rodents killed by anticoagulant poisons can accumulate lethal doses or suffer sublethal effects that reduce hunting success and reproductive output. This secondary poisoning affects numerous raptor species but particularly impacts owls due to their rodent-heavy diets.

In the Pacific Northwest, an unusual management challenge has emerged: barred owls themselves have become a threat to the endangered spotted owl. The federal government has implemented controversial lethal removal programs to protect spotted owls, placing barred owls in the unusual position of being both a conservation concern in terms of individual welfare and a conservation target in terms of population management.

Climate change may pose long-term threats by altering forest composition, affecting prey populations, and potentially shifting the ranges of both the owls and their primary food sources, though the full impacts remain uncertain.

Reproduction and Life Cycle

The reproductive cycle of barred owls begins with courtship behaviors that intensify during late winter, typically between February and March, though timing varies with latitude. Pair formation or renewal of existing bonds involves elaborate vocal displays, with mated pairs engaging in coordinated hooting duets that can echo through forests for considerable distances. Males also perform courtship feeding, presenting prey items to females as demonstrations of their hunting prowess and ability to provision offspring.

These owls are cavity nesters, requiring large natural hollows in mature trees, abandoned hawk or crow nests, or occasionally human-provided nest boxes. Unlike woodpeckers, they cannot excavate their own cavities and depend entirely on existing structures. Competition for suitable nest sites can be intense, and the availability of appropriate cavities often limits breeding density in otherwise suitable habitat.

The female typically lays two to four white, roughly spherical eggs over the course of several days, usually in March or early April. Egg-laying is staggered, with intervals of two to three days between each egg, resulting in asynchronous hatching and offspring of different ages within the same nest. Incubation duties fall almost exclusively to the female, who remains on the nest for approximately 28 to 33 days while the male provides all food for both his mate and himself.

The owlets emerge covered in white down, blind, and completely dependent on parental care. Their eyes open after about one week, and they develop rapidly on a steady diet of prey delivered by both parents, though the male initially provides all food while the female broods the vulnerable young. By four to five weeks of age, the young owls begin to venture onto branches near the nest in a phase called “branching,” though they cannot yet fly. This is a particularly vulnerable period when young owls may fall to the ground and require parental protection and continued feeding.

True flight capability develops around six weeks of age, though young barred owls remain dependent on their parents for food for several additional months while developing hunting skills. This extended dependency period can last until late summer or early autumn, with family groups gradually dispersing as juveniles gain independence. First-year mortality rates are high, with many young owls failing to survive their first winter due to inexperience, competition with adults for territories, and the challenges of hunting in unfamiliar terrain.

Barred owls reach sexual maturity at approximately two years of age, though some individuals may not breed until their third year, particularly in areas with high population density and limited territories. Once established, pairs often maintain long-term bonds and may occupy the same territory for many years. In the wild, barred owls that survive the vulnerable juvenile period typically live 10 to 18 years, with the oldest known wild individual reaching at least 18 years. Captive birds have exceeded 23 years, suggesting that predation, accidents, and environmental challenges rather than intrinsic aging primarily limit lifespan in natural populations.

Population

The barred owl currently enjoys a conservation status of Least Concern according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature, reflecting stable and in many areas expanding populations across their extensive range. This designation places them among North America’s most secure owl species, contrasting sharply with the conservation challenges facing some of their relatives.

Population estimates suggest approximately 3 million individual barred owls inhabit North America, with the species maintaining healthy densities throughout most of their traditional eastern range. Population trends over recent decades have been predominantly stable to increasing, with the species’ dramatic westward expansion representing one of the most significant range extensions documented for any North American bird species in modern times.

This expansion has occurred without apparent human assistance, driven instead by a combination of factors including natural reforestation following historical logging, the maturation of prairie shelterbelts planted in the early 20th century that created forest corridors across previously treeless regions, and possibly climate changes that have made northern forests more hospitable. The colonization of the Pacific Northwest beginning in the early 1900s and accelerating through the latter half of the century has established substantial populations in regions where barred owls were historically absent.

However, this population success story carries complex implications. In areas where barred owls have expanded into spotted owl habitat, they have become competitively dominant, contributing to declines in the threatened northern spotted owl populations. Barred owls are larger, more aggressive, more adaptable in habitat use, and have broader dietary preferences than spotted owls, giving them significant competitive advantages. They also hybridize with spotted owls on occasion, potentially threatening the genetic integrity of spotted owl populations.

This situation has prompted controversial management responses, including experimental removal programs where wildlife managers lethally remove barred owls from specific areas to protect spotted owl populations. These programs have demonstrated localized benefits for spotted owls but raise ethical questions about killing one native species to protect another and remain subjects of ongoing debate within the conservation community.

Regional population variations do exist. In some parts of their core eastern range, local populations may face pressures from habitat fragmentation and urbanization, though overall population impacts remain minimal. The species’ adaptability and generalist ecology have largely buffered them against the habitat changes that threaten more specialized species.

Conclusion

The barred owl stands as a compelling example of avian adaptability and resilience in an era of rapid environmental change. From their distinctive vocalizations echoing through southern swamps to their controversial expansion into western old-growth forests, these charismatic owls demonstrate both the remarkable flexibility of successful species and the complex conservation challenges of the modern world. Their soulful dark eyes have observed centuries of forest transformation, and their ability to thrive in diverse habitats—from primeval bottomlands to suburban woodlots—speaks to an evolutionary success story written in silent wingbeats and precise predation.

Yet the barred owl’s story also reminds us that conservation rarely involves simple narratives of good and bad. As these owls flourish and expand, their success creates dilemmas for managers struggling to protect their declining spotted owl relatives. This complexity underscores a fundamental truth about ecosystem management: every species exists within intricate webs of relationships, and changes to one thread inevitably affect the entire tapestry.

As we move forward, the barred owl will likely continue its role as both a beloved woodland sentinel and a focal point for discussions about how we balance competing conservation priorities. Whether listening to their haunting calls on a moonlit forest walk or grappling with the ethical implications of their management, we would do well to remember that these magnificent predators are simply living according to their nature—adapting, surviving, and thriving as evolution has equipped them to do. Our responsibility lies not in judging their success, but in ensuring that the forests they inhabit, in all their complexity and biodiversity, continue to echo with the calls of owls for generations to come.

Scientific Name: Strix varia

Diet Type: CarnivoreSize: 16-25 inches (length); 38-49 inches (wingspan)

Weight: Males: 1.1-1.8 lbs; Females: 1.4-2.5 lbs

Region Found: Eastern and central North America, expanding into western North America including Pacific Northwest; ranges from Florida north through eastern Canada, west to British Columbia, Washington, Oregon, and northern California