Few birds possess a silhouette as instantly recognizable as the pelican. With their massive bills, underslung pouches, and pterodactyl-like wingspans, they look like creatures that time forgot—ancient wanderers patrolling the boundary between sea and sky. While often depicted in cartoons as comical gluttons, pelicans are actually highly sophisticated hunters and master aviators.

These birds are significant not just for their unique anatomy, but for their evolutionary staying power. They are supreme adaptors that have thrived on Earth for millions of years, mastering both the air currents and the turbulent waves. Beyond their iconic “smile,” the pelican is a story of biological engineering perfection.

Facts

- The “Bucket” Myth: Contrary to popular belief (and the famous limerick), pelicans do not store food in their pouch for long trips. The pouch is strictly a catching tool; they drain the water and swallow the catch almost immediately.

- Built-in SCUBA Gear: Because pelicans hit the water with force or scoop violently, they have evolved to breathe primarily through their mouth. Their external nostrils (nares) are sealed off to prevent water from rushing into their lungs during a dive.

- A Massive Capacity: The gular pouch of a large pelican can hold up to 3 gallons of water—more than their stomach can hold.

- Totipalmate Feet: Unlike ducks, which have webbing between only three toes, pelicans are “totipalmate,” meaning all four of their toes are connected by a web. This makes them powerful swimmers and aids in incubating eggs.

- Ancient Lineage: Fossil evidence suggests that pelicans have existed in roughly their current form for at least 30 million years.

- Desalination Plants: Like many seabirds, pelicans have special glands near their beak that filter excess salt from their bloodstream, allowing them to drink seawater without becoming dehydrated.

Sounds of the Pelican

Species

Pelicans belong to the Kingdom Animalia, Phylum Chordata, Class Aves, Order Pelecaniformes, and Family Pelecanidae. The single genus is Pelecanus.

There are currently eight recognized living species of pelicans found across the globe:

- Brown Pelican (Pelecanus occidentalis): The only species that strictly dives from the air to catch prey.

- American White Pelican: One of the largest birds in North America.

- Peruvian Pelican: Similar to the Brown Pelican but significantly larger.

- Great White (Rosy) Pelican: Found in parts of Europe, Asia, and Africa.

- Australian Pelican: Boasts the longest beak of any bird in the world.

- Pink-backed Pelican: A smaller species found in Africa.

- Dalmatian Pelican: The largest of all pelican species and one of the heaviest flying birds.

- Spot-billed Pelican: A smaller species native to Southeast Asia.

Appearance

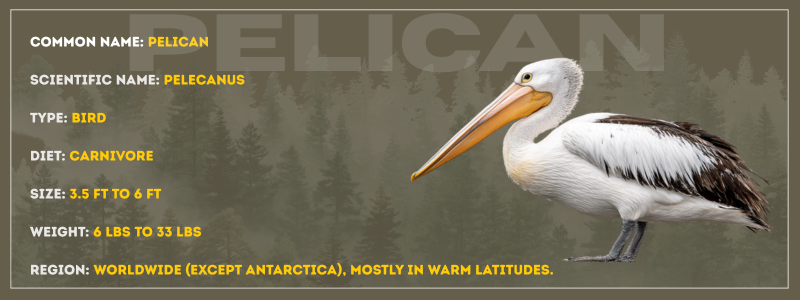

Pelicans are among the largest of all flying birds. They are characterized by a long beak and a large throat pouch used for catching prey and draining water. They have short, strong legs with large, fully webbed feet.

- Size: They range from the smaller Brown Pelican (around 6-10 lbs) to the massive Dalmatian Pelican, which can weigh over 30 lbs.

- Wingspan: Their wings are broad and long, suitable for soaring. The wingspan ranges from roughly 6.5 feet in smaller species to an astounding 11 feet in larger ones.

- Coloration: Most species are predominantly white with black wing tips. The exceptions are the Brown and Peruvian pelicans, which display darker brown and gray plumage. During breeding season, bare patches of skin on the face and pouch can turn vivid colors ranging from orange to red.

Behavior

Pelicans are highly gregarious birds, almost always found in large colonies. They are diurnal (active during the day) and spend much of their time preening to waterproof their feathers using oil from a gland near the tail.

One of their most fascinating behaviors is cooperative hunting. White Pelicans, for example, will form a horseshoe shape on the water, beating their wings and herding fish into shallow water where they can easily be scooped up. This displays a high level of social intelligence.

In the air, they are masters of efficiency. They often fly in V-formations or single lines, surfing the air currents created by the bird in front of them to conserve energy. They are also experts at “dynamic soaring,” using the updraft from ocean waves to glide just inches above the water’s surface.

Evolution

The pelican is an evolutionary success story. The oldest known pelican fossil, found in France, dates back to the Early Oligocene epoch, about 30 million years ago. Surprisingly, this ancient bird’s beak structure is nearly identical to modern pelicans, suggesting that once nature found this successful design, it stuck with it.

They are part of the order Pelecaniformes, which means their closest living relatives include the Shoebill and the Hamerkop, though they also share distant lineage with herons and ibises.

Habitat

Pelicans are found on every continent except Antarctica. They prefer warm regions, though some species migrate to cooler climates during breeding seasons.

Their habitat is strictly aquatic but varies by species. Coastal species, like the Brown Pelican, stick to marine environments, bays, and estuaries. Inland species, like the American White Pelican, prefer large freshwater lakes, marshes, and river deltas. Crucially, they require isolated islands or sandbars for nesting—areas that are safe from land-based predators.

Diet

Pelicans are primarily piscivores (fish-eaters). Their diet consists mostly of schooling fish like sardines, herrings, mullet, and anchovies.

- Foraging Strategy: The Brown Pelican hunts by spotting fish from the air and plunge-diving from heights of up to 60 feet. The impact stuns the fish, which are then scooped up. Most other species feed while swimming, dipping their bills into the water to use the pouch as a net.

- Opportunistic Feeding: While fish make up the bulk of their calories, pelicans are opportunistic. They have been known to eat amphibians, crustaceans, turtles, and, in rare and gruesome instances, smaller birds like pigeons or ducklings.

Predators and Threats

Because of their large size, adult pelicans have few natural predators, though they may occasionally fall victim to large sharks or orcas when on the water.

The young and the eggs, however, are vulnerable. Gulls, skuas, raptors, and corvids will prey on eggs. If nesting grounds are accessible by land, mammals like foxes, skunks, and feral cats can devastate a colony.

Anthropogenic Threats:

- Pesticides: Historically, DDT caused eggshell thinning, nearly wiping out the Brown Pelican.

- Fishing Gear: Entanglement in fishing lines and hooks is a leading cause of injury and death.

- Habitat Loss: The draining of wetlands and development of coastal areas reduces nesting sites.

- Oil Spills: Oil damages the waterproofing of their feathers, leading to hypothermia and drowning.

Reproduction and Life Cycle

Pelicans are colonial nesters, gathering in groups that can number in the thousands. They are generally monogamous for a single breeding season.

- Rituals: Courtship involves visual displays, such as bowing, strutting, and the male presenting nesting materials to the female.

- Offspring: Females typically lay 1 to 3 chalky white eggs. Both parents take turns incubating the eggs by standing on them (using their warm, vascularized webbed feet) for about a month.

- Life Cycle: Chicks are born naked and helpless (altricial). They feed by digging regurgitated food out of their parents’ throats. In ground-nesting species, older chicks form groups called “pods” or “crèches” for protection while parents hunt.

- Lifespan: Pelicans are long-lived birds, typically living 15 to 25 years in the wild, though some have lived much longer in captivity.

Population

The conservation status of pelicans varies by species.

- Success Stories: The Brown Pelican is a major conservation victory; once endangered due to DDT, populations have rebounded, and it is now listed as Least Concern. The American White Pelican is also stable.

- Concerns: The Dalmatian Pelican and Spot-billed Pelican are classified as Near Threatened, with populations declining due to wetland destruction and pollution. The Peruvian Pelican’s numbers fluctuate wildly with El Niño events, which disrupt their food supply.

Conclusion

The pelican is a marvel of evolutionary engineering—a heavy-bodied bird that manages to be a graceful glider and a lethal hunter. From their prehistoric origins to their complex social structures, they represent the resilience of nature. While some species have recovered from the brink of extinction, others remind us of the fragility of our wetlands and coastlines. Protecting the pelican requires maintaining the health of our waters, ensuring that this ancient aviator continues to patrol our skies for millions of years to come.