Across the vast grasslands of North America, a flash of brilliant yellow catches the eye as a stocky bird takes flight, revealing white outer tail feathers like semaphore flags against the prairie sky. This is the western meadowlark, a bird whose flute-like song has become synonymous with the open spaces of the American West. Far more than just another grassland bird, the western meadowlark serves as both a biological indicator of prairie health and a cultural icon—it’s the state bird of six U.S. states, more than any other species. Its ability to thrive in working agricultural landscapes while maintaining wild populations makes it a fascinating study in adaptation, and its complex vocalizations reveal an intelligence that scientists are only beginning to fully understand.

Facts

- Master Ventriloquist: Western meadowlarks can project their songs in ways that make it nearly impossible to pinpoint their exact location, a vocal trick that helps protect them from predators while advertising their territories.

- Agricultural Allies: A single western meadowlark can consume up to 150 grasshoppers in a single day during peak summer months, making them valuable natural pest controllers for farmers and ranchers.

- Vocal Virtuosos: Each male western meadowlark can produce between 8 to 12 different song types, and neighboring males often develop “song neighborhoods” where they share similar vocal patterns.

- Hidden Architects: Their nests are engineering marvels—dome-shaped structures woven into grassland vegetation with a side entrance and often featuring a “runway” of trampled grass leading away from the nest to confuse predators.

- Magnetic Navigation: Research suggests that western meadowlarks, like many migratory birds, can sense Earth’s magnetic field to help orient themselves during seasonal movements.

- Ancient Survivors: Western meadowlarks are remarkably cold-hardy and can survive in areas where winter temperatures drop to -40°F, fluffing their feathers to create insulating air pockets.

- Sibling Recognition: Young meadowlarks can recognize their siblings by voice even after fledging, and will sometimes form loose feeding associations with their brothers and sisters through their first winter.

Sounds of the Western Medowlark

Species

Kingdom: Animalia

Phylum: Chordata

Class: Aves

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Icteridae (blackbirds and allies)

Genus: Sturnella

Species: Sturnella neglecta

The western meadowlark belongs to the New World blackbird family, despite its colorful appearance. The genus Sturnella contains only two species in North America: the western meadowlark and its eastern counterpart, Sturnella magna. These two species are remarkably similar in appearance but dramatically different in song—in fact, they were not recognized as separate species until 1844, when naturalist John James Audubon distinguished them primarily by their vocalizations.

While no officially recognized subspecies of the western meadowlark exist, populations show slight variations in size and coloration across their range, with northern birds tending to be slightly larger than southern populations. The species is closely related to the Chihuahuan meadowlark (Sturnella lilianae) and Pampas meadowlark (Sturnella defilippii) of Central and South America, representing a radiation of grassland specialists throughout the Americas.

The genus name Sturnella derives from the Latin word for starling, while the species name neglecta literally means “overlooked”—a reference to how long this distinctive bird went unrecognized as separate from its eastern relative.

Appearance

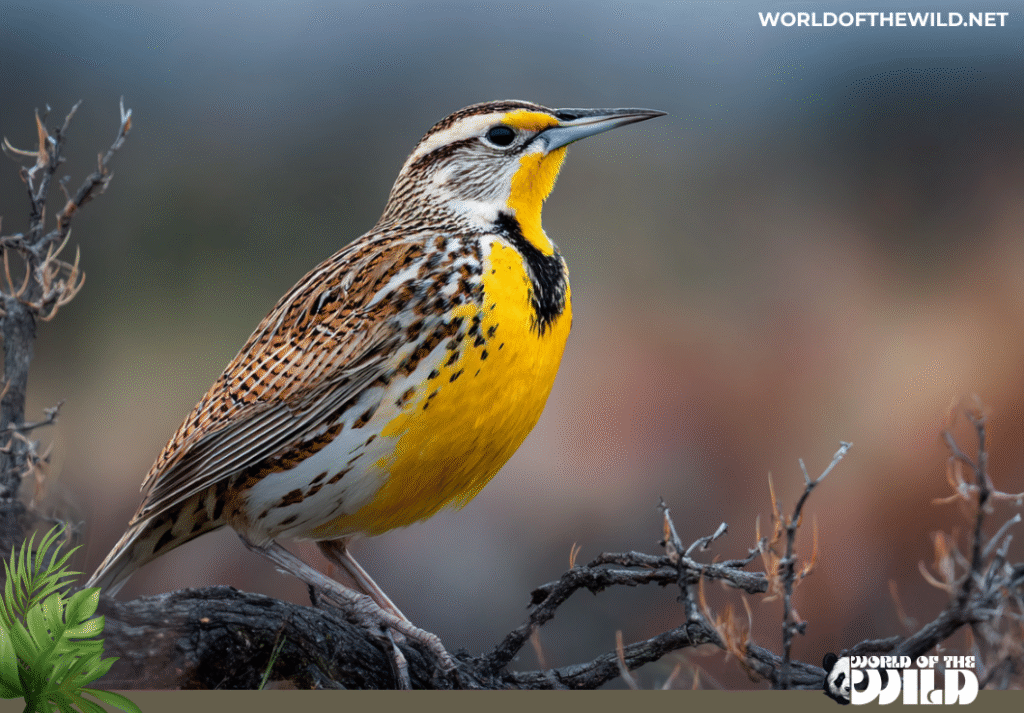

The western meadowlark is a chunky, robin-sized bird measuring 6.5 to 10 inches in length with a wingspan of 13 to 16 inches. Adults typically weigh between 3.1 and 4.1 ounces, with males slightly larger and heavier than females. The bird’s most striking feature is its brilliant lemon-yellow breast and throat adorned with a bold black “V” shaped bib—a marking that looks as though the bird is wearing a distinctive necklace.

The upperparts present a cryptic pattern of brown, buff, and black streaking that provides excellent camouflage when the bird is foraging on the ground. The crown features a light central stripe bordered by dark lateral stripes, and a pale eyebrow stripe (supercilium) adds definition to the face. The bill is long, straight, and sharply pointed—perfectly designed for probing soil and extracting insects.

In flight, the western meadowlark reveals its most diagnostic field mark: bright white outer tail feathers that flash conspicuously against the darker central tail feathers. The flight pattern is distinctive as well, consisting of several rapid, shallow wingbeats followed by brief glides, creating a characteristic fluttering appearance.

During the non-breeding season, the yellow plumage becomes slightly duller, and the black bib may show some pale feather edges, giving it a more mottled appearance. Juvenile birds are paler overall with a less defined breast pattern, though they still show the species’ characteristic body shape and proportions.

The legs are relatively long and pinkish-brown, adapted for walking through grassland vegetation. Sexual dimorphism is subtle, with males showing slightly brighter yellow coloration and a more sharply defined black bib, though individual variation can make sex determination challenging in the field without behavioral cues.

Behavior

Western meadowlarks are primarily ground-dwelling birds that spend most of their time walking through grasslands in search of food, their long legs carrying them deliberately through vegetation. They forage by probing the soil with their sharp bills, using a technique called “gaping”—inserting the closed bill into the ground or under leaf litter and then opening it forcefully to expose hidden prey.

During the breeding season, males become highly territorial, establishing and defending areas ranging from 3 to 15 acres depending on habitat quality. Territorial advertisement is conducted almost entirely through song, with males selecting prominent perches such as fence posts, shrubs, or utility wires to broadcast their melodious, flute-like songs. These vocalizations carry for impressive distances—up to half a mile across open prairie—and consist of rich, whistled phrases that often cascade downward in pitch. The song typically lasts 1 to 2 seconds and has been described as one of the most beautiful bird songs in North America.

Males are polygynous, often maintaining bonds with two or more females simultaneously within their territories. They rarely assist with incubation or chick-rearing, instead focusing their energy on territory defense and attracting additional mates. Communication extends beyond song to include a variety of calls: a low “chuck” note for contact, a rapid chatter when alarmed, and a distinctive rattling call during aggressive encounters.

Western meadowlarks demonstrate sophisticated cognitive abilities, including the capacity for vocal learning and regional dialects. Young males learn songs from adult tutors, and populations in different geographic areas have developed distinctive song variations that function almost like regional accents. Males can recognize their neighbors individually by voice and respond less aggressively to familiar territorial neighbors than to strangers—a phenomenon known as the “dear enemy” effect.

Social behavior varies seasonally. During breeding season, meadowlarks are territorial and aggressive toward conspecifics, but in fall and winter, they often form loose flocks of 10 to 20 individuals that forage together. These winter aggregations provide benefits in predator detection while taking advantage of concentrated food resources.

When threatened, western meadowlarks typically freeze or crouch low in vegetation, relying on their cryptic dorsal plumage for concealment. If pressed, they fly low and direct to nearby cover, rarely flying more than necessary. This reluctance to flush extensively likely evolved as an adaptation to life in open habitats where extended flight increases vulnerability to aerial predators.

Evolution

The western meadowlark’s evolutionary story is intimately tied to the development of grassland ecosystems in North America. The family Icteridae, to which meadowlarks belong, originated in South America approximately 30 million years ago during the Oligocene epoch. These ancestral blackbirds diversified extensively as they spread northward following the formation of the Panamanian land bridge around 3 million years ago.

The genus Sturnella represents a relatively recent evolutionary radiation, with molecular evidence suggesting the split between eastern and western meadowlarks occurred roughly 2.5 million years ago during the Pliocene-Pleistocene boundary. This timing coincides with the expansion of grassland habitats across the Great Plains, driven by increasingly arid climatic conditions and the retreat of forests.

The divergence between eastern and western meadowlarks represents a fascinating example of speciation in closely related birds. Despite their near-identical appearance, the two species have evolved reproductive isolation primarily through vocal differences. When their ranges overlap—which occurs extensively across the central Great Plains—they rarely hybridize, with song serving as the primary barrier to interbreeding. This suggests that sexual selection based on acoustic signals drove their evolutionary divergence.

Fossil evidence of meadowlark-like birds from the Pleistocene has been recovered from tar pits and cave deposits, indicating that the genus successfully weathered multiple glacial cycles. During glacial maxima, grassland habitats contracted and fragmented, likely isolating meadowlark populations and promoting genetic divergence. As glaciers retreated and grasslands expanded, these populations came back into contact, but by then reproductive barriers had solidified.

The western meadowlark’s physical adaptations—including its long legs for terrestrial locomotion, cryptic dorsal coloration, bright ventral warning coloration, and specialized bill for gaping—all evolved in response to selective pressures associated with life in open grassland habitats. The evolution of their complex vocal abilities likely reflects both the acoustic properties of their open habitat, where sound travels far but visual signals are limited, and intense sexual selection by females choosing mates based on song quality.

Recent genetic studies have revealed that western meadowlark populations show relatively low genetic differentiation across their range, suggesting high historical gene flow and recent range expansions. This genetic homogeneity contrasts with their vocal diversity, indicating that song differences arise through cultural transmission rather than genetic divergence.

Habitat

Western meadowlarks occupy one of the largest ranges of any North American songbird, extending from the Great Lakes region west to the Pacific Coast and from southern British Columbia and Alberta south through Mexico to central Oaxaca. Their distribution closely follows the pattern of grassland and open habitats across western North America, though populations have expanded eastward in recent decades as forest clearing has created suitable habitat.

The species shows remarkable habitat flexibility within the constraint of requiring open terrain. Primary habitats include native shortgrass, mixed-grass, and tallgrass prairies, where meadowlarks reach their highest densities. However, they have successfully colonized agricultural landscapes, thriving in hayfields, pastures, and croplands that maintain sufficient grass cover and herbaceous vegetation during the breeding season. The species also occupies desert grasslands, shrubsteppe, sagebrush flats, alpine meadows up to 10,000 feet elevation, and even salt marshes in coastal California and agricultural valleys.

Critical habitat features include a mosaic of grass heights and densities, providing both foraging areas (shorter vegetation) and nesting cover (denser, taller vegetation). Scattered perches such as fence posts, utility wires, shrubs, or rocks are essential for song delivery and territory advertisement. Meadowlarks avoid heavily grazed areas that lack adequate nesting cover but also shun grasslands where vegetation becomes too dense or woody succession has begun to close the canopy.

Winter habitat selection shifts slightly toward areas with lower, sparser vegetation where foraging is easier and energy expenditure is minimized. Some northern populations migrate south for winter, with movements ranging from short distances to over 1,000 miles. However, many western meadowlarks are year-round residents, particularly in milder climates, showing remarkable cold tolerance when food remains accessible.

Habitat quality directly influences population density, with prime territories supporting multiple breeding attempts per season while marginal habitats may see sporadic occupation. The conversion of native prairie to agriculture has produced mixed results for the species—while some agricultural practices create suitable conditions, intensive cultivation, heavy pesticide use, and early mowing of hayfields during nesting season can be detrimental.

Diet

Western meadowlarks are omnivorous ground foragers with a diet that shifts seasonally based on availability. During spring and summer, their diet consists of approximately 75% animal matter, primarily insects and other arthropods. During fall and winter, this ratio reverses, with plant material comprising up to 70% of their intake.

The insect component includes grasshoppers, crickets, beetles (especially ground beetles and weevils), caterpillars, ants, and spiders. Meadowlarks are particularly effective grasshopper predators, and their populations often increase in areas experiencing grasshopper outbreaks. They also consume leafhoppers, true bugs, flies, and occasionally earthworms when conditions allow access to these soil-dwelling invertebrates.

Foraging technique involves methodical walking through vegetation, visually scanning for prey, and probing the ground with their specialized bills. The gaping behavior—inserting the closed bill into soil or debris and then forcing it open—is particularly effective at exposing hidden insects and seeds. This technique requires substantial jaw strength and has driven the evolution of robust skull musculature in meadowlarks.

Plant foods include a wide variety of seeds from grasses, forbs, and agricultural crops. Waste grain from wheat, oats, corn, and other cereal crops provides important winter nutrition. Wild seeds from foxtail grass, bristlegrass, ragweed, sunflowers, and other prairie plants are consumed extensively. During late summer and fall, meadowlarks occasionally eat fruit from shrubs such as elderberry and serviceberry.

Chick-rearing demands protein-rich food, and parent birds provision nestlings almost exclusively with insects, particularly soft-bodied caterpillars and grasshoppers. A single pair of meadowlarks may bring hundreds of insects to nestlings daily during the 11-12 day nestling period.

Water requirements are met primarily through dietary moisture, though meadowlarks will drink from puddles, streams, and other water sources when available. Their ability to derive sufficient water from food allows them to inhabit relatively arid grassland regions.

Predators and Threats

Western meadowlarks face predation pressure from a diverse array of predators targeting different life stages. Ground-nesting habits make them particularly vulnerable during the breeding season. Mammalian predators include coyotes, foxes, badgers, weasels, skunks, raccoons, and ground squirrels, which prey on eggs, nestlings, and occasionally incubating adults. Snakes, particularly bull snakes, gopher snakes, and rat snakes, are significant nest predators across much of the species’ range.

Avian predators include northern harriers, which hunt low over grasslands and can surprise foraging meadowlarks, as well as sharp-shinned hawks, Cooper’s hawks, and American kestrels. Larger raptors such as ferruginous hawks, Swainson’s hawks, and prairie falcons occasionally take meadowlarks. Short-eared owls and barn owls hunt them during twilight hours. Loggerhead shrikes, though small, can successfully capture meadowlarks and impale them on thorns or barbed wire.

Brood parasitism by brown-headed cowbirds represents a significant reproductive threat in some areas. Cowbirds lay eggs in meadowlark nests, and the host parents often successfully rear cowbird chicks, sometimes at the expense of their own offspring. Parasitism rates vary geographically but can exceed 30% in some populations.

Anthropogenic threats have become increasingly significant. Habitat loss through conversion of native grasslands to intensive row-crop agriculture has eliminated vast areas of prime meadowlark habitat. Since European settlement, approximately 70% of North American grasslands have been converted to other uses, representing catastrophic habitat loss for grassland specialists.

Agricultural intensification poses multiple threats: early and frequent mowing of hayfields destroys nests and kills adults; heavy pesticide applications reduce insect prey populations; and the shift from diverse crop rotations to monocultures creates less suitable foraging habitat. Farm equipment causes direct mortality during nesting season, with studies suggesting that mowing operations may destroy 20-60% of nests in managed hayfields.

Collision mortality from vehicles, windows, and power lines kills significant numbers annually. Wind energy development in grassland habitats creates collision risks, though mortality from wind turbines appears lower for meadowlarks than for some other grassland species.

Climate change poses emerging threats through altered precipitation patterns, increased frequency of extreme weather events, and shifts in insect phenology that may create mismatches between peak food availability and nestling development. Drought conditions can reduce reproductive success, while severe storms during nesting season can cause widespread nest failures.

Invasive plant species, particularly introduced grasses such as smooth brome and Kentucky bluegrass, alter habitat structure in ways that may reduce suitability for meadowlarks. These invasive plants often grow taller and denser than native species, potentially impeding foraging efficiency.

Reproduction and Life Cycle

The western meadowlark’s breeding season begins in late April or early May across most of their range, though timing varies with latitude and local conditions. Males arrive on breeding grounds before females, establishing territories through intensive singing from dawn through mid-morning, with a secondary peak in the late afternoon.

Courtship displays are elaborate, with males performing a distinctive “jump flight”—launching several feet into the air while singing, then parachuting back to the ground with tail spread and wings quivering. Males approach receptive females with wings drooped and tail fanned, puffing out their brilliant yellow breast while singing continuously. Females select mates based on multiple criteria, including territory quality, male body condition, and song complexity.

Nest construction is performed entirely by the female and represents remarkable architectural achievement. She selects a site in a depression or natural hollow within dense grass, typically with protective vegetation overhead. Using grasses, stems, and other plant material, she weaves a domed structure with a side entrance, effectively creating a grass-roofed chamber. Many nests include a constructed “runway” or tunnel leading to the entrance, providing concealment from aerial predators. Construction takes 3-6 days of intensive work.

The typical clutch contains 3-7 eggs (most commonly 5), which are white or pale pink heavily spotted and blotched with brown and purple. The female incubates alone for 13-15 days, leaving the nest only briefly to forage. During incubation, her cryptic plumage provides camouflage, and she sits remarkably tight, often not flushing until nearly stepped upon.

Nestlings hatch altricial—blind, naked, and entirely dependent on parental care. Both parents feed the young, though the female provides the majority of care while the male continues territory defense and may court additional females. Chicks grow rapidly on their high-protein insect diet, their eyes opening at 3-4 days and feathers emerging by day 7. They leave the nest at 10-12 days old, before they can fly competently, and hide in surrounding vegetation while parents continue feeding them.

Post-fledging care continues for approximately 3 weeks as young gradually develop full flight capability and foraging skills. Family groups often remain loosely associated through the summer, with juveniles becoming independent by late summer or early fall.

Western meadowlarks are frequently double-brooded and occasionally triple-brooded in southern portions of their range, with second nesting attempts beginning soon after the first brood fledges. The male’s polygynous mating system means successful males may be simultaneously supporting multiple broods with different females.

Sexual maturity is reached at one year of age, with most birds attempting to breed in their first spring. Average lifespan in the wild is 3-5 years, though banded individuals have been documented surviving up to 10 years. Annual adult survival rates average 40-60%, with higher mortality during the first year of life.

Juvenile mortality is substantial, with studies suggesting that only 30-40% of fledglings survive to their first breeding season. This high mortality is offset by the species’ capacity for multiple breeding attempts within a season and the potential for long reproductive lifespans in individuals that successfully navigate their first year.

Population

The western meadowlark is currently classified as Least Concern by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), indicating that the species is not immediately threatened with extinction. However, this designation masks concerning long-term population trends that warrant attention.

The global population is estimated at approximately 40-50 million individuals, making the western meadowlark one of the more abundant grassland birds in North America. However, population monitoring through the North American Breeding Bird Survey reveals troubling declines. Since 1966, western meadowlark populations have decreased by approximately 1-2% annually, resulting in a cumulative decline of roughly 35-40% over the past five decades.

These declines have been most severe in the Great Plains, the species’ core breeding range, where agricultural intensification has been most pronounced. Some regional populations have experienced declines exceeding 50% during this period. Conversely, some peripheral populations, particularly in the Pacific Northwest and intermountain West, have remained relatively stable or shown modest increases.

The species’ wide range and large total population provide some buffer against immediate extinction risk, but the consistent downward trajectory across much of their range has led to concern among conservation biologists. Partners in Flight, a coalition of conservation organizations, classifies the western meadowlark as a “Common Bird in Steep Decline,” placing it on their watch list for species requiring conservation attention.

Population trends vary significantly by habitat type. Meadowlarks using native prairie habitats have declined most steeply, reflecting the ongoing loss and degradation of these ecosystems. Populations in working agricultural landscapes show mixed trends, performing better in landscapes with diverse farming practices, conservation reserve program (CRP) lands, and delayed hay-mowing schedules.

Regional extinctions have occurred in portions of the eastern range where the species was always peripheral, and range contractions have been documented in several areas. However, the species has also demonstrated capacity for colonization, establishing breeding populations in new areas as land-use changes create suitable habitat.

Seasonal population fluctuations are normal, with winter mortality and nest predation creating natural variation. However, the consistent long-term declining trend across multiple decades and throughout most of the species’ range indicates systematic pressures rather than normal population cycling.

Conclusion

The western meadowlark stands as both an icon of the American West and a bellwether for grassland ecosystem health. Its melodious song, striking plumage, and ecological importance as both predator and prey make it a species worthy of celebration and protection. Yet beneath its current status as a common bird lies a troubling narrative of steady decline, driven by the same forces threatening grassland ecosystems throughout North America.

Understanding the western meadowlark’s biology—from its complex vocalizations to its ground-nesting habits, from its role in controlling agricultural pests to its vulnerability to modern farming practices—reveals the intricate connections between this charismatic bird and the landscapes it inhabits. Its story is fundamentally intertwined with the fate of North American grasslands, ecosystems that rank among the most imperiled on the continent.

Conservation of the western meadowlark requires a landscape-level approach that prioritizes grassland preservation, promotes wildlife-friendly agricultural practices, and recognizes that working lands can coexist with biodiversity when managed thoughtfully. Supporting conservation programs that protect native prairie remnants, advocating for delayed mowing schedules in hayfields, reducing pesticide applications, and maintaining diverse crop rotations all contribute to meadowlark conservation.

The next time you hear that cascade of golden notes across an open field, recognize it not just as a beautiful sound but as the voice of the grasslands themselves—a voice that has grown quieter over recent decades and one we cannot afford to lose. The western meadowlark’s persistence through changing times demonstrates resilience, but continued survival will require our commitment to preserving the wide-open spaces where this remarkable bird belongs.

Scientific Name: Sturnella neglecta

Diet Type: Omnivore (primarily insectivorous in summer, granivorous in winter)

Size: 6.5-10 inches (16.5-25.4 cm) in length; wingspan 13-16 inches (33-40.6 cm)

Weight: 3.1-4.1 ounces (89-115 grams)

Region Found: Western North America from southern Canada through Mexico; range extends from Great Lakes west to Pacific Coast